![]()

Chapter One

In the Beginning

For the early humans the sky and the sea must have been a confusing and threatening part of their lives. On a clear night there would be the myriad stars moving in the sky with perhaps the moon joining in, while in daylight the world would be dominated by the sun. On a cloudy day the clouds could present a constantly changing picture, sometimes passive and picturesque, while at other times threatening and dominating. There would be hourly and daily changes as well as the longer-term seasonal changes that would be reflected in the weather conditions and in the visibility. On the water the conditions could be equally changeable. The surface of the sea would reflect the strength and direction of the wind, but the picture could become confusing with local changes in conditions depending on the depth of the water and other factors. In many parts of the world the water level would rise up and down on a regular basis as the tides ebbed and flowed and this would also create currents.

When you think about the picture that was presented to early man it must have taken a long time to make some sense out of this confusion, particularly when there was not the means to record the constant changes. Many of the changes and events that were reflected by the visible changes that could be observed would be noted to take place on a regular basis, while others would appear quite random. Gradually patterns would have emerged such as the regular changes made by the tides and the rotation of the stars in the sky, but even these would have been challenging to identify because there was no easy way in which to measure time. The movement of the sun across the sky in daylight would have provided a guide to time, but even here the picture would have been confused with longer-term changes that occurred with the changes in the seasons. These seasonal changes would have been noted in the way that the weather changed over longer periods. Even today it can be a challenge to understand and be aware of the daily, monthly and annual changes in the weather, in the tides and in the movement of the heavenly bodies so without the deep understanding that we have now it must have taken ages to establish the intricate patterns of the natural world. However, it was the understanding of these patterns that formed the basis of early navigation techniques as man took to the sea for trade and for warfare.

Then early man had to take into consideration the short-term and largely unpredictable natural events. Today we understand all about rainbows but they must have presented a startling event to early man and it would be much the same with thunderstorms and violent squalls. Trying to make sense of all these natural events and to factor them into a means of navigating both on land and on the water must have been challenging and it is easy to see why they enlisted the help of the gods to explain some of these natural events. The gods would not change the weather, but at least they could provide an explanation. In the Mediterranean, which was one of the first places where man ventured out onto the sea, the conditions were more predictable than in many other parts of the world with negligible tides and currents and with winds that were reasonably predictable both on a daily and a seasonal basis. Under the influence of the sun the land heats up during the day, which can generate winds during the afternoons in quite a reliable fashion. The winter months are noticeably the time for bad weather in the Mediterranean and reports about the early navigation of the seas in the Mediterranean suggest that it was mainly carried out only in the more settled conditions of the summer months.

From this it can be seen that early navigation was largely dictated by the weather and particularly by the wind direction as the primitive sailing systems only allowed the craft to sail downwind. What was noticeable about these early navigators was that they were not under any of the time pressures that we see today and the navigation techniques reflected this. Navigation was largely visual, sailing along a coastline when the wind was favourable and then beaching or anchoring the craft at night when the visual navigation information disappeared. In much of the Mediterranean there is relatively deep water close inshore and there are fewer of the off-lying dangers such as rocks and shoals that are found in other parts of the world. This meant that visual navigation was a valid technique and when there might have been doubt about what dangers there were underwater then a sounding pole was used as a guide to the shallow water that might be found in river estuaries or when beaching.

So with these relatively benign conditions it is not surprising that the Mediterranean was one of the cradles of early navigation, but it was possible that this reputation was enhanced because this was one of the regions where writing and recording events was developed so the history of some early voyages has been recorded in words and drawings. Compare this with waters outside the Mediterranean such as northern Europe where very different conditions prevailed. Here you can find tides with the sea level rising and falling, and with those tides there can be tidal currents which in turn can generate offshore shallows and sandbanks. The rise and fall of the tide could have made places accessible when the tide was high and where most of the ports would dry out at low water. The currents generated by the movement of the whole body of water as the tide ebbed and flowed would have been both a benefit and a handicap to the early navigator, helping to carry him to his destination when the current was favourable and slowing him when it was not.

To add to the challenges of navigating in northern European waters was the much more unpredictable weather and areas of offshore rocks and shoals, both of which were hazards for the unwary sailor. Records of early techniques for sailors in northern waters are virtually non-existent and the development of sea-going vessels was considerably slower than in the Mediterranean, although when the Romans sailed their sea-going craft northwards across the Bay of Biscay they did find well-developed sea-going craft being used. What is interesting is that the records of the Roman voyages into northern waters makes little mention of the tides and currents that would have a significant effect on navigation in these waters. While the winds would have helped progress when they were favourable, it does seem likely that the tidal currents would have had a significant impact and you have to wonder if the techniques used on the River Thames for handling barges without motor or sails were used in the open seas. Even seventy years ago the bargees on the Thames would drift downstream using just the current for progress and guiding the barge which had no engine or sails into the desired berth or alongside other barges using a steering oar. When the current flowed upstream the reverse procedure could be used and this was a highly-developed skill that might have been used to good effect in inshore waters, although the craft used are likely to have had sail assistance as well and possibly also had propulsion by oars.

There seems little doubt that navigators in these northern waters needed a higher level of skill to cope with the challenging conditions, which of course would be the reason why the development of sea trade was a slower process. However, the Romans did report that they found local sea-going craft making voyages across the English Channel. The reports by the Romans take us to a point in history a little over 2,000 years ago and what we are missing is where and how navigation developed prior to the Romans coming onto the scene. It is likely that it was line-of-sight navigation similar to that used in the Mediterranean but with the added complication of using the currents to help progress. With the narrowest part of the English Channel at the Dover Straits enabling a visual sighting of the other side, it seems highly likely that the early navigators could roam far and wide using just visual navigation with two-way traffic across the Channel. The cultural and language similarities between the peoples of Brittany, the English West Country and Ireland suggest that early navigators were making voyages between these areas.

There is every reason to believe that the same sort of development took place in the Middle East and the Far East, but the evidence of navigation is well hidden. In the Pacific there is a long tradition of open ocean voyages using basic navigation techniques using natural indicators. These techniques have been in use up until recent times and the navigation technology has been well researched, leading to speculation that the Polynesians were well ahead of the game when it came to navigation. Because the Pacific is a series of islands rather than large land masses, the navigation techniques were specific to that region and you get the impression that in other parts of the world navigation developed using basic line-of-sight techniques that to a certain extent we still use today in familiar waters under what is termed pilotage navigation.

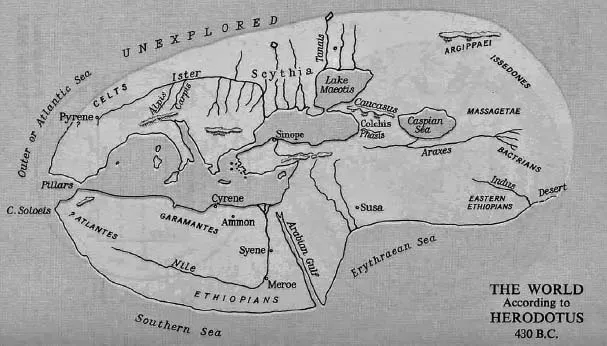

A very early ‘map’ based around the known areas of the Mediterranean.

Perhaps we should look at the types of boats that were developed in the various regions to give us a clue about navigation. The types of boat discovered buried and preserved mainly in riverbanks and sometimes used for ceremonial burials are relatively unseaworthy, which would suggest that they were used in the calmer waters inshore and probably first in rivers and then moving out to estuaries before venturing onto the open seas. Using dug-out canoes and similar basic craft, the occupants might have been more concerned with staying afloat than with navigation. With many settlements located along riverbanks, the first ventures on the water are likely to have been to cross the river, which is line-of-sight navigation. As more seaworthy boats were developed so it seems possible that the voyages became more adventurous, but in assuming this it is necessary to find a reason for such voyages. In the Middle East and the Mediterranean we know that voyages were untaken to find cargoes of exotic spices and similar valuable commodities and it is possible that this was the case in other parts of the world. Some metals such as Cornish tin were valuable commodities and their transport could have spurred more adventurous voyages. Fishing was another possibility for venturing out onto open sea waters.

The reasons for developing more capable craft and for venturing further afield may be hard to define without written records, but the navigation techniques used were likely to be visual which tended to mean navigating in daylight. If you head for the next headland you have a visual reference to steer by, which could account for the term ‘headland’. You also want to know what is underwater and the very simple sounding pole was used to dip the water over the bow to determine what was underneath. Dipping with a pole like this might not give you too much of a clue but it could at least tell you if the water was getting shallower or deeper. Small craft have been using similar visual techniques to navigate along a coastline up until recent times, backed up by other clues as and when it was possible. Of course these modern navigators had the benefit of a chart that could give them reassurance about the dangers that might be lurking below the surface.

A few years ago we went right back to basics when navigating in fog. Our aim was to round the Lizard Point where there is a line of rocks stretching for a couple of miles offshore. These are dangerous waters with strong tides so we had the idea of closing the rocks close inshore where they were very visible to see if we could find a way through the rocks in our small RIB (Rigid Inflatable Boat) with its shallow draft. In the calm foggy conditions this was a feasible solution and we closed the towering rocks just off the headland and headed for the gaps. The water here was clear and in the calm we could see the bottom so we headed for a gap and with two crew peering into the depths over the bow we found a way through without touching bottom. Purists might argue that this was a dangerous way to navigate but it worked and saved us a long journey offshore in the fog. As a navigator, there is nothing quite like being able to see the dangers so you can find a way around them. This could have been a valid way to navigate for those early navigators in the clear waters of the Mediterranean where sight plus the sounding stick could have provided a sort of solution.

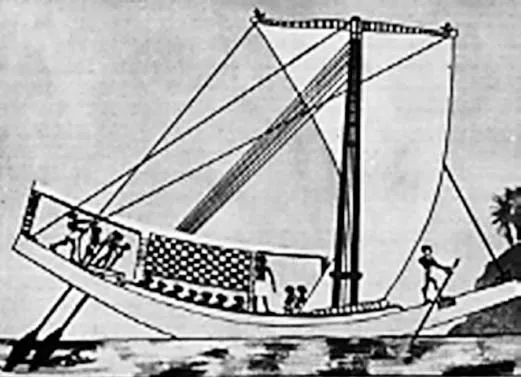

Very basic boats in which navigation would be entirely by visual signs.

The problem with just relying on seeing the bottom of the sea and sounding with a stick is that it only tells you what is happening directly underneath the craft. If the water is too shallow then the vessel is probably in trouble by the time it is discovered and this type of navigation just gives information in the very short term. A longer-distance solution to navigation might be found by reading the surface of the sea and this can produce some useful answers to help avoid danger. The surface of the sea tends to reflect the sky so at any distance from the vessel it is not possible to see through these surface reflections. However, if there is shallow water or perhaps a patch of rocks ahead it may be possible to see their location by the disturbance in the water surface. If there is a swell in the water or waves then this may create an area of breaking waves over the shallow water and if there is a tide or current running then there could also be a local area of disturbance over the shallows.

The sounding pole being used by the crew on the right was the earliest navigation ‘instrument’.

I used this effect about thirty years ago when we were trying to set a new record across the Atlantic. After leaving New York the large ships keep out to sea to avoid the extensive Nantucket Shoals. With our shallow draft I wanted to keep close inshore which would shorten the distance by about 100 miles. However, this meant heading across these changing areas of shallows and they had not been surveyed for more than thirty years so the depths shown on the chart could not be guaranteed. Should we take the risk of the short cut or should we play it safe by going outside? I decided to take the risk of going over the shallows on the basis that if there was dangerous shallow water then we would see the breaking waves that the swell coming in from the ocean would create. It was a high-risk gamble because our project was very high-profile and the world was watching but we broke the existing record by just two hours which was the time we saved by going across the shoals. We did see some areas of breaking waves and were able to avoid them, and this could have been similar to the techniques that ancient navigators used when voyaging along a coastline.

When the waters are tidal, any dangers that are underwater at high tide can be exposed at low tide. Early navigators may have started their explorations in the rivers where they had their settlements. Even if they were not tidal waters, rivers’ levels would rise and fall depending to a large extent on rainfall or perhaps melting snows further inland. This rise and fall of the water level would have helped to expose dangers and perhaps allow the early navigators to plot a visual route. These are the techniques perhaps used on the Nile and the Rhône, large rivers that exit to the Mediterranean which is non-tidal. Outside the Mediterranean where the seas are mainly tidal the rise and fall of the tide would have exposed sandbanks and rocks every few hours so a navigator could perhaps have anchored over low water and seen the dangers and then got under way when the waters rose. The navigators would have also been aware of the flow of the current and could have used that to make progress in a desired direction. The same techniques could have been used along coastlines and we have to remember that, unlike with the navigators of today, there was little or no pressure of time so they could wait for the right conditions to make progress in the desired direction.

In the absence of any instruments for measurement or guidance about direction, those early navigators would have been reliant mainly on the signs from nature, the seas and the skies. The skies would have been an indicator mainly about the weather and a skilled navigator would have been able to interpret the clouds and prevailing conditions to give an indication of what conditions might be like in the short term ahead. The wind direction could determine in which direction progress might be possible and the signs from the sea and the coastline could indicate dangers. We have to rely mainly on speculation about the navigation skills of early navigators and the skills that were required have been largely lost as we now have the luxury of accurate charts, weather forecasts over the radio and position-fixing of unheard-of accuracy. However, these luxuries could lure us into a false sense of security and the signs and skills used by the early navigators can still give useful warnings and indications of danger as a back-up for the modern systems. You ignore the signs of nature at your peril when navigating.

![]()

Chapter Two

Over the Horizon

Even in the early days of navigation as detailed in the previous chapter, there were vessels that had to find their way back to shore either because they had been blown away from the land by storms or because they were skippered by more adventurous seamen who had decided to undertake voyages away from the coastal routes. The more you delve into the history of navigation, the more you find that there were navigators who were prepared to undertake voyages where the outcome was far from a foregone conclusion, where they were heading over the horizon without knowing what lay beyond that great divide. Long before Columbus made his epic voyage of discovery across the Atlantic and going back thousands of years, we find that there are records of voyages made over the open ocean. These must have been the ultimate adventure: undertaking a voyage without knowing what the outcome might be. What is fascinating about the voyages is not only the excitement of discovery, but the navigation techniques that were used.

Those early ocean navigators must have been great observers of nature because they record many techniques that would signify the nearness of land. The movement of the sea can change significantly as the oceans grow shallower, there are birds and sea life that are only found close to land and clues such as patches of seaweed would all point to the possibility of land being close over the horizon. Following these clues to the possibility of land that was out of sight but within close sailing distance wa...