- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

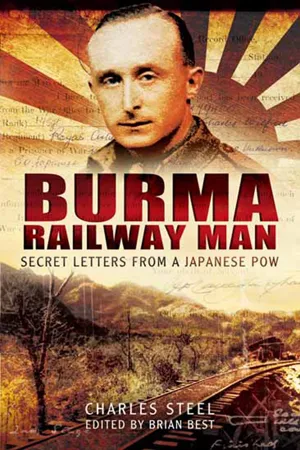

Charles Steel took part in two military disasters - the Fall of France and the Dunkirk evacuation, and the Fall of Singapore. Shortly before the latter, he married Louise. Within days of being captured by the Japanese, he began writing a weekly letter to his new bride as means of keeping in touch with her in his mind, for the Japanese forbade all writing of letters and diaries. By the time he was liberated 3 1/2 years later, he had written and hidden some 180 letters, to which were added a further 20 post-liberation letters. Part love-letter, part diary these unique letters intended for Louise's eyes only describe the horror of working as a slave on the Burma - Siam Railway and, in particular, the construction of the famous Bridge over the River Kwai. It is also an uplifting account of how man can rise above adversity and even secretly get back at his captors by means of 'creative accounting'!. Now, we can share the appalling and inspiring experiences of this remarkable man.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Burma Railway Man by Charles Steel, Brian Best in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

| Acknowledgments | |

| Introduction | |

| 1 | The Early Years |

| 2 | The Fall of France |

| 3 | Changes |

| 4 | Another Military Defeat |

| 5 | ‘Phoney’ Captivity |

| 6 | The Impossible Project |

| 7 | Bridge Over the River Kwai |

| 8 | ‘Speedo’ |

| 9 | Return to Nong Pladuk |

| 10 | Bombed by the RAF |

| 11 | Ubon |

| 12 | Liberation |

| 13 | Home at Last! |

| Postscript | |

| Bibliography | |

| Index |

Acknowledgments

When I was asked if I was interested in editing the letters kept by a prisoner of the Japanese, my initial reaction was that the subject matter would be both grim and depressing. I am glad I did not turn down the project, for I found in the letters of Charles Steel one of the most uplifting reading experiences I have ever enjoyed.

For this, I am grateful to Margaret and David Sargent for putting their trust in me and allowing full access to all of Charles and Louise Steel’s papers.

I must also thank the staffs at the Imperial War Museum Library and Crowborough and Tunbridge Wells Libraries for their help and suggestions.

Introduction

Charles Steel had a most unfortunate war. He was one of the unlucky few who participated in two of the greatest disasters to befall the British Army – Dunkirk and the fall of Singapore. He not only survived both experiences but emerged mentally stronger and surprisingly unembittered. His story is well worth the telling, for he was a survivor of that most appalling experience that could befall a soldier captured during the Pacific War – he was held a prisoner of war by the Japanese.

For four long years he and his fellow prisoners endured cruelties and hardships that are, today, almost beyond comprehension. Many men did not survive the harrowing experiences of starvation, disease, slave labour and the barbaric acts of their captors. Unable to cope with the nightmare into which they had been pitched, so many suffered mentally and just gave up as if preferring death to any faint hope of eventual salvation.

Steel was not one of these Muselmanner, the German slang for the ‘walking dead’, whose divine spark had been extinguished within. Instead, he refused to be paralysed by a denial of what was happening to him and set about adopting a goal he could focus upon. Something that would kindle a fighting spirit so he would be able to trudge through the darkness toward a far distant pinprick of light.

Within days of being captured at Singapore, Charles wrote his first letter to Louise, his wife of just ninety days. From the chaos of that debacle, when he felt sure they would be shortly repatriated, Charles began writing letters that were never sent. Even when he was at his lowest ebb, a sick, starved slave on the Burma-Siam railway, he kept writing to his beloved Louise, relating not only the everyday horrors but also his observations of his captors, his fellow POWs, the surrounding countryside and wildlife. Above all, the letters were declarations of love written by a man who focused on his young wife as his personal reason to rise above the surrounding hopelessness and will himself to survive. Risking punishment – for the Japanese forbade any writing or sketching that would record their inhuman behaviour – Charles managed to document life as a slave labourer on one of the most remarkable engineering feats of the twentieth century. The letters were a form of record, but written for Louise’s eyes – only and with no thought that they would be read by a curious posterity.

Steel wrote and hid 183 letters during captivity and another thirty-two after the Japanese surrender. They show a man who retained his sanity, humanity and even a sense of humour under the most testing of circumstances. Far from being a broken man, he put his experiences behind him and made his dreams during captivity come true.

Chapter 1

The Early Years

My Dear WifeI am a Prisoner of War.

These stark opening words written from Changi, just after the fall of Singapore, were the first of nearly 200 letters written, but never sent, by Battery Sergeant Major Charles Steel. They were written when there seemed hope that he and his fellow captives might be exchanged and repatriated. This was the time of phoney captivity, when the Japanese left the British and Australians to their own devices and the only suffering was poor food, overcrowding and boredom. When Steel wrote that he was a prisoner of the Japanese, it did not have the fearful connotation it was soon to gain. Indeed, those British officers who were familiar with the Japanese Army during the 1920s and 1930s did not predict the dramatic change of behaviour towards their prisoners. It was pointed out that, during the war of 1904–05, the Japanese treated their Russian prisoners in an exemplary fashion.

In the meantime, Charles had plenty of time to recollect on the unkind fates that had directed him to his present predicament.

Charles Wilfred Steel was born on 7 December 1916 in a middle-class area of Bow in London’s East End. His father was a manager, who later rose to become a partner with the brokerage firm Mardorf, Peach in the Corn Exchange. The railway ran through a cutting below the bottom of his parent’s garden and one of Charles’s earliest recollections was of the steam trains that journeyed to and from Liverpool Street Station. This early fascination for steam engines remained with him for all his life.

Tragedy struck when his mother was one of the many thousands who succumbed to the flu pandemic of 1918 and it was left to her two spinster sisters to care for him. His father married his secretary and Charles’s new stepmother proved to be a loving substitute and soon provided Charles with a younger brother named Ken.

Charles was an academically bright child and in 1928 gained a scholarship to the Sir George Moneaux Grammar School in Walthamstow. Both the school and his father encouraged outdoor pursuits and physical fitness, something for which Charles would later be thankful. When he was just seventeen, he left school having matriculated with seven subjects. He had a good head for figures and, with his father’s help, joined a firm of stockbrokers. It was a career in which he remained all his working life.

Once he had left school, the family moved from the East End to the comparatively rural area of Shirley, on the Kent/Surrey border, not far from Bromley. Charles immediately took to the whole ambience of working in the City and relished the opportunity of trading on the dealing floor at the Stock Exchange. One of the social activities available to City workers and, indeed was encouraged, was the joining of a Territorial Army regiment.

The most prestigious City regiment was the Honorable Artillery Company at Finsbury Square but, in 1937, Charles chose to join the 97 (Kent Yeomanry) Field Regiment Royal Artillery, 387th Battery, Queen’s Own West Kent Yeomanry, for it was based at Bromley Common, close to his home. Within a short time Gunner Steel had made a whole new circle of friends and took on new pursuits. One of the activities he enjoyed was to cycle around the lovely Kent countryside. In those pre-war days there was very little traffic and cycling clubs filled the roads most weekends. It was during one of these club outings that Charles noticed and was instantly attracted to a slim young lady who was happy to encourage his advances. Her name was Louise Crane and she lived at the nearby village of North Cray. They soon found they had many interests in common, including the part-time army. To Charles’s mild irritation, he found that his new girlfriend was a sergeant in the ATS and, throughout their respective service careers, she continued to outrank him.

The years between the wars were difficult for the Territorial Army. Lack of training grants and equipment, few experienced instructors and a general public apathy made the Territorials little more than a social club. The gathering war clouds and the passing of the Conscription Act of 1938 changed this with a large influx of volunteers. Unfortunately, the shortage of officers and experienced NCO’s seriously hampered training and organization. This was uncomfortably brought home during the annual TA camp and manoeuvres at Okehampton in the spring of 1939.

The previous summer, Charles had enjoyed a rather jolly time at his first camp on the South Downs near Seaford. In glorious summer weather, the young volunteers were put through gun drill, but there had been no firing of their vintage 18-pounder guns. Instead, there had be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents