- 181 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

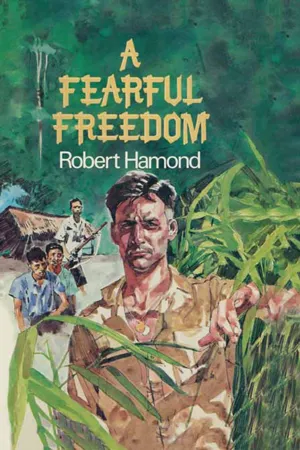

A Fearful Freedom

About this book

A British Army soldier shares his harrowing journey to reunite with his regiment after getting wounded and separated in the Malayan jungles during WWII.

In A Fearful Freedom, author Robert Hammond tells the story of Private E. J. Wright of the 6th Norfolks and his survival behind the lines of Japanese occupied territory during World War II, including his work on the Burma Railway.

In A Fearful Freedom, author Robert Hammond tells the story of Private E. J. Wright of the 6th Norfolks and his survival behind the lines of Japanese occupied territory during World War II, including his work on the Burma Railway.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Fearful Freedom by Robert Hammond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

| Glossary | ||

| Author’s Note | ||

| Prologue | ||

| Chapter | One | Abruptly Into Battle |

| Two | The Water Tower and After | |

| Three | The Ordeal Begins | |

| Four | Journey out of Nightmare | |

| Five | Back Among Friends | |

| Six | Death Shack | |

| Seven | The Guerrilla Camp | |

| Eight | The Enemy Closes In | |

| Nine | Major Barry’s Disastrous Expedition | |

| Ten | Out of the Valley of the Shadow | |

| Eleven | John Cross’s Story | |

| Twelve | Back in Touch | |

| Thirteen | Journey Towards Freedom | |

| Fourteen | The Rendezvous | |

| Epilogue | ||

| Maps | ||

| Appendix | ||

| Bibliography | ||

| Acknowledgements | ||

GLOSSARY OF LOCAL TERMS USED

| Atap Hut | Wood/bamboo-framed hut thatched and clad with overlapping fronds of palm leaves, dried and worked in a certain way. (Malay. Rumah Atap or Pondok Atap). |

| Bĕlachan | Fermented fish/prawn paste with an appalling stink and a very strong taste. |

| Bĕlukar | (Pronounced ‘Blooka’). Secondary woods growth which springs up where jungle has been cleared. Dense and stifling under a close canopy, it makes going very difficult although it is not quite impenetrable. |

| Beri Beri | Vitamin ‘B’ deficiency disease. Wet form is oedema or elephantiasis. Dry form is a numbness spreading from fingers and toes towards body. |

| Bertam | A stemless palm 15–20 feet tall and very close growing. The leaf has a spiny stem with spiny leaflets growing off it. |

| Bukit | Hill. |

| Changkul | Shaped like an adze, used in Asia for tilling or hoeing ground. Takes the place of the European spade/pick/hoe/fork. |

| Elephant Grass | A bamboo-like grass, 6–8 feet tall. |

| Gunong | Mountain. |

| Ingping | English soldier. (Chinese). |

| Kampong | Village. |

| Kempeitai | Japanese security police similar to the German Gestapo. |

| Kerengga | Red ants which make leaf nests in secondary growth and undergrowth. Their bite is painful. |

| Kongsi House | Communal house. (Chinese). |

| Kuala | The mouth or estuary of a river, or the junction of a tributary stream and a river. |

| Kueh | Generic name for cakes which can be made out of flour including tapioca root flour. |

| Lalang | Spear grass (imperata cylindrica). Sharp-pointed erect grass about 3 feet tall which colonises abandoned cultivated land. |

| Mengkuang | (Pandanus). A stemless palm which forms dense thickets in swamp or areas liable to flooding. Leaves are stiff and pointed, up to 20 feet long and about 4 inches wide. A row of downward-curving thorns grow on both edges of each leaf and a row of upward-curving thorns run along the centre spine of each leaf. Almost impenetrable. |

| Nibong Tree | Nibong palm. The growing point (heart) of all palms makes good eating. |

| Parang | A jungle-slashing knife like a machete. |

| Rattan | Over twenty varieties of climbing palm which can be split and used instead of rope or string, especially in the construction of huts. |

| Sakai | A blanket term for various aboriginal tribes who live in deep jungle. |

| Sampan | Small boat (Chinese). |

| Sungei | River or stream. |

| Tanjong (Tg) | Headland. |

| Ubi Kayu | Root of tapioca. Poor eating except when young, and of low nutritional value as the flour is almost pure starch. Some varieties are poisonous unless reduced to flour. |

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Between 8 December, 1941, when the Japanese invaded Malaya, and 15 February, 1942, when they captured Singapore, they inflicted a series of running defeats on the British, Indian and Australian troops opposing them. Inevitably during the confusion of this long retreat in and out of dense jungle, men became detached from their units. Alone or in small groups they struggled to rejoin their comrades and, when they failed to find them, simply to survive.

Most failed even in this. They were either rounded up by enemy patrols or betrayed to them by the local inhabitants; or, if they avoided this fate, sooner or later died of starvation and disease. A handful, however, tougher or luckier, came through; one of these was Private E. J. Wright of the 6th Norfolks, and this is his story.

Why it has not been told before is explained in the epilogue: how I came to write it is another story. It so happened that I too was in the Royal Norfolk Regiment, though in a different battalion from Jim Wright. I shared with him the chaos and despondency of that heart-breaking retreat south through Johore towards the illusory refuge of Singapore.

Thirty years after these events, I was at a reunion of FEPOWs and there met an ex-member of 6th Norfolks, Bert Hall. In the course of conversation he mentioned how, soon after the war, he had come face to face with Jim Wright, an old friend of his who he thought had died during the retreat. Jim, by nature a reticent man, had told Bert something of the three-and-a-half years he had spent behind the Japanese lines, and then, as if the subject was still too painful, had abruptly shut up. As far as Bert knew, Jim had never told anyone else of his experiences, preferring to try and forget them.

I was intrigued and took Jim’s address. Through our regimental records, I discovered that, indeed, No 5776863 Pte Wright E. J. had been posted missing, believed killed, at Rengit, Malaya, on 27 January, 1942; but his name did not appear on the official Roll of Honour issued by the War Office. This substantiated Bert Hall’s account, and soon afterwards I went to see Jim Wright.

I found a sturdy, reserved, but friendly man in his late fifties who, after some hesitation, gave me the outlines of his remarkable story: one, I felt, that even at this late date deserved telling. Would he help me to get it down on paper? Because I had also fought in Johore and in the same regiment at the same time, and he felt that I would know what he was talking about, he agreed.

Jim, it turned out, had a phenomenal memory for dates and details; and it was from the notes he provided that I have been able to write this extraordinary story of suffering and survival. In truth, as it unfolded, I found myself becoming totally involved with these young soldiers, sharing their disappointments and despair, their grief at the death of comrades, their rare moments of relief and joy. Most of all, I came to feel unbounded admiration for their courage and resourcefulness, thrown, unprepared as they were, into that strange and dangerous world.

Robert Hamond

PROLOGUE

As the light faded a hush fell over the jungle. Even the cicadas in the undergrowth ceased their frenzied whirring, stopping suddenly as if they had been turned off by a switch.

In the oppressive silence Jim Wright became acutely aware of his utter loneliness. For a moment panic seized him and he wanted to shout and scream, to shatter the quiet all around him and perhaps, by some miracle, to recall his comrades to his help.

But he knew in his heart that they would never come back. It was over an hour now since they had silently abandoned him to his fate, desperately seeking a slender chance of survival for themselves without the crippling handicap of a wounded man who could not walk without help.

During that long hour the stark hopelessness of his predicament had become apparent to Jim, and he realized that his luck of the past week had now run out. Hardly able to move, far less walk, with no weapon, food or water, and completely lost in this seemingly endless jungle, he saw that he had virtually no hope of survival. He was only twenty-three years old. Since he had landed in Singapore, barely three weeks earlier, he had had to endure a succession of nightmare events and narrow escapes from death, and had seen many of his comrades die around him.

In the last glimmer of light he crawled painfully to the foot of a large tree and leaned his back against it. His head ached intolerably and his wounded foot throbbed without pause. He saw that it had bled copiously as a result of his exertions during the day, and his boot was full of blood.

A sense of despair and misery filled his mind. Why bother to struggle, he thought; he would die here anyway so why try to postpone the inevitable? No one would ever find him in this dense undergrowth, not even the natives or the Japanese patrols. Perhaps it would have been better if he had been killed with the others in the ambush; they were beyond all pain now, whereas he would have to endure a lingering and lonely end. He recoiled from the thought of death. Closing his eyes, he tried to shut out his surroundings and force his tired brain to rest.

After a while he shifted his position a little to try and ease the pain which ran up his right leg from the throbbing wound. It was pitch dark now and the jungle had come alive again, full of strange noises and rustlings which seemed menacing and set his nerves on edge. He licked his parched lips with a desperate longing for a drink, but his water bottle was empty.

He moved his position again and the agony of his foot drew an involuntary cry from his dry throat. Mosquitoes were now swarming on him, droning in his ears and biting his hands and face, but he was too exhausted and miserable to care. If there are mosquitoes, he thought dully, there must be water somewhere at hand, but he knew that he could not search for it until daylight and he was now so listless that he felt no enthusiasm for any effort even then.

He turned his thoughts back to his home, because he found this comforting. He pictured his school holidays, spent with his father in the woods of the Heydon Estate. His father and grandfather had spent all their working lives there, as gamekeepers. Jim had learned much from his father, who had taught him to observe the woodland wild life and to find his way about the woods without getting lost. Jim had learned to shoot straight and to set traps for vermin, and he came to love the woods, never minding being alone with the wild creatures.

He wondered what his father would have thought of these Malayan jungles, thick, stifling and sinister, so different from the clean, sweet-smelling woods of Norfolk. He tried hard to picture the advice which his father would have given him in his present situation, but without success.

As those long dark hours dragged slowly by, his utter exhaustion and tormenting thirst made him light-headed and feverish. His mind wandered back and forth until at times he thought that he was at home, and at others that his comrades were still with him. And then the cruel realization that he was alone and in the jungle would return again to his consciousness. Desperately he shut it out and tried to concentrate on thinking of his home and parents. At last, in spite of his pain and discomfort, he sank into a merciful oblivion which gave him some rest.

CHAPTER ONE

Abruptly into Battle

The 6th Battalion, The Royal Norfolk Regiment, in which Jim Wright was serving, was a unit of the ill-fated 18th Division which had sailed from the Clyde late in October, 1941, bound for Egypt. After a long sea voyage via Canada and Cape Town the Division had been diverted to India. Two days out of Bombay the 53rd Infantry Brigade was detached and sent to Singapore.*

By the time the brigade disembarked on 13 January, 1942, Japanese forces had almost reached the State of Johore.

Prior to mid-1941 the defence of Singapore, Britain’s main stronghold in the Far East, had been based on the assumption that any enemy attack would come from the sea. To the north China was an ally already at war with the Japanese, the French still held Indochina and Siam was a friendly neutral country. An attack down the Malayan peninsula was, therefore, considered extremely unlikely and, in any case, the jungles of Malaya were deemed to present an impenetrable barrier.

The defence of Singapore was accordingly planned round a strong Navy, based on Singapore, but also co-operating with Dutch naval forces in the Dutch East Indies, shore-based naval guns in emplacements, and a string of airfields throughout the length of Malaya, bombers from which would make a sea-borne attack on Singapore too costly to contemplate.

The Army maintained a small garrison which carried out the ceremonial and internal security duties necessary in peacetime, and sent detachments to Malaya and Borneo.

When the Japanese invaded Indo-China in July, 1941, Singapore’s defence plans were rendered obsolete overnight. The enemy now had a modern naval base and airfields 300 miles from north Malaya and 600 miles from Singapore itself. They then ‘allied’ themselves by force to Siam and thus effectively controlled road and rail routes running south to Malaya.

This alarming situation necessitated some reinforcement of Singapore and Malaya, though Whitehall and the Government in Singapore were reluctant to admit that a real threat existed. Modern aircraft, tanks and additional naval forces were requested, but Singapore had a low priority compared with other theatres of war. Those armaments which did eventually arrive came far too late to influence the outcome of the battle.

Static defences were not built, because money for their construction was not approved by the Treasury. When funds were eventually released the civilian work force was unwilling to work on defences because of enemy bombing. Also General Percival considered that the building of defences on Singapore Island would lower morale because it presumed the loss of Malaya to the enemy.

Shortly before the Japanese invasion, our army – British, Australian, Indian and locally-raised troops – was deployed in Malaya to meet this threat. Virtually none had trained in jungle warfare and some Indian regiments had not completed even their basic training before being rushed from India. Aircraft were few and obsolete, there were no tanks and field artillery was in such short supply that some regiments had to be equipped with 3-inch mortars instead. Naval forces were outnumbered and out-gunned, especially after the loss of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse.

Conversely, the Japanese forces had campaigned for years in China and, prior to the invasion of Malaya, had carried out intensive jungle warfare training in Indo-China. They had tanks, modern aircraft and overwhelming naval support. Even so, Whitehall and the military command continued to underestimate the Japanese capability throughout the battle.

Although disfigured by ruthlessness and an almost manic brutality – the massacre of prisoners and wounded was typical – General Yamashita’s campaign was brilliantly planned and executed. Using the jungle to bypass our defensive positions, sometimes landing units by sea behind our lines, he ensured that no defensive position could be held for long and made every tactical withdrawal a costly and perilous operation.

Failure to hold the Japanese att...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents