![]()

1. DAY OF THE BUSHIDO

It is considered, therefore, in some quarters, that Malaya is in real danger of finding herself engaged in war during the next few months.

(Aberdeen Journal, 31 January 1941)

Capitalising on the internal ideological conflict in China between the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist forces under Mao Zedong, the Imperial armies of Japan invaded Manchuria in September 1931. By the end of 1937, Peking, Nanking and the port city of Shanghai had fallen to the Japanese, pushing Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek ever south.

In July 1940, Japan took French Indochina, and in a territorial trade-off with the French Vichy regime, extended its influence westwards into neighbouring Siam. Only became Thailand in 1949.

MALAYA’ S DEFENCES

Let us examine the possibilities in a Japanese attack on Malaya, for Japan could never hold any part of the Indies unless she held Malaya too.

There are three usual forms of attack – land, sea, and air. An attack overland, supposing the Japanese had made their way from Indo-China into Thailand and down the Kra isthmus, can practically be ruled out. Malaya in its 600 miles of length has two railways and one main road, routes that easily can be rendered impassable.

Taking a mechanised army through the dense Malayan jungle will be about as difficult as driving a child’s toy clock-work motor car through a concrete wall.

Suppose the infantry footslog along the jungle trails. Why, the primitive Sakai of the Malaysian hinterland, who have never heard of tanks or Tommy guns, using their blow pipes and poisoned darts from the forest cover, could take a sickening toll of an invader: and what if the trees hid well-armed British troops.

To make a sea attack Japanese warships must travel a long way in British or American patrolled waters. The supply routes from Japan pass uncomfortably close to the American bases in the Philippines.

Singapore is within range of Japanese bombers – until they meet our fighters. The landing of troops by air is another difficult problem, for you cannot land aeroplanes, or, for that matter, parachutists, on tree tops, and Malaya is a country of trees with very few open spaces.

And while enumerating the natural difficulties that confront a Japanese assault on Malaya we are not forgetful of the man-made difficulties – the increased strength of our forces there.

(Western Mail, Saturday, 2 August 1941)

The Japanese Tenth Army parades after the bloody taking of the capital of China’s eastern Jiangsu province, Nanking (Nanjing), in December 1937.

British governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Shenton Thomas, warned Britain in February 1940 that ‘active war is more close to the shore of Malaya than ever before’. In spite of the vulnerability of Singapore’s ‘back-door … everybody knows of the formidable defences of that focal point of the Empire’s defences. Singapore is impregnable from the sea, as combined naval, aerial, and army manoeuvres before the war proved. Now the mainland of Malaya, which lies behind it, is rapidly being placed in a state of defence, and would prove a formidable obstacle to any attacker’.

For much of 1941, while apprehensively monitoring Japanese expansionism in the region, Britain continued to bolster her fighting capacity in Malaya. In August, the commander of British forces in China, Canadian-born Major General Arthur E. Grasset, confidently said, ‘It is my considered opinion that unless she becomes really desperate, Japan will not be so rash as to fight Britain or the United States.’

Shortly after midnight on 8 December 1941 (local time), and just before the attack on Pearl Harbor, a Japanese attack force drawn from Lieutenant General Tomoyuki’s Twenty-fifth Army, landed at Kota Bharu on Malaya’s north-east coast. Basking in the morale-boosting sinking of the Royal Navy’s battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse by Japanese bombers off Kuantan in the South China Sea, the Japanese forces advanced southwards. By the end of January 1942, the whole of Malaya had fallen to the Japanese.

For the next three years, British and Commonwealth prisoners of war and the civilian Malay population suffered inhuman depravation and degradation, and a mindless pogrom of mass executions. The occupying power’s unfaltering belief in the godhead emperor and a revived Bushido code of conduct legitimised atrocious actions in the name of moral purity. There was honour in death and absolute shame in weakness and failure. The act of seppuku – ritual suicide – was the honourable and ultimate act of atonement by the Samurai warrior who had failed the moral code of Bushido.

The uniformed disciple of the code therefore possessed an inculcated conviction that death inflicted on oneself or another to satisfy the premises of the Bushido code, was beyond question.

‘AUSSIES’ IN MALAYA HAVE RILED JAPAN

Thousands of cheering Australian troops have poured into Singapore, Britain’s bastion in the Far East, in the last few days.

They formed the biggest force ever to arrive in Malaya in a single convoy. Their voyage and their landing was without incident.

When Japan heard the news there was evidence how unwelcome it was. ‘Far from stabilising the situation in the Far East, the British action is apparently an attempt to create suspicion and distrust,’ bemoaned a Japanese military spokesman in Shanghai. To cap the news of the Australians’ arrival came a well-timed announcement that the Royal Air Force had been greatly strengthened in the Far East, too.

I watched the Australian troops arrive at Singapore to the strains of ‘Roll Out the Barrel’, and the heartfelt cheers of thousands of spectators on the quaysides (writes the B.U.P. correspondent there).

As the Australians disembarked, the watchers on land could see how complete a unit it was. Not only was there infantry, artillery and signallers, but nursing units and all ancillary services, supply depots, an Australian general hospital, artillery regiments equipped with the most modern howitzers and field guns (manufactured in Australia), anti-tank units, many fully mechanised infantry battalions, and an Australian Army Service Corps unit with its own transport.

The men had been trained as storm troops and it can be safely said that if they were called upon to defend this outpost of Australia they would fight as their fathers did in Gallipoli, France and Palestine, and as their brothers had recently done in Libya.

(Daily Record, Thursday, 20 February 1941)

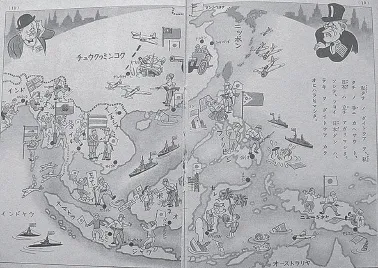

Japanese Asian propaganda poster 1943.

The anti-Japanese ethnic Chinese in Malaya, seen as a direct threat to the will of the emperor, had to be eliminated. The Sook Ching (purge through cleansing) genocide, centred in Singapore on the tip of the Malay Peninsula, spilled north. Military police of the Japanese occupation army – kempeitai – zealously massacred an estimated 100,000 ethnic Chinese.

The British Special Operations Executive formed Force 136, headquartered in Ceylon and responsible for training and arming anti-Japanese resistance movements in the Southeast Asia theatre. Early in the Japanese invasion, Captain Freddie Chapman, an experienced mountaineer and adventurer, joined the Special Training School 101 (STS 101), and for eighteen months he had to endure hardship, hunger and disease, living with Communist Chinese guerrillas in the Malayan jungles, eluding the Japanese. Eventually, in 1945, the indomitable Chapman escaped from Malaya on board the submarine HMS Statesman.

It was only then that Chapman’s jungle sojourn could be shared with the British public. On 20 September 1945, the British Daily Mirror carried a report by journalist George McCarthy:

From the time Malaya fell into the hands of the Japanese in December 1941, a party of British-led guerrillas carried on the war from their secret fortresses deep in the heart of the jungle.

There, in one of the loneliest places on earth they made friends with the aboriginal natives – the Sakai – a people so shy that they never venture into towns or villages.

It was among these people who still hunt with blowpipe and bow and arrow that Lieutenant Colonel Freddie Chapman, peacetime explorer and leader of the party, hid for months with the little army of Chinese guerrillas he had trained.

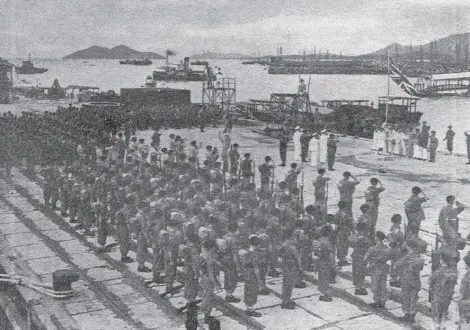

The Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army MPAJA at a disbanding ceremony in December 1945. (Source The War Illustrated)

The tribesmen had emerged from centuries of obscurity to help a hunted army. Before they had to run, Chapman and his band, in a series of brilliant raids, had killed between 500 and 1,000 Japs, cut railways and destroyed transport behind the enemy lines.

With the Sakai, Chapman and his men learned jungle tricks and taught the Sakai some in return.

In 1943, Captain R.N. Broome, Malaya Civil Service, and Captain J.L.H. Davis, Malaya Police, sneaked into Malaya and joined Chapman.

Once they escaped capture by a hair’s breadth. A Chinese merchant who had befriended them was caught and tortured; their jungle camp was attacked, and their code, maps, money and medicine lost.

But they carried on. Then, early in 1945, it became necessary for British officers to leave Malaya to report. Chapman and Broome, in darkness swam out to a grounded British submarine. They made their getaway to build a new army.

And in India and Ceylon a new force was raised, which in June this year began to drop into Malaya. When the Japs surrendered, 300 men had landed, and 2,500 Chinese and Malayan guerrillas had been armed and trained.

Chapman’s Malayan legacy was a well-honed and jungle-seasoned core of Communist guerrillas who, shortly after the surrender of Japanese forces in the region, were to turn their arms and skills against the British with the objective of driving them out of Malaya.

Royal Marines of the East Indies Fleet parade on the Penang quayside at the raising of the Union Jack following the Japanese surrender in this part of the peninsula. (Source The War Illustrated)

AUSTRALIA DEMANDS LESSON FOR JAPS

A public demand throughout Australia that Japan must be taught ‘a lesson she will never forget’ has followed the publication of the Webb report on Japanese atrocities. The report has stirred up the most bitter anti-Japanese feeling in the Commonwealth, the Sydney Sun declares.

‘With comparatively weak forces in occupation of Japan the safety of captives must be the first consideration,’ says the paper. ‘Nevertheless the Japanese must learn the hard way that calamity has befallen them.’

When an Australian party flew to Sandakan, once a large Japanese prisoner-of-war centre in North Borneo, the Japanese reported that no prisoners remained alive in the camp, an Australian Army statement said today. Official Japanese figures obtained elsewhere stated that at one stage 3,726 prisoners, including 1,900 Australians, were held at Sandakan.

Allied troops were today spreading through the Japanese home islands as the demobilisation and disarming of Japanese forces went on smoothly, General MacArthur’s headquarters announced.

Hideki Tojo, the prime minister who led Japan into the war, was reported ten days ago to be alive and preparing his defence against war crime charges, according to a Tokio [sic] report.

Field Marshal Terauchi, Supreme Jap Commander, Southern Region, has had a stroke...