- 574 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

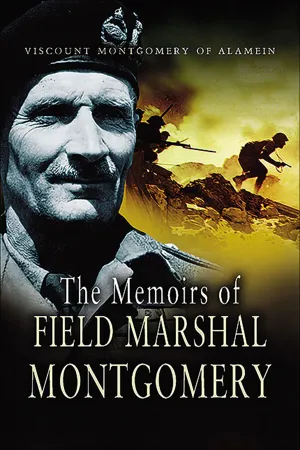

The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery

About this book

In his own words, the victor of El Alamein tells his life story in a book that's "an absolutejoy to read and may be described as a tour-de-force" (

Belfast News Letter).

First published in 1958 Montgomery's memoirs cover the full span of his career first as a regimental officer in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and then as a Staff Officer. His choice of the Warwickshires was due to his lack of money. He saw service in India before impressing with his courage, tactical skill and staff ability in the Great War. Despite his tactless uncompromising manner his career flourished between the wars but it was during the retreat to Dunkirk that his true brilliance as a commander revealed itself. The rest is history, but in this autobiography we can hear Monty telling his side of the story of the great North African Campaign followed by the even more momentous battles against the enemy "and, sadly, the Allies" as he strove for victory in North West Europe. His interpretation of the great campaign is of huge importance and reveals the deep differences that existed between him and Eisenhower and other leading figures. His career ended in disappointment and frustration being temperamentally unsuited to Whitehall and the political machinations of NATO.

First published in 1958 Montgomery's memoirs cover the full span of his career first as a regimental officer in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and then as a Staff Officer. His choice of the Warwickshires was due to his lack of money. He saw service in India before impressing with his courage, tactical skill and staff ability in the Great War. Despite his tactless uncompromising manner his career flourished between the wars but it was during the retreat to Dunkirk that his true brilliance as a commander revealed itself. The rest is history, but in this autobiography we can hear Monty telling his side of the story of the great North African Campaign followed by the even more momentous battles against the enemy "and, sadly, the Allies" as he strove for victory in North West Europe. His interpretation of the great campaign is of huge importance and reveals the deep differences that existed between him and Eisenhower and other leading figures. His career ended in disappointment and frustration being temperamentally unsuited to Whitehall and the political machinations of NATO.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

BOYHOOD DAYS

I WAS born in London, in St. Mark’s Vicarage, Kennington Oval, on 17th November 1887.

Sir Winston Churchill in the first volume of Marlborough, His Life and Times wrote thus about the unhappy childhood of some men: “The stern compression of circumstances, the twinges of adversity, the spur of slights and taunts in early years, are needed to evoke that ruthless fixity of purpose and tenacious mother-wit without which great actions are seldom accomplished.”

Certainly I can say that my own childhood was unhappy. This was due to a clash of wills between my mother and myself. My early life was a series of fierce battles, from which my mother invariably emerged the victor. If I could not be seen anywhere, she would say—“Go and find out what Bernard is doing and tell him to stop it.” But the constant defeats and the beatings with a cane, and these were frequent, in no way deterred me. I got no sympathy from my two elder brothers; they were more pliable, more flexible in disposition, and they easily accepted the inevitable. From my eldest sister, who was next in the family after myself, I received considerable help and sympathy; but, in the main, the trouble had to be suffered by myself alone. I never lied about my misdeeds; I took my punishment. There were obvious faults on both sides. For myself, although I began to know fear early in life, much too early, the net result of the treatment was probably beneficial. If my strong will and indiscipline had gone unchecked, the result might have been even more intolerable than some people have found me. But I have often wondered whether my mother’s treatment for me was not a bit too much of a good thing: whether, in fact, it was a good thing at all. I rather doubt it.

I suppose we were an average Victorian family. My mother was engaged at the age of fourteen and married my father in July 1881, when she was scarcely out of the schoolroom. Her seventeenth birthday was on the 23rd August 1881, one month after her wedding day. My father was then Vicar of St. Mark’s, Kennington Oval, and my mother was plunged at once into the activities of the wife of a busy London vicar.

Children soon appeared. Five were born between 1881 and 1889, in which year my father was appointed Bishop of Tasmania—five children before my mother had reached the age of twenty-five. I was the fourth. There was then a gap of seven years, when two more were born in Tasmania; then another gap of five years still in Tasmania, when another boy arrived. The last, my youngest brother Brian, was born after we had left Tasmania and were back in London.

So my mother bore nine children in all. The eldest, a girl, died just after we arrived in Tasmania, and one of my younger brothers died in 1909 when I was serving with my regiment in India. That left seven, and all seven are alive today.

As if this large family was not enough, we always had other children living with us. In St. Mark’s Vicarage in Kennington were three small boys, distant cousins, whose parents were in India. In Tasmania, cousins arrived from England who were delicate and needed Tasmanian air. In London after our return from Tasmania, there was always someone other than ourselves.

It was really impossible for my mother to cope with her work as the wife of a London vicar or as a Bishop’s wife, and also devote her time to her children, and to the others who lived with us. Her method of dealing with the problem was to impose rigid discipline on the family and thus have time for her duties in the parish or diocese, duties which took first place. There were definite rules for us children; these had to be obeyed; disobedience brought swift punishment. A less rigid discipline, and more affectionate understanding, might have wrought better, certainly different, results in me. My brothers and sisters were not so difficult; they were more amenable to the régime and gave no trouble. I was the bad boy of the family, the rebellious one, and as a result I learnt early to stand or fall on my own. We elder ones certainly never became a united family. Possibly the younger ones did, because my mother mellowed with age.

Against this curious background must be set certain rewarding facts. We have all kept on the rails. There have been no scandals in the family; none of us have appeared in the police courts or gone to prison; none of us have been in the divorce courts. An uninteresting family, some might say. Maybe, and if that was my mother’s object she certainly achieved it. But there was an absence of affectionate understanding of the problems facing the young, certainly as far as the five elder children were concerned. For the younger ones things always seemed to me to be easier; it may have been that my mother was exhausted with dealing with her elder children, especially with myself. But when all is said and done, my mother was a most remarkable woman, with a strong and sterling character. She brought her family up in her own way; she taught us to speak the truth, come what may, and so far as my knowledge goes none of her children have ever done anything which would have caused her shame. She made me afraid of her when I was a child and a young boy. Then the time came when her authority could no longer be exercised. Fear then disappeared, and respect took its place. From the time I joined the Army until my mother died, I had an immense and growing respect for her wonderful character. And it became clear to me that my early troubles were mostly my own fault.

However, it is not surprising that under such conditions all my childish affection and love was given to my father. I worshipped him. He was always a friend. If ever there was a saint on this earth, it was my father. He got bullied a good deal by my mother and she could always make him do what she wanted. She ran all the family finances and gave my father ten shillings a week; this sum had to include his daily lunch at the Athenaeum, and he was severely cross-examined if he meekly asked for another shilling or two before the end of the week. Poor dear man, I never thought his last few years were very happy; he was never allowed to do as he liked and he was not given the care and nursing which might have prolonged his life. My mother nursed him herself when he could not move, but she was not a good nurse. He died in 1932 when I was commanding the 1st Battalion The Royal Warwickshire Regiment in Egypt. It was a tremendous loss for me. The three outstanding human beings in my life have been my father, my wife, and my son. When my father died in 1932, I little thought that five years later I would be left alone with my son.

We came home from Tasmania late in 1901, and in January 1902 my brother Donald and myself were sent to St. Paul’s School in London. My age was now fourteen and I had received no preparation for school life; my education in Tasmania had been in the hands of tutors imported from England. I had little learning and practically no culture. We were “Colonials,” with all that that meant in England in those days. I could swim like a fish and was strong, tough, and very fit; but cricket and football, the chief games of all English schools, were unknown to me.

I hurled myself into sport and in little over three years became Captain of the Rugby XV, and in the Cricket XI. The same results were not apparent on the scholastic side.

In English I was described as follows:

| 1902 | essays very weak. |

| 1903 | feeble. |

| 1904 | very weak; can’t write essays. |

| 1905 | tolerable; his essays are sensible but he has no notion of style. |

| 1906 | pretty fair. |

Today I should say that my English is at least clear; people may not agree with what I say but at least they know what I am saying. I may be wrong; but I claim that I am clear. People may misunderstand what I am doing but I am willing to bet that they do not misunderstand what I am saying. At least they know quite well what they are disagreeing with.

After I had been three years at St. Paul’s my school report described me as backward for my age, and added: “To have a serious chance for Sandhurst, he must give more time for work.”

This report was rather a shock and it was clear I must get down to work if I was going to get a commission in the Army. This I did, and passed into Sandhurst half-way up the list without any difficulty. St. Paul’s is a very good school for work so long as you want to learn; in my case, once the intention and the urge was clear the masters did the rest and for this I shall always be grateful. I was very happy at St. Paul’s School. For the first time in my life leadership and authority came my way; both were eagerly seized and both were exercised in accordance with my own limited ideas, and possibly badly. For the first time I could plan my own battles (on the football field) and there were some fierce contests. Some of my contemporaries have stated that my tactics were unusual and the following article appeared in the School magazine in November 1906. I should explain that my nickname at St. Paul’s was Monkey.

OUR UNNATURAL HISTORY COLUMAN

No. 1—The Monkey

“This intelligent animal makes its nest in football fields, football vests, and other such accessible resorts. It is vicious, of unflagging energy, and much feared by the neighbouring animals owing to its unfortunate tendency to pull out the top hair of the head. This it calls ‘tackling.’ It may sometimes be seen in the company of some of them, taking a short run, and, in sheer exuberance of animal spirits, tossing a cocoanut from hand to hand! To foreign fauna it shows no mercy, stamping on their heads and twisting their necks, and doing many other inconceivable atrocities with a view, no doubt, to proving its patriotism.

To hunt this animal is a dangerous undertaking. It runs strongly and hard, straight at you, and never falters, holding a cocoanut in its hand and accompanied by one of its companions. But just as the unlucky sportsman is expecting a blow, the cocoanut is transferred to the companion, and the two run past the bewildered would-be Nimrod.

So it is advisable that none hunt the monkey. Even if caught he is not good eating. He lives on doughnuts. If it is decided to neglect this advice, the sportsman should first be scalped, so as to avoid being collared.”

I had little pocket money in those days; my parents were poor; we were a large family; and there was little spare cash for us boys. But we had enough and we all certainly learnt the value of money when young.

I was nineteen when I left St. Paul’s School. My time there was most valuable as my first experience of life in a larger community than was possible in the home. The imprint of a school should be on a boy’s character, his habits and qualities, rather than on his capabilities whether they be intellectual or athletic. In a public school there is more freedom than is experienced in a preparatory or private school; the danger is that a boy should equate freedom with laxity. This is what happened to me, until I was brought up with a jerk by a bad report. St. Paul’s left its imprint on my character; I was sorry to leave, but not so sorry as to lose my sense of proportion. For pleasant as school is, it is only a stepping stone. Life lies ahead, and for me the next step was Sandhurst. “When I became a man, I put away childish things”—some of them, anyway.

And so I went to Sandhurst in January 1907.

Looking back on their boyhood, some people would no doubt be able to suggest where things might have been changed for the better. Briefly, in my own case, two matters cannot have been right: both due to the fact that my mother ran the family and my father stood back. First, I began to know fear when very young and gradually withdrew into my own shell and battled on alone. This without doubt had a tremendous effect on the subsequent development of my character. Secondly, I was thrown into a large public school without having had certain facts of life explained to me; I began to learn them for myself in the rough and tumble of school life, and not finally until I went to Sandhurst at the age of nineteen. This neglect might have had bad results; but luckily, I don’t think it did. Even so, I wouldn’t let it happen to others.

When I went to school in London I had learnt to play a lone hand, and to stand or fall alone. One had become self-sufficient, intolerant of authority and steeled to take punishment.

By the time I left school a very important principle had just begun to penetrate my brain. That was that life is a stern struggle, and a boy has to be able to stand up to the buffeting and set-backs. There are many attributes which he must acquire if he is to succeed: two are vital, hard work and absolute integrity. The need for a religious background had not yet begun to become apparent to me. My father had always hoped that I would become a clergyman. That did not happen and I well recall his disappointment when I told him that I wanted to be a soldier. He never attempted to dissuade me; he accepted what he must have thought was the inevitable; and if he could speak to me today I think he would say that it was better that way. If I had my life over again I would not choose differently. I would be a soldier.

CHAPTER 2

MY EARLY LIFE IN THE ARMY

IN 1907 entrance to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, was by competitive examination. There was first a qualifying examination in which it was necessary to show a certain minimum standard of mental ability; the competitive examination followed a year or so later. These two hurdles were negotiated without difficulty, and in the competitive examination my place was 72 out of some 170 vacancies. I was astonished to find later that a large number of my fellow cadets had found it necessary to leave school early and go to a crammer in order to ensure success in the competitive entrance examination.

In those days the Army did not attract the best brains in the country. Army life was expensive and it was not possible to live on one’s pay. It was generally considered that a private income or allowance of at least £100 a year was necessary, even in one of the so-called less fashionable County regiments. In the cavalry, and in the more fashionable infantry regiments, an income of up to £300 or £400 was demanded before one was accepted. These financial matters were not known to me when I decided on the Army as my career; nobody had explained them to me or to my parents. I learned them at Sandhurst when it became necessary to consider the regiment of one’s choice, and this was not until about halfway through the course at the college.

The fees at Sandhurst were £150 a year for the son of a civilian and this included board and lodging, and all necessary expenses. But additional pocket money was essential and after some discussion my parents agreed to allow me £2 a month; this was also to continue in the holidays, making my personal income £24 a year.

It is doubtful if many cadets were as poor as myself; but I managed. Those were the days when the wrist watch was beginning to appear and they could be bought in the College canteen; most cadets acquired one. I used to look with envy at those watches, but they were not for me; I did not possess a wrist watch till just before the beginning of the war in 1914. Now I suppose every boy has one at the age of seven or eight.

Outside attractions being denied to me for want of money, I plunged into games and work. On going to St. Paul’s in 1902, I had concentrated on games; now work was added, and this was due to the sharp jolt I had received on being told the truth about my idleness at school. I very soon became a member of the Rugby XV, and played against the R.M.A., Woolwich, in December 1907 when we inflicted a severe defeat on that establishment.

In the realm of work, to begin with things went well. The custom then was to select some of the outstanding juniors, or first term cadets, and to promote them to lance-corporal after six weeks at the College. This was considered a great distinction; the cadets thus selected were reckoned to be better than their fellows and to have shown early the essential qualities necessary for a first class officer in the Army. These lance-corporals always became sergeants in their second term, wearing a red sash, and one or two became colour-sergeants carrying a sword; colour-sergeant was the highest rank for a cadet.

I was selected to be a lance-corporal. I suppose this must have gone to my head; at any rate my downfall began from that moment. The Junior Division of “B” Company, my company at the College, contained a pretty tough and rowdy crowd and my authority as a lance-corporal caused me to take a lead in their activities. We began a war with the juniors of “A” Company who lived in the storey above us; we carried the war into the areas of other companies living farther away down the passages. Our company became known as “Bloody B,” which was probably a very good name for it. Fierce battles were fought in the passages after dark; pokers and similar weapons were used and cadets often retired to hospital for repairs. This state of affairs obviously could not continue, even at Sandhurst in 1907 when the officers kept well clear of the activities of the cadets when off duty.

Attention began to concentrate on “Bloody B” and on myself. The climax came when during the ragging of an unpopular cadet I set fire to the tail of his shirt as he was undressing; he got badly burnt behind, retired to hospital,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Yet man...

- Contents

- Maps and Diagrams

- List of Photographs

- Foreword

- 1. Boyhood Days

- 2. My Early Life in the Army

- 3. Between the Wars

- 4. Britain Goes to War in 1939

- 5. The Army in England After Dunkirk

- 6. My Doctrine of Command

- 7. Eighth Army

- 8. The Battle of Alam Halfa

- 9. The Battle of Alamein

- 10. Alamein to Tunis

- 11. The Campaign in Sicily

- 12. The Campaign in Italy

- 13. In England Before D-Day

- 14. The Battle of Normandy

- 15. Allied Strategy North of the Seine

- 16. The Battle of Arnhem

- 17. Prelude to the Ardennes

- 18. The Battle of the Ardennes

- 19. The End of the War in Europe

- 20. The German Surrender

- 21. Some Thoughts on High Command in War

- 22. The Control of Post-War Germany:The First Steps

- 23. Difficulties With the Russians Begin

- 24. The Struggle to Rehabilitate Germany

- 25. Last Days in Germany

- 26. Prelude to Whitehall

- 27. Beginnings in Whitehall

- 28. Overseas tour in 1947

- 29. Storm Clouds Over Palestine

- 30. I Make Myself a Nuisance in Whitehall

- 31. Beginnings of Defence Co-Operation in Europe

- 32. The Unity of the West

- 33. Second Thoughts

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery by Viscount Montgomery of Alamein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.