- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The French Air Force in the First World War

About this book

The French air force of the First World War developed as fast as the British and German air forces, yet its history, and the enormous contribution it made to the eventual French victory, is often forgotten. So Ian Sumner's photographic history, which features almost 200 images, most of which have not been published before, is a fascinating and timely introduction to the subject. The fighter pilots, who usually dominate perceptions of the war in the air, play a leading role in the story, in particular the French aces, the small group of outstanding airmen whose exploits captured the publics imagination. Their fame, though, tends to distract attention from the ordinary unremembered airmen who formed the body of the air force throughout the war years. Ian Sumner tells their story too, as well as describing in a sequence of memorable photographs the less well-known branches of the service the bomber and reconnaissance pilots and the variety of primitive warplanes they flew.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The French Air Force in the First World War by Ian Sumner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

‘… difficult, dangerous, at times impossible’

A fter a decade of hectic development, the French air service was able to take the field in August 1914 with a substantial force of 132 aircraft divided between twenty-five squadrons. Numbers, however, told only half the story. The early years of the service had been, and still were, bedevilled by controversy, as engineers and artillery disputed the purpose of the new machines and vied for their control.

Already responsible for military ballooning, the engineers were first out of the blocks, making an abortive trip to Ohio in 1906 to negotiate the purchase of several Wright Flyers. By then, however, French manufacturers were also up and running, offering machines more powerful and stable than their American counterparts and equipped with wheels instead of skids. In August 1909, at Bétheny (Marne), the first international air meeting attracted a wide range of planes and pilots, as well as huge crowds of enthusiastic onlookers. Among them were a group of army officers, there to evaluate the machines on show, and within weeks five planes had been purchased for the engineers to create a military aviation service. The artillery fought back at once: the obvious purpose of the new technology, they argued, was spotting for the guns. In response, a separate artillery aviation section was created at Vincennes, where a research team soon began to investigate all aspects of military flying: shellspotting, reconnaissance, bombing and armament.

From 1910 the new machines took part in the annual autumn manoeuvres, demonstrating their value in reconnaissance and shell-spotting, as well as the benefits of equipping each squadron with a single aircraft type. The aircraft themselves, however, remained embryonic. A competition in September 1911 promised huge cash prizes and guaranteed government orders to the winners, but only sixteen of the seventy-one entrants survived the preliminary round. Engines as yet lacked the power to lift the specified 300kg load, and the final rankings were determined largely by speed. Heavy and hard to handle, most soon proved unfit for active service.

In 1912, the air service was formally recognized as a branch of the engineers, and the following year it joined the balloon service to form a fifth department within the army, equal in status to the infantry, cavalry, engineers and artillery. Yet the interdepartmental conflict continued to rage, and in August 1913 the artillery gained the upper hand. General Félix Bernard, the first director of aviation, was a gunner utterly blind to his new command. Aircraft, he opined, were useful only for shell-spotting ‘whenever telegraph wires prevent the raising of a captive balloon’. In his ignorance and mistrust of the new machines, however, Bernard was only too typical of his peers. Just a handful of senior officers had any experience of working with aircraft, and when the Germans invaded in August 1914 few commanders were prepared to trust the intelligence gathered by the many French reconnaissance missions flown.

Later that month, with the enemy nearing Paris, one crew spotted the German First Army change its direction of march – but the corps commander simply refused to believe them. Only when the information reached General Joseph Gallieni, commander of the Paris garrison – the Camp Retranche de Paris (CRP) – did it provoke a reaction, allowing the French to halt the invader on the Marne. Nor, in the confusion of the retreat, did aircraft have much opportunity to contribute as shell-spotters. Air combat, however, soon featured. Pilots and observers started to carry personal weapons straight away – in self-defence as well as to cripple their opponents – and on 5 October 1914, flying a Voisin 3 equipped with a jury-rigged machine gun, pilot Joseph Frantz (V24) and observer Louis Quenault shot down an enemy aircraft, recording the first confirmed victory in air-to-air combat.

Struggling to find a role, the air service was also desperately short of personnel. Confident the war would be short and pilots unnecessary, in August 1914 the hapless Bernard had closed the military flying schools and returned all current trainees to their regiments. Within weeks the army was scouring its ranks for volunteer aircrew, ideally men with a technical background, although in 1915 many former cavalry officers also transferred successfully. The pre-war schools were reopened and new schools added. Here aspiring pilots earned their wings, attending lectures on flight, putting theory into practice in a series of increasingly powerful machines, then finally going solo. Qualified pilots eventually progressed to a number of specialist schools, located particularly in south and south-west France, where they could train on particular aircraft types. Only then were they sent to the pool – the Groupe de Divisions d’Entraînement (GDE), situated in and around Le Plessis-Belleville (Oise), north of Paris – to await their posting to a front-line squadron.

Observers and bomb-aimers, recruited primarily among artillerymen to profit from their technical skills and knowledge, followed a different route. A specialist school was established at Le Plessis-Belleville, but qualified artillery observers were deemed to need little extra training. They were quickly posted to a squadron and could be operational very shortly afterwards.

Paris, 2013. Designed by Clément Ader (1841–1925), inveterate inventor and champion of air power, this steam-powered flying machine – Avion III – hangs proudly in the Musée des Arts et Métiers. Although Avion left the ground on its maiden flight in 1897, its pilot was never in full control of his craft. The steam engine also proved a dead end, but Ader left a permanent legacy in his coinage ‘avion’, which was adopted for official use in 1911 before being absorbed into the wider French language to replace the Anglophone ‘aéroplane’.

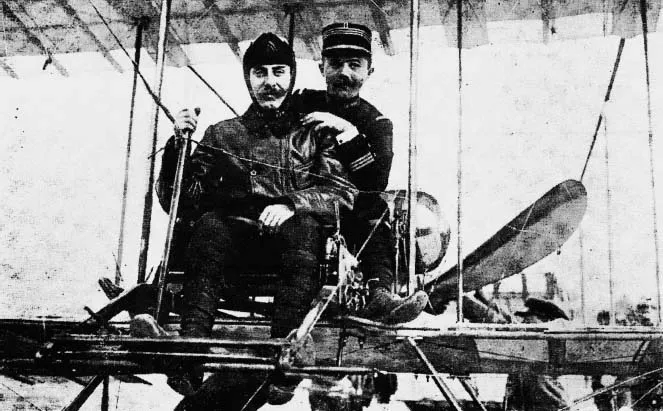

Vincennes (Val-de-Marne), 9 June 1910. Lieutenant Albert Féquant (1886–1915) and Captain Charles Marconnet (1869–1914) are seated in their Farman, shortly after breaking the world distance record by covering 158km from Mourmelon (Marne) to Vincennes in 2.5 hours. This ground-breaking flight opened military eyes to the range, payload and potential of the new machines. The Farman made no real provision for a passenger, so Marconnet had to wedge himself in as best he could. Although a qualified pilot, he returned to 45th Infantry in 1914 and was killed in action at Carnoy (Somme) on 27 November. Féquant (VB102) remained in aviation, primarily in bomber units; he was killed returning from a long-distance raid on Saarbrücken on 6 September 1915.

Belfort (Territoire de Belfort). Admiring soldiers crowd around a Voisin biplane on the Champ de Mars. Captain Ferdinand Ferber (1862–1909) made the first flight from this key frontier fortress town (perhaps that depicted here) in July 1909. An artilleryman, aviation pioneer and correspondent of the Wright brothers, Ferber never designed a viable aircraft, but his example encouraged many others. He died in a flying accident at Beuvrequen (Pas-de-Calais) in September 1909. Belfort acquired a permanent landing ground in August 1912, home on the outbreak of war to two Blériot squadrons, BL3 and BL10.

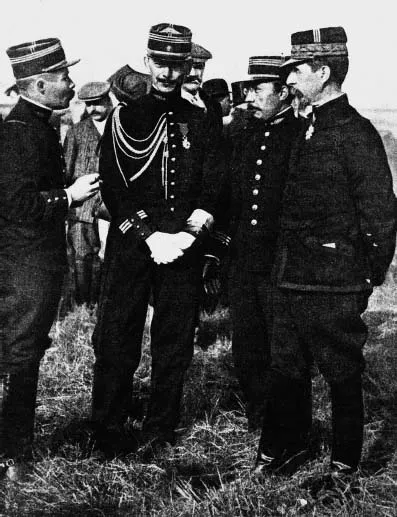

Buc (Yvelines), 29 May 1911. Pictured (right to left) are General Pierre Roques (1856–1920), Captain Do Hûu Vi (1883–1916), Captain Félix Marie (1870–1938) and Captain Charles Marconnet. A notably energetic inspector of aviation from 1910 to 1912, Roques did much to prepare French aircraft and balloons for war. After transferring to a divisional command, he rose via XII Corps and First Army to become minister of war in 1916. Marie served as aviation commander of First Army in Alsace, and on the aviation staff. The Vietnamese Do served in Morocco, and with GB1. Seriously injured in a crash in 1915, he returned to his regiment, 1st Foreign Legion, but was killed on 9 July 1916, leading 7th Company in an attack at Belloy-en-Santerre (Somme).

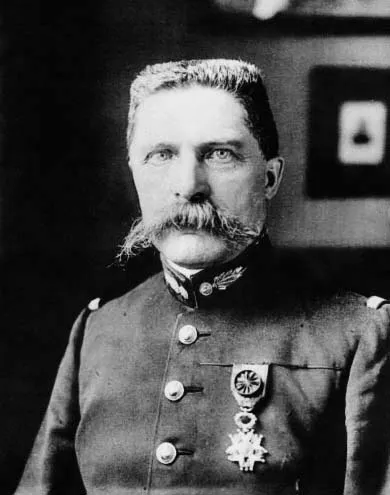

General Édouard Hirschauer (1857–1943). An engineer and previously commander of the balloon service, Hirschauer was appointed inspector of aviation in April 1912. The lethargy of aircraft manufacturers frustrated his plans to expand the air service, and the rival artillery – coveting the aviation budget – accused him of collusion, forcing his resignation in August 1913. Fourteen months later Hirschauer returned as director of aviation, replacing General Félix Bernard (1857–1939) and doing much to put French manufacturers on a war footing. But again he was made a scapegoat – blamed for the vulnerability of French machines to the new Fokker Eindecker – and in September 1915 he was sacked. Hirschauer went on to serve with front-line formations, taking command of Second Army in December 1917. He ended his career as a politician, serving several terms as a senator for the Moselle.

Autumn manoeuvres, Sainte-Maure (Indre-et-Loire), September 1912. Piloted by Lieutenant Antonin Brocard (1885–1960), a Deperdussin TT of D6 lands at a temporary airfield. Brocard was appointed CO in March 1915 of MS/N3, then in 1916 of the celebrated Groupement de Cachy, later made permanent as GC12. In mid-1916, he chose a stork (cigogne) as the insignia of N3, and the bird was soon adopted in different variants by all the squadrons of GC12, which henceforth became known by that name. In 1917 he took a staff post as technical advisor to the recently appointed under-secretary of state, Jacques-Louis Dumesnil. The opposing forces in the 1912 manoeuvres, commanded by General Gallieni and General Marion, together deployed some 100,000 men and seventy-two aircraft. Each force comprised four squadrons, including the first five squadrons (Nos 1 to 5) of the newly independent air service, plus a number of scratch units.

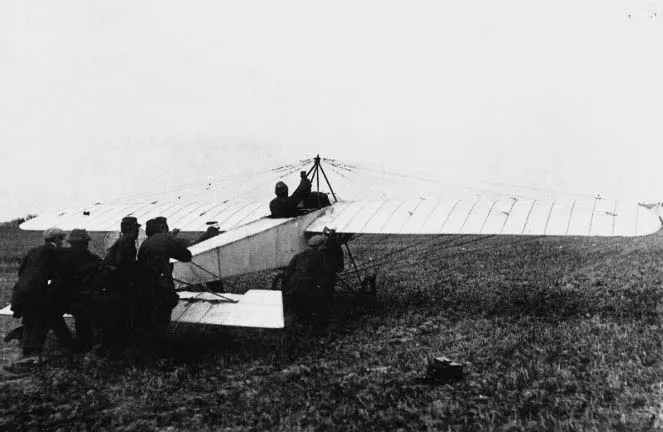

Autumn manoeuvres, south-west France, September 1913. Ignoring a line of sentries, curious bystanders have managed to get close to the new machines, as soldiers and spectators combine to push a Blériot monoplane into the wind for take-off. During the manoeuvres, Red Force (including squadrons BL3, MF5 and HF19, plus the dirigible Fleurus) opposed Blue Force (including squadrons D6, V21 and BR17, plus the dirigible Adjudant-Vincenot).

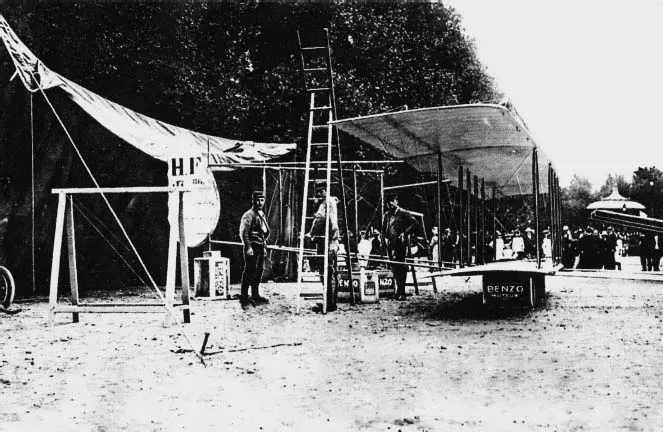

Autumn manoeuvres, south-west France, September 1913. Preparing for the off, mechanics from HF19 reassemble a Henri Farman H.F.20, propped against cases of Benzol engine oil. Although aircraft had been included in these major exercises since 1910, the four-year cycle of manoeuvres and the lack of large-scale training facilities left many senior officers dangerously short of practical experience of working with the new technology.

Near Kasbah Tadla, Morocco, Jun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One ‘… difficult, dangerous, at times impossible’

- Chapter Two Nailed to the sky

- Chapter Three Giving them something to think about

- Chapter Four The crucible of the service

- Chapter Five Gothas by day, Zeppelins by night

- Chapter Six Fit for service

- Chapter Seven On to victory