- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author of

Guarding Hitler delivers "a study revealing the Japanese use of Allied POWs in medical experiments during WWII."—The Guardian

The brutal Japanese treatment of Allied POWs in WW2 has been well documented. The experiences of British, Australian and American POWs on the Burma Railway, in the mines of Formosa and in camps across the Far East, were bad enough. But the mistreatment of those used as guinea pigs in medical experiments was in a different league. The author reveals distressing evidence of Unit 731 experiments involving US prisoners and the use of British as control groups in Northern China, Hainau Island, New Guinea and in Japan. These resulted in loss of life and extreme suffering.

Perhaps equally shocking is the documentary evidence of British Government use of the results of these experiments at Porton Down in the Cold War era in concert with the US who had captured Unit 731 scientists and protected them from war crime prosecution in return for their cooperation. The author's in-depth research reveals that, not surprisingly, archives have been combed of much incriminating material but enough remains to paint a thoroughly disturbing story.

"The narrative does not seek sensation or attempt to draw irrefutable conclusions where it is clearly impossible to do so, instead it simply provides a balanced assessment of what is known and what seems probable."—Pegasus Archive

The brutal Japanese treatment of Allied POWs in WW2 has been well documented. The experiences of British, Australian and American POWs on the Burma Railway, in the mines of Formosa and in camps across the Far East, were bad enough. But the mistreatment of those used as guinea pigs in medical experiments was in a different league. The author reveals distressing evidence of Unit 731 experiments involving US prisoners and the use of British as control groups in Northern China, Hainau Island, New Guinea and in Japan. These resulted in loss of life and extreme suffering.

Perhaps equally shocking is the documentary evidence of British Government use of the results of these experiments at Porton Down in the Cold War era in concert with the US who had captured Unit 731 scientists and protected them from war crime prosecution in return for their cooperation. The author's in-depth research reveals that, not surprisingly, archives have been combed of much incriminating material but enough remains to paint a thoroughly disturbing story.

"The narrative does not seek sensation or attempt to draw irrefutable conclusions where it is clearly impossible to do so, instead it simply provides a balanced assessment of what is known and what seems probable."—Pegasus Archive

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

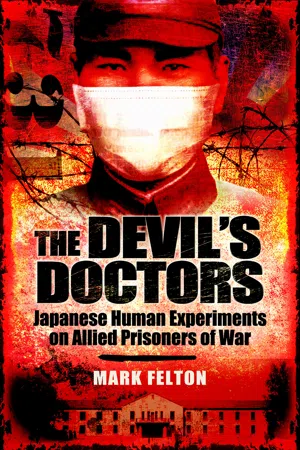

Yes, you can access The Devil's Doctors by Mark Felton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Japanese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Seeds of Death

Biological warfare must possess distinct possibilities otherwise it would not have been outlawed by the League of Nations.

Captain Shiro Ishii, 1931

The big transport ship lurched through the heavy waves, its engines noisily turning the screws that churned the water at the stern into angry white foam. The ship was filthy and dilapidated, its sides streaked with rust, and its superstructure grimy and encrusted with salt spray. Above the superstructure a single smokestack coughed thick, black smoke into the sky as the ship pounded relentlessly north. Down in the ship’s holds was a scene reminiscent of the Middle Passage – hundreds upon hundreds of white men crammed so tightly into the filthy and dark holds that they could barely find space to lie down on the hard metal deck plates. Accompanying the vision of overcrowding was a riotous cacophony of noises – moaning, coughing, shouting, murmuring and sometimes retching. The smell was rank, an accumulation of unwashed bodies, human excrement and vomit.

Peering down from the open hatches above were the laughing faces of Japanese soldiers, who smoked and chatted high above their prisoners. The ‘slaves’ whose grimy, white faces occasionally stared up at the guards with undisguised fear and loathing, were American soldiers, captured at the conclusion of the fight for the Philippines; the ragged survivors of an army that had been humbled in battle against a foe most had hitherto thought its inferior in every way, and then brutalized in captivity by an enemy many now thought beyond the pale of humanity. These prisoners were destined for a new camp and a new purpose in the Japanese war plan. For many of them, this journey to the north was to be their last. It was a one-way ticket to hell.

As with many things in early twentieth-century Japan, an interest in chemical and biological warfare came about through fear. The fear was that the Western Powers, particularly Britain and the United States – who dominated Asia at the time and who had developed these fearsome weapons first and also used them effectively during the First World War – would advance far ahead of the Japanese in this technology. The Japanese chemical and biological warfare programme was the brainchild of one rather eccentric doctor who made it his life’s work to create weapons of such destructive capacity that his name and the institution that he founded would live on in infamy. His name was Dr. Shiro Ishii, and the organisation he created would come to be known to the world as Unit 731.

When Japanese diplomats had signed the Geneva Convention in 1925, they had signed away their legal right to develop or deploy chemical and biological weapons, along with all of the other countries that had put ink to paper. Thirty-five-year-old microbiologist Ishii, who had just graduated from the prestigious Kyushu Imperial University and joined the army as a medical officer, had what can only be described as a kind of ‘eureka’ moment when he read a report about the Convention and the weapons that it prohibited, penned by a young Japanese army officer named Lieutenant Harada, who had accompanied the diplomats as an attacheé to Switzerland in 1925. The brilliant, though highly unorthodox, Ishii, who wore round wire-framed glasses and had thick, black hair, could see that chemical, and especially biological warfare (BW), weapons were immensely powerful tools of war. The framers of the Geneva Convention were influenced in their decision to ban such weapons, and research into them, by the experiences of the First World War when Mustard Gas had been widely used. They also feared a return of the Black Death, as nations with BW weapons had the potential to kill millions with the bubonic plague and other hideous forms of weaponized bacilli. The fear was similar to that expressed over the supposed ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’ that led to war in Iraq in 2003 when the United States and Britain became convinced that Saddam Hussein possessed a formidable arsenal of these Domesday weapons. The nations of the world in 1925 considered such weapons to be immoral and unnecessary. The fact that they had been specifically banned spoke directly to Ishii’s perverted thought process. They had been outlawed specifically because they were so powerful – and logically it made perfect sense that Japan should have them.

Ishii, a fervent nationalist who believed that Japan had the right to build an empire in Asia, led a one-man crusade for several years, badgering and pestering generals and colonels for interviews where he quickly and eloquently laid out his ideas for developing BW weapons in secret. It would give Japan the military edge over its likely future enemies, not least among them the Western Powers and the dreaded Soviet Union. And Ishii argued vehemently that Japan was well within her rights to develop BW weapons because the Western Powers were basically operating a hypocritical policy. He could point to the true fact that countries like Britain and Germany had signed the 1899 Hague Convention that had specifically banned chemical weapons research, but then deployed such weapons on the Western Front during the Great War. Who was to say whether these nations, and others, were not already secretly doing the same again following the Geneva Convention? High-blown diplomatic rhetoric could have masked more sinister programmes by Japan’s competitors. Ishii had a point; for although BW research was expressly forbidden, the British certainly maintained a skeleton programme at their main research facility at Porton Down in Wiltshire between the wars, allowing for its full reactivation as soon as Germany invaded Poland in 1939. The Americans, too, were as equally covert with their programmes.

Unfortunately for Shiro Ishii, the timing of his presentations and arguments to the Japanese high command was not quite right. The military had yet to move to the absolute centre of Japanese politics where it could dictate the nation’s destiny, and the democratically elected government was relatively peaceful and law-abiding on the international stage, apart from some occasional nationalistic forays into Korea and Manchuria during the 1920s.

One definite advantage Ishii identified was that Japan in the 1920s was one of the world’s leaders in medical and drug technologies, providing plenty of potential researchers and research centres should his plans have come to fruition. The Japanese were also especially proud of their humane treatment of German and Austro-Hungarian POWs that had been captured in China during the Great War. The behaviour of the Japanese had been beyond reproach, and a very far cry from how the nation would treat its captured enemies over the coming two decades. Among the international community of nations, Japan stood high both morally and scientifically. This would change quite dramatically over the coming ten years.

Was Shiro Ishii’s plan to develop chemical and BW weapons completely reprehensible, and was he ‘evil’ in the classic sense of the word? What happened later at Unit 731 and at other attached units across Asia certainly suggests that Ishii and his comrades cared little about the individual lives of those they experimented on. But some of Ishii’s psychology can be explained. Born into a noble samurai family just outside of Tokyo in 1892, Ishii hailed from the warrior class which had ruled Japan for centuries with the total obedience of the Japanese people. The Meiji Restoration in 1868 that had ushered in a newly-industrialized and progressively more democratic Japan, replaced a hereditary military dictator called the Shogun with a revitalized constitutional monarchy in the form of a compliant Emperor. But the Meiji Restoration had actually changed very little in the way of attitudes, and instead, created a new powerful elite that ran the government and the economy. It was progressive anti-Shogun samurai families who had benefitted from the opening up of Japan to Western ideas and technology, and it was these progressives who had formed the first governments, and the first major companies – a very good example being Mitsubishi, the company that was later accused of having exploited American, British and Australian prisoners-of-war as forced labourers at Mukden. The samurai formed the officer corps of the army and the navy, and they still enjoyed a pre-eminent status, just as the sons of aristocrats and the landed gentry continued to dominate the top universities, the officer corps and the government of Great Britain, the world’s foremost industrialized nation at the time. Ishii had been raised with servants looking after his daily needs, and he had been educated to be aware and proud of his social position. ‘Such rules against fraternizing with the so-called lower classes ... must have made a deep impression on Ishii,’ writes Daniel Barenblatt in his seminal book A Plague upon Humanity. ‘It made it all the easier for him and the other Japanese perpetrators of lethal human experimentation to descend into a callous disregard for human life.’1 Of course, merely being born into a gentrified family does not mean that one inherits a psychopathic or sociopathic mentality. Ishii was heavily influenced by his own personal ambitions and ultranationalism, and by the fact that later in his career, superior officers encouraging his experiments in order that Japan would win the war, surrounded him. Certainly, although he was extremely intelligent, Shiro Ishii seems to have lacked empathy towards his fellow human beings. ‘As a student, Ishii seemed to have had personality problems: more succinctly, he created problems for others. He was pushy, inconsiderate, and selfish.’2 He was also callous, and he was driven, which made for an interestingly lethal combination when such a man was placed within the Imperial Japanese Army, one of history’s most brutal fighting machines. ‘Ishii was a mass of paradoxes; loud and rude, yet also a skilled social and career climber; an ardent nationalist and a devoted scientist, but a wild partygoer too.’3 It was unusual to find such an overt social climber in Japanese society. ‘In a society where Confucian-rooted respect for superiors and a strong consciousness of hierarchy dictates boundaries of behavior, Ishii’s forward drive ran roughshod over protocol.’4 One of his ‘debased proclivities’ was sleeping with prostitutes who were under sixteen-years-old. Author Daniel Barenblatt has labelled Ishii a ‘highly functioning sociopath’, and this seems to be a fair assessment of the man in light of his later notorious activities.

One of Ishii’s first breakthroughs with the army was his invention of a portable water-filtration device that could be used by troops in the field. It would enable Japanese soldiers to take water from previously dangerous places like rivers, ponds and even puddles. Any war in Asia posed the very serious threat of tropical diseases upon the armies of both sides, and Ishii recognised that it was extremely important to use science to improve the health of Japan’s soldiers. So confident was Ishii in his device, that in one notorious incident he urinated into the filter during a demonstration for Emperor Hirohito and then offered the resulting clean water to him to drink. The Emperor understandably declined, but Ishii was noticed in a very positive way. In another stunt later in his career in 1937, Ishii went to the home of Finance Minister Korekiyo Takahashi. On gaining admittance to the house, Ishii went straight into the kitchen carrying a flask of cultured cholera bacteria. Unless Takahashi immediately granted him a large appropriation to secretly fund BW research, Ishii threatened to pour the contents of the flask all over the kitchen. Takahashi called Ishii’s bluff and refused, but swiftly changing tack, the crazed scientist staged a twenty-four hour sit-in, driving the Minister to distraction with his constant badgering until the old man relented and granted Ishii 100 million yen in secret funding. From this grant came the financial support that eventually led to the creation of Unit 731.

Ishii did do some good things before the moral vacuum of Unit 731. Apart from the water-filtration device, in 1924 he was part of a groundbreaking research team who managed to identify a deadly disease subsequently known to science as Japanese B Encephalitis that killed 3,500 people on the island of Shikoku. In a completely different area, Ishii had first demonstrated an interest in using humans as test subjects. As a young army captain in 1927, shortly before his conversion to BW weapons research, Ishii and a colleague had written a very well-received academic article on their research into treating gonorrhea patients. However, the research methodology may have been the catalyst that led Ishii into the field of human experimentation, for the two doctors actually deliberately caused fever in patients through transplanted cells in order to treat the gonorrhea and ultimately to heal the patients. Between 1928 and 1930 Ishii conducted a self-financed world tour, interviewing all of the leading scientists who knew anything about BW research around the globe. His arrival back in Japan was fortuitous, for the political climate had shifted towards the military, and for an ambitious army doctor like Ishii, the rapid advancement of his career became a definite possibility.

In 1928 Japanese agents had attempted to destabilise the northern Chinese province of Manchuria by assassinating the ruling warlord. It was, as with so many ‘regime changes’ in our own lifetimes, primarily about resources and money. China at this time had no really effective central government. A group of competing warlords, mostly former generals, had controlled the country since the breakdown of the first republic created by Dr. Sun Yat-sen after the last imperial dynasty, the Manchu or Qing, had been overthrown in 1912. A former Imperial general named Yuan Shi-kai had declared himself emperor, but although his reign was measured only in days, the resulting political instability had led to the central government’s collapse and the rise of warlordism in the provinces. This meant that China was to all intents and purposes one great big financial opportunity. The British had controlled Hong Kong since the victorious conclusion of the First Opium War in 1842 and they dominated China’s most important commercial city, Shanghai, ruling it behind a consortium of business and municipal entities alongside the United States and France. The entire east coast of China was dotted with foreign concessions inside the port cities, meaning that most of the nation’s trade was in the hands of foreign business concerns. China was independent in name only. Japan already controlled Manchuria’s Liaodong Peninsula (known as the ‘Kwantung Leased Territory’), which had been ceded to them by the defeated Russians in 1905 at the conclusion of a short war between the two nations, and Japan also controlled all of the Korean peninsula and the island of Formosa (now Taiwan) off China’s coast. Other Japanese territories were the Marshall, Caroline, Marianas and Pescadores Islands in the Pacific, and the port city of Tsingtao (now Qingdao) in China which they had been awarded from a defeated Germany in 1918. It appeared to many of Japan’s military leaders that the time had come to take over the rest of Manchuria, a region that is extremely rich in fossil fuels and minerals and packed, then as now, with cheap labour.

The 1928 assassination of the Manchurian warlord brought down the Japanese prime minister’s government when it was revealed by the press, and in its place, a more right wing and militarist cabinet met. The Imperial Army saw the Soviet Union as Japan’s greatest enemy, and by seizing Manchuria, the Japanese could push their borders north into Mongolia and Siberia, with the eventual aim of conquering the Soviet Far East. They had not reckoned on a determined Red Army and a brilliant Soviet general named Georgy Zhukov who stopped their invasion attempt in its tracks ten years later.

By the mid-1930s, Japan was in the throes of an ultra-nationalist revolution with democracy slowly being pushed out of mainstream politics as reactionary elements in the military and philosophical circles loudly pointed out the inequalities of British and American ‘imperialistic’ attitudes towards Japan. The Imperial Army followed an ultra-nationalist, quasi-fascist political doctrine known as Kodaha (Imperial Way Faction), that had its genesis in the 1920s as a disparate alliance of nationalist groups formed among army officers and had eventually, by the early 1930s, coalesced into one group. Shiro Ishii and his proteégeés were all adherents, not to mention his many powerful patrons.

Imperial Way was dedicated to establishing the army as the real political power in Japan, either by winning democratic elections, or by more direct methods. Either way, the aim was the establishment of nothing less than a military dictatorship and the expansion of the burgeoning Japanese empire. The Imperial Japanese Navy, though equally nationalistic, followed a different course and made emperor worship its creed. There was considerable tension and distrust between the army and the navy in the follow up to the Second World War and throughout the conflict. The plotters suffered setbacks as well as some stunning victories.

The Great Depression, coupled with early confrontations in China, stirred the ultra-nationalists to take the lead in Japanese foreign policy. Those who stood in the way of the ultra-nationalists’ goals often paid a high price. In 1930 Prime Minister Osachi Hamaguchi successfully challenged the military radicals in the army and navy and managed to get the London Naval Conference treaty ratified by the Japanese parliament. The treaty limited the size of Japan’s rapidly expanding fleet and maintained the power balance in the Far East with the Royal Navy and United States Navy remaining bigger than the IJN, but in parity with each other.5 Many ultra-nationalists saw the treaty as an insult to Japan and a reflection of the prevalent racist attitudes of Westerners towards the Japanese people. In November 1930 a would-be assassin wounded Hamaguchi. In 1931 a military coup was planned in Tokyo but it was abandoned at the last minute. The following year naval officers actually assassinated new Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai in the hope of forcing the government to declare martial law, a move that would have placed the military in effective control of the nation. But their plot also failed.

In order for Shiro Ishii’s scientific ideas to become reality he needed powerful patrons, and these he began to collect in the new militarist environment in Japan. Ishii first convinced the new Defence Minister, General Sadao Araki, of the necessity of BW research, claiming that his world tour had shown him that many other nations were doing the same thing – and illegally. Major General Tetsuru Nagata was another early patron. He was an army commander in Manchuria. The Japanese had stationed small numbers of troops in the province for a decade, protecting the main Japanese economic asset in the region – the Russian-built South Manchurian Railway – from bandit attacks in an unstable China. Two of Nagata’s subordinates, Colonel Seishiro Itagaki and Lieutenant-Colonel Kenji Ishiwara, hatched a plan to bring about full Japanese control in Manchuria in 1931. They favoured invading and occupying Manchuria and replacing the government with either a Japanese colonial administration or a local puppet regime. They decided to act by sabotaging a section of the South Manchurian Railway near Liutiao Lake and then blaming local Chinese troops. This would give the Japanese Kwantung Army the pretext it needed to occupy the rest of the province, claiming to the rest of the world that they were simply protecting Japanese economic interests in the region. Itagaki, who was Chief of the Kempeitai Intelligence Section of the Kwantung Army, led the operation. The Kempeitai was Japan’s military police, a powerful and feared organisation with some parallels with the German Gestapo and SS Security Police, and the Soviet NKVD – though with a much broader remit.

The Manchurian adventure was a classic ‘false flag’ intelligence operation of the sort the Kempeitai was well-trained to conduct, and it worked perfectly. On 18 September 1931, a small bomb exploded beside the railway track, causing only superficial damage. The next morning Japanese troops attacked the local Chinese garrison which was under strict orders not to resist, and put it to flight. The Chinese did not fight back, believing that this would have led to all-out war and an even bigger disaster for their country. By that evening, Japanese troops had captured the most important city in the region, Mukden (now called Shenyang), for the cost of only two Japanese soldiers killed. Five hundred Chinese troops had been slaughtered during the assault. In spite of the high casualties, Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek continued to order no resistance to the Japanese, but because of the poor state of communications some Chinese commanders did order their troops into action. Either way, within five months of the so-called ‘Mukden Incident’ all of Manchuria was under Japanese occupation, and a hesitant Chinese resistance had been swept aside.

Ishii’s most helpful mentor was Colonel Chikahiko Koizumi. The much older Koizumi had been involved in chemical warfare research since 1918, and he soon realised that he and Ishii shared the same vision of using chemical and BW weapons to further Japan’s nationalistic goals abroad. Koizumi was very well connected with the army’s top brass and counted future Japanese Prime Minister and Minister of War Hideki Tojo among his closest friends. In 1930 Koizumi tried to persuade the High Command to reinstitute the army’s chemical weapons programme which had been suspended since Japan signed the Geneva Convention in 1925. That same year, he managed to have Ishii promoted to major and made chairman of the department of immunology at Tokyo Army Medical College.

Away from his training and lecturing duties, Ishii and a small team of fellow scientists began to privately culture lethal bacilli in their laboratory, such as bubonic plague, cholera, typhoid an...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 - The Seeds of Death

- Chapter 2 - Paris of the Orient

- Chapter 3 - Blood Harvest

- Chapter 4 - The Camp

- Chapter 5 - Forced Labour

- Chapter 6 - Guinea Pigs

- Chapter 7 - Precedents and Paper Trails

- Chapter 8 - Flamingo

- Chapter 9 - Reaping the Whirlwind

- Chapter 10 - Operation ‘PX’

- Chapter 11 - Dark Harvest

- Conclusion

- Appendix A - British Prisoners-of-War, Mukden Camp

- Appendix B - Some Key Characters

- Appendix C - Japanese Army Chemical and Biological Warfare Units

- Appendix D - Asia-Pacific War Timeline

- Notes

- Index