- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

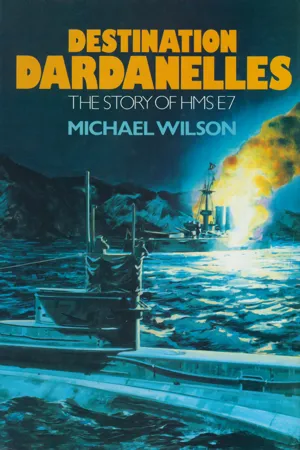

About this book

When the First World War started in 1914 the potential of the submarine as a tactical weapon was largely a matter of conjecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Destination Dardanelles by Michael Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Contents

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Countdown to War |

| 3 | Early Days |

| 4 | Battles in the Bight |

| 5 | A Time of Change |

| 6 | It Wasn’t Over by Christmas |

| 7 | 1915: A New Year |

| 8 | The Dardanelles – The Beginnings |

| 9 | The Dardanelles – The Submarines Gather |

| 10 | The New Venture |

| 11 | The Sea of Marmara |

| 12 | To the Dardanelles Again |

| Sources | |

| Bibliography | |

| Index |

1

Introduction

SINCE THE MIDDLE AGES many inventors in Europe, and later in America, had experimented with submersibles, that is ships which could travel under the sea as well as on the surface. Indeed it was man’s greatest desire either to be able to fly like the birds or to be able to travel in the sea like the fishes. But the true development of the submarine needed the impetus of two other technological advances: a satisfactory engine to propel the boat underwater, and a weapon that would justify the use of a submarine against an enemy but which would give the submarine itself a chance to survive the attack. Both these advances came in the closing years of the nineteenth century with the successful development Whitehead’ self-propelled torpedo in 1868 and the installation of an electric motor in a submarine by a Spanish naval officer in 1886.

By the end of the century the French were establishing themselves as the leading submarine power. The fact that such a force was just across the Channel from the main naval base at Portsmouth was not lost on the Admiralty for, despite the improving political relations that were to lead within a few years to the Entente Cordiale, there remained a traditional suspicion of the French surviving from centuries of warfare. It was this suspicion that finally led the Admiralty to look seriously at the requirement for submarine development in the Royal Navy.

Visiting England from America in the summer of 1900 was Mr Isaac Rice of the Electric Boat company who had built the first submarine for the US Navy and was then preparing to build seven more of a slightly improved design. The design came from John Phillip Holland who had emigrated from Ireland to America in 1873 and then produced, with no official support, a series of submarines each larger than its predecessor and of varying viability, culminating in the one purchased by the Navy and named after him. As a result of Rice’s visit it was agreed that Messrs Vickers Son & Maxim at Barrow would build five submarines for the Royal Navy on behalf of the American Company, the boats to be repeats of those being built in America.

It was a radical change of policy for the Admiralty who had been so firmly set against submarine development for so long. It may be partly excused, for it was stated in the following Naval Estimates that the submarines were being built so as to allow our destroyer commanding officers the opportunity of working against them.

A firm order was placed with Vickers in December, 1900, and Captain R. H. S. Bacon, a torpedo specialist, was sent to Barrow to oversee the work of construction. Lieutenant F. D. Arnold-Foster, another torpedo specialist, followed, destined to become the first commanding officer of the Royal Navy’s first submarine. At Barrow the work of building this new vessel was carried on in great secrecy; Arnold-Foster recalls that on arrival in the shipyard he was anxious to sight his new ship but no one seemed to have heard of any submarine being built. Eventually the boat was found in a large shed prominently marked ‘Yacht Shed’, while parts were made and delivered as ‘Pontoon Number One’.

Submarine Torpedo Boat No 1, or Holland 1 as she became known, was launched without the usual ceremonies on 2 October, 1901, and began sea trials on 15 January the following year. The other boats followed in quick succession. The submarine as a vessel of war had now taken its place in the Royal Navy, but what sort of boats were these early submarines?

The Holland class were single-hulled vessels of spindle form, that is the main ballast tanks which were filled with water to make the submarine dive were internal to the pressure hull, and the hull itself was circular in shape with the centre of all sections in a straight line. At the forward end there was a single 18in torpedo tube. There were no internal watertight bulkheads, nor any provision for crew comfort; the cluttered interior was devoted solely to the working of the submarine. A 60-cell battery powered a single electric motor giving the submarine a nominal range of 25 miles at the maximum underwater speed of about 7 knots. On the surface a 4-cylinder petrol engine was expected to give a range of some 250 miles at the maximum speed of 8 knots, and was also used to charge the battery. A single rudder was fitted and there was one set of horizontal diving rudders to control the depth of the submarine. When on the surface there was little freeboard and even in a small sea there was the threat of foundering if the hatches were not kept shut. The problem of surface navigation was not helped by the small deck casing and the almost complete absence of what was later to be called a conning tower. The diving time was a matter of a few minutes depending on the amount of reserve buoyancy in the submarine when running on the surface – they were rarely kept in diving trim.

Earlier submarines like those in the French Navy had no periscope for submerged navigation and had to porpoise to the surface for the Commanding Officer to see through glass ports fitted to the side of the hull or in a cupola over the hatch. Even the Hollands when laid down had no such provision, and it was due to the work of Captain Bacon that they went to sea with an “optical tube”. It was called a Unifocal Ball Joint type and stowed horizontally along the hull, being raised about a ball joint by hand. Once raised it could be trained, again by hand. For the user it had the disadvantage that, whilst objects seen ahead were seen in their normal posture, those astern were inverted, while those on the beam were on their sides! Primitive though this may sound, it was an advantage over no periscope at all and it is said that some officers claimed that they thereby gained an instant impression of the relative bearing of the object in view merely from its angle to the vertical. This arrangement did not last long.

Successive Inspecting Captains of Submarines ensured that the Admiralty kept up a steady programme of building and development with provision for new construction being included in the yearly Naval Estimates. After the Hollands, thirteen of the A class were built, followed in turn by the B and C classes, each progressively larger than the other. With the advent of the C class the surface displacement had risen from the Hollands’ 104 tons to 290 tons, and the length from about 100 feet to 135 feet. Even so these boats were still essentially for defensive operations round the coast of the British Isles.

The first big change came in 1906 with the ordering of the first of the D class. In the D1 the surface displacement was nearly double that of the earlier C class, but, more important, she was fitted with two diesel engines driving twin propellers. This was the first of what came to be known as “Overseas” submarines, capable of operating off an enemy shore. In this class the main ballast tanks were no longer fitted internal to the pressure hull but had become saddle tanks running along the outside of the hull, the space thus gained being available to increase the fuel capacity and to improve the habitability. Even so, any improvement in the habitability was marginal, for the crew had increased to a total of twenty-six and additional equipment also competed for any space available. There was no comfort, even sleeping space having to be found by the sailors where they could, and this in a boat intended for offshore work.

The Germans were even later than the British in adopting the submarine as a weapon of war. Admiral von Tirpitz, like so many of his British contemporaries, was firmly against the building of submarines and considered that his prime duty lay in building a big-ship navy to match that of Great Britain. The first submarines built in Germany were sold to the Russians and although the U1 was ordered for the German Navy in December 1904, von Tirpitz had only weakened under strong pressure and remained unconvinced of their value.

Much of the drive necessary to ensure a regular new construction programme of submarines came from Admiral Sir John (“Jackie”) Fisher who was the First Sea Lord until he retired in 1910. Jackie Fisher is more usually remembered for the introduction of the Dreadnought, the battleship which revolutionized the surface battle fleets of the world’s navies, but he also ensured that the Royal Navy did not lag behind in submarine construction. His successor was Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson, perhaps better known for his bravery on land during the campaign against the Dervishes in the Sudan where he won the Victoria Cross. As early as 1901, when Controller of the Navy and so responsible for warship construction, he had called the submarine “a damned un-English weapon” and suggested that in wartime the crews of all submarines captured should be treated as pirates and hanged. It was the performance of the new D1 that now so impressed the new First Sea Lord. During Fleet manoeuvres the submarine had proceeded unaccompanied from Portsmouth to the west coast of Scotland and then “sunk” two cruisers of the “enemy” fleet. As a result Sir Arthur felt that the development of the submarine must be in the hands of an officer who would ensure that this offensive spirit was continued. He appointed Roger Keyes as the next Inspecting Captain of Submarines.

Keyes was no subma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents