- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

It is not widely remembered that mines were by far the most effective weapon deployed against the British Royal Navy in WW1, costing them 5 battleships, 3 cruisers, 22 destroyers, 4 submarines and a host of other vessels. They were in the main combated by a civilian force using fishing boats and paddle steamers recruited from holiday resorts. This unlikely armada saved the day for Britain and her allies. After 1916, submarine attacks on merchant ships became an even more serious threat to Allied communications but submarines were far less damaging to British warships than mines.This book contains the following:Mines in WWIMain cause of ship losses; The Konigin Louise; Loss of Amphion; The Berlin; Loss of Audacity; Losses in the Dardanelles; The Meteor; German mines and how they worked; Minefields - British and German; Fast minelayers; Submarine minelayers.Formation of RNMRPersonnel and discipline; Sweeping technique and gear; Trawlers and drifters; Paddlers; Fleet minesweepers; Sloops.ActionsEast Coast and the Scarborough Raid; Dardanelles; Dover Straight; Mine ClearanceSome Typical IncidentsMine strikes and Mine sweeping.StatisticsMines swept; Ships lost; Minesweepers lost.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hidden Threat by Jim Crossley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Origins

The idea of blowing up an enemy ship with some kind of explosive device is as old as gunpowder itself. The first successful attempt was in 1585 by the Dutch, who succeeded in blasting some Spanish ships using ‘exploding boats’, but these weapons cannot really be classified as ‘mines’ as they lacked one essential ingredient – they did not explode under water. A mine in the proper sense of the term must be a device intended to explode under water, where it can do maximum damage to its victim and where the surrounding water pressure makes the explosion more effective than it would be on the surface. Obviously, the construction of a true mine would have to await developments in engineering and of materials that were not available until the early stages of the industrial revolution of the eighteenth century.

The deployment of an underwater weapon was first attempted during the American War of Independence. It is significant that this was a situation in which a nation with a very weak naval power (the American revolutionaries) was attacking one with a strong navy (Britain). For many years thereafter the mine was regarded as the weapon of a weak power, and this was to lead to severe problems for the British in the future. It is important to point out at this stage that what we would call ‘mines’ were in the eighteenth and nineteenth century often called ‘torpedoes’ and torpedoes were sometimes called ‘locomotive mines’. It is easier to understand accounts of warfare at that time if this is kept in mind.

The pioneer of mine warfare was an American called David Bushnell. His first attempt (September 1776) was against the British frigate Eagle, flagship of Lord Howe. He had devised a primitive submarine named the Turtle. Turtle was an egg-shaped device about six feet from top to bottom, which accommodated a single occupant, Ezra Lee, a sergeant. Lee had two screws that he turned by hand, one horizontal to give forward movement, and one vertical. There was also a rudder and a water pump to control ballast weight. Together these must have kept Lee pretty busy. A tiny conning tower projected above the water to enable Lee to see where he was. On the outside of the vessel was a magazine containing 150 lb of gunpowder. There was a screw attached to the magazine by a lanyard, and this was to be inserted into the enemy vessel, and a thirty-minute clock started; the clock would then detonate the magazine when Turtle had had a chance to get clear. Turtle was towed to a concealed point up tide of Eagle, which was lying in New York Harbour, close to Governor's Island. At first Lee was carried past Eagle by the tide, but he managed to get back to her and tried to insert the screw. It was impossible, however, to penetrate the copper sheathing around her hull. As daylight approached, the sergeant had to abandon his mission and released the magazine, which drifted away harmlessly. Lee escaped unhurt.

Bushnell made several more attempts against British shipping. One ‘magazine’ was launched against a frigate Cerberus, but it missed her and struck a small schooner close by causing several casualties. He then adopted a much more promising tactic, this time drifting kegs of explosive slung below floating buoys down towards ships lying in the Delaware River. Unfortunately for the Americans the river was starting to freeze over at the time of launching, and this had caused the British to move their ships clear of the main stream, and out of the main path of the drifting kegs. Also the ice delayed the progress of the kegs down tide so that they arrived in daylight, not in the dark as intended. In daylight it was not difficult for the British to fend off any kegs getting near their ships, but one boat's crew, attempting to capture a keg, was insufficiently careful and it blew up killing four men and wounding others. Thus Bushnell's campaign came to an end without conclusive result.

In the French revolutionary wars an American citizen, Robert Fulton, made a number of attempts to interest both the French and the British Governments in a device that he had invented, not entirely unlike Bushnell's, for getting an explosive charge tethered to the hull of an enemy ship. The vehicle for delivering the mine, named Nautilus, was a copper-sheathed iron submarine, equipped with a sail for use on the surface and a hand-driven screw for underwater propulsion. Some successful trials were conducted, but both the British and the French considered the device ‘dastardly’ and did not use it. The British did, however, attempt to use ‘explosive catamarans’ proposed by Fulton, against the French fleet off Boulogne in 1804. These were not very successful, and the whole enterprise was considered rather unsporting. No such nice moral judgements were to apply in the savage total wars of the next century.

Fulton was not finished. In 1804 he came up with new proposals, including one for a moored mine that consisted of a brass case containing 100 lb of gunpowder with a firing pin on top. This was provided with buoyancy by cork. It had one entirely novel feature, which was a system for locking the firing pin after a pre-determined period so as to render the mine harmless. Thus, it had many of the characteristics of a twentieth century sea mine. It was never used in practice. Yet another Fulton development, made during the Anglo-American war of 1812, was a submersible vessel with a turtle-shaped metal shell designed to protrude slightly above the water. This towed a number of ‘torpedoes’ as it proceeded through an enemy anchorage. The ‘torpedoes’ were released and detonated as they struck enemy ships. One of these devices was captured by the British when it went aground on Long Island in 1814 and this appears to be the only one ever used in anger. Fulton died in 1815. His career as an armaments manufacturer was not notably successful, although some of his ideas formed the basis of subsequent successful developments. Interestingly, his motive was not money or even patriotism. He genuinely believed that his devices were so awful that they would make war at sea in future inconceivable to intelligent humans. A man of many parts, he was also a notable artist and a pioneer of steam-propelled boats.

At this point it is necessary to distinguish between different types of mine that would come into use in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These can be divided into the following general categories:

Ground mines

These are mines designed to sit on the seabed, typically to protect a harbour from enemy attack. These are frequently controlled from an observation station on shore and detonated when an enemy ship is in the act of entering the harbour.

Drifting mines

These are normally allowed to drift under the influence of tides or currents, in the way that Bushnell's kegs were used in the Delaware River. Drifting mines can also be released by a fleet fleeing from a superior enemy in the hope of destroying some of his ships. As we shall see, the British became very concerned about such tactics during the First World War.

Some quite ingenious drifting mines had been designed that creep up rivers on the rising tide and stay still on the ebb.

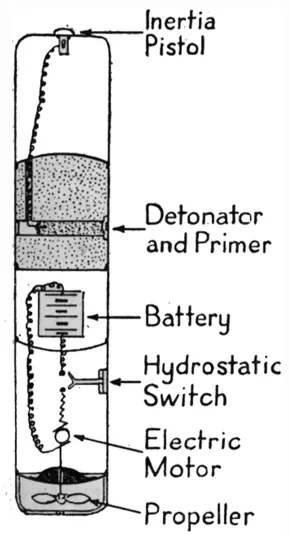

Figure 1: A Leon mine. These were designed to drift free, with depth being maintained by an electric motor and hydrostat. When the battery was exhausted, they sunk to the bottom. In practice they were not much used, although the Royal Navy did sow some in the North Sea.

Normally, drifting mines have some sort of self-destruct device so that they do not constitute a permanent hazard to shipping.

A more elaborate type of drifting mine was known as the Leon mine (see Figure 1). This was a drifting mine designed to maintain a pre-set depth under water by means of a hydrostat and a small electric motor that actuated a vertical propeller, rotating in either direction so as to drive the mine either upwards or downwards. Leon mines could be launched into a harbour or anchorage and would drift towards an attacking enemy fleet, detonating when struck by a ship. They might also be dropped by a fleeing warship so as to threaten its pursuers, or so as to drift down tide towards an enemy fleet. They had a limited life and would sink harmlessly to the bottom when the battery ran out of power.

Moored mines

These are by far the most widely used type, and are moored to the sea bed by a cable. They can be detonated in a number of ways:

• By contact using a trigger mechanism outside the mine itself.

• By ‘influence’, either magnetic or sonic.

• By means of long whiskers or antennas projecting from the mine.

• By remote control by an observer on shore.

Normally, moored mines have a deactivating device that makes them safe if the mooring line should part.

Limpet mines

These are fixed to the hull of an enemy ship by frogmen or midget submarines.

After the Anglo-American war, the next use of mines in warfare was during the Schleswig-Holstein war of 1848–51 fought between Prussia and Denmark. Denmark had by far the most powerful fleet and the Prussians feared that they would use it to force their way into Kiel harbour. They employed a system of ground mines that could be set off by means of an electrical current from on shore. This had been devised by Professor Himmel of Kiel University – an early example of a ‘boffin’ being used to gain military advantage. The system was successful in that the Danish fleet was deterred from forcing an entry.

Much more extensive use of mines was made in the Crimean War (1854–6). Russia was at war with Britain, France and Turkey, and being the weaker power at sea, was active in employing mines to protect its harbours. Two types of mine were used. Ground mines detonated by observers on shore were employed, as well as moored contact mines containing 25 lb of gunpowder, which incorporated a most ingenious fuse that was to be the forerunner of the system used for many years almost universally. A glass tube was encased in a lead ‘horn’ that would bend as soon as it was contacted by a ship, breaking the glass tube. The broken tube would release the sulphuric acid that it contained into a mixture of potassium chlorate and sugar. This caused a small explosion, which in turn detonated the gunpowder. These were sometimes known as ‘Nobel mines’, after their inventor (the father of the famous Alfred Nobel) Immanuel Noble. At least two British ships were damaged by these mines when they attempted to approach the Russian base at Kronstadt in the course of the war. At the same time the Russians employed some large ground mines with electrical detonation. These do not appear to have been fired.

The American Civil War (1861–5) saw extensive use of mines mainly by the Confederates – again the weaker naval power. Many of the mines used were simple kegs of gunpowder, often laid in pairs with a friction device like a match head to fire them when they were struck. As an alternative, some were fitted with chemical fuses similar to the Russian horns. A more elaborate type of mine, the Singer mine, consisted of a metal cone filled with gunpowder, on top of which sat a heavy metal lid secured to a length of chain. These were tethered a little below the surface of the water. When a vessel hit the mine the lid was dislodged and fell off, jerking on the chain and setting off a friction fuse. The Singer mines were remarkable in that if the lid was knocked off by accident when the mine was being laid, a safety pin prevented the fuse from being activated. Another innovative development was known as ‘The Devil Circumventor’. This was a mine designed to be laid in shallow rivers. It consisted of a case containing 100 lb of gunpowder, fitted with detonating horns. This was mounted on top of a spar, which in turn was connected to a universal joint on top of the anchor weight that held the whole device to the bottom, so that it stuck up rather like an underwater lollipop. Connected to the anchor was another mine sitting on the seabed, so that any attempt to sweep the device was sure to detonate the underwater mine. This was the first example of an anti-sweeping system. Ground mines were also employed by Confederate forces, one containing 1,000 lb of gunpowder and detonated electrically, successfully destroyed a powerful Federal gunboat.

No account of mining in the Civil War can be complete without mention of the use of towed mines or ‘spar torpedoes’. Spar torpedoes were explosive devices mounted on long spars sticking out from the side of fast-moving steam launches or stealthy semi-submersible boats. These would be manoeuvred so that the mine on the end of the spar would strike the target and explode. A further development of the same principle consisted of a launch that would tow a mine behind it on the end of a long cable. The launch would then try to cut across the bows of a moving target so that the mine struck it. These weapons were extremely risky to those who used them and were to be rendered obsolete by the introduction of quick-firing secondary armament and self-propelled torpedoes. Nevertheless, they were employed by both sides and achieved some notable successes.

In all, twenty-two ships were destroyed by mines during the Civil War, and many more severely damaged. The mine had decidedly come of age.

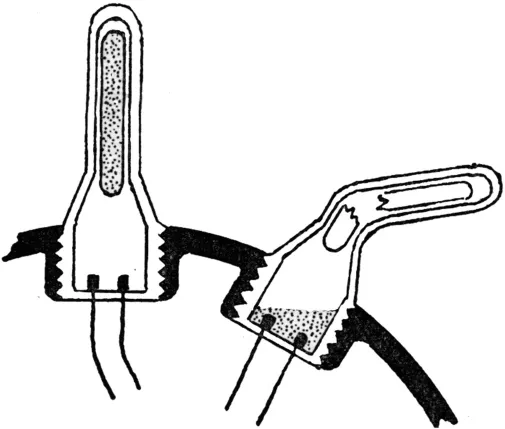

Two final nineteenth century wars saw a further significant development in mining technology. The Austro-Prussian war of 1866 saw the development of the Hertz horn, which was first incorporated in German mines during this conflict (see Figure 2). The Hertz horn was to become a feature of the vast majority of contact mines used in both world wars. It consisted of a lead horn containing a glass tube similar to the Russian mines described above, however in this case, instead of a chemical reaction, the fuse acted electrically. Breaking the glass tube released a bichromate solution onto two plates, one zinc, the other carbon. This immediately constituted a battery and generated an electrical current that passed to a platinum wire bridge embedded in fulminate of mercury; the current fused the bridge and ignited the priming composition, which in turn fired the main charge. This elegant device acted almost instantaneously and proved reliable and long lasting in service. Mines fitted with Hertz horns protected German harbours against the greatly superior French fleet in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and thereafter the German Navy paid great attention to the manufacture and deployment of moored mines.

Figure 2: The Hertz horn. A ship striking the soft lead horn bends it and breaks a glass tube inside, which allows acid to contact two electrodes, setting up a battery that immediately generates a current detonating the mine. By far the most satisfactory system for detonating contact mines.

In the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–1905, mines were to prove a decisive weapon. The Russian Pacific Fleet was bottled up in Port Arthur. Russia was at the time probably the world leader in mine design and manufacture, having successfully used them in the Crimean war and in the subsequent Russo Turkish war. By 1904, Russian mines used either the Nobel or the Hertz firing systems and were filled with guncotton instead of gunpowder. They were mostly conical in structure with a single horn projecting out of a domed top.

Japanese mines drew the first blood, however. At first, the Japanese had failed to obtain decisive results by attacking the Russian fleet in harbour using torpedo boats. These did no great damage but seem to have demoralized the Russian Navy so that it did not interfere with Japanese troop landings behind the town. The supine performance of the Russian Navy prompted the selection of a more aggressive commander. Vice Admiral Stepan Makaroff was dispat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- ‘The Minesweepers’ by Rudyard Kipling

- Introduction

- 1 Origins

- 2 Mines and the Royal Navy

- 3 German Minelaying and the British Response

- 4 The Gallipoli Campaign

- 5 The British Mine-laying Offensive

- 6 Clearing Up

- 7 Conclusion

- Index