eBook - ePub

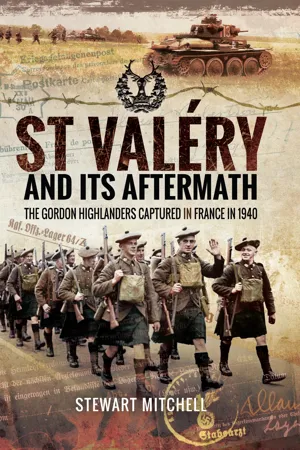

St Valéry and Its Aftermath

The Gordon Highlanders Captured in France in 1940

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This WWII military history chronicles the bravery and daring of Britain's Gordon Highlanders in Nazi occupied France.

During the German offensive of May, 1940, the 51st (Highland) Division—which included the 1st and 5th Battalions Gordon Highlanders—became separated from the British Expeditionary Force. After a heroic stand at St Valery-en-Caux, the Division surrendered when fog thwarted efforts to evacuate them.

Within days, scores of Gordons had escaped and were on the run through Nazi-occupied France. Many reached Britain after harrowing travails, including recapture and imprisonment often in atrocious conditions in France, Spain, or North Africa.

Those imprisoned in Eastern Europe were forced to work in coal and salt mines, quarries, factories and farms. Some died through unsafe conditions or the brutality of their captors. Others escaped, on occasion fighting with distinction alongside Resistance forces. Many had to endure the brutal 1945 winter march away from the advancing Allies before their eventual liberation. This superbly researched book vividly recounts their many inspiring stories.

During the German offensive of May, 1940, the 51st (Highland) Division—which included the 1st and 5th Battalions Gordon Highlanders—became separated from the British Expeditionary Force. After a heroic stand at St Valery-en-Caux, the Division surrendered when fog thwarted efforts to evacuate them.

Within days, scores of Gordons had escaped and were on the run through Nazi-occupied France. Many reached Britain after harrowing travails, including recapture and imprisonment often in atrocious conditions in France, Spain, or North Africa.

Those imprisoned in Eastern Europe were forced to work in coal and salt mines, quarries, factories and farms. Some died through unsafe conditions or the brutality of their captors. Others escaped, on occasion fighting with distinction alongside Resistance forces. Many had to endure the brutal 1945 winter march away from the advancing Allies before their eventual liberation. This superbly researched book vividly recounts their many inspiring stories.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access St Valéry and Its Aftermath by Stewart Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781473886605Subtopic

Modern British HistoryChapter 1

Hoping for the Best – Planning for the Worst

The Gordon Highlanders, like most infantry regiments of the British Army, operated an integrated three part organizational arrangement. These comprised a Regimental HQ or ‘Depot’ (Aberdeen, in the case of the Gordon Highlanders) and two Regular battalions (staffed by full-time, career, soldiers), each of a nominal strength of thirty officers and 930 other ranks, together with some twenty attached specialist trades from other Corps, e.g. the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) and the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC). In addition there were the Territorial Army battalions (TA) for part-time soldiers and the Gordon Highlanders had the 4th (Aberdeen City) Battalion, the 5th/7th (5th Buchan & Formartine merged with the 7th Deeside) Battalion, the 6th (Banff & Donside) Battalion. At any particular time, only one Regular Battalion (1st or 2nd) would serve at ‘home’ (i.e. somewhere in the UK) while the other was overseas (i.e. somewhere in the British Empire). However, at the end of 1934 neither of these battalions was actually in the UK. The 2nd Battalion had been posted to Gibraltar in October 1934. The 1st were in the throes of returning home, bound for Redford Barracks, Edinburgh, returning from fifteen years’ continuous overseas service, in Turkey (March 1920); Malta (November 1921); India (1925) and Palestine (1934).

However, an extraordinary opportunity was afforded by the positions of the 1st and 2nd Battalions at the beginning of 1935. As the 1st Battalion sailed home from Palestine they were allowed to make a special call at Gibraltar to meet up with their ‘brethren’ of the 2nd Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Burney. The previous meeting of the two battalions in peacetime took place in 1898 in India. General Sir Ian Hamilton, the Colonel of the Regiment, travelled out especially to take part in this event. (The Colonel of the Regiment is an honorary ceremonial position and not to be confused with the military rank of colonel. This title is generally conferred on retired senior officers who have a close link to the regiment. In both these respects Sir Ian was undoubtedly qualified.) The two battalions paraded together, creating a magnificent spectacle enjoyed by dignitaries, the soldiers and the public. An inspection was carried out by the Governor, General Sir Charles Harrington GCB GBE DSO.

In September 1935 the long-awaited move of the ‘home of the Regiment’, the Regimental Training Depot and HQ, at Castlehill Barracks, took place with the opening of the new barracks at the Bridge of Don. The ceremony was presided over by the 11th Marquis of Huntly (The Duke of Gordon) whose ancestor, the 5th Duke, had raised the Gordon Highlanders in 1794 and whose tartan was adopted by the Regiment. There were many other dignitaries present, including the Marquis of Aberdeen and the Colonel of the Regiment, eighty-two-year-old General Sir Ian Hamilton. Sir Ian had led the parade, which marched from Castlehill to the new Gordon Barracks, cheered all the way by crowds lining the streets. These new barracks were spacious and modern and situated at the northern edge of the city.

As the bells rang in the New Year of 1938 they were also signalling the ringing of changes for the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders. The year started routinely enough but no one could predict this was in reality the year that began the countdown towards another war in Europe. The Battalion’s activities in Edinburgh included many ceremonial duties, such as the changing of the Castle Guard on Edinburgh Castle’s Esplanade, while the band had played at the Scotland versus Wales rugby international at Murrayfield. Ceremonial duties apart, much of their time had also been taken up with the move to modernize and mechanize the British Army, which involved a great deal of training with the new Bren guns and anti-tank rifles.

The TA also moved into the mechanized era. In June 1938 the 5th/7th Battalion decided their annual camp and route march through Aberdeenshire should be mechanized. Their first leg was from Ellon to Haddo, the seat of the Marquis of Aberdeen, which involved an eight-mile march, with the trucks being loaded as if for active service. Along the way their progress was interrupted by the RAF dropping flour bombs to simulate an air attack, with several direct hits being scored. From Haddo the Battalion was fully mechanized with over fifty vehicles involved, including thirty trucks, twelve buses and ten cars. Over the next three days they covered sixty miles to Ballater, during which crowds cheered their progress as the men debussed to march through the various towns and larger villages en route. This increased the morale of the soldiers, appealed to the patriotic sprit of the public and possibly encouraged other young men in that community to enlist. As a further feather in their caps, the Battalion was awarded the Freedom of the Burgh of Banchory. A ceremony to mark this was held on 25 June 1938, when the whole Battalion formed up in the town square. The honour was conferred on the Battalion by the Provost, James M. Burnett, presenting a scroll in a silver cylinder, engraved with the Banchory coat of arms and the Regimental crest, to the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Alick Buchanan-Smith OBE TD. In exercising their new right, the Battalion marched through the town with bayonets fixed.

The weather was particularly inclement for June, with torrential rain making life uncomfortable for the men spending so much time marching or under canvas. The whole camp and manoeuvres lasted for a fortnight and a BBC Outside Broadcast Unit followed their progress. This was originally planned as a trial, not for transmission, but the producer considered the results were so good that the material was broadcast to the nation. Among their adventures was a night exercise which involved the erection of a bridge over the River Dee, with the assistance of the Royal Engineers of 51st (Highland) Division. The rain had swollen the river so that the strong current proved a challenge and threatened the success of the operation. After an arduous forty-eight hours without sleep, they were successfully across the river but still had some way to march, in the torrential rain, to reach their camp. Meanwhile, the drummers and pipers were more fortunate and had gone directly to the encampment and pitched their own tents. The Quartermaster, Bill Craig, was the hero of the hour when, considering the weather conditions, he ordered that tents be pitched for the whole Battalion. On their arrival the remainder of the Battalion were relieved and delighted at the sight that greeted them as they had not looked forward to the prospect of pitching their own tents in sodden ground before they could rest. Once a meal had been served and a tot of rum issued most were asleep instantly.

Refreshed, the plan for the next day was for a march over the Cairn o’ Mount to Laurencekirk. (The Cairn o’ Mount is a 454-metre-high mountain pass through the Grampian Mountains which has served as a military route since Roman times.) The Commanding Officer (CO) considered that the continuing foul weather made this exercise inadvisable but, at the suggestion of some of his officers, the men were given the option to volunteer for this or travel by mechanized transport. To the CO’s pleasant surprise, all but fifteen men volunteered. Overall the annual camp and route march was considered an achievement of logistics and endurance which was accomplished successfully in extremely difficult conditions. The CO was justifiably proud of his men’s achievements, whilst they knew it was an experience they were glad to have done but that none would easily forget.

For the 1st Battalion, the news was of their new posting to Talavera Barracks, Aldershot, Hampshire. This was greeted with mixed feelings. Some referred to Aldershot as the ‘sunny south’ whereas others were sorry to leave Auld Reekie, as Edinburgh is known. The 1st Battalion’s correspondent to the Regimental magazine, The Tiger & Sphinx, wrote of sorrow at leaving the many good friends made in Scotland’s capital and now having to turn their attention to ‘the grim reality of Aldershot’. This posting was for four years and at this time there was no suggestion that this would not be the case. January 1938 not only brought news of their posting south but also that of a new Commanding Officer. Lieutenant Colonel J.M. Hamilton DSO had completed his tenure of the post and was succeeded by Lieutenant Colonel C.M. Usher obe. Usher was an eminent sportsman in his own right, having played rugby at international level sixteen times, captaining Scotland in 1920 and 1921 while serving as a young lieutenant of the Gordons.

Another character of the 1st Battalion came to the public’s attention in the United States of America when, in January 1938, the Washington Post printed a front-page article featuring ‘Champ’ the 1st Battalion’s mascot. The men blushed to hear their dog, which they all held in great affection, described as ‘the mascot of one of the world’s most famous outfits of fighting men’. Champ adopted the Regiment, rather than the usual alternative arrangement, when the 1st Battalion’s Military and Pipe bands were on a tour of South Africa as part of the 1936 Empire Exhibition. Champ, a handsome brown dog, attached himself to the pipe band at Braamfontein Barracks, Johannesburg, in the first week of their tour and just refused to go away. He was a quick learner and knew the roll of the drums preceded the playing of the National Anthem. On hearing the drums roll he would march on to the bandstand and stand at attention on his haunches. On parades, Champ led the pipers and barked at people who got in the way. According to the Bandmaster, William Norris Campbell LARM ARCM, Champ had an ear for music, liked the sound of the bagpipes and was the only South African in the Gordon Highlanders. At the end of the four-month tour, Lieutenant Stuart cabled the British Board of Agriculture and Fisheries for permission to take Champ back to Scotland and this was approved, subject to the usual quarantine arrangements. At their final concert in Johannesburg, the city’s Caledonian Society presented Champ with a collar and a first-class ticket to Edinburgh. After his quarantine in Southampton, he re-joined the Regiment in Edinburgh and settled down quickly, appearing not to miss the sunshine of his former homeland. He was a particular favourite with the boy soldiers and they were pictured with him and his handler, Private Arthur Smith, in the Tiger & Sphinx in 1938.

When the 1st Battalion arrived in Aldershot on 16 March 1938 they immediately made an impression. They paraded through the town, en route to their barracks, led by the Pipes and Drums of the 1st Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. They didn’t have very long to settle in when they were involved with the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Aldershot on 12 April, which included the Gordons demonstrating an infantry and tank attack. In June they took part in the tremendous spectacle of the world famous Aldershot Searchlight Tattoo which included two more royal visitors in the shape of the young Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, who came to the children’s daytime rehearsal. Towards the end of the year they were also involved in a review of mechanized troops by King Carol of Rumania and the Gordons were able to show off an entire company of mechanized infantry accompanied by a Bren-gun carrier platoon drawn up in battle order.

Undoubtedly, the most disturbing aspect of 1938 was the Czechoslovakian Crisis. The Sudetenland, areas of Czechoslovakia where the inhabitants were mostly German speaking, became a focus for Hitler’s expansionist ambitions in February 1938. This prompted a crisis in Britain and France as the formation of Czechoslovakia had been part of the settlement after the Great War and for a time tensions were running high. Reinforcements, in the form of a draft of newly-trained men, were sent to Aldershot from the Depot in Aberdeen. They were given a great send off from friends and families. A photograph of this event featured in the local newspaper showing them waving their Glengarry bonnets from the train with the caption ‘A Cheery farewell from Depot Gordon Highlanders who left from Aberdeen Station for Aldershot where they will join the 1st Battalion which is going to Czechoslovakia’. On the outside of the carriages the men had written in chalk various satirical and patriotic slogans such as ‘To heil with Hitler’. Among this group was George Clyne who, like many others, had only recently completed his basic training.

The 1930s was a tumultuous decade for Europe and there was some disquiet about what the next turn of events would mean for the country. The 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders were at one point on six hours’ notice of mobilization to be sent to central Europe, with one draft already embarked at Southampton, only to be recalled the next day. This immediate crisis was avoided following the ‘Munich Agreement’ between the German Chancellor, Adolf Hitler, and the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain. Despite the latter’s claims of the agreement bringing ‘peace for our time’ this has since been widely regarded as an act of appeasement but Britain was not ready for another war.

The Czechoslovakian crisis did, however, serve as a wake-up call to the government. As a consequence it was recognized that the British Army was too small to counter the rising military strength of Hitler’s Germany and a serious effort was undertaken to expand the Army, including doubling the size of the Territorial Army. Britain was in a state of economic depression in the 1930s and in the rural area of the North-East of Scotland a large proportion of the population were working in agriculture, where traditionally incomes were very low. The Territorial Army was a popular pastime in these austere times, where men would meet and socialize in the local drill hall. They were also enticed by the small bounty payable and the attraction of the two-week annual camp, which was not only as good as a holiday they could not otherwise afford, but they also received the same pay as a Regular soldier for the duration of the camp. Harry Tobin enlisted into the 5th/7th Battalion (TA) Gordon Highlanders in 1937, shortly after his 17th birthday. He was persuaded to join up by Captain Bill Lawrie, whose civilian occupation was as the physical education teacher at Bucksburn Intermediate School. Bucksburn, situated on the western outskirts of Aberdeen, was home to the Battalion’s Headquarters. HQ Company included many local men who were workers at the nearby Stoneywood and Mugiemoss paper mills. In 1938 their summer camp was near Drumlithie, south of Stonehaven in the Howe o’ the Mearns. While in the TA Harry learned to drive in an army truck, helped on by his cousin, also Harry Tobin, who was the Battalion Transport Sergeant. Harry found his new skill very useful as he found a civilian job as a driver.

For the Gordon Highlanders the Army expansion resulted in a large number of recruits into all their TA Battalions. For example the 4th Battalion reported they were at full establishment while the 5th/7th had a surplus. Historically the 7th Battalion had drawn recruits from the Shetland Islands, but no effort had been made to include the islands since the end of the Great War. When the assistant adjutant visited Shetland in the spring of 1939 he recruited over 100 men in a very short time. The expansion meant the formation of new units, for example the 5th/7th Battalion Gordon Highlanders was, on the eve of the Second World War, split and its two First World War components restored. The 5th Battalion’s area was Buchan and Formartine, while the 7th Battalion covered Kincardine, Deeside and the Shetland Isles. Lieutenant Colonel Alick Buchanan-Smith, who had commanded the 5th/7th Battalion, commanded the 5th while Lieutenant Colonel J.N. Reid took over temporary command of the 7th.

In view of the deteriorating international situation and the rise of Nazi Germany, with the increasingly belligerent approach of Adolf Hitler, Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, persuaded the cabinet of Neville Chamberlain’s government to introduce a limited form of conscription. As a result, Parliament passed the Military Training Act on 26 May 1939. This Act applied to males aged 20 and 21 years old who were to be called up for six months’ full-time military training and then to be transferred to the Reserves. This was the UK’s first act of peacetime conscription and was intended to be temporary in nature. Men called up were to be known as ‘militiamen’ to distinguish them from the Regular army. To emphasize this distinction, each man was issued with a suit in addition to a uniform. There was one registration date under the Act, on Saturday, 3 June 1939. Understandably, but significantly, registration under this Act was not required for men who had already enlisted into the Territorial Army, which in some minds was an incentive to join the part-time TA rather than spend a compulsory six months in the army fulltime. Charles Morrison, from Aberlour on Speyside, turned 20 years old in April 1939 but was unaware of the requirement of this legislation and the implications for him. However, by chance, at seven o’clock one evening, he heard a radio announcement about the imminent implementation of the new legislation. The BBC accent on the crackling radio also went on to inform him that those who had enlisted into any Territorial Volunteer unit by midnight that same evening, only five hours later, were exempt from the conscription. Charles, a shoe salesman, had no military ambitions and did not relish the prospect of a full-time posting into the army when the less onerous, in his opinion, requirements of the TA were the alternative. Unfortunately for Charles, normal business hours were over for the day but he was determined to try and sign up before the midnight deadline. There was one small glimmer of hope as he sought the help of the local recruiting officer, Sergeant Geddes. He told Charles there was a TA dance taking place that night in Dufftown, Banffshire, and that the duty officer would have the authority to sign his enlistment form. With Sergeant Geddes in tow he made the seven-mile dash to Dufftown, like Cinderella, with a midnight deadline but hurrying to arrive rather than depart by the witching hour.

On arrival at the dance venue he was introduced to Captain Spence, the duty officer. To Charles’s surprise Captain Spence mentioned they had met before but Charles couldn’t recall what this occasion had been. Then it dawned. The previous year he had played against this officer in a competition at Dufftown Golf Course, a match which Charles had narrowly won. Anxiously, he wondered if his journey had been in vain. Would Captain Spence secure his revenge by not co-operating in his scheme? However, there was only one hiccup in the process. A list of questions on the enlistment form was read out for Charles to answer. His embarrassment came when Captain Spence passed the form to a young lady present to ask one final question. This was ‘are you in the habit of wetting the bed?’, whereupon the assembled company collapsed in laughter, drowning out his reply. Captain Spence, having exacted his revenge, duly signed the form. Charles was relieved as he had narrowly avoided conscription, becoming 2881803 Private Morrison, C., and the newest recruit into the Territorial Army, 6th Battalion Gordon Highlanders.

In the spring and summer of 1939 everyone was still hoping and convincing themselves there would be no war. This was not the case however, at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Raonuill (Gaelic for Ranald, but he was affectionately known as Ran) Ogilvie was undergoing his officer training where he and his fellow...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Hoping for the Best – Planning for the Worst

- Chapter 2 The Battle for France

- Chapter 3 The Long Weary Trail to the East

- Chapter 4 Stalagites – Life in the PoW Camps

- Chapter 5 Gambling Everything – Escape or Death

- Chapter 6 A Bitter Winter

- Chapter 7 Homeward Bound

- Chapter 8 Epilogue

- Appendix: Gordon Highlanders Captured or Killed In France in 1940

- Plate section