eBook - ePub

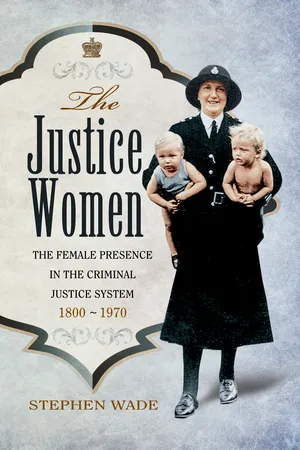

The Justice Women

The Female Presence in the Criminal Justice System 1800-1970

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The first policewomen were established during the Great War, but with no powers of arrest; the first women lawyers did not practise until the early twentieth century, and despite the fact that women worked as matrons in Victorian prisons, there were few professional women working as prison officers until the 1920s. The Justice Women traces the social history of the women working in courts, prisons and police forces up to the 1970s. Their history includes the stories of the first barristers, but also the less well-known figures such as women working in probation and in law courts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Charity, Education and Good Works

I am quite agreeable that a woman shall be informed about everything, but I cannot allow her the shocking passion of acquiring learning in order to be learned.

Molière, Les Femmes Savantes

Important historical change begins with the book and leads to anger in the streets. That common view of history might be challenged, but in the case of women’s right to an education and to a profession, it has a strong element of truth.

On 18 February 1918, Marie Belloc Lowndes, sister of the writer Hilaire Belloc, sat with her friends and enjoyed a discussion on politics. She was sitting in The Thirty Club, around the corner from Grosvenor Square in London, and she wrote in her diary: ‘I sat between Lady Stanley and Fanny Prothero.… There was a good deal of talk about the effect of war on human beings. Marie de Rothschild told us that she had heard the Germans had a hundred submarines.’

There are many remarkable aspects to note about that chat. First, the club was (and is) exclusively for women, and was originally intended for women in the advertising industry; second, the women were talking about a traditionally male preserve (men would talk of submarines after dinner when they had adjourned to a separate room for brandy and cigars), and also that aristocrats and commoners were talking at their leisure. All these points indicate a new world in terms of many feminist ideals and aims.

The talk they had was on current topics, issues of the day. The women in Marie’s circle were intelligent, free-thinking, politically committed; if we ask what had created this intellectual milieu, the answer lies partly in the notion of service. Beatrice Webb, in her autobiography, suggests that from the late Victorian period there was transference of the ideals of shared beliefs into a more dominant notion of service. In other words, there was a new sense that serving ‘man’ – working for the personal and social betterment of fellow creatures, was taking over from merely God-centred active Christianity.

A century earlier, with the Evangelical movement – the crusades of Methodism and Quakerism to help and serve the ‘underclass’ of the labouring classes spawned by the Industrial Revolution and the great demographic shifts in population settlement – charity permeated everywhere. The millions of publications of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge established the place of reading and education at the centre of both charity and reform. When science also experienced a kind of revolution after Darwin and others had challenged the body of knowledge within scripture, in a sense, man began to take the focal position of interest and enquiry. Beatrice Webb saw that service was engendered in the midst of all this, so when women began to enter higher education, and the fight for degree qualifications and entry to the professions escalated, there was already a habit of mind that would relate to careers within the law.

A typical example of this is the work involved in the Women’s Industrial Council in the years from 1889 to 1914. In 1889 the Women’s Trade Union Association (WTUA) was founded ‘to establish self-managed and self-supporting trade unions’, and then, obviously, along with such ideals came the tasks associated with helping and advising women at work in industry. The first report of the WTUA covered trades such as those of the tailoress, mantle maker, shirt maker and umbrella maker. Not only was practical advice given to members, but also a course of lectures, and these lecture topics tell us clearly that there was, as part of the Union work, a fair amount of legal knowledge. For instance, the following topics were included in the lectures given to working women: The Labour Laws of Australasia, The Minimum Wage, separate courts of justice for children, Prison Reform and The Employment of Children Act.

In the whole range of social and political activities in this age of the fight for female suffrage and for workers’ rights, knowledge of the law was increasingly important, and women were aware of the fact. This may be seen in the ranks of the Actresses’ Franchise League also. It was formed in 1908 with the aim of staging propaganda plays and giving lectures and in its ranks were products of the new liberal thinkers, some of them graduates. Beatrice Harraden, for instance, gained a BA degree with honours in classics and maths at Bedford College, and Violet Hunt, one of the founders of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, was another member. Inevitably, these women would learn a great deal about law and administration. This political education provided a foundation for the future openings in the careers forming the justice system. In fact, Rose Lamartine Yates, a graduate of Royal Holloway College, married a lawyer, Tom Yates, and as Irene Cockcroft has written, ‘She studied law with Tom in order to help him with his law practice. In doing so she became aware of the inequity in law between men and women.’

If we shift focus to the dominant ideology of the Victorian age, back to Patmore’s poem and its thinking, the stress in virtually all discourse on education is that a woman is basically a different being from a man – one shaped and destined for the home and for mere decoration rather than any social use beyond the walls of the house. A strong expression of this is the denigration of them in much imaginative writing, stressing their almost anarchic dynamic in society. In Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, for instance, there is this:

It is queer how out of touch with truth women are. They live in a world of their own, and there has never been anything like it, and never can be. It is too beautiful altogether, and if they were to set it up it would go to pieces before the first sunset. Some confounded fact we men have been living contentedly with ever since the day of creation would start up and knock the whole thing over.

Conrad’s very gendered prose reaches out to appeal to that construct of the age, the male-fashioned Empire. The male ideology – as Conrad’s novel investigates – created war and conquest. Women freethinkers of the nineteenth century challenged the male politics of power, and they saw education, of a very different hue to that given in crammers and public schools, as the force for liberation and reviving, innovative change.

The press saw any educational achievement by women as something miraculous, and it made good copy, as in this report from 1887:

A WOMAN STUDENT’S SUCCESS

The Great Classical Tripos which was published at Cambridge on Saturday was remarkable for the success obtained by a Girton student. The lady, Miss Ramsay, beat all the male students, she being the only one of either sex to pass in the first division.… Miss Ramsay’s father, Sir James Ramsay, was distinguished at Oxford, where he took a double first. The present Professor of Latin in the University of Glasgow is her uncle.

The modern reader might see this is a wonderful instance of DNA expressing itself in the genes of the woman scholar, but in the 1880s it was worth some column space in ‘The Thunderer’ (The Times).

The early initiatives that aimed at ringing the changes on women’s education were always happening in a context of charitable work. Women, notably from the Regency years onwards, being frustrated in the main spheres of professional work, expressed themselves in ‘good works’. The evangelical movement of the early nineteenth century stressed service to God and man, and work for the betterment of society as a whole. Prison visiting was the most obvious pathway to this fulfilment. Women visited prisons, workhouses and areas of poverty, hoping to learn and to understand what changes were needed.

There was a more common and general outlet for such social work too. This was in the management of the workhouses, which had sprung up across the land after the Poor Law legislation of the 1830s. By the last quarter of the century, women were involved in the work of the boards of workhouse guardians, across the land. Naturally, this work seemed to many to be no more than an extension of their status as ‘angels in the house’ as they were still working in a ‘home’. But it is clear, notably from research done by Patricia Hollis, that the women guardians were doing very much what prison workers had to do, in all but name: ‘“Women nosed around (often literally so) those sanitary facilities and parts of the hospitals and workhouses which the gentlemen very rarely visit,” said Miss Thorburn of Liverpool.’ Hollis describes the ‘hands-on’ management of these women: ‘As they visited the wards, they prodded the beds, had the mattresses picked over to remove the lumps, and changed the linen. Mrs Despard and Mrs Pankhurst were just two of many who threw out the hard forms on which the elderly sat … and replaced them with comfortable Windsor chairs.’

A typical example of the woman manager in the provinces was a Mrs Buckton, in Leeds, where a school board had been set up in 1870. Hollis sums up: ‘Her credentials established in womanly work, she was soon contributing to the full field of educational policy.… She felt that it was impossible for widows, deserted wives, fathers disabled by accident or disease to pay the school fees when the children were starving or halfclad.’ What could be a better apprenticeship, speaking generally of all such women who aspired to do professional work, than to run a school or workhouse board? It was surely one of the contributing factors to the steady advance of the woman professional in the justice system itself.

There were also, with prison in mind as well as Poor Law provision, the lady visitors. These were the forerunners of today’s Independent Monitoring Board, whose members visit prisons to check on conditions, talk to inmates about conditions and treatment, and report back to the governor. In the nineteenth century, it was easier for a lay person to visit a prison, as memoirs show. Often, the visitors were independent travellers who had charitable purposes and wanted to produce documentary accounts of prison life.

Flora Tristan, a French traveller, was given access as a lay visitor to Coldbath Fields Prison, Newgate, St Giles rookery, and Bethlem Hospital. In her summing-up of the situation of English women, she wrote, ‘English women lead the most arid, monotonous and unhappy existences imaginable.… As young girls they are brought up according to the social position of their parents, but whatever rank they must occupy in life, their education is always influenced to a greater or lesser degree by the same prejudices.’

By the last years of Victoria’s reign, there had been established a Lady Visitors’ Association for prison visits, and, as the National Association of Prison Visitors notes, this organization was made official by 1922, forming the precursor of the Independent Monitoring Board of today. By 1944, two single-sex groups for visiting had been made, and then that amalgamated to become The National Association of Prison Visitors.

Between the first prison work of Elisabeth Fry and the first prison visitors, and the new breed of prison wardresses we can detect from the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the move from simple charity to the first hints of a regulated profession was remarkable progress. In the last years of the century, the whole subject of penology was much more prominent internationally as well as nationally. The first prison congresses were held, and there was an increase in social commentary and documentary related to the experience, structure and criticisms of the prison estate. The fact that the thinking behind prison establishment had always been military in hue led to all kinds of perceived shortcomings, and this in turn led to changes. One of the most notable advances was the realization that women should be housed in prisons separate from the men. In the first ten years of the twentieth-century, a number of prisons had their female offenders transferred, as for instance in Lincoln, whose female convicts were moved to Nottingham in 1903.

One of the most informative documents pertaining to the prison visiting of women charity workers is the book Prisons in Scotland and the North of England, written by Elizabeth Fry and her brother John Gurney. It was published in 1819, at the time when Robert Peel was in the middle of his jail reform legislation, working to improve the lamentable conditions of local jails as first reported on by John Howard in 1777.

In this account of Fry’s work we have detailed reports on jails and bridewells, and very few impressed Miss Fry. There is a noted absence of any female staff, but in one jail, at Preston, the enlightened governor used a monitress system to oversee work by women. The most telling insight in the book is Fry’s experience at Liverpool:

During our stay at Liverpool the magistrates kindly permitted us to form a Committee of Ladies, who are now engaged in visiting and superintending the numerous females in this large prison. It was highly interesting to observe how much these unhappy women rejoiced in the prospect of being thus watched and protected.

In Fry’s report, when she puts together her general observations, the subject of female staff is made a special issue:

Women prisoners are generally very fearfully exposed to the male servants of the prisons in which they are confined. Such servants are necessarily very frequently in their company, and may sometimes be tempted to apply these opportunities of communication to corrupt and dangerous purposes. From the probability of all such contamination these women ought to be protected by being placed under the care of a matron and other female officers.

What runs through all this is the activities of women who wanted to be involved in that ideal of service: the wish to serve, to do something for the betterment of mankind and to offer practical help in the advancement of a society on the rise, which was the case at the climax of Victoria’s reign, when the Empire was ascendant, and for generations the women of Britain had sustained the great imperial enterprise by providing sons for administration and militarism. Within this there was the quiet but insistent push towards women’s education.

Charity was more than simply an option to do something useful to others; for many women it was the best move towards a professional career. This can be seen in the life and work of Beatrice Webb, as she explains in her autobiography:

It was in the autumn of 1883 that I took the first step as an investigator.… What had been borne into me during my book studies was my utter ignorance of the urban working class, that is, four-fifths of my fellow-countrymen. During the preceding London season I had joined a Charity Organization Committee and acted as one of its visitors in the slums of London.

In one particular life we may see exactly what kind of quest and challenge this was: the woman was Emily Davies, whose portrait hangs in Girton College, Cambridge, and whose memorial reads: ‘Throughout her life a leader in the struggle for the education and enfranchisement of women. By her faith and unwearied efforts this college was founded and established.’ She was born in 1830, and lived to the grand old age of ninety-one. After early struggles to establish local examinations for women, so that they could matriculate and eventually perhaps be awarded degrees at universities, a turning point came in 1869 when the new college for women, growing from an executive committee, became closer when an experimental establishment was formed at Benslow House, Hitchin. Then, in 1873, at Michaelmas Term, Girton College was opened.

As Emily’s biographer, Daphne Bennett, wrote, what was achieved was ‘a family of women’, but much more. Gradually, the girl students were allowed to participate more in university life, rather than being part of some strange experiment; lectures in medicine were opened up to them, for instance. This meant that a mixed medical class would have to be handled by the authorities. After a very long time, higher education for women was becoming a reality. The University of London opened its doors to women in 1878; Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall started in 1879. Then, in 1882, the issue of certificates for women was allowed, certifying that they had...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Charity, Education and Good Works

- Chapter 2: The First Law Students and the Women Lawyers

- Chapter 3: From One War to Another: The Policewomen Arrive

- Chapter 4: From Women Jurors to Magistrates

- Chapter 5: Behind Prison Walls

- Chapter 6: Wartime and Post-war Policewomen

- Chapter 7: Probation Officers and Legal Executives

- Chapter 8: The ‘Lady Detectives’

- Chapter 9: Sheriffs, Lord Lieutenants and Coroners

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography and Sources

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Justice Women by Stephen Wade in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.