![]()

Chapter 1

‘I See Dead People’: The Human Body as Archaeology

Whilst in most circumstances the majority of the body is doomed to decompose and effectively disappear relatively soon after death, if the conditions are right the hard tissues of the body (bones and teeth) can survive in a recognizable state for hundreds or thousands of years. Consequently, the skeletal remains of humans and animals are among the most common forms of material evidence encountered by archaeologists. The current chapter is intended to give an overview and general introduction to the ways in which skeletal remains are investigated and the kinds of information that can be gleaned from them. In reality this is a vast subject, with a huge and ever-growing array of published literature. For those wishing to take further interest in the wider subject of biological anthropology a range of suggested texts is given in the Bibliography at the end of this book.

The Nature of Bone

As mentioned in the preceding chapter, bone is not an unchanging, immutable material that stays as it first forms in the body until (and after) death. Rather it is a living tissue supplied by blood vessels and nerves and continually serviced by an army of specialized cells that build additional bone where it is needed and remove or reabsorb it to use the respective minerals elsewhere in the body where it is not. Like other body systems the skeleton is therefore subject to ‘tissue turnover’, a process where just like skin or muscle, bone is continually renewed and remodelled to suit the demands placed on it. This process is the basis of a key principle in human osteology known as ‘Wolff’s Law of Transformation’,1 after Julius Wolff (1836–1902) a German orthopaedic surgeon, attributed with first formally describing it in 1892. This observation states that bone will respond to the biological and mechanical stresses that are placed upon it over time, with the body investing resources in preserving and strengthening parts of the skeleton that are subject to the greatest stress. Consequently it is possible to distinguish the skeleton of a committed bodybuilder from that of a habitual couch potato in terms of differing bone density and in the size and ruggedness of points of muscle attachment where additional bone will have incrementally built up in the former but not the latter.

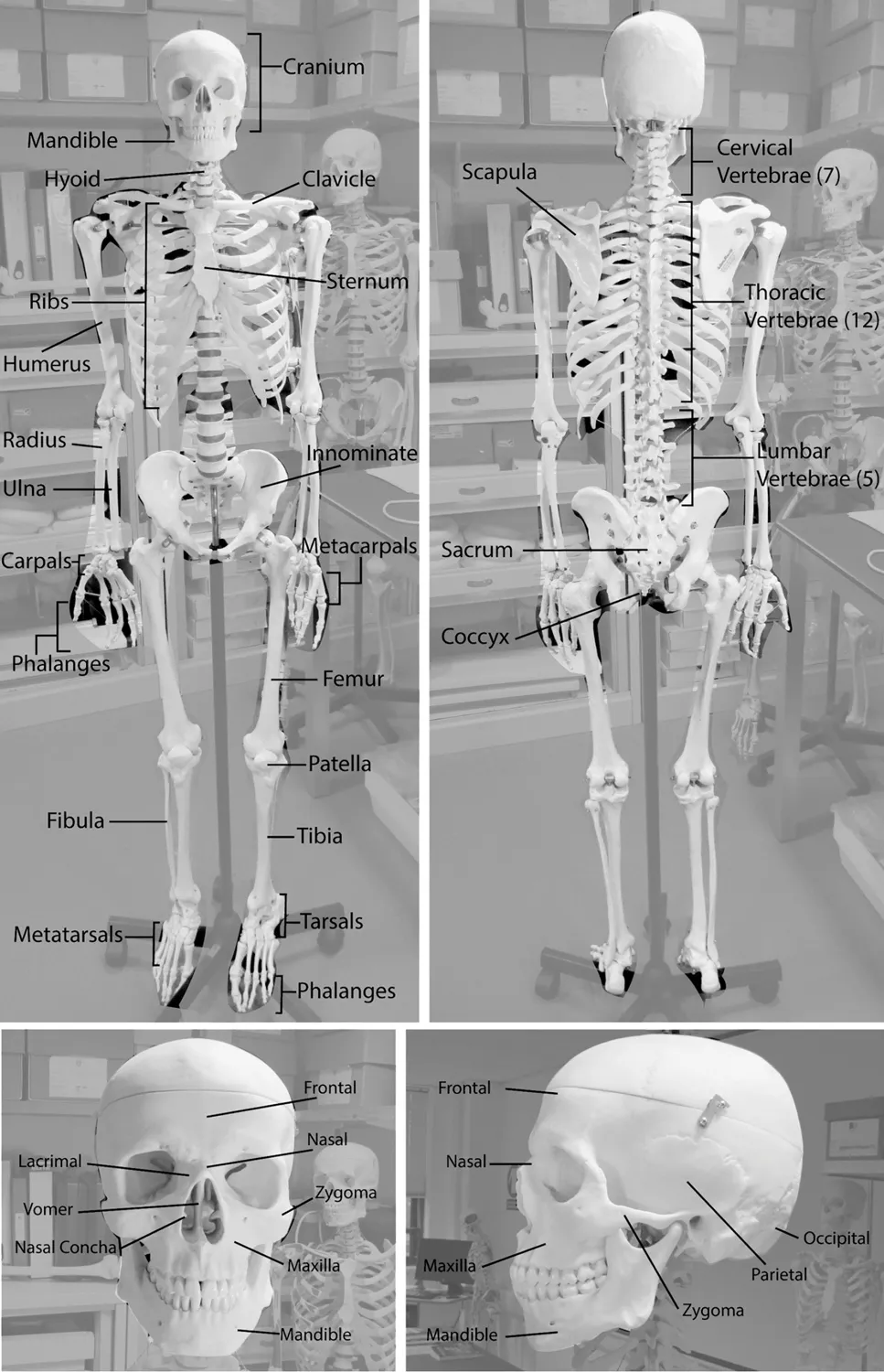

Figure 1.1. The principal bones of the human skeleton.

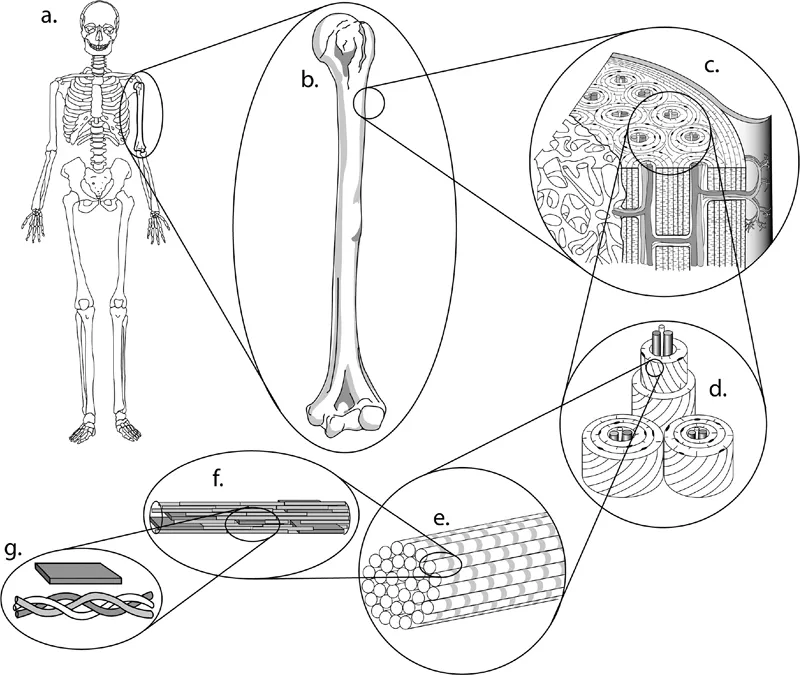

Whilst bone appears to be a solid, off-white, homogeneous material when viewed with the naked eye (Fig. 1.1), at a microscopic level it is in fact a composite material with a fairly complex structure. This is formed of a combination of mineral (mainly calcium) crystals and organic (protein) fibres interwoven in a mutually supporting structure. Twisted fibres of the protein collagen (approx. 5μm or 0.005mm thick) are interlinked in this structure to form a sort of scaffolding into which crystals of a specific form of calcium (called hydoxyapatite) are embedded (Fig. 1.2). These two elements of bone each lend different qualities which combine to give skeletal tissues the important and special properties of being very strong in relation to weight whilst also being resistant to breakage. The calcium crystals confer hardness and rigidity to the bone whilst the collagen fibrils lend it lightness and also resistance to breakage by allowing bone to deform and bend slightly rather than being an entirely brittle material that would simply snap too easily to have been useful to our evolutionary ancestors. It has been noted before that the human skeleton is about as strong as steel but is in fact five times lighter as a consequence of this composite structure.2

Figure 1.2. Human bone shown at various levels from the whole skeletal system (a) and whole bones (b) to the complex microstructure of bone (c−e) down to the level of individual fibres of protein (collagen) that give resilience and a degree of flexibility, interlaced with regular-shaped calcium crystals which give bone its hardness and rigidity (f and g).

Bone Survival

As mentioned in the opening lines of this book human burials are one of the most common forms of evidence encountered in archaeological excavations, but this is not to say that bones are always preserved equally well. Survival of bone over time in the ground is dependent on a range of conditions and is in fact very variable. After death bone is subject to attack from a range of environmental sources, which can include dehydration, cracking and disintegration of surfaces caused by the sun’s radiation and erosion by wind and rain if exposed above ground. Bone also attracts the attentions of various living organisms ranging from scavenging by animals, to mechanical and chemical destruction by plant roots, and digestion at a microscopic level by bacteria. Further to this, bone can be subject to chemical destruction in the form of being gradually eroded and dissolved by ground water percolating through it in addition to dissolution by contact with the surrounding earth in areas where the soil is acidic. This last factor is arguably of greatest consequence in effectively removing all but the faintest traces of bone, sometimes in just a couple of centuries. In ‘acidic’ areas where the soil pH level is hostile to preservation, excavators may find a clearly discernible grave cut containing items buried with the deceased (pottery, metalwork and so on) surviving to be recovered, but nothing remaining of the body except perhaps a smear of discoloured soil. In areas where the geology is more alkaline, bone preservation can often be extremely good over hundreds or thousands of years, but even then the portion of the bone that survives is generally the mineral part with the organic (protein) component decomposing in the ground relatively soon after burial. This latter issue has important implications for the recognition of injuries to the skeleton which are discussed in the following chapter. In rare circumstances other body tissues may also preserve over long periods. Such preservation of soft (as opposed to hard) tissues or ‘natural mummification’ usually involves some sort of extreme environment. This can be extreme cold as in the glacier that preserved the famous Neolithic ‘Ice man’,3 heat and aridity as in the desert-edge burials of Predynastic Egypt or wetness as in the bodies recovered from peat bogs in Northern Europe preserved by this dark and oxygen-starved environment which inhibits the bacteria that would normally cause the body to decay.

Other issues affecting bone survival relate to the conscious actions of the living rather than natural processes. The way in which a society treats its dead can have considerable impact on the extent to which their remains have potential to survive to later be discovered, either accidentally or through deliberate excavation. For example, deeper burials tend to survive better than shallower ones as they are less susceptible to damage by erosion and ploughing, also soil tends to contain less bacteria and invertebrate activity as depth increases. Cremation is obviously unhelpful to the anthropologist but not to the extent popularly believed. Rather than reducing the body to ‘ashes’ as is often thought, burning a body either on a pyre or in a modern crematorium oven produces skeletal remains that are discoloured and fragmented but nonetheless recognizable to an anthropologist and it is often possible to extract a considerable amount of information from them. Furthermore, the process of burning at high temperatures causes the calcium crystals in bone to fuse together, similar to the way clay in a pottery kiln ‘vitrifies’ at higher temperatures. This has the effect of making the surviving bone largely impervious to chemical attacks in acid soils and often the only buried bone that will survive in such regions is where the body has been cremated.4

It is often said that the way we treat our dead in the twenty-first century is rather uninteresting compared to the great variety of practices that existed in the past. There were undoubtedly many past treatments of the dead that are ‘archaeologically invisible’ in leaving no traces that can now be identified. For much of prehistory it is likely that many people were disposed of after death by ‘excarnation’, that is ‘burial’ by exposure either on platforms, in trees or just on the ground surface with scavengers and the elements soon leaving nothing of the body for a future archaeologist to find. Other prehistoric treatments involve long and drawn-out processes where the remains of a number of individuals might eventually be deposited together as ‘disarticulated’ bone – i.e. a jumble of separate bones rather than complete bodies placed in individual graves soon after death. An example of such a context is the long barrow assemblages of Neolithic Britain (mostly dating from the centuries either side of 3600 BC) where elongated earth or stone mounds with timber or stone chambers contain the mixed and disarticulated remains of sometimes dozens of individuals. Such practices present obvious challenges for the anthropologist in that any signs of disease or injury can only be discerned on individual bones and it is often simply not possible to look at the distribution of such evidence throughout the skeleton. So for example such an assemblage might contain a skull with an unhealed depressed fracture, a rib fragment with a partially-healed fracture and a vertebra with an arrowhead embedded in it. In this case it may be impossible to say whether these bones represent a single unfortunate individual who had sustained three injuries or three different people each with one injury. Lastly some societies perfected various means of mummifying their dead, deliberately preserving soft tissues. On the one hand such practices offer excellent opportunities to learn more about the individual than is possible from bones alone, but on the other hand, mummified bodies tend to offer a rather biased sample in that only certain sections of society (generally the upper classes) might be selected for such special treatment.

Who Were They? Profiling the Dead

Once issues of bone survival have been taken into account, the first objective in making sense of any skeletal assemblage is to establish the demography of the sample – i.e. ‘whose’ bones are present? Whether looking at a single individual or a cemetery containing hundreds or even thousands of burials, the same initial questions need to be addressed before any other interpretations can be made. Perhaps obviously, the two most important characteristics to assess are the sex and the age-at-death of the people represented. These two key factors are crucial when trying to make sense of any further areas of inquiry such as health, diet, movement/migration during people’s lifetimes and in the case of this book violence and conflict. Rather than either sex possessing any specific features which the other doesn’t have, male and female skeletons can be told apart by differences in the precise shape and to an extent the size of particular structures throughout the body. The bones that make up the pelvis5 unsurprisingly differ to the largest extent with the broad bowlshaped female pelvis differing from the taller, more compact male version. Similarly, various features seen on the skull are generally more strongly and ruggedly expressed in men than women. However, neither region of the skeleton is infallible and many people exhibit a mix of features with more or less masculine and feminine expression throughout their skeletons. As a consequence, determining sex in this way (visual assessment) can never be 100 per cent accurate, although blind tests have shown that it often comes fairly close. Where skeletons are complete and well-preserved sex determinations are usually correct around 95 per cent of the time.6 However, as remains become less well preserved, levels of accuracy drop accordingly. The pelvis alone gives a reported accuracy of 90 per cent, followed by the skull (approximately 85 per cent) and mandible 70 per cent. Where assessments are made from the size of particular features such as measurements of the long bones of the limbs, accuracy rates fall to between 70 per cent and 80 per cent.

Various parts of the skeleton can offer indications as to how old an individual was when they died. For the most part such estimations rest on the principle that the skeleton goes through a prolonged sequence of development lasting from before birth until early adulthood. Rather than simply being ‘mini-adults’ the skeletons of children differ from those of mature people in several ways. In particular the juvenile skeleton has different numbers of elements as parts of different bones appear at different times during a person’s early years, for example the ends of the long bones of the limbs do not fuse to the main shaft of the bone until the respective bone stops growing. This process (known as epiphyseal fusion) occurs in a predictable sequence which allows for judgements regarding the age of individuals up to their mid-20s which are fairly accurate (i.e. within two–three years either side). The development of the teeth follows a similar sequence and is an even more precise indicator up to the age of around 21 by which time the third molars (wisdom teeth) are normally in place with no further new teeth to follow. However, once an individual reaches their mid-30s a different principle comes into play as the skeleton begins a gradual process of degeneration which continues until death. In general this presents more of a challenge to the osteologist, as just like other parts of the body, different people’s skeletons deteriorate at different rates. We have all known people who look older than their years and can all name celebrities who look younger than they really should. Such variation is determined largely by our genes although diet and lifestyle certainly also have a strong part to play. Consequently, age estimations for adult individuals tend to become wider and less accurate with increasing age. As with sex determination these issues are also made more difficult when the skeleton is incomplete or badly preserved and consequently it is common for ages simply to be estimated within broad ranges i.e. ‘Young adult’ (20–35 years), ‘Middle adult’ (35–50 years) and ‘Old adult’ (50 years and older).7 The open-ended nature of this last category illustrates a further problem in that establishing upper limits for the age of people in later life is really quite difficult and is a problem anthropologists have yet to resolve. So, whilst it may be clear that a person was over 50 it may be difficult to distinguish the bones of a 60-year-old from those of an 85-year-old.

Once these initial observations determining sex and age have been established the osteologist may wish to investigate any number of other variables to help characterize the individual or group being studied. Such variables commonly include standing height (stature), ancestry,8 the effects of strenuous activity and dietary habits. There are in fact so many ways to study the human skeleton that it is rare to find all or even most of them applied in any single study. Instead the aspects of skeletal remains studied are largely determined by the questions a particular researcher is trying to answer.

‘I Told You I Was Ill’: Disease in the Skeleton

At the level of reconstructing individuals the questions anthropologists tend to ask regarding human skeletons fall into two broad areas, ‘who was this person?’ and ‘what happened to them during their lifetime?’ Whilst the former is addressed by the biological profiling described above, the latter can be detected in relation to various events and processes including signs of disease. A large proportion of the illnesses that affect human beings leave no signs on bone. Many pathological conditions simply do not affect bone whilst others take effect too quickly to cause discernible changes in the skeleton. For example, in the case of acute infections (those with rapid onset) the sufferer tends to either recover or die before any noticeable bony response can occur. Such a lack of skeletal changes is therefore unrelated to the seriousness of the condition. Whilst the common cold is not detectable in bone, largely because people get better within a few days or weeks, more serious infections such as typhus or bubonic plague tend to kill the patient within a similarly short time. By definition then diseases that do leave signs on the skeleton are ‘chronic’ conditions, those that take effect slowly and persist for an extended period. In fact this category encompasses a very wide range of ailments including conditions as diverse as joint diseases such as arthritis, dietary deficiencies such as scurvy and infectious diseases like tuberculosis or venereal syphilis.9

Accurately recognizing medical conditions is not always an easy endeavour for doctors treating living patients with the benefit of modern diagnostic techniques and the added bonus that the patient can say how she or he feels. Most of us have at some time had friends or relatives who have suffered with an ailment for a considerable time before its cause was finally identified. It is not surprising therefore that attempting to diagnose medical conditions in the dry bones of ‘patients’ who are no longer able to talk to us is considerably harder. This issue is compounded by the fact that changes to bone caused by disease processes often look very similar to each other. Bone can in fact only respond to disease in two ways, either by building more bone or by losing bone in a given area. This means that individual lesions (abnormalities) caused by different disease conditions can often look very similar to each other. Where specific pathological conditions can be identified it is commonly the patterning of such lesions across the skeleton that is distinctive rather than the appearance of any single change to bone. Once again the issue of how much of the skeleton is preserved is therefore very important. For example, leprosy can produce very distinctive changes in the bones of the extremities and the central part of the face. However, in a case where the small bones of the hands and feet and the delicate facial bones do not survive it would be impossible to recognize the condition no matter how well preserved the rest of the skeleton was. Such issues of bone survival are similarly important in recognizing injuries.

Things don’t Equal People: From Hobbes to Rousseau

Whilst the earliest archaeological work in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries commonly investigated human burials, the deceased individuals themselves (or at least their bones) were generally afforded little attention, with the interests of excavators focused instead on the things people had been buried with (pots, metalwork and so on). In this respect such excavations constituted little more than treasure hunts or mining expeditions seeking interesting or valuable objects. Human remains were rarely commented upon directly and were seldom retained other than as objects of general curiosity (and even then it was usually just the skulls that were kept). By the m...