![]()

Chapter One

The beginning

Plaque on the drill hall, Huddersfield

Whilst the news in 1914 was more concerned with the troubles in Ireland, there were still reports about the murmurings and manoeuvrings on the continent. As tension mounted, the government stated that there were no treaties that bound England to fight for any other country – neutrality was a definite option. The Huddersfield Chronicle took a slightly different view, commenting that in the event of war Britain would ‘strike with the same strong arm and same undivided force which has always made its stroke so potent a factor in European politics’. (HC, 1 August 1914)

On 3 August 1914 one headline in the Huddersfield Examiner announced that ‘Germany has declared War on Russia’, but also commented that ‘it is clear there is no obligation [on England] to fight for France if war should break out …’

The next day England declared war on Germany. Not in order to support France or Russia but because Germany completely ignored Belgium’s refusal to allow German troops to march through its country and England had guaranteed Belgium’s right to neutrality.

Stranded on the continent

Many people had been accidentally caught up in the war. Huddersfield firms traded all over the world and often had close contact with their European counterparts, especially in Germany. Mrs Sarah Hellowell Carter, of Marsh, had been in Frankfurt staying with her son Edwin, who was there on business, and said on her eventual return that the German military were showing greater activity around the towns and everywhere patriotic songs were being played. The English vice-consul had advised her to leave and she’d immediately gone to Cologne, where there was much confusion with tourists from all over the world trying to escape from the threatened war. Then she’d managed to meet a Thomas Cook’s tour, travelled with them in what she described as a cattle truck to the Belgian border and thence to Ostend where she caught a boat home. Even the mayor’s family was caught up in the problem. His eldest daughter Emma Blamires was in school in Versailles and she too was forced to leave, being woken at 4 am on a Sunday and not reaching London until midnight after a traumatic journey.

Herbert Brook, a teacher, had an even more exciting time. He’d been in Germany to see a friend, John Falck, another Huddersfield teacher who had won the Martin-Fisher Travelling Scholarship and was working in Cologne. Brook was told to leave the country. Despite all the bridges being guarded and everyone being scrutinised carefully, he began his journey and managed to get to Neuss. He then set off from Cologne on the bank holiday and reached Dolheim, where he and a number of others were ‘hustled out of the train and into a large waiting room crowded with German soldiers’. (HE, 18 August 1914) He was advised to walk to the frontier about a mile away, but there he was stopped and ordered back to Dolheim to get a passport from the German commander. He fell in with two Englishmen and a couple of Belgians and together they returned to Munchen Gladbach, where they were arrested. Although the Belgians had passports countersigned by the police they were still taken to prison, but Brook and his companions were advised to walk to Dusseldorf and try to get to Drusberg. They hired a car but were again arrested and the car searched for bombs.

At the British consul in Dusseldorf they met another dozen stranded Englishmen. By this time Brook had only £1 10/- (£1.50) left but paid five shillings (25p) for a passport. Eventually they got to Drusberg and stayed in lodgings, where they were kindly treated by the German landlord. Despite not venturing out on to the streets, they were arrested again and taken to the Oberbergermeister, or lord mayor, who eventually gave them papers to allow them to cross the Dutch frontier into Holland at Emmerich.

On the way there the train was stopped and the men got out. The one who spoke the best German went to ask a German soldier what was happening and, being mistaken for German reserve officers, they were cheered by the German soldiers. Though they had to get out again at Wesel and were treated rather roughly, they eventually reached Arnheim, thence to Utrecht, then Rotterdam and The Hague, where other refugees were congregating, and finally to Harwich and home. Brook admitted he was surprised to have been allowed to leave since Germany had already announced that no French or English between the ages of 16 and 45 were allowed to leave the country, and all the three men were young adults.

Civilian internees

Ruhleben Camp had been set up in a racetrack, using the grandstand buildings to house internees, including any civilians who had been in Germany or on merchant ships at the outbreak of war. Edwin Hellowell Carter, whose mother had had a narrow escape from the country, was taken to Ruhleben near Berlin. Many merchant ships were impounded in the docks and the crews taken to civilian camps.

In December 1914, the mayor, Joseph Blamires, received a postcard from Germany from Barrack No 3, Englanderlager at Ruhleben Spandau internment camp. The Huddersfield inmates, who included William Kemp, James Blackburn, Henry Shaw, Harold Eastwood, J. Douglas Walker, William Clarke, John Dyson and Wilson Cockroft, sent the card to let everyone know they were alive and well, wished all a Happy Christmas and ‘a brighter New Year’. The following year a list of prisoners at the camp was obtained which, as well as the lads who sent the postcard, now included three brothers, Harry, Fred and George Emmett, from Rock Villa, Scissett, and G. Crosland, son of Guy Crosland, who was a well-known golfer in the area. The group had got together with many other Yorkshire internees to form their own Yorkshire Society.

They described the conditions as getting better after some intervention from the Foreign Office. The work of improving the conditions in the camp was done by the internees themselves who were, by and large, left to their own devices by the German guards. The British government sent allowances of 5/- (25p) per week to the men there so they had managed to set up shops and businesses, which seemed to be thriving. Gifts from home, however, were not only welcome but needed as food was still in short supply. Whatever the conditions in the camp, at least their families knew they were alive and likely to survive the war.

There seemed to be little difficulty in getting letters back home and details regularly appeared in the newspapers. According to the Huddersfield Examiner on 26 August 1915, the men had a lot of time on their hands and so organised various events and businesses. This included a theatre named the Frivolity and a newspaper. They also held mock elections, in which the Women’s Suffrage party won by a large majority.

In December 1915, John William Dyson was allowed home because of his age – 53. He had been working in Germany for nearly twenty years as a power loom tuner but had been arrested in Silesia before being sent to Ruhleben.

They’re here

Almost as soon as war was declared, people were on the lookout for spies and aliens. At Crosland Moor a whole group of spies got off the tram and proceeded to chalk up a ‘curious message’ on the pavement. (HE, 14 August 1914) A guard was set over this message until the police could arrive, since it was obvious (to the rumour mongers) that these were Germans about to blow up the banks or else poison the local reservoir. It was only later that someone arrived and was able to translate the message, which was written in Esperanto. The group were apparently Dutch and the message was to the rest of the group who were arriving later. Everyone was able to calm down and told to ‘keep cool’.

Later in the year all aliens were in fact interned and searches made amongst the many Belgian refugees, just in case there really were spies amongst them.

Britain had had little experience of wars being fought on its own land – for centuries battles had been on the Continent or in distant parts of the empire. In December 1914, the war was suddenly brought home to many people when the Germans bombarded Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby. C.H. Crowther, a Huddersfield magistrate and director of Middlemost Brothers Ltd, had been in Scarborough during the shelling and described the damage to the buildings with ‘stones flying around’. Others left Scarborough on the earliest available trains, coming to Huddersfield to stay with relatives, and described how the fishing fleet had only just returned to harbour when the bombardment started, leaving many trawlers damaged. (HE, 16 December 1914) The loss of life, particularly that of women and children, was seen as an example of German barbarism and confirmed, for many, the need to fight against them.

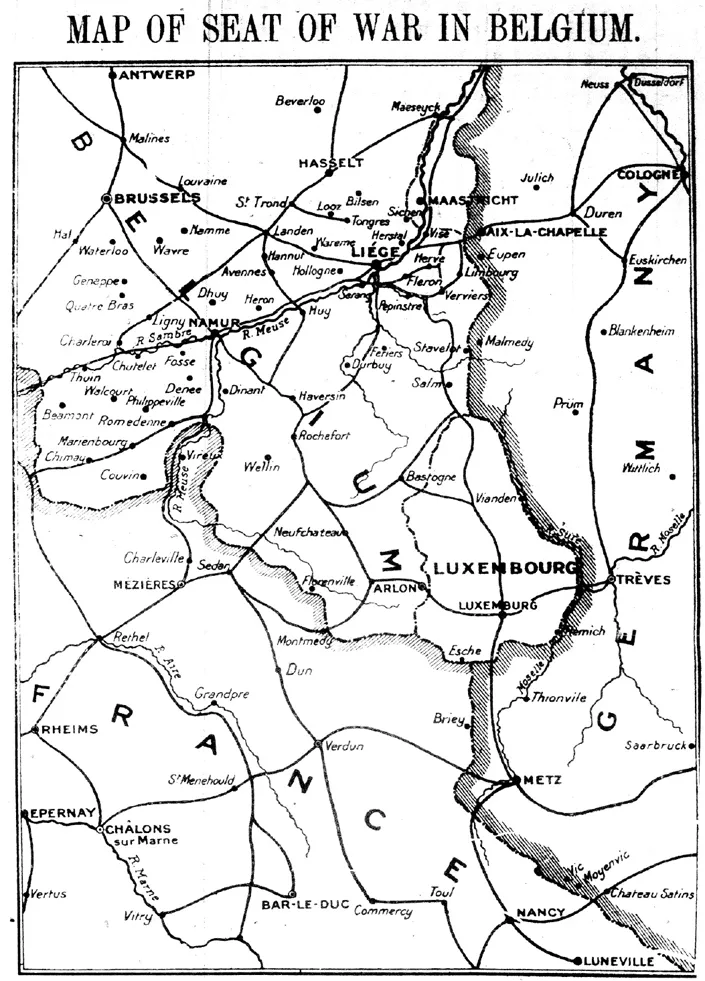

Workers’ education

On 22 August 1914, the Huddersfield Chronicle published a map of Belgium to show everyone where the events were taking place. The Huddersfield Workers’ Educational Association set up meetings in the technical college to provide lectures and tutorials of various kinds to help people try to understand the background to the war. There was, they said, a ‘need for an educated democracy in order that a proper settlement of the European war might be made possible’. (KC648/1) Other subjects included talks about the various countries involved including Germany, France, Russia and Serbia. Some of the Belgian refugees later gave classes in French and study circles were set up in outlying districts. The empire was not forgotten – Mr Hydari gave a lecture on ‘Indian Aspirations’, whilst Mr Wilson’s talk was about ‘Colour and Labour in South Africa’. People were very interested in what was going on in the world and in the changing patterns of society.

Area of War, Belgium

Throughout the war the town and parish councils had to take on many more jobs, despite the loss of many of their workers to the forces. They became responsible for war relief, war savings, food control, fuel control, providing for the Belgian refugees, and ensuring the correct running of military service tribunals, etc. ‘Everybody almost was engaged in sending out comforts to the troops, in organising and serving on Relief Committees of one kind or another. Hospitality was shown to many Belgian refugees and in ways too numerous to mention people were supporting the National Cause.’ (E. Lockwood, Colne Valley Folk)

Belgian refugees

At the very beginning of the war the Germans had planned to march quickly, taking the French army by surprise and forcing them to surrender in what they hoped would be a repetition of a previous war between those two countries, which Germany had won conclusively. To keep the element of surprise, they chose to attack through the neutral country of Belgium. The German Slieffen Plan was a meticulously worked out timetable of events, specifying the number of days allowed for winning each objective. It didn’t, however, take into account the determined resistance of the Belgians, whose tiny army held up the Germans for over a month, attacking supplies and causing delays that gave the British and French time to mobilise their own armies. The German invasion of a neutral country also caused worldwide condemnation from other countries, ensuring greater support for the Allies.

As Germany advanced, the people of Belgium fled. Fleeing first to neutral Holland, many arrived in Britain with nothing but the clothes they had on. Towns all over the country took in the refugees and raised funds to provide them with homes, furniture, food and clothing.

Not just Huddersfield but also the outlying villages undertook to look after the refugees. Cottages or houses were found for families, and each village became responsible for finding at least £1 per week, per family, for food. Flora Lockwood, in her diaries, commented that when the first Belgians arrived in November there was great excitement, with Belgian flags flying to welcome them. They were taken to the Town Hall for tea before going to their accommodation. Most were women and children from Antwerp, whose husbands were fighting in Belgium. One woman had five sons still there.

Two families, Mr and Mrs Peters and their son and Mr and Mrs van Dessel, whose baby girl had died of pneumonia on the journey, went to cottages in Kirkburton, while a further sixty refugees were housed in Royds Hall, which had been cleaned, repaired and equipped by volunteers from Huddersfield.

Many of the refugees told of the great atrocities committed by the Germans and of the bombing of Malines, where hardly a building was left standing. They had had to walk from their homes to Antwerp, then journey through Holland before reaching England and finally Huddersfield. Unfortunately most of them spoke Flemish, so communications were difficult. But a few spoke French and acted as interpreters.

Flora Lockwood noted in her diary that there were many adjustments to make as destitute people came in and had to adjust to a new way of life, while some of their ‘hosts’ felt that ‘they don’t seem contented with aught we do for them’. When she went to visit a house that was being used by a number of Belgian families, she found them quite comfortable, with ‘some round the fire, some playing cards and smoking and others playing a strident accordion’. But one of the helpers, Mr Lodge, told her that one had said to him ‘we like a sausage to us tea’. Mr Lodge returned ‘so do we, but we are glad to get it for us dinner and working for it, an all!’ (War Diaries of Flora Lockwood)

There were frequent disputes that Flora had to try and sort out, as she was one of the few who spoke French. Later, many of the Belgians found work in local mills and were able to support themselves, though this too sometimes brought occasional snide comments from locals who felt that Belgian men should have been fighting with the Belgian Army to secure the freedom of their own country. On the whole, however, there was great sympathy for the families who had lost so much and funds were always forthcoming to help them, with little presents and fruitcake at Christmas.

The Huddersfield Examiner wrote, on 11 December 1914, that ‘over three thousand pounds’ had already been raised to help the refugees. ‘Without making comparison with other towns,’ it continued, ‘we may heartily congratulate the Huddersfield district on having so freely and generously recognised the claim not of humanity only but of the heroic valour which held the hosts of Germany at bay long enough to enable the stronger Allies to organise an effectual resistance …’

Despite the reasonably harmonious feelings between the Belgians and Brits, not everything went according to plan. In January 1915, Charles Louis Wonters, a Belgian refugee, was in court for being drunk and refusing to leave the Royal Oak Inn, in Paddock, on New Year’s Day. As he only spoke Flemish an interpreter, Mr G. P. de Schryvere, had to be brought in. ...