- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Picton's Division at Waterloo

About this book

In the two hundred years since the Battle of Waterloo countless studies examining almost every aspect of this momentous event have been published narratives of the campaign, graphic accounts of key stages in the fighting or of the role played by a regiment or by an individual who was there - an eyewitness. But what has not been written is an in-depth study of a division, one of the larger formations that made up the armies on that decisive battlefield, and that is exactly the purpose of Philip Haythornthwaites original and highly readable new book. He concentrates on the famous Fifth Division, commanded by Sir Thomas Picton, which was a key element in Wellingtons Reserve. The experiences of this division form a microcosm of those of the entire army. Vividly, using a range of first-hand accounts, the author describes the actions of the officers and men throughout this short, intense campaign, in particular their involvement the fighting at Quatre Bras and at Waterloo itself.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

‘The Rocks of the North’

(United Service Journal 1834)

(United Service Journal 1834)

Waterloo

The position upon which the army had drawn up was as suitable as any for the defensive battle that Wellington knew he would have to fight. An action of manoeuvre was out of the question: he realized that, with his army of raw troops interspersed by veterans, he had to hold until Blücher’s Prussians could come up from the east and exert pressure on Napoleon’s right flank. Without the presence of the Prussians on Wellington’s far left, with the expectation that they would assist, the duke would surely never have fought where he did, and indeed advised his civilian friends in Brussels to prepare to flee to Antwerp should circumstances force him to ‘uncover’ the city. However, if he did intend the fight, the position along the ridge at Mont St. Jean was as good as any.

Wellington’s front line was roughly along a road running west to east, between the villages of Brain l’Alleud in the east and Ohain in the west, and sometimes referred to as the Ohain road. It was lined with hedges and in places slightly sunken, although not with the ‘ravine’ sometimes described. Intersecting this road, and dividing Wellington’s position roughly in half, was the Charleroi– Brussels highway, which across the Ohain road ran northwards to Brussels, passing alongside the farm and village of Mont St. Jean and, further north, the village of Waterloo. The Mont St. Jean ridge sloped away to the south, so that attackers would have to climb it, from a depression between it and the parallel ridge further south, that upon which Napoleon was to establish his position. The Mont St. Jean ridge sloped away more gently to the north, providing a ‘reverse slope’ behind the front line that was a feature of Wellington’s preferred tactic, of concealing the bulk of his army from the enemy’s view, behind the crest of a ridge, thus protecting his own troops from artillery fire and also making the enemy unsure of his position, and thus difficult to decide when their attacking columns should deploy into line for the close-quarter combat. In this case, the task of the attacking French would be made even more difficult by the tall standing crops on parts of the field, further obscuring their enemy.

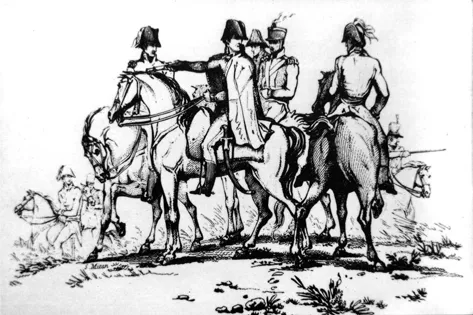

Wellington and his staff at Waterloo. The duke is shown wearing his cape, and while most of his officers wear the staff uniform, the aide in the shako and the 1812 light dragoon uniform must be intended to represent his ADC, Lord George Lennox, son of the Duke of Richmond, a lieutenant in the 9th Light Dragoons. (Engraving by S. Mitan after George Jones, published 1817)

Wellington’s front line was anchored by three strongpoints. At the extreme left flank were the hamlets of Papelotte, La Haie, Smohain and Frischermont; throughout the day they were held by Netherlands troops, without the involvement of any British units. The extreme right of the line was bolstered by the chateau and walled farm of Hougoumont, which was to form one of the focal points of the battle in blocking a route that Napoleon could have used in attempting to turn Wellington’s flank. The chateau and grounds were to be held with the greatest determination and heroism by the 2nd and 3rd Foot Guards from the 1st Division, with some lesser contingents. The third strongpoint was in advance of the centre of the line, the farmhouse and grounds of La Haye Sainte, which abutted the Charleroi–Brussels highway, with an excavation known as the gravel or sandpit on the opposite side of the highway and a short way north, which was level with the road on the west side but banked on the other three sides. This feature was to involve men from the 5th Division in the approaching battle.

To the rear of Wellington’s position was the Forêt de Soignes, which extended almost all the way from Waterloo to the outskirts of Brussels. A very short time after the Battle of Waterloo Sir Walter Scott described its appearance, when approaching Wellington’s position from Brussels:

a wood composed of beech-trees growing uncommonly close together [which] is traversed by the road from Brussels, a broad long causeway, which, upon issuing from the wood, reaches the small village of Waterloo. Beyond this point, the wood assumes a more straggling and dispersed appearance, until about a mile further, where at an extended ridge, called the heights of Mount St. John, from a farm-house situated upon the Brussels road, the trees almost entirely disappear.1

The Forêt de Soignes: the thick woodland in the rear of Wellington’s position at Mont St. Jean, which by conventional wisdom could have hindered a withdrawal; but the duke and others believed that if the army had been driven off the ridge, they could have held the woods against all comers. (Engraving by and after J. Rouse, published 1816)

Conventional military wisdom held that giving battle in front of so thick a wood was courting disaster, as it would greatly hinder a retreat; but this was clearly not in Wellington’s mind, as Scott recorded. When the duke was questioned on this point he remarked that if they had been forced to retreat, they would have gone no further than the trees. His questioner asked ‘if the wood also was forced?’; ‘No, no, they could never have so beaten us, but we could have made good the wood against them,’2 and the opinion that they could never have been driven from the wood was echoed by other experienced campaigners.

The rain abated by early morning, and the army began to shake itself into fighting order. The line presented what an officer of the Royal Scots described as ‘dismal to a degree, and men and officers, with their dirty clothes, and chins unshorn, had a rather disconsolate look in the morning; however, the sun broke out, and brightened the scene a little, and we were aware of what was coming, which probably removed any little stiffness left by the wet and cold of the night.’3 Many must have felt like Robertson of the 92nd: ‘We were aroused by daylight, on the morning of the 18th, and ordered to stand to our arms, till the line should be reconstructed. During the time I never felt colder in my life; every one of us was shaking like an aspen leaf ... we seemed as if under a fit of ague ...’4 (The stand-to at dawn, as at twilight, was a common practice; enemy attacks could come almost unrecognized in the half-light, and it was only safe to relax, to use a nautical expression, when a goose could be seen at a mile.)

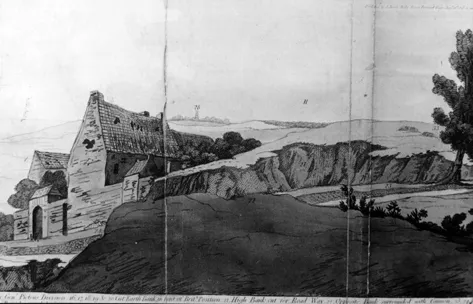

La Haye Sainte: an early view, evidently drawn by Charlotte Waldie’s sister Jane, later Watts, showing the damage of battle. The excavation or ‘sandpit’ and higher ground at right is that defended by the 1/95th, at the right flank of the 5th Division’s position. (Print published by Booth, 1816)

The certainty of being ‘aware of what was coming’ to some only became obvious as the morning wore on. John Kincaid of the 1/95th, even though he was the battalion adjutant, could not be sure that the army was going to stand until an order was received to stack reserve ammunition in a safe place behind the line, and to send to the rear, and thus to a place of relative safety, any baggage and draught animals. This made it certain that Wellington was going to accept a battle on the ground where the army had spent the night. The despatch to the rear of any regimental baggage removed a number of officers, NCOs and men from the firing line, weakening even further the more badly hit battalions, but it was a necessary precaution to prevent the baggage from being plundered while the majority were otherwise engaged. The numbers of men so detached is impossible to ascertain with precision, as some units continued to count them as ‘present’ while others even denied such individuals the Waterloo Medal when it was issued. There did arrive, however, a welcome reinforcement noticed especially by the 5th Division: the brigade of Sir John Lambert came up after marching determinedly from Brussels, having returned only recently from North America. They received some gentle mockery from the 5th Division on account of their smart, clean uniforms, contrasting with the stained, mud-caked appearance of the 5th. The officer quoted above described how the whole line became active as the sky lightened on Sunday, 18 June:

a moving mass of human beings – soldiers cleaning their arms and examining the locks, multitudes carrying wood, water, and straw from the village and farm of Mont St. Jean; others making large fires to dry their clothes, or roasting little pieces of meat upon the end of a stick or ramrod, thrust among the embers; a few bundles of straw had been procured, upon which our officers were seated. Though nearly ankle-deep in mud, they were generally gay, and apparently thinking of everything but the approaching combat, which snapped the thread of existence of so many of them.

He noted that the Peninsular veterans always had a little food remaining in their haversacks, and above all attended to their weapons: ‘The sound of preparation of so large a body, about 90,000 men, reminded me forcibly of the distant murmur of the waves of the sea, beating against some iron-bound coast.’

A number of officers who had been wounded quite severely at Quatre Bras had nevertheless marched with their battalions on the previous day, but its exertions made it impossible for them to continue any longer; so with much regret the most fragile among them were persuaded to retire to Brussels if they were so ill as to be unable to perform their duty. To them were entrusted messages from those who remained behind, notably brief wills, ‘done without the smallest appearance of despondency; but Kempt’s and Pack’s brigades had got such a mauling of the 16th, that they thought it well to have all straight. The wounded officers shook hands, and departed for Brussels.’5

James Anton of the 42nd described how weapons were put in order: old charges extracted, powder washed from the priming pans, the muskets then dried and the locks oiled. There was accommodation in the cartridge box for spare flints, and it was usual before an action to fix a new, sharp flint into the jaws of the cock to minimize misfires. Amid all this activity, some units at last received rations. James Hope of the 92nd, who had eaten nothing for two days, had roasted a steak on a ramrod over his fire, but noted that after so wretched a night many soldiers seemed to have no appetite; until there was an issue of spirits, ‘which tended to keep our drooping spirits from sinking under our accumulated load of misery ... we lighted fires, pulled off our jackets, shoes, and stockings, dried them, and endeavoured to make ourselves comfortable.’6 Some even began to make improvised shelters, and Hope had just fallen asleep in one when roused by bugles sounding the assembly.

The position of the 5th Division, on which they were to fight, was a crucial part of the line, occupying most of the left of Wellington’s line; despite the mauling they had received at Quatre Bras it is likely that it was thought that only the most reliable of troops could be entrusted with such responsibility. The division’s position extended from the eastern edge of the Charleroi– Brussels highway, eastwards to the extreme left flank; the only troops initially further to the left were the light cavalry brigades of Sir John Vandeleur and Sir Hussey Vivian, with Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar’s Netherlandish troops in advance and to the east of the main line, in the Papelotte/La Haie/Smohain/Frischermont complex. Kempt’s Brigade occupied the right (western edge) of the division’s position, with Pack’s Brigade further east. Between the two, and originally forward of them, was the Dutch–Belgian brigade of General Major W.F., Count van Bylandt (or Bijlandt; in British service he appeared in the Army List as ‘Count William Byland’). Further east from Pack’s Brigade was Best’s Hanoverian brigade, and asVincke’s Brigade had finally joined the 5th Division, to which it had been allocated, it was posted further east still, so that it was the infantry formation on the extreme left of Wellington’s army.

Battle of Waterloo: the opening dispositions, with Picton’s Division to the east of the Brussels–Charleroi highway. The cavalry formations behind the infantry line include Ponsonby’s Union Brigade and Somerset’s Household Brigade.

The individual battalions did not remain static throughout the battle, but in general Kempt’s Brigade was arrayed with the 1/95th on the extreme right, against the highway, then from west to east the 32nd, 79th, and 28th; then Bylandt’s; then Pack’s, from west to east the 1st, 42nd, 92nd and 44th. The 1/95th was not initially deployed as a solid body, but as appropriate for the most expert skirmishers in the army, two companies under Major Jonathan Leach were thrown forward to hold the sandpit by the side of La Haye Sainte to support its garrison of King’s German Legion 2nd Light Battalion, with Captain William Johnstone’s company in support. The remaining three companies of the 1/95th lined the Ohain road east of the Brussels highway. In addition, a party under Lieutenant George Simmons was sent to cut wood to form an abattis (barricade) across the highway, to assist in the defence of the area of the sandpit.

The troops immediately to the west of the highway, thus holding the line on Picton’s right flank, were the King’s German Legion brigade of Colonel Christian von Ompteda, and to his right the Hanoverians of Count Kielmansegge. To the rear of the 5th Division was positioned Sir William Ponsonby’s 2nd Cavalry Brigade, known as the ‘Union’ Brigade from its composition of English (1st Royal), Scottish (2nd Royal North British) and Irish (6th Inniskilling) Dragoon regiments. In the corresponding place behind Ompteda and Kielmansegge was Lord Edward Somerset’s 1st Cavalry or Household Brigade, comprising the 1st and 2nd Life Guards, Royal Horse Guards and 1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards.

Waterloo: French cavalry attacks part of the line held by the 5th Division, with La Haye Sainte at left and the sandpit in mid-ground, centre. (Print by T. Sutherland after William Heath)

The only artillery capable of indirect fire – i.e. over the heads of friendly troops – were howitzers, of which each company or horse artillery troop had only one, so that artillery had to be positioned in direct line of sight of the enemy. This meant that the divisional artillery companies had to be positioned among or in front of the infantry, which was the case with the two companies attached to the 5th Division. It was usual for the pieces in the gun line to have sufficient distance between them to permit infantry to advance or retire through the line without becoming disordered, and for only the guns to be in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

- The 1815 Campaign

- The Divisional System

- Sir Thomas Picton

- The British Infantry

- In Brussels

- The Assembly

- Quatre Bras

- Withdrawal

- Waterloo

- Reputations

- Notes

- Appendices

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Picton's Division at Waterloo by Philip Haythornthwaite in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.