- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This oral history shares firsthand accounts of Britain's child evacuees who were sent to live away from home at the outbreak of WWII.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain initiated Operation Pied Piper, evacuating more than three million civilians out of areas considered prime targets for bombing. It was the largest ever transportation of people across Britain, and most of those moved to safety in the countryside were schoolchildren.

Social historian Gillian Mawson has spent years collecting the stories of former evacuees. This book includes personal memories from more than 100 child evacuees, as well as their teachers and foster parents. Told in their own words, these accounts reveal what it was like to settle into a new home with strangers, often staying for years. While many enjoyed life in the countryside, some escaping inner-city poverty, others endured ill-treatment and homesickness.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain initiated Operation Pied Piper, evacuating more than three million civilians out of areas considered prime targets for bombing. It was the largest ever transportation of people across Britain, and most of those moved to safety in the countryside were schoolchildren.

Social historian Gillian Mawson has spent years collecting the stories of former evacuees. This book includes personal memories from more than 100 child evacuees, as well as their teachers and foster parents. Told in their own words, these accounts reveal what it was like to settle into a new home with strangers, often staying for years. While many enjoyed life in the countryside, some escaping inner-city poverty, others endured ill-treatment and homesickness.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781473849327Subtopic

British HistoryChapter One

Arrivals and Departures: Embarking on Evacuation

These stories focus on evacuees’ poignant accounts of leaving their homes and arriving in evacuation reception areas. Some of the evacuees I interviewed still possess the evacuation instructions that they were given by their teachers. On the outbreak of war, parents were told to refer to the evacuation instructions and prepare a bag or rucksack containing the listed items that their child would need, should the call for evacuation arise.

Every day children would set off for school with their rucksack and a sandwich, in readiness for evacuation. Many children did not know if they would return home that day, whilst others had no real understanding of what evacuation actually meant. As they waved goodbye to their children each morning, parents had no idea whether they would return home from school that afternoon.

Guernsey evacuees John Helyer, Hazel Hall and June le Page leaving Bury, Lancashire in 1945. (Courtesy of John Helyer)

Schools held regular evacuation drills and children would spend hours, standing in lines in the playground, being counted, having their identity labels checked, and the contents of their bags examined. Some even practised the walk to their nearest railway station. Children were also told to bring a stamped postcard with their home address clearly written on it, so that they could send their new address to their parents once they reached their new billet. They were instructed to write only cheerful messages that would not upset their parents, such as ‘Dear Mum and Dad, I am in a good home here, and happy’.

According to James Roffey in Send them to Safety, this had tragic consequences for one little boy. The young evacuee posted a card home from his new billet, then went for a walk, but in the unfamiliar surroundings, he somehow fell into the canal, where he drowned. His family were advised of his death that evening, but the next morning his postcard arrived with its cheerful inscription, ‘Dear Mum & Dad, I am very happy here, don’t worry about me.’

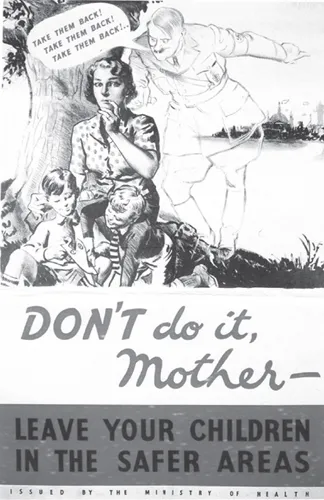

Government propaganda poster, urging mothers to have their children evacuated. (Author’s collection)

In the early hours of 1 September 1939 the government’s carefully devised plans for evacuation were put into operation, and the majority of the schools, teachers and escorts were moved before war was declared on 3 September 1939. As each school was evacuated, some parents found out at the very last moment, and ran to the railway station in order to say goodbye to their children. In some areas, such as Dagenham, long lines of children snaked through the streets, heading towards the ports where paddle steamers ships would transport them to safer areas.

As each school departed, a notice was hung upon its gates, announcing the destination to which the schoolchildren had been evacuated. When their children did not return home at the usual time, mothers gathered at the school gates to read these short, stark notices.

Meanwhile, when the evacuees arrived at the designated reception areas they were taken to public buildings, such as church halls and schools, where they were registered and given something to eat. Some received a carrier bag containing food items intended for their new foster parents. However, not all of the children understood this and many immediately began to consume the contents.

A young evacuee finds comfort with her teddy bear beside a suitcase. (Courtesy of the Kent Messenger Group)

Finally, the evacuees were allocated to local families, usually in small groups or ones and twos. Siblings and, in some cases, mothers and their children, were often separated, and many must have spent that first night in a new place suffering badly from homesickness.

Saying Goodbye

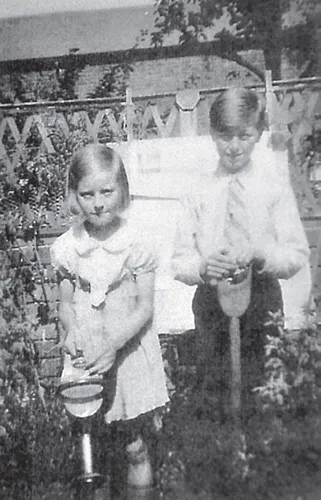

Jean Noble, then aged seven, and her brother Bern, aged ten, were evacuated from Stoke Newington, London, to Reading in 1939.

‘I arrived home one day from school and found we had a visitor, my grandmother’s brother Frank, who lived with his daughter and her husband in Reading. To prevent us being billeted with strangers, they were offering to take us in. A few days later, we set off for Waterloo Railway Station with Mum.

‘The noise in the concourse was tremendous, with hundreds of bewildered children, panicking parents and agitated teachers. The crush was frightening, with children trying to keep connected to their own little group while being pushed and jostled towards various railway platforms. I held tightly on to Mum’s coat as she juggled with two suitcases and two children. Because we were not leaving with a school she was allowed to come onto the platform, where she reminded me that my brother was in charge. On reflection, for a ten-year-old he took his responsibility seriously and was stoical, not showing any sign of distress.

Jean Noble (left) and her brother Bern (right), were lucky enough to be evacuated to family members, rather than strangers. (Courtesy of Jean Noble)

‘Mum found us a carriage with seats by the window and waited on the platform, calling out last minute instructions to behave ourselves. Then, as the train started to pull away, I saw my mother’s face crumple in abject misery and her floodgate of tears opened, which set me off and I grizzled for the rest of the journey. I realise now that we were lucky, because most of the other children on the train were travelling to some unknown destination in the West Country, and would be boarded with complete strangers.’

Letter to householders sent out by the local authorities in Cornwall, informing them ‘you must take in evacuees’. (Courtesy of Cornwall Council)

Jean and Bern stayed in Reading until spring 1941, but they do not remember receiving love or comfort from their foster-mother. The only thing Jean really appreciated and wants to remember of her evacuation, was the freedom of the river and countryside which she enjoyed at the weekends.

Choosing a Billet

Vivienne Newell, then aged six and her sister Beryl, aged eight, were evacuated from Ilford to Ipswich in 1939.

‘My sister and I were fostered by a couple who didn’t want evacuees. They were told that the alternative was to billet soldiers, so they took us in. They were not unkind to us but didn’t understand how to look after young girls.

‘Beryl decided that we should move, so she and I walked across Ipswich to a house where some of our school friends were staying. The lady already had three girls of her own and two evacuees, but she allowed us to stay.

‘There were five little girls in a double bed, with three at one end and two in the other! One of us left a doll behind at the previous billet, but their grown up son came and handed it over to us. I don’t know if they were being...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Websites on Evacuation

- The Evacuees Reunion Association

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evacuees by Gillian Mawson in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.