- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A biography of the British Army officer and his role in the Crimean War at the Charge at Balaklava.

Captain Louis Nolan delivered the order that produced one of the most famous blunders in all military history—the Charge of the Light Brigade. Nolan's conduct and the Charge itself have been the subject of intense, sometimes bitter debate ever since. Yet there has been no recent biography of Nolan. He remains an ambiguous, controversial figure to this day. In this fresh and perceptive study, David Buttery attempts to set the record straight. He reassesses the man and looks at his military career, for there was much more to Louis Nolan than his fatal role in the Charge. This sympathetic account of his life throws new light on the Victorian army and its officer class, and on the conduct of the war in the Crimea. It also offers the reader an inside view of the most notorious episode of that war, the Charge at Balaklava on 25 October 1854.

Captain Louis Nolan delivered the order that produced one of the most famous blunders in all military history—the Charge of the Light Brigade. Nolan's conduct and the Charge itself have been the subject of intense, sometimes bitter debate ever since. Yet there has been no recent biography of Nolan. He remains an ambiguous, controversial figure to this day. In this fresh and perceptive study, David Buttery attempts to set the record straight. He reassesses the man and looks at his military career, for there was much more to Louis Nolan than his fatal role in the Charge. This sympathetic account of his life throws new light on the Victorian army and its officer class, and on the conduct of the war in the Crimea. It also offers the reader an inside view of the most notorious episode of that war, the Charge at Balaklava on 25 October 1854.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Messenger of Death by David Buttery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A Family Tradition

Louis Edward Nolan was both the son and grandson of a soldier. By the time of his birth in 1818 the army had already played a large role in the Nolan family’s history and this choice of profession had become an established family tradition. The Nolan family originally hailed from Ireland, claiming to trace their heritage back to the O’Nuallain clan, whose leading members had been influential many years earlier in the service of the Princes of Foharta in County Carlow. It was a respected lineage in Ireland, though it lacked the prestige of former times.1 Babington Nolan, Louis’s grandfather, was a trooper in the 13th Light Dragoons. The 1790s saw him posted to the West Indies during the Revolutionary Wars. The climate made sickness and disease greater foes than anything man could devise; many more men were lost to yellow fever in the tropics than to enemy action. Already a widower, Babington Nolan was himself struck down by yellow fever in 1796 and died in St Domingo, leaving the young John Babington Nolan and his sister orphaned.

John guessed his age at this time to be 11 since like many of his class, he never learned his true date of birth. Fortunately, Colonel Francis Craig of the 13th Regiment had taken a liking to the children and they remained in the care of the army and were even given a bounty, a privilege usually offered only to the orphans of officers. In honour of his father, John began to use his second name in preference, and his benefactor ensured that ‘young Babington’ received a good education. Since the military life had been all he had ever really known, it came as no surprise that by the age of 17 he considered becoming a soldier.

During the early nineteenth century most officers’ commissions could be bought or sold. The purchase system came about through the establishment’s fear of violent rebellion and revolutionary upheaval. In the second half of the eighteenth century, both France and America experienced bloody revolutions, and Napoleon’s resulting dictatorship proved that the fears of the old order were not empty paranoia. Charging large sums for commissions supposedly ensured that only those with a stake in the country could become officers and as such would make unlikely revolutionaries. Wages were also minimal, acting more as a retainer, and the expense of maintaining the kind of lifestyle demanded by most regiments ensured that only men of independent means could afford to be officers. The system was open to abuse and money often changed hands privately, especially when the more prestigious regiments were involved, and captaincies, majorities and colonelships often fetched prices far above the official government rate. In the hope of preventing promotion by purchase alone, officers were obliged to spend a certain period in each rank before being allowed to buy the next step up, but unscrupulous individuals could get around this by going on half pay. Half pay permitted an officer to sell his commission yet still remain on the army’s books and receive half his salary. After waiting for the required period of time without actually performing any service, he could purchase the next rank and return to his regiment.2 Some men remained on half pay for years, returning to the army only to find that they had forgotten their duties or that their knowledge was outdated.

However, deaths in the service through disease, injury or battle also allowed a man to gain a commission without purchase, though such promotions were not always confirmed by the army. If a man was the senior captain in the regiment, dictated by the time served in that rank, he might also gain a promotion if no one could be found to buy the commission in time. Exceptions were also made during the period when England was under threat of invasion during the Napoleonic Wars and badly in need of troops. If an individual transferred from the militia and brought a large number of volunteers with him, he could be awarded a commission as a reward.3 Another exception was possible when an individual was considered a suitable candidate and had a number of respectable backers to recommend him. This would still have to be endorsed by the commander-in-chief since this form of patronage was intended to ensure that money was not the sole criterion for advancement and so allow talented individuals a method of entry.4

This was the manner in which Babington Nolan became an officer. He applied for a commission in 1803, at a time when England lay under the threat of French invasion by Napoleon, who had massed an army at Boulogne. The army was desperate for men and the 17-year-old had good references from Colonel Craig and other officers. He was gazetted as an ensign, the most junior officer rank, in the 61st Regiment of Foot on 9 July 1803. The regimental colonel was George Hewitt. He had been granted his commission under similar circumstances years before, so this demonstration of the power of patronage was not lost on the young officer. Staying with the 61st for only a short period, he transferred to the 70th Foot, a mostly Scottish regiment nicknamed the ‘Glasgow Greys’ which was about to be sent to the West Indies. Babington arrived at regimental headquarters in Antigua in 1804. It was a distant and dangerous posting with disease and climate both taking a terrible toll on the European troops garrisoning the empire. The high mortality rate soon enabled him to gain a lieutenancy, and his immediate superior, Captain Gerald de Courcy, was often absent on military business, which gave him frequent opportunities in the role of acting captain. Having enjoyed a close relationship with the army all his life, he soon fitted in well with the regiment and developed an increasing affection for the Scots.

French strategy against Britain meant that the regiment moved between garrisons as different areas came under threat and when the British seized the Danish fleet at Copenhagen in 1808, the 70th helped to occupy the two Danish-held islands of St John and St Thomas. At this time, Babington married a woman seven years his senior, whose maiden name is unrecorded but whose Christian name was Frances. The union was tragically cut short in the same year when she died at Walworth, probably from disease.5 The 70th were called upon to take part in the attempt to wrest Guadeloupe from the French in 1810–this was probably the only occasion that Babington was under fire during his military career. The operation was successful and the light company received a commendation for capturing artillery batteries dominating the anchorage of Grande Aȋne. Though Babington was afflicted by sickness in the tropics on several occasions, suffering particularly in 1811, it was the high mortality rate and the disinclination that many had for service in the tropics that enabled him to gain a captaincy without purchase on 30 January 1812.

The British Army had been fighting a desperate war in the Iberian Peninsula at this time, and in 1813 the 70th were recalled to Scotland to spend the next three years garrisoned at Perth. There was a large barracks in the town with a depot and prisoner of war camp nearby. Up to 7,000 prisoners were imprisoned there from France, Holland and the German states. Babington was often called upon to help guard the POWs, who could be difficult to manage, and there were frequent escape attempts and occasional riots. There was also civil strife, because of discontent at the increasing pace of industrialization in Britain, and the regiment was called out on several occasions to suppress riots at Montrose and Dundee that year. With his increasing affinity for Scotland, Nolan was undismayed when left in command of the depot as the first battalion sailed to Canada, the 70th being stationed there to guard against American invasion.

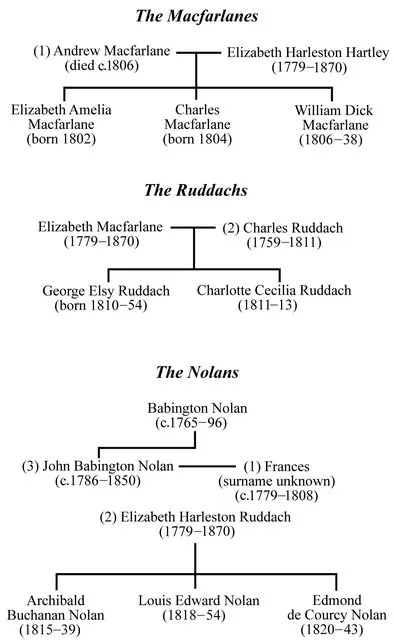

Another reason for his contentment was his meeting with Eliza Ruddach in Perth. He was 27 and she was 34 years old. She lived in Rose Terrace, Perth and as a widow benefited from a pension of £200 per annum for life. Once again, he had fallen for an older woman, and they were married on 12 July 1813 at St John’s Episcopal Church in the East Church Parish of Perth. Nolan wore his full-dress uniform for the occasion and many of the regiment attended the service, presided over by the Reverend H Henry.6 Born Elizabeth Hartley in Holborn, England, in 1779, the bride was the daughter of George Hartley from an old English family. Her first husband had been a Scot named Andrew Macfarlane, whom she had married in 1801. She bore him three children, two of whom died in early childhood. The third, William Macfarlane, was born in 1806 and became Babington’s oldest stepson.

When Macfarlane died suddenly, Eliza was swiftly remarried in 1810 to Charles Ruddach, aged 52. She moved back to Totteridge in England but retained the family home in Bloomsbury. The family owned land in the colonies, which included plantations in Jamaica and Tobago. Eliza had two children, George and Charlotte, the family habit being to name their offspring after family friends: on his birth in 1810, George was named after their local doctor, George Elsy. However, Charles became ill and died shortly after the birth of his daughter in 1811. His daughter followed him swiftly, dying of an illness in January 1813, aged only 2. Though he left their house in Keppel Street and its contents to his wife, his will specified that his youngest son should inherit his shares in the plantations along with his brother Alexander. When Alexander died on a voyage out to see the property, George Ruddach became the sole beneficiary.

Babington’s and Eliza’s courtship had been swift, both seizing upon the opportunity to further their positions in society with matrimony. Babington wanted to rise within the military and a wife would be of great assistance in the society circles he hoped to enter. Furthermore, as a widow she had inherited a considerable amount of money and property from her former husbands and thus enjoyed a regular income. Although she had been married twice, Eliza knew that she needed a husband to help and support her and the children, so the marriage was a practical arrangement as well as a love match, but it suited both partners. Babington Nolan now had a wife and two stepsons.

Over the next few years, he was kept very busy at Perth depot sending recruitment parties all over Great Britain. The Duke of Wellington was fighting his way across Spain at this time and urgently needed new recruits despite his incredible string of victories. Between 1813 and 1815 Babington claimed to have raised over 600 men to send to the colours. The War of 1812 against America was still raging also, and though the 70th had been posted to Lower Canada, where an American offensive was expected, most of the fighting took place along the Niagara frontier and around Lakes Ontario and Erie. It had been an unnecessary conflict that saw almost the entire eastern coast of America blockaded by the Royal Navy, and Washington was taken and sacked by the British Army. Both sides were relieved when a peace treaty was agreed in 1815, the British particularly anxious to resolve the conflict as Napoleon had returned from exile. Fortunately, his imperial ambitions were finally crushed during the Hundred Days’ Campaign, culminating at the Battle of Waterloo that same year.

FAMILY TREES

Hostilities had ceased by the time Babington Nolan was sent to join his regiment in Canada. Archibald Nolan had been born in 1815 and Eliza dutifully accompanied her husband with the entire family. Regimental headquarters were at Kingston in Upper Canada, but the family had to get used to an itinerant lifestyle as Nolan was posted to several garrisons over the next two years including Fort George, Drummonds Island, Amherstburg and York. With a family to support, Babington saw that there were opportunities in the New World and toyed with the idea of settling there permanently. With this in mind he purchased two vacant lots in the town of Markham, north of Toronto, which the family later referred to as ‘Nolanville’. On 4 January 1818, while still stationed in Canada, in York County, Eliza gave birth to Louis Edward Nolan.

During his Canadian service Babington met Thomas Scott, brother of the famous Sir Walter Scott, and their shared interest in Scotland and the army ensured that they became friends. However, the appeal of Canada was waning for the Nolans, and with Eliza pregnant once more, they wished to return to Scotland. It was 1819, and after the disastrous series of wars that had blighted Europe, the government was keen to scale down the army. Though the family was reasonably well off, advancement without purchase in the army was unlikely, so Babington Nolan decided to sell his commission and go on half pay. Captain Thomas Read of the 4th West India Regiment agreed to exchange commissions with Babington, who benefited from the £300 difference between the two regiments. By 1820 the family had returned to Scotland.

With the birth of Edmond de Courcy Nolan, named after Major de Courcy, Babington now had four sons to support; and with his income reduced, the family moved into rooms at 79 Queen Street, Edinburgh, where Louis received his early schooling. Although Babington put himself forward for another placement, hundreds of officers were on half pay in Britain and even the unfashionable regiments had many applicants. Despite their contacts it seemed that prospects for the Nolans were bleak in Scotland, and so in 1829 they decided to move to Italy, where Babington’s military skills might be of use and he had heard there were opportunities in the British Consulate. Louis was 11 years old when the family sailed for Italy. His half-brother William stayed in Scotland and eventually gained a commission in a Highland regiment with his stepfather’s support.

They stayed briefly at Piacenza in the Duchy of Palma but soon moved to Milan. Italy was a divided nation at this time. The Vatican ruled over a separate papal state while the northern principalities had been fought over numerous times during the recent wars, with both France and Austria claiming sovereignty, though by the 1830s many Italians dreamed of independence. In Milan, Babington Nolan was introduced to William Money, the British Consul General. Money was an ex-naval officer who had seen considerable service with the East India Company. With Italy divided into eight states, he was obliged to run several consular centres, especially since Austrian fears of revolutionary activity increased restrictions on foreigners. The Austrian Empire was in decline, increasingly threatened by internal rebellion. To counter this, the Austrians resorted to repressive measures such as censorship of the press, police surveillance and the imprisonment of radicals. The rules were relaxed for British subjects, but they insisted on keeping track of them nonetheless. Any interference in local politics was strongly discouraged and the consulate was expected to monitor the activities of British expatriates and make certain they had the correct licences and visas. The British Consul General was expanding his responsibilities and therefore looked favourably on the application of an army officer.

Babington Nolan was offered an unofficial position in the new consulate in Milan on the understanding that though it might eventually become permanent, this was not guaranteed and he would receive no salary, only being allowed to retain some fees to pay for his expenses. While this was a meagre income, the chance to make influential contacts within the expatriate community and with the Austrians was an incentive. However, the government was annoyed by his unfortunate use of the title ‘His Majesty’s Vice-Consul in Milan’ which he had no right to use, being only a consular agent. He was also foolish enough to use the rank of major before he was officially gazetted (it would be 1838 before he actually received this promotion). Forced to apologize, he rapidly discovered that the government imposed stricter protocols than the military.

For several years Babington Nolan performed his consular duties adequately until, in April 1834, Money returned home complaining of a cold and a stomach disorder, fell into a coma and died shortly afterwards. Perhaps assuming that someone had to take over immediately, as in the army, Babington Nolan acted swiftly, informing London:

I therefore consider it my duty to repair forthwith to Venice and take upon myself the charge. If the Vice Consul at Trieste approves of this measure on my arrival there I shall continue in the performance of the Consular duties there until I am favoured with further instructions from your department.7

Babington had misjudged the situation. The need to replace Money was far from urgent and his own failure to observe official custom was poorly received. Mr Cazaly, his obvious successor in Italy, had more experience than Nolan, which resulted in a serious disagreement. Naturally, Babington’s already tarnished reputation influenced government circles: the authorities insisted that the formalities must be observed. In addition to dealing with a stormy correspondence with Cazaly, they insisted that Babington return some unauthorized fees he had collected, much to his embarrassment. He was confirmed in his position as vice-consul, but taking over Money’s role was out of the question.

Money was eventually replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Thomas Sorrell. Any hopes Nolan may have entertained about forming a good relationship with an ex-army officer were soon dashed: Sorrell took his task very seriously and conducted a far-reaching investigation into consular practices, which revealed unflattering facts about Babington. He considered him a bad businessman and remarked on the fact that he had charged British subjects for unnecessary visas, which had caused complaints. He was over-enthusiastic about making introductions on the consulate’s behalf with more regard to his own interests than the government’s and, despite some useful military intelligence he had gathered, Sorrell recommended his removal from office.8

Such criticism could not have come at a worse time. In 1835 the Austrian Emperor Francis I died, leaving the throne to his son Ferdinand. The new emperor was popular with his subjects but suffered from epilepsy and displayed signs of mental illness. A regency council was established under Archduke Ludwig, which easily manipulated the impressionable monarch. It was dominated by the Archduke and the Ministers Prince Klemens Metternich and Count Kolowrat.9 Metternich had played a leading political role in Napoleon’s downfall and was a leading reactionary, but even his leadership was unlikely to quell the emerging nationalism spreading across Europe and the Austrian Empire. Baron von Hübner believed that many of the Austrian ruling classes were complacent about the widespread unrest and that even Metternich seemed paralyzed when it came to taking effective action:

the more I examine the situation in Italy, the more convinced I am that the game is up. One doesn’t arrest a revolutionary by means of diplomatic notes or leaders in the Press that one reads. ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 - A Family Tradition

- Chapter 2 - Imperial Service

- Chapter 3 - Home and Abroad

- Chapter 4 - The Cavalry Fanatic

- Chapter 5 - The Crimean War

- Chapter 6 - Horse-Dealing with the Bedouin

- Chapter 7 - A Galloper for the QMG

- Chapter 8 - Balaklava

- Chapter 9 - The Fateful Message

- Chapter 10 - Recriminations

- Chapter 11 - Nolan’s Legacy

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index