eBook - ePub

Northern Ireland: The Troubles

From The Provos to The Det, 1968–1998

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

It is, of course, no secret that undercover Special Forces and intelligence agencies operated in Northern Ireland and the Republic throughout the troubles, from 1969 to 2001 and beyond. What is less well known is how these units were recruited, how they operated, what their mandate was and what they actually did. This is the first account to reveal much of this hitherto unpublished information, providing a truly unique record of surveillance, reconnaissance, intelligence gathering, collusion and undercover combat.An astonishing number of agencies were active to combat the IRA murder squads (the Provos), among others the Military Reaction Force (MRF) and the Special Reconnaissance Unit, also known as the 14 Field Security and Intelligence Company (The Det), as well as MI5, Special Branch, the RUC, the UDR and the Force Research Unit (FRU), later the Joint Support Group (JSG)). It deals with still contentious and challenging issues as shoot-to-kill, murder squads, the Disappeared, and collusion with loyalists. It examines the findings of the Stevens, Cassel and De Silva reports and looks at operations Loughgall, Andersonstown, Gibraltar and others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Northern Ireland: The Troubles by Kenneth Lesley-Dixon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1: NATIONALIST PARAMILITARY ORGANIZATIONS

Nationalist paramilitary organizations years active / operational

| Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA) | 1994 to present |

| Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) | 1974–2009 |

| Irish People’s Liberation Organization (IPLO) | 1986–1992 |

| Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) | 1970–1972 |

| Óglaigh na hÉireann (ONH) (Real IRA splinter group) | 2009 to present |

| Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) | 1970–2005 |

| Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA) | 1997 to present |

| Saor Éire (SÉ) | 1967–1975 |

Provisional Irish Republican Army

“We declare our allegiance to the 32 county Irish republic, proclaimed at Easter 1916, established by the first Dáil Éireann in 1919, overthrown by forces of arms in 1922 and suppressed to this day by the existing British-imposed six-county and twenty-six-county partition states.”

IRA mission statement, December 28, 1969

In many ways the Provisional IRA (Óglaigh na hÉireann) defined The Troubles; they were never far away from many of the nationalist murders, bombings and shootings in Northern Ireland and on the mainlands of the UK and Europe. The carnage and misery the IRA wreaked—human and economic—is incalculable. Given their mandate, to force the United Kingdom to negotiate a withdrawal from Northern Ireland and to destroy anyone that got in their way, this is hardly surprising. So, they shot and bombed their way through The Troubles, ever true to their cause, constantly energized by frantic paper-selling and viewer-fixated British media coverage—the ‘oxygen of publicity’—while at the same time enraged by that same media’s plainly imbalanced coverage that assigned to them the lion’s share of the atrocities when the loyalists were equally culpable in many respects.

The funeral of Seán South, 5 January 1957. South (1928–57) was a member of an IRA unit led by Sean Garland on a raid against a Royal Ulster Constabulary barracks in Brookeborough, County Fermanagh on New Year’s Day, 1957. He died of wounds sustained during the raid along with another IRA volunteer, Fergal O’Hanlon.

Cathal Goulding (1923–1998) was Official IRA chief of staff from 1962 to 1972. He was responsible for repositioning the IRA further to the left in the 1960s, opposed the policy of abstentionism and inculcated a Marxist interpretation of Irish politics. The focus was on class struggle and its aim was to unite the Irish nationalist and unionist working classes in order to overthrow capitalism, both British and Irish. The Official IRA, like the Provisional IRA, conducted an armed campaign but Goulding argued that this ultimately divided the Irish working class. After public outrage and horror at the shooting of William Best and the bombing of the Aldershot barracks, the Official IRA announced a ceasefire in 1972.

Ranger William Best died in the wake of Bloody Sunday in 1972 in which the British Army shot dead fourteen unarmed civilians. Best (19) was a local Derry man home on leave from the British Army in Germany, staying at his parents’ house in the Creggan. He was abducted, interrogated and summarily shot by the Official IRA. The following day, 500 women marched on the Republican Club offices in protest. Nine days later, on May 29, the Official IRA declared their ceasefire. The Provisional IRA initially declined to follow suit, but after informal approaches to the British government they announced a ceasefire from June 26.

When British troops disembarked in Belfast in 1969 they were welcomed by Protestants and Catholics alike: the army signified protection against sectarian attacks; the nationalists had no trust in the RUC. Soldiers were plied with tea and toast in the Catholic Falls Road area of west Belfast; these encouraging images were shown all around the world and gave signs of hope.

This photo was taken by the Irish photographer Colman Doyle. The original caption: “A woman IRA volunteer on active service in West Belfast with an AR-18 assault rifle.”

Seemingly the British government was at pains to do “nothing that would suggest partiality to one section of the community”; relations between the army and the local population were at a high following army assistance with flood relief in August 1970. However, the Falls curfew and a situation that was insensitively described at the time as “an inflamed sectarian one, which is being deliberately exploited by the IRA and other extremists” ensured that the hospitality did not last for very long. Protestants soon saw the army as their exclusive protectors against the Provisional IRA while to many Catholics the army was an oppressive force supporting unionist rule. One senior NCO tells, in John Lindsay’s Brits Speak Out: British Soldiers’ Impressions of the Northern Ireland Conflict how “On the other [republican] side, some of the people whose homes we’d have to search would be as nice as pie. Once the curtains were drawn they would chat to you and make you cups of tea.”

Nothing exceptional about that you might say, but in Ireland, north and south, a cup of tea is a potent symbol of friendship and hospitality. Less attractively, Royal Military Police investigations into over 150 killings by the army in the early 1970s were known as “tea and sandwich inquiries” to denote the casual, shabby nature of the inquiries and the cozy relationship that existed between the RUC and the army.

The Troubles were never the ‘people’s war’ they are often described as: the Protestant majority (65% at the time) was fervently against nationalist terrorism; many in the Catholic minority, while ideologically supportive, were against violent means.

A key policy of the Provisional IRA and of Sinn Féin was to foster urban insurgency, civil disorder which would seriously exercise and strain routine policing and thus create a threat to national security and advance their desire for a one-Ireland island. Sinn Féin worked quietly in the background to manipulate civil rights groups towards a more nationalist agenda while their brothers in the Provisionals provoked sectarian tension with gusto. Catholics fighting Protestants in the streets of the North was good PR for the Provos and a highly effective recruiting sergeant. Police confrontation with civil rights protesters was then sold by Sinn Féin as attacks on nationalists by a police force that was anti-Catholic, thus destroying any pre-existing cross-community element in the civil rights movement and driving a wedge between Catholics and Protestants.

The Civil Rights movement

The non-violent civil rights campaign has its roots in the mid-1960s, a collection of groups like the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Campaign for Social Justice (CSJ), the Derry Citizens’ Action Committee (DCAC) and People’s Democracy. Their collective objectives were an end to job discrimination—there was evidence that Catholics/nationalists were less likely to get certain jobs, especially jobs in local government; an end to discrimination in housing allocation—there was evidence that unionist-controlled local councils allocated housing to Protestants before Catholics/nationalists; introduction of universal one man, one vote—in Northern Ireland, only householders could vote in local elections, while in the rest of the United Kingdom all adults had the franchise. The discrimination in housing provision disenfranchised more Catholics than Protestants; an end to gerrymandering of electoral boundaries which meant that nationalists had less voting power than unionists, even where nationalists were a majority; reform of the Royal Ulster Constabulary which was over 90% Protestant and notorious for sectarianism and police brutality; repeal of the Special Powers Act—this allowed police to search without a warrant, arrest and imprison people without charge or trial, ban any assemblies or parades, and ban any publications; the Act was being used almost exclusively against nationalists.

Another aspect typical of the disrupting insurgency was the IRA’s policy of bombing local businesses to deter inward investment and job creation in the province. Inevitably, the stones and petrol bombs were exchanged for bombs and bullets, and for premeditated sectarian murder and torture. The killing squads had arrived.

In its pursuit of Irish republicanism down the years, the IRA has taken on many forms. It first emerged in the Fenian raids on British towns and forts in the late 1700s and 1860s. Between 1917 and 1922 the Irish Republican Army (the ‘Old’ IRA) was recognized as the legitimate army of the Irish Republic; in April 1921 the first split followed the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, with supporters of the treaty forming the nucleus of the National Army of the newly created Irish Free State (also known as the government forces or the regulars and later known as the Irish Defence Forces), while the anti-treaty forces continued to use the name Irish Republican Army, (the Republicans, Irregulars or Executive forces).

The anti-treaty wing of the Irish Republican Army (1922–69) fought and lost the civil war (1922–23) and consequently refused to recognize either the Irish Free State or Northern Ireland, preferring to see them as creations of British imperialism. It existed in one form or another for over forty years before the split in 1969.

In the 1930s, the remainder of the IRA, including that part of the Old IRA organized within Northern Ireland, started a bombing campaign in Britain, a campaign in Northern Ireland and some military activities in the Free State (later the Republic of Ireland). The relationship between Sinn Féin and the IRA was re-established in the late 1930s

The original Official IRA (OIRA), what was left of the IRA after the 1969 schism, was largely marxist and became inactive militarily while its political wing, Official Sinn Féin, became the Workers’ Party of Ireland. The Provisional IRA (PIRA) seceded from the OIRA in 1969 over abstentionism and how to deal with the increasingly violent Troubles. Despite being unsympathetic to OIRA’s marxism, it developed a left-wing orientation and increasing political activity. The Continuity IRA (CIRA), broke from PIRA in 1986 because the latter ended its policy on abstentionism, thus recognizing the authority of the Republic of Ireland. The Real IRA (RIRA) was a 1997 breakaway from PIRA consisting of members opposed to the Northern Ireland peace process.

In April 2011, former members of the Provisional IRA announced a resumption of hostilities, and that they “had now taken on the mantle of the mainstream IRA”. They also claimed, “We continue to do so under the name of the Irish Republican Army. We are the IRA” and insisted that they “were entirely separate from the Real IRA, Óglaigh na hÉireann [ONH] and the Continuity IRA”. They claimed responsibility for the April killing of PSNI constable Ronan Kerr as well as responsibility for other attacks that had previously been claimed by the Real IRA and ONH. There has been sporadic violence since the Good Friday Agreement of April 1998, including a campaign by anti-ceasefire republicans.

The Troubles turned out to be the longest significant campaign in the history of the British Army. The British government has always maintained that its forces were neutral in the conflict, fighting to uphold law and order in Northern Ireland and the right of the people of Northern Ireland to democratic self-determination. Nationalists saw it differently, viewing the state forces as forces of occupation or partisan combatants. Key findings by the Police Ombudsman’s Operation Ballast investigation—a three-and-a-half-year investigation into a series of complaints about police conduct in relation to the murder of Raymond McCord Junior in November 1997—confirmed that the RUC and Special Branch colluded more than once with loyalist paramilitaries, were involved in murder and obstructed the course of justice when claims of collusion and murder were investigated

So, we have a conflict which, right from the start, makes routine use of murder squads which are characterized at times by a shoot-to-kill mandate championed by various paramilitary organizations, the police and the British Army.

The violence exploded between the years 1970 to 1972, peaking in 1972 when nearly 500 people, just over half of them civilians, died in those three years. By the end of 1971 there were twenty-nine barricades in place in Derry, blocking access to Free Derry. The IRA planted nearly 1,800 bombs—an average of five a day—in 1972. In 1972 there were more than 10,600 shootings in Northern Ireland.

Unionists, of course, blamed the violence squarely on the Provisional IRA and the now separate Official IRA. The older IRA had espoused non-violent civil unrest but the Provisional IRA was intent on waging ‘armed struggle’ against British rule to gain their ends. The new Provisional IRA took on the role of ‘defenders of the Catholic community’, splitting the community rather than doing anything to bring it together. The 1971 introduction of internment without trial didn’t help; of the first 350 detainees, none was Protestant. To add insult to injury, sloppy intelligence and operational bungling ensured that precious few of those interned were actually republican activists at the time of their arrest.

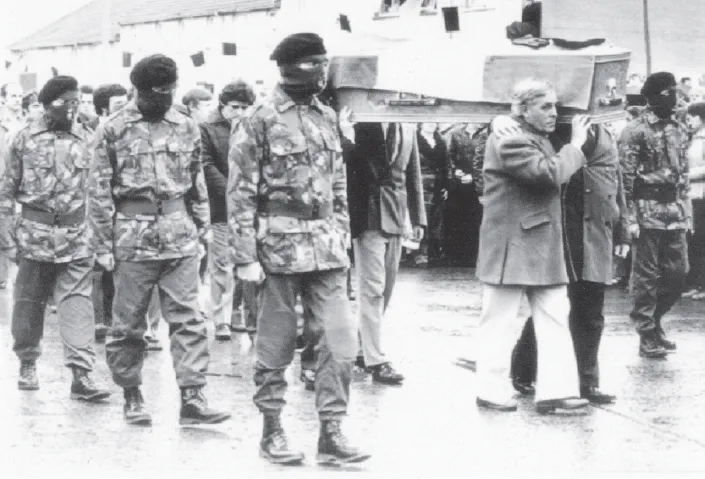

One of many IRA funerals in the 1970s.

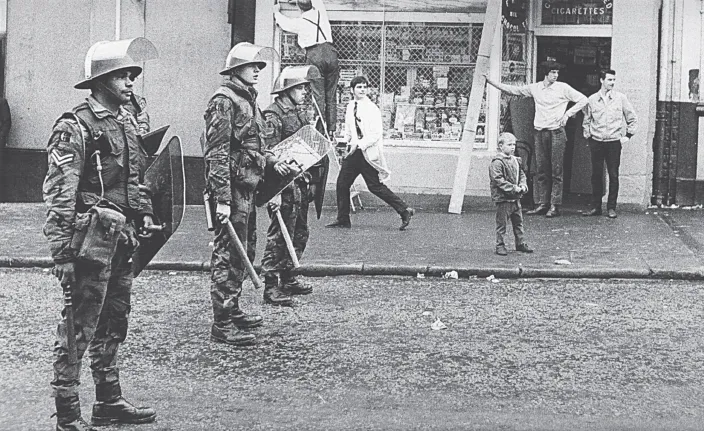

British troops on the Shankill Road in 1970.

The RUC was the first security force to suffer at the hands of the Provisional IRA when in August 1970 two constables were murdered in a bomb attack in S...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Glossary of Terms

- Preamble

- Part 1: Nationalist Paramilitary Organizations

- Part 2: Loyalist Paramilitary Organizations

- Part 3: British Security Forces

- Further Reading