- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This cultural history of eighteenth century England explores the world of sex workers, royal scandals, and all manner of immoral behavior.

In Bed with the Georgians reveals the intimate life of Georgian England, where Madams and pimps thrived like never before. It looks at high-class seraglios as well as the brothels, jelly-houses and bagnios which flourished openly, especially in the area around Covent Garden. It looks at courtesans from the highest echelons of society to kept women and common street walkers.

Author Mike Rendell explores how the sex scene was portrayed in contemporary letters and press reports, the role of Grub Street, and the growth of demi-monde celebrity status, with courtesans who flaunted their enormous wealth. In particular, he looks at the way caricaturists satirized the peccadillos of the rich and famous, informing the general public of what their 'social superiors' were up to.

Lavishly illustrated, this volume also contains a glossary covering many aspects of the sex trade in Georgian London.

In Bed with the Georgians reveals the intimate life of Georgian England, where Madams and pimps thrived like never before. It looks at high-class seraglios as well as the brothels, jelly-houses and bagnios which flourished openly, especially in the area around Covent Garden. It looks at courtesans from the highest echelons of society to kept women and common street walkers.

Author Mike Rendell explores how the sex scene was portrayed in contemporary letters and press reports, the role of Grub Street, and the growth of demi-monde celebrity status, with courtesans who flaunted their enormous wealth. In particular, he looks at the way caricaturists satirized the peccadillos of the rich and famous, informing the general public of what their 'social superiors' were up to.

Lavishly illustrated, this volume also contains a glossary covering many aspects of the sex trade in Georgian London.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

The Sex Workers

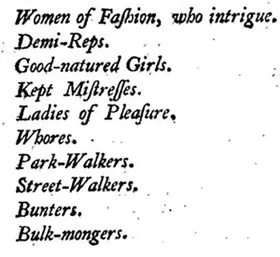

In 1758 a book was published by G. Burnet (author unknown) with the long-winded title of A Congratulatory Epistle from a Reformed Rake to John F…g Esq upon the new scheme of reforming prostitutes. It contained ten gradations of prostitutes, starting with the most genteel, and working down through to the most miserable of sluts:

Looking at each category in turn:

1. Women of Fashion, who intrigue. This classification covered bored wives, perhaps married into the aristocracy, who felt sufficiently liberated to have multiple affairs simply because they wanted love, and sex, and could not find it within marriage. As they did not ‘sell’ sex they cannot really be classed as prostitutes.

2. Demi-reps. Girls of a dubious reputation were called demi-reps, short for demireputation. They would not have ‘lived in’ at the brothel or seraglio, but would have been brought in when customers required their services.

3. Good-natured girls. These were the unmarried women who would have sex with their admirers in return for a good meal and an evening’s entertainment.

4. Kept mistresses. An example would be a courtesan paid an annuity, or provided with a house, by a man who was not her husband, and who would be available for sexual favours although not necessarily on an exclusive basis. In France these kept women were known as ‘dames entretenues’, and the practice of keeping a mistress was termed ‘la galanterie’. In England, a whole new language developed in line with the French – men were no longer adulterers, they were ‘gallants’ and ‘affairs’ became ‘intrigues’.

5. Ladies of Pleasure. These would be attractive, well-spoken prostitutes able to discuss current affairs with their admirers, perhaps play a musical instrument, and who would live in lodgings or high class brothels.

6. Whores. Living in down-market brothels, operating from bagnios, or making a living by picking up custom in the taverns and theatres such as the ones around Covent Garden.

7. Park-walkers. These would attract custom by walking through parks such as Ranelagh and New Spring Gardens (later Vauxhall Gardens). Well-dressed, they would attract male attention by a touch on the elbow or a provocative tilt of a fan.

8. Street-walkers. Openly accosting men in the street, and either servicing their clients in public places, (when they might be termed ‘threepenny stand-ups’) or in garrets or rooms above taverns.

9. Bunters. These were the diseased whores, the lowest of the low. Unclean, often physically scarred by mercury poison and open syphilitic sores, bunters would be found near the docks, willing to exchange their favours for the price of a drink.

10. Bulk mongers. Homeless beggars, living rough and often in the final stages of disease.

The same book goes on to urge readers to accept that the higher class sex-workers were just as likely to corrupt the morals of the nation as the lowly street-walker:

If low, mean, Whores are a Bane to Society, by debauching the Morals, as well as Bodies, of Apprentices, and Lads scarce come to the Age of Puberty; if they frequently infect them with venereal Complaints, which almost as often terminate in as fatal Consequences; if they sometimes urge these youths to unwarrantable Practices for supporting their Extravagance in Gin; do not those in a more dazzling Situation produce still worse Consequences, by as much as they are above the others? Are not youths of good Family and Fortune seduced by these shining Harlots, who more frequently than their Inferiors in Rank, propagate the Species of an inveterate Clap, or a Sound-pox?

Later, the blame is put fairly and squarely on women for corrupting men, rather than the other way round:

There is a Lust in Woman that operates more strongly than all her libidinous Passions; to gratify which she sticks at nothing. Fame, Health, Content, are easily sacrificed to it. Fanny M…y and Lucy C….r have made more Whores than all the Rakes in England. A kept mistress that rides in her Chariot, debauches every vain Girl she meets – such is the Presumption of the Spectator, she imagines the same Means will procure her the same Grandeur. A miserable street walker who perhaps has not Rags enough to cover her Nakedness, more enforces Chastity – I had almost said Virtue – than all the moral Discourses, and even Sermons that ever were wrote or preached.

Put simply, the writer felt that society had less to worry about with the girl in The Whore’s last shift shown as Image 9 than with the high-class prostitute in her finery, such as in Image 1 entitled A Bagnigge Wells Scene, or no resisting Temptation. The latter print was published by Carington Bowles in 1776 and shows two well-dressed prostitutes plying their trade at the popular watering hole. They are dressed in the latest fashions, they are smart and respectable – something a young girl might aspire to look like. In The Whore’s last shift published just three years later, the title is a pun on the word ‘shift’ – the whore has had her last customer of the day, and is washing her flimsy garment, i.e. shift, in a cracked chamber pot. No-one would call it an aspirational image.

Caricaturists loved to parody the extremes, such as with the contrasting images of ‘the great impures’ of St James’s and of St Giles shown as Image 6. It was created by Thomas Rowlandson in 1794, and demonstrates the differences between the glamorous courtesans of St James and the rough and ready good-time girls from St Giles. Either way, the ‘happy hooker’ image, the ‘tart with a heart’ having a good time, was well and truly established by the eighteenth century. However, both the high-class woman and the street worker were seen as having one thing in common – they operated for money. Dividing the Spoil shown as Image 7 shows that whereas the St James’s ladies ripped off punters at the game of Faro by operating a crooked deck of cards, and then shared out the ill-gotten gains, they were no better than the whores down the road in St Giles’s, who shared out the proceeds of picking pockets and stealing watches from their foolish customers.

Certainly if you were a household drudge, rising at five to sweep out and re-lay the fires, spending all day on your hands and knees, you must have thought ‘I’m in the wrong job’ if you saw a courtesan drive by in her phaeton drawn by four matching greys, especially once you realised that it would take you several years to earn what ‘Fanny M…y’ or ‘Lucy C…r’ could make in a couple of days simply by lying on her back thinking of England. Imagine someone in one of the needle trades, such as the humble milliner, working on a splendid head-dress made of fine silks and plumed with ostrich feathers, expecting the creation to be collected by a duchess or countess, and then discovering that it was to be worn by someone who was themselves once a milliner. William Hogarth was one of many who suggested that the ranks of prostitutes were mostly made up of recruits from the Provinces, who would come up to London and there fall prey to wily brothel keepers. Thus Hogarth’s first plate in the six-part series called The Harlot’s Progress (see Image 8) shows the notorious procuress Mother Needham ensnaring the young fresh-faced girl called Moll Hackabout. However, the temptation to ‘have a go’ was all too easy and, in practice, many entered the profession knowingly and willingly.

It is interesting to remember that admission to what became known as the ‘Cyprian Corps’ allowed for both upward and downward movement – more usually the latter, as sickness took its inevitable toll. At the start of her career, an attractive girl could aim for the stars. Her value, as a virgin, was perhaps fifty times the amount she would command as ‘used goods’ but a clever bawd would show the girl how to ‘restore her virginity’ many times over. It was commonplace to insert a small piece of bloodied meat, or a sponge soaked with blood, inside the vagina so that a lover would mistake the signs of bleeding for the breaking of the long-ago ruptured hymen. The author Nicholas de Venette, in his 1712 book The Mysteries of Conjugal Love Reveal’d gave advice to brides who were no longer chaste and who wished to deceive their husband, to the effect that they should insert lambs blood into the vagina on their wedding night. For the more adventurous, surgeons were already performing operations to ‘tidy up’ the labia by means of a labiaplasty. Simpler, non-surgical, procedures involved the application of water impregnated with alum, or other astringents.

At the outset, a young girl might hope to catch the eye of an aristocratic gentleman. It is interesting in this context to see the images in the caricature by Richard Newton entitled Progress of a Woman of Pleasure. It appears as Image 4 and 5.

The first picture shows the girl in country garb arriving in town, where she has been placed in ‘the house of a Great Lady in King’s Place’. King’s Place was the home of the legendary bawd Charlotte Hayes, who is featured in Chapter Three. Scene two shows the lady in question at the start of her career, under the caption ‘I see you now waiting in full dress for an introduction to a fine Gentleman with a world of money’. The third scene shows her ‘in high keeping’ accompanying her Adonis to the Masquerades. But our heroine has a character flaw – she cannot hold her drink and she loses her temper too readily.

The fourth image shows her flinging a glass in the face of her keeper. She is turned out and her only consolation is that her hairdresser has promised to marry her, but he offers her an annuity of only £200 a year. Furious, she complains that for that money she could get the smartest Linen Drapers Man in London, and chucks him out as being a dirty rascal.

By now she is forced to move to Marylebone, where she exhibits herself in the Promenade in Oxford Street – in other words she has slipped down the list from kept woman to street walker. The downward spiral continues – she scorns a customer who offers her a crown (five shillings), insisting that she wants five guineas (more than twenty times the amount offered). She starts knocking back the brandy to hide her disappointment with life, earning a few shillings dancing at a sleazy emporium in Queen Anne Street East. She gets involved in a brawl, earning herself a warrant and two black eyes.

Before long, she is selling her favours to an apprentice boy who has stolen half a crown from his master’s till. She moves into a sponging house (i.e. she is confined there on account of her debts) pawns a silver thimble to pay for breakfast, and becomes a servant of a woman who was formerly her servant, only able to afford a bunch of radishes and a pint of porter for her dinner. She is drunk on cheap gin. The journey into oblivion ends up with her slumped on the doorstep of the house of ‘this female monster’ who has turned her out into the street in case she gets lumbered with the expense of a funeral.

The whole progress is far more ‘fun’ that Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress – it doesn’t moralise or suggest that whoring was inherently immoral, merely that failing to hold your liquor and assaulting your customers is bad for business. The non-censorious viewpoint is perhaps not surprising given that the brilliant Richard Newton was aged 19 when he drew it – he died of ‘gaol fever’ two years later in 1798, and his caricatures suggest that he was well acquainted with the seedier side of life and probably knew many prostitutes personally. The images are delightfully drawn caricatures, far removed from the serious tone of the meticulously staged Hogarth scenes in ‘The Harlot’s Progress’. The modern equivalent would be the busty cartoon figure of Jessica in ‘Who framed Roger Rabbit’.

What then was the attitude of the second oldest profession (i.e. the Law) to its senior profession? Prostitution was never illegal under Common Law and prosecutions could only be brought if the offence was linked with disorderly conduct, public indecency, or some other crime. ‘Keeping a bawdy-house’ was an indictable misdemeanour at Common Law but there were often difficulties in proving the identity of the proprietor of the premises, and the sort of evidence needed to prove the offence was generally only available from someone who had actually attended the premises, that is to say as a paying customer. Bawds simply had to factor in the cost of employing lawyers to defend them against prosecution in the charges they passed on to their customers.

Periodically, reform societies pushed for prosecutions to be brought. The records of the ‘Societies for Promoting a Reformation of Manners’, in their thirtieth account of the Progress made in the Cities of London and Westminster, stated:

the said Societies have in pursuance of their said design from 1 December 1723 to 1 December 1724 prosecuted divers sorts of offenders viz:

Lewd and Disorderly Persons 1951

Keeping of Bawdy and Disorderly houses 29

They also claimed to have prosecuted 600 people for breaking the Sabbath, 108 for swearing and cursing, and twelve for drunkenness, adding: ‘The total prosecuted in and near London for debauchery and profaneness for the thirty three years past was 89,333’. Various Vagrancy Acts had been passed, particularly in 1609 and 1744, but these did not make prostitution an offence. In 1752 Parliament passed an Act against the keeping of Disorderly Houses, but this did not in itself criminalise sexual solicitation e.g. by street walkers. The Act was primarily aimed at the public nuisance caused when premises were used for the illegal sale of alcohol, or as gambling dens, or for unlicensed dancing and rowdy entertainment. Unusually, the 1752 Act made it a legal requirement that publicly funded prosecutions were to be brought if two or more parishioners were prepared to act as informants. Previously, any such prosecutions would have had to have been privately funded. However, few parishioners would volunteer to give evidence that they had entered a brothel, let alone be tarred with the name of ‘informer’. The brothel owner was, after all, a neighbour and generally bawds employed ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Sex Workers

- Chapter 2 The Alphabet of Sex, and More Besides

- Chapter 3 Of Brothels and Bagnios, Madams and Molls

- Chapter 4 Courtesans and Harlots

- Chapter 5 Sex and Satire in Print

- Chapter 6 Royal Scandals and Shenanigans

- Chapter 7 Adulterous Aristocrats

- Chapter 8 Sex Crimes – Rape, Bigamy, Murder, Suicide and Sodomy

- Chapter 9 Rakes, Roués and Romantics

- Glossary: A Selection of Sexual Terms

- Bibliography

- Plate section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access In Bed with the Georgians by Mike Rendell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.