eBook - ePub

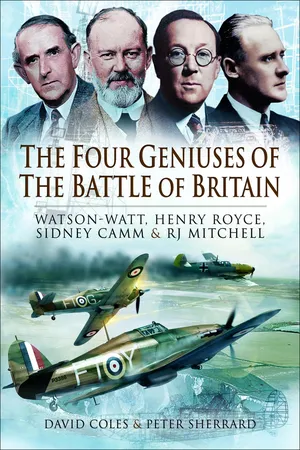

The Four Geniuses of the Battle of Britain

Watson-Watt, Henry Royce, Sydney Camm & RJ Mitchell

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Four Geniuses of the Battle of Britain

Watson-Watt, Henry Royce, Sydney Camm & RJ Mitchell

About this book

"Had it not been for the vital contributions of the four men and their inventions described in this book the Battle of Britain could not have been won by the Royal Air Force. Each of these brilliant men contributed enormously to the aircraft and equipment upon which the gallant RAF fighter pilots depended to take on and defeat the hitherto overpowering Luftwaffe during Hitlers European onslaught. Watson Watt was the moving force behind Britains vital early warning radar network that allowed Allied fighter aircraft to intercept the incoming German bomber raids. Henry Royce was the driving force throughout the development of the Merlin engine that powered both the Hurricane and Spitfire.Sydney Camm persevered with the design of the Hawker Hurricane which was to destroy more Luftwaffe bombers in the Battle than any other type. It was amazingly resilient and provided an extremely stable gun platform. Never living long enough to see the success of his beautiful Spitfire, RJ Mitchell was the designer of the only British aircraft that could outperform the Nazi Bf 109s fighters and which allowed the attacking Hurricanes a little more safety while doing their job below. This is the story of those men behind the scene of the greatest air battle in history. "

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Four Geniuses of the Battle of Britain by David Coles,Peter Sherrard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Robert Watson-Watt – Radar’s Inventor

‘A man’s a man for a’ that.’ Burn’s poem well describes Robert Watson-Watt, the major inventor of radar. He was born at 5 Union Street in Brechin on 13 April 1892, one of three sons of a carpenter. He did not start out as a member of the upper crust; but from his early days he reached out for all he was given, to impart his knowledge to others in turn. His father may have expected that Robert would follow in his footsteps and work in the family business, as many other Scots have done. But Robert showed a great interest in science and looked more likely to follow in the footsteps of his famous far distant ancestor, James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine.

As a child he loved and respected his family, gaining their regard as he went to a fine school, Brechin High. He later remembered his teacher Bessie Mitchell as one ‘who did more than any other teacher to make me whatever I am’. He did well there and won a scholarship to University College, Dundee, to study engineering. He graduated with a BSc (Eng.) and was offered a position with Professor William Peddie, who introduced Robert to the seemingly never-ending possibilities of radio waves. While at Dundee, Robert met a Perth girl, Margaret Robertson, who was studying art at Dundee Technical College. They married in 1916 and Margaret became an important part of Robert’s radio wave experiments, when he used her skills as a jewellery maker to repair his wireless apparatus. She was a responsible, well educated lady, who transcribed the Morse-coded messages from Paris to the Aldershot command, passing on the radio transmissions that finally played such a part in that greatly desired Armistice Day, 11 November 1918.

Robert was fortunate having excellent mentors and he could take up one skill from another, from craft and classics to science. He was much more than that. Later he understood that Nazi Realpolitik focussed on unbridled power. Its unprincipled immorality and power-lust worried him so much that he later speeded up his radar program. A lesser man would have said, ‘So what?’

He had a great ability to inspire a fine team of engineers and craftsmen, and he must have known the great thrill of invention, as he moved from tracking lightning to radar. His major change in direction occurred when in January 1935 H.E. Wimperis, Director of Scientific Research at the Air Ministry, questioned him on German death ray work, and Watson-Watt quickly returned a calculation from his assistant, Arnold Wilkins, showing that it was impractical. But he also mentioned in the same report that attention was being turned to the difficult, but more promising, problem of radio detection of aircraft. He submitted numerical considerations for this detection by reflected radio waves, and this ultimately led to radar, grounded in complex physics.

The concept of radar could even have been sown earlier when he found that aircraft disturbed lightning tracking. You can imagine the younger Watson-Watt saying with great heat and frustration, ‘You never can track anything at 10.30 when that mail plane goes over!’ Then one day he is inspired, ‘Now that is a brilliant way to track aircraft! I’ll put it in the logbook, in RED.’ Maybe that is how Watson-Watt started to lay the practical and theoretical groundwork for radar during investigations into atmospheric disturbances. He said later ‘Give them the third best to go on with; the second best comes too late; the first never comes.’ That’s true, and in no way nonsense. Advanced gear such as the klystron (a single resonant cavity device) came later but developers had to do the best with what they had then. By the time better ideas had arrived with their improved gear, the Germans would have overrun us. The cathode ray tube, the primitive predecessor of the TV tube, was invented during the 1920s and 1930s. Watson-Watt was also central to the development of other useful hardware such as the goniometer. Such work has its lows and highs, its frustration and blinding enlightenment, and he wasn’t a stranger to these either.

What was the option if radar had never been invented? The large fixed acoustic detector was installed at Denge near Romney in Kent and, pointed at Amiens, but its range was only guaranteed for eight miles, twenty-four at best. As it was fixed, after reconnaissance the enemy could have easily by-passed it by making flank attacks up the Thames on London. We set up smaller steerable detectors, as well as mobile army units with range less than the larger fixed unit and its optimized design, but what a hope! Our aircraft would have barely left the ground before the Germans were upon them. It must be remembered that war is not a sport!

Then there were the death ray and ignition killer concepts. The cover of a novel from the 1930s showed a flight of enemy aircraft falling over the edge of an invisible cliff of air. In reality you needed to reach the power and frequency of radio waves required to do one or the other. Death ray equipment would kill its operators if any power leakage occurred, and it was virtually impractical before any suitable hardware evolved. A death ray at a level then attainable would have barely given an enemy pilot a headache, but it might have warmed him up. Lasers weren’t invented, so there were no practical means of stopping enemy aircraft, other than shooting them down. You have to find them to do that. This then would require us to deploy standing patrols with their high pilot and aircraft wastage, and need for massive fuel stocks. The Germans then held all the initiatives to mount an airborne offensive from any point of their choosing. At the same time their submarines would be able to sink the tankers bringing in our oil supplies. Standing patrols would overload our resources in the most even-handed battle. We could reach no better than stalemate then, unable to continue and conclude the future war.

So we had to wipe the slate clean and start again. If we hadn’t got an answer ready, then we couldn’t possibly respond in an emergency.

In 1932 our Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin said, ‘The bomber will always get through.’ But not all the British Air Ministry felt that was inevitable. In June 1934, an Air Ministry official, A.P. Rowe, went through the plans for British air defence, and was horrified to learn that our aircraft were being improved, but little was done to come up with a broad defensive strategy. Rowe wrote to his boss, Henry Wimperis, telling him that inadequate planning was likely to prove catastrophic. Wimperis took the memo very seriously and went on to propose that the Air Ministry must look into new technology for defence against air attacks. He suggested that a committee should be led by Sir Henry Tizard, a prestigious Oxford-trained chemist, the rector of Imperial College of Science and Technology. So a new ‘Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence’ (CSSAD) was directed by Tizard, with Wimperis as a member and Rowe as secretary. Wimperis also independently investigated other possible new military technologies.

The Air Ministry had a standing prize of £1,000 to be awarded to anyone building a death ray that could kill a sheep at 200 yards. Hindsight makes the idea seem silly, but some British officials were worried that the Germans were working on such weapons, and Britain couldn’t afford to be left behind. Some studies were conducted on intense radio and microwave beams, on the lines of modern ‘electromagnetic pulse’ weapons. Wimperis contacted Robert Watson-Watt, then head of the National Radio Research Laboratory, regarding death rays. A cheery, tubby man, Watson-Watt was highly intelligent and full of drive, but with a tendency to talk at length in a one-sided fashion. His most important ability was that he had developed a radio and triangulation system to locate thunderstorms, a most useful transferable skill.

After some informal studies and consultations with members of his lab, Watson-Watt told Wimperis that he thought death rays were impractical. However, he added that he could detect enemy aircraft by bouncing radio beams off them. Wimperis realized that such a concept worked well within the CSSAD’s mandate, and put the idea to the committee members. They were interested, and in response Watson-Watt fleshed out his ideas in a memo dated 12 February 1935. He invented radar, faced with the problem of enemy aircraft detection. Only four years later his system tracked the incoming Luftwaffe far out to sea. Watson-Watt and Arnold Wilkins brilliantly drew up the radar document; ‘brainstorming’ at its best, well before the word existed.

Detection of the enemy is essential to his destruction. This starts with irradiating an aircraft with a radio beam, which makes it act like a ‘half-wave’ element. A voltage then develops along the largest part of the aircraft and induces a current in it, which generates a return signal. But your detector receiving the echo has to be tuned softly or you may detect a bomber but not a fighter. There are other problems if you persist in sharp tuning. If the aircraft turns then it appears to shorten and may vanish altogether, as the demodulated return signal then decreases sharply. But soften the tuning with a shunt resistor and there you are, as I remember proving for myself at RAF Locking.

The document considered so many things essential to a practical radar system, such as the measurement of the range of the target aircraft and its presentation. The first element is a transmitter feeding an aerial sending out pulses like a floodlight; it also triggers receiver circuitry. Watson-Watt used the cathode ray tube he had for ten years, showing the target as a vertical pulse shifting from its X-axis line at a distance along its face shown by range markers. The distance to the target is proportional to the return time of the transmitted beam (10.74 micro-seconds per statute mile). Right from the start he set 190 miles as a useful range for his system. Range is essential, but where is the target? So he had to find the target’s bearing and height to define its position in 3-D. Bearing can be aligned to the receiver aerial system by a goniometer adjusted for its accurate return of direction. An easy way to find the target height is to get the target’s elevation above horizontal, and apply maths to the range. Correct this for the earth’s curvature and there you are! He considered every way to get answers to the problems presented to him, such as continuous wave and frequency change techniques.

Next he proposed IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) to discriminate between RAF and Luftwaffe aircraft. IFF seems a luxury, but it was really essential. Our fighters may have been alerted to shoot down an unidentified aircraft in our skies, putting a lone RAF pilot in jeopardy. Conversely, a German pilot may have roamed around British skies at will. Our radar triggered the IFF secondary pulse transponder in a British aircraft, which showed that by its modified radar plot that it was friendly. Finally, Watson-Watt appreciated the need for RAF Ground Control, as that followed radar naturally in the development of an operationally simple system. The assembled plots on a large map allowed ground controllers to discriminate easily between German and RAF flights using our later VHF radio link. Working in parallel with IFF, Ground Control could then call up a patrol to deal with a German attack shown on the map, in ideal conditions anywhere in Southern Britain. So standing patrols ceased to be needed, and that solved a frightening problem. The Observer Corps used high grade binoculars to identify enemy aircraft numbers and types, to complete the picture. With modern day technology you could do that with radar as well, but in those days the Observer Corps gave us the immediate, low-tech answer and final piece in the jigsaw!

In all these advances, Watson-Watt was ably helped both by his superiors, among them Tizard and Lord Swinton, and his own team including Rowe and Wilkins. But without his leadership and drive, little of this could have happened. His team was so small that it was overloaded in dealing with all the ideas it conceived.

With this foresight, Watson-Watt was brilliant in his anticipation of what was needed. Later he analysed his dependence on his radio predecessors, Henry Jackson in Britain, Heinrich Hertz and Christian Hulsmeyer in Germany, and Guglielmo Marconi in Italy. These were the ‘Prior Artists’, but Watson-Watt took the critical onward steps from their basic ideas. From his experience he knew that the electromagnetic spectrum properties were not cohesively unified. Typically, radio waves cease to be reflected between the earth and the ionosphere at higher radio frequencies, when they disappear into space. To reach a new realm of thought and come up with a new patent, there must be a need for new techniques and hardware, at that point to stop a coming German invasion. The hardware was there or nearly so, and he used it to implement many new techniques to bring radar to fruition.

The CSSAD was enthusiastic about radar, but had to move from paper ideas to demonstrate the concept before the Air Ministry granted development cash. So the starting point in British radar history was the demonstration held in Daventry prepared by Watson-Watt and his team before dawn on 26 February 1935, successfully proving that radar could detect aircraft, to the satisfaction of all the civil servants and RAF officers involved, Dowding in particular. So now radio waves would spot planes!

The demonstration used the 10kW Daventry short wave transmitter, operating not in pulse mode but in continuous wave mode at 6MHz (50 metres). At the aerial site in a field south of Weedon, seven miles from the transmitter, the amplified outputs of two horizontally polarized receiving aerials, pointing towards it, were first adjusted on a CRT (cathode ray tube) to give a null signal when no aircraft were present. These aerials were fixed to two 15 feet high posts, 50 feet apart, set on a straight line joining the transmitter, aerial 1 and aerial 2. The CRT gave a well defined signal when Squadron Leader R.S. Blucke flew the Heyford bomber shown, over the line extending between the transmitter and receivers to 20 miles out from the transmitter, at a height of 6,000 feet. So detection using radio waves worked and radar was viable, at that time not using the pulse techniques much loved by the author, but this was a real start and no mistake! It was brilliantly done using existing gear such as the Daventry transmitter. Even the receivers were simply modified existing equipment – it must have taken only a day to modify one of them for the test. This was done frugally; the most expensive part of the demonstration would have been the Heyford flight! Watson-Watt was so heavily involved in discussion after the demonstration he completely forgot to pick up his twenty-three-year-old nephew at the finish! He was so impressed that he said, ‘Britain has become an island again!’

Dowding now made radar ‘MOST SECRET’, and backed the project to the tune of £12,300, then a massive sum, for development of the new radio echo detection system.

At the Daventry demonstration an Air Ministry man observed, ‘It was demonstrated beyond doubt that electro-magnetic energy is reflected from the metal components of an aircraft’s structure and that it can be detected.’ Later the Scientific Survey of Air Defence group stated, ‘The result was much beyond expectation.’ The RAF officers there could have sat on their hands and said, ‘What a scheme! It’s a pity we can’t afford it!’ Instead they spent millions of pounds and saved their country from a bitter defeat at the hands of the Germans. But in the words of Wellington at Waterloo, our future victory in the air was ‘a damned close run thing!’

Another facet in Watson-Watt’s character appeared from this time onwards, the ability to keep his mouth shut. This was hard for a man more used to broadcasting success. His awareness of the degeneration of the German psyche, from the start of the Nazi regime, made him accelerate the progress of radar development. He completely understood what was needed of a radar system – detection, ranging, direction-finding, height-finding and, finally, reporting. The importance of reporting was later shown by its horrific failure at Pearl Harbor in 1941, when a junior radar operator saw that a large force was approaching without notification, but somehow his warning of the Japanese raid did not reach his senior officers. So, if reporting failed, then its failure made the whole system useless. After that, you can’t blame Watson-Watt’s recognition of his own self-worth; or as the Scots would put it, he had ‘a Guid Conceit o’ Himsel’.

Early radar – Chain Home (CH)

Radar was well on its way. After intense brainstorming, late night sessions, and hard work, Watson-Watt’s team, notably including Arnold Wilkins and Edward Bowen, developed a working pulsed radar system in June 1935. The transmitter array consisted of two tall towers with antenna wires strung between them, while the receiver array consisted of two similar arrays arranged in parallel. The number of arrays was increased later, but now an exercise at Bawdsey gave nine reports per hour on 18 September 1936, improving to 124 in 115 minutes, six days later. The first five bi-static Chain Home (CH) radar stations at Bawdsey, Canewdon, Dover, Dunkirk, and Great Bromley were completed by July 1938, ready for the August 1938 exercise. Their transmitters and receivers were separated by about 300 yards at bi-static stations.

Range

The CH system schematic diagram on the next page shows the RAF radar system driving the Synchronizing Pulse Generator (Sync. Pulse Gen.). If the RAF system was damaged, the Sync. Pulse Gen., the radar station master circuit, oscillated in a free running mode. Ideally, interference between our radar stations could be minimized by using mains synchronization or a national 400Hz source via land lines. Each radar station realistically needs its own back-up power and synchronization in readiness for battle conditions. In either case its 400Hz p.r.f. (pulse repetition frequency) pulse output triggered the Transmitter Power Driving Circuit and Array to send the radar pulse. It also started the time-base and range marker generators. The target aircraft reflected the radar pulse back to the receiver array and receiver circuit, whose output was fed to the CRT ‘Y’ plates as a negative pulse. The range markers were fed to the ‘Y’ plates as a series of positive pulses. The time base generator applied a linearly increasing voltage to the CRT ‘X’ plates giving the return time. This all showed the range of the target aircraft in a manner fast understood by the operator.

The system range depends on its p.r.f. and other factors, as shown in the diagram.

Bearing

The next data required from the system was the target bearing. CH transmission had a direction with the most pulse energy, the Line of Shoot. Aligned to the ‘shoot’, the aerial on the receiver tower comprised two pairs of horizontally aligned crossed dipoles. Each pair was fitted at a mean height of 215 feet, 5 feet either side of the centreline, set mutually at right angle...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1 - Robert Watson-Watt – Radar’s Inventor

- Chapter 2 - Frederick Henry Royce and the Merlin

- Chapter 3 - Sydney Camm – The Designer of the Hurricane

- Chapter 4 - Reginald Joseph Mitchell and the Spitfire

- Chapter 5 - The German Terror Weapons

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index