![]()

1

… one great and striking success … will have far-reaching results.

The Flanders Plan

Captain Oliver Woodward of the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company spent the night before the Battle of Messines with ‘nerves stretched to the breaking point’, checking and re-checking the cables and circuits connecting the mines at Hill 60 to the firing switches.1 Similar preparations were under way across the battle front at the 18 other workings in what was the First World War’s most ambitious and remarkable feat of engineering. Woodward was one of the few below the very senior levels of command aware of both the existence of the mines and the timing of the attack. Beneath Hill 60, and the nearby high point known as the Caterpillar, among the most hotly contested positions on the Western Front, the 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company had placed 55,000 kilograms of high explosive in two giant mines. The Australians, having taken over from the Canadians in November of 1916, were responsible for ensuring that all the work and sacrifice invested in constructing and defending the mines would not be in vain. Woodward was right to be nervous. The mines, along with their detonators and the network of electrical cables to fire them, had been in place 30 metres below the damp Flanders clay for almost a year.2 The thought that some minor fault in the equipment, a break in a cable, or circuit failure would, at the eleventh hour, undo all the effort that had been invested, drove his relentless cycle of checks. ‘I approached the final testing’ wrote Woodward, ‘with a feeling of intense excitement.’3

For two years an unseen but immensely important battle had been fought underground at Messines as the British undermined the ridge and the Germans counter-mined to block them.4 It was a battle very few knew about and fewer still could face. By June 1917 the ground under Hill 60 was honeycombed with tunnels dug by both sides, the Germans searching for the galleries which led to the mines and the Australians digging to divert, deceive and block them. The suffocating darkness of the deep tunnels was the province of the brave. ‘Generally men are not afraid of death, but only of the manner of dying’ wrote Bernard Newman, companion writer to Captain Walter Grieve in his 1936 book on the tunnellers of the First World War. ‘No one envied the Tunneller his comparative security from enemy bombardment, deep in his burrow, usually far out in front of our front line. Everyone could easily visualise the special terrors which awaited him at every second of his duty – the collapse of a gallery, due to the wrath of Nature or enemy, and the subsequent waiting for death in its most horrible form, gasping for air until death came as a relief.’5

The tunnellers of Messines, most of them miners in civilian life, were fully aware of the dangers they faced, but those ‘special terrors’ did little to slow the incessant digging. Messines and Wytschaete today sit above an underground network of shafts, dugouts and tunnels so extensive that the ground above is still unstable in places. At the widest point of no man’s land, the tunnel entrances were over 600 metres from their mine chambers and, because the miners needed to penetrate the deep layer of water-bearing ‘Kemmel’ sands, a soggy glutinous soil which could not support tunnels, they were up to 40 metres deep. The deep vertical shafts through the Kemmel sands were created by ‘tubbing’, successively adding cylindrical segments of steel which bolted together creating a solid and watertight vertical shaft down to the layer of blue clay which was ideal for tunnelling. At Hill 60, the vertical shaft was 28 metres deep before it hit the clay layer and the two branches were eventually driven under the German lines. ‘Clay-kickers’, lying on wooden supports, used their feet to drive spades into the clay, the spoil bagged by an assistant and wheeled out along rails on small trolleys. The distinctive blue clay from the lower strata was then carefully hidden from airborne German cameras to disguise the fact that the British had driven shafts so deep below the surface. The tunnel was progressively boarded as the kickers drove forward at an impressive rate of up to eight metres a day. Although men could stand upright in the entrance galleries and ante-chambers, the narrow tunnels which ran for hundreds of metres to the working face were just over a metre high by half a metre wide. The claustrophobic narrowness was important for economy, but also because the tunnel had to be ‘tamped’ (sealed) for much of its length to concentrate the explosive force upward instead of back along the tunnel. With the two giant mines at Hill 60 and the Caterpillar placed and tamped in July and October 1916, the Australians defended them by creating ‘dummy’ tunnels, drawing the German miners away from the actual mine chambers by digging shallower works. Such back-breaking labour in the narrow, deep confines with the danger of death by carbon monoxide poisoning, a sudden crushing enemy explosion, slow suffocation or being trapped by a tunnel collapse required a nerve few possessed.

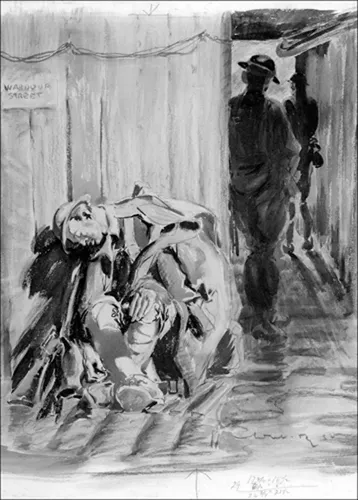

Dead beat, the tunnel, Hill 60, Will Dyson’s drawing of an exhausted Australian soldier sleeping in the tunnel at Hill 60. The sketch poignantly captures the impact of the difficult and dangerous work of the tunnellers. Dyson set out to show the true impact of the fighting, at one point noting, ‘I never drew a single line except to show war as the filthy business that it was.’ (AWM ART 02210).

After two and a half years of digging, the British had successfully placed 25 mines under the ridge and zero hour was fixed for 3.10 am on 7 June.6 Most of the works had been silent for months. The lack of activity led the Germans to the mistaken conclusion that the British had abandoned most of their tunnels, and active counter-mining threatened few of the established mines. At Hill 60 however, fierce mining and counter-mining continued until the eve of detonation. Several times the Germans came close to breaking into the main galleries and, as the final hours approached, the galleries at Hill 60 were still guarded by listeners. As they maintained their lonely vigils on the night of 6 June, the men of IX, X and II Anzac Corps left their barracks and staging areas to begin their long, circuitous and intricately planned marches to arrive ready for the launch of the attack. Crawling towards the front lines in the dark at six kilometres per hour were 72 tanks which would support the infantry attack. Since coordination with the infantry was vital for the attack, the timetables and routes for the tanks were also carefully prepared to position them just in time for the assault. In the skies above the ridge, scores of British aircraft circled, occasionally diving to strafe the German trenches and masking the noise of the tanks. Nothing on this scale and with such grand ambition had been attempted by the British so far. At a press conference that night Harington would famously quip, ‘Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography.’7 By 2.00 am most of the nine divisions of assault troops were in their assembly trenches and the gunners stood silent and ready beside the huge dumps of shells waiting for the orders to unleash the heaviest bombardment of the war. In his memoirs, Oliver Woodward described the agonising anxiety of waiting as Brigadier John Lambert of the British 23rd Division, whose men were to capture Hill 60, stood beside him in the firing dugout, watch in hand, ready to count down the minutes to firing. As Lambert began the countdown from 10 seconds, Woodward grasped the handle of the firing switch.8

• • •

The chain of events that laid Woodward’s hand at the ready can be traced back to 1914 and the bloody deadlock which descended on the Western Front when the invading German divisions slowed and stalled in Flanders. Fighting around the medieval market city of Ypres began in October 1914 when the British commander, General Sir John French, fell back on the city, determined to hold his line with the small British Expeditionary Force of seven divisions. For centuries the Flemish who farmed the land around Ypres have known it as Heuvelland (Ridgeland) for the modest heights that gently undulate across the otherwise pancake-flat farmlands of Flanders. The low ridges radiating out from Ypres formed natural defensive lines and, with the French under General Ferdinand Foch defending the southern flank, the defenders of Ypres held back German attacks throughout October. The opposing lines began to take the shape which would become so familiar to the British defenders over the next three years, bulging out around Ypres with the city at the centre of a dangerous salient, an intrusion into the enemy lines. The southern quadrant of the salient was dominated by the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge which rises to just over 65 metres above the surrounding countryside commanding a view which sweeps to the far horizon.9 Woodward wrote that:

On leaving Ypres by the Lille Gate there is seen about two miles distant a low range of hills, the highest point of which is slightly over 100 feet above the level of the city. This ridge forms the northern section of what is known as ‘The Messines Ridge’. Virtually due east of Lille Gate, the Ypres-Menin railway runs through this ridge just to the north of the cutting here is the highest point ‘Hill 60’.10

On 31 October, German cavalry captured Messines and the heights to the south of Ypres and, two weeks later, French’s battered divisions held back an offensive aimed at capturing Hooge, just four kilometres to the north of the city. The fighting continued until 22 November when winter closed down the battle. The wreckage of the Schlieffen Plan had left the Germans in command of the ridges ringing the Ypres salient and both sides planning offensives for the spring. South of the city, the Germans began to dig in on their high tide mark on the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge. The villages on the crest of the ridge were slowly pulverised by regular shelling, the houses and public buildings systematically destroyed. Driven below the surface, the Germans began to fortify the villages. Cellars were strengthened and converted to dugouts, farms were turned to concrete fortresses and everywhere the crenelated trench lines meandered across the contours of the ridge. Linked by communication and supply trenches, they formed what became effectively a subterranean street network. The Church of St Nicolas in Messines, with its foundation stone laid in 1057 by Countess Adela of France, mother of an English queen, was gradually reduced to rubble. Her crypt now served as a German first aid and command post.11 Messines’ grandest and largest building was the Institute Royale de Messines, a school and orphanage for the daughters of Belgium’s war dead. In one of the Great War’s many cruel ironies, the orphans of Messines were put to flight by the invaders of 1914 and the Institute Royale, along with the sanctuary and comfort it offered to some of the most defenceless victims of war, was eventually obliterated by the fighting.

The Ypres salient would acquire an odious reputation in the First World War. The crescent of German lines around Ypres allowed the German artillery to target the British positions from three sides and nowhere within the salient was safe. For the Germans, their occupation of the Messines Ridge also produced a salient, although they held the high ground and, unlike the British, were not so easily observed and targeted. However, such broad intrusions into the enemy’s territory were obvious targets for attack at the curves’ extremities which could ‘pinch off’ the salient, surrounding and trapping an enemy in the line’s forward positions. Even to an untrained eye glancing at a map of the ridge, the key points for any British attack on the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge are so obviously the positions between Hill 60 in the north and St Yves in the south that no-one on either side was unaware of their importance. Thanks to the deadly equilibrium of the salient, and the spoil from the railway cutting that raised it slightly above the surrounding heights, the unimpressive Hill 60 became one of the most important positions on the Western Front and, by 1917, it had changed hands several times since the outbreak of war.

Plumer’s plan to attack the ridge and wipe out the threat to his southern flank was patiently developed over 1915 and 1916. While the British intention to capture the ridge was certainly no secret, the hugely ambitious mining program which began in 1915 certainly was. Although the mining at Hill 60 and other highly prized positions was a constant threat, at no stage did the Germans fully appreciate the massive scale of the mining effort nor the very real threat that it posed to their positions. Nevertheless, an attack on the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge in 1916, although it would have been an important tactical victory and removed a major threat to the Ypres salient, would still have been only of local importance. By May of 1917 however, a shift in the Allied grand strategy would bring an entirely different and far more significant purpose to the capture of Messines Ridge as the first important step towards a war-winning offensive.

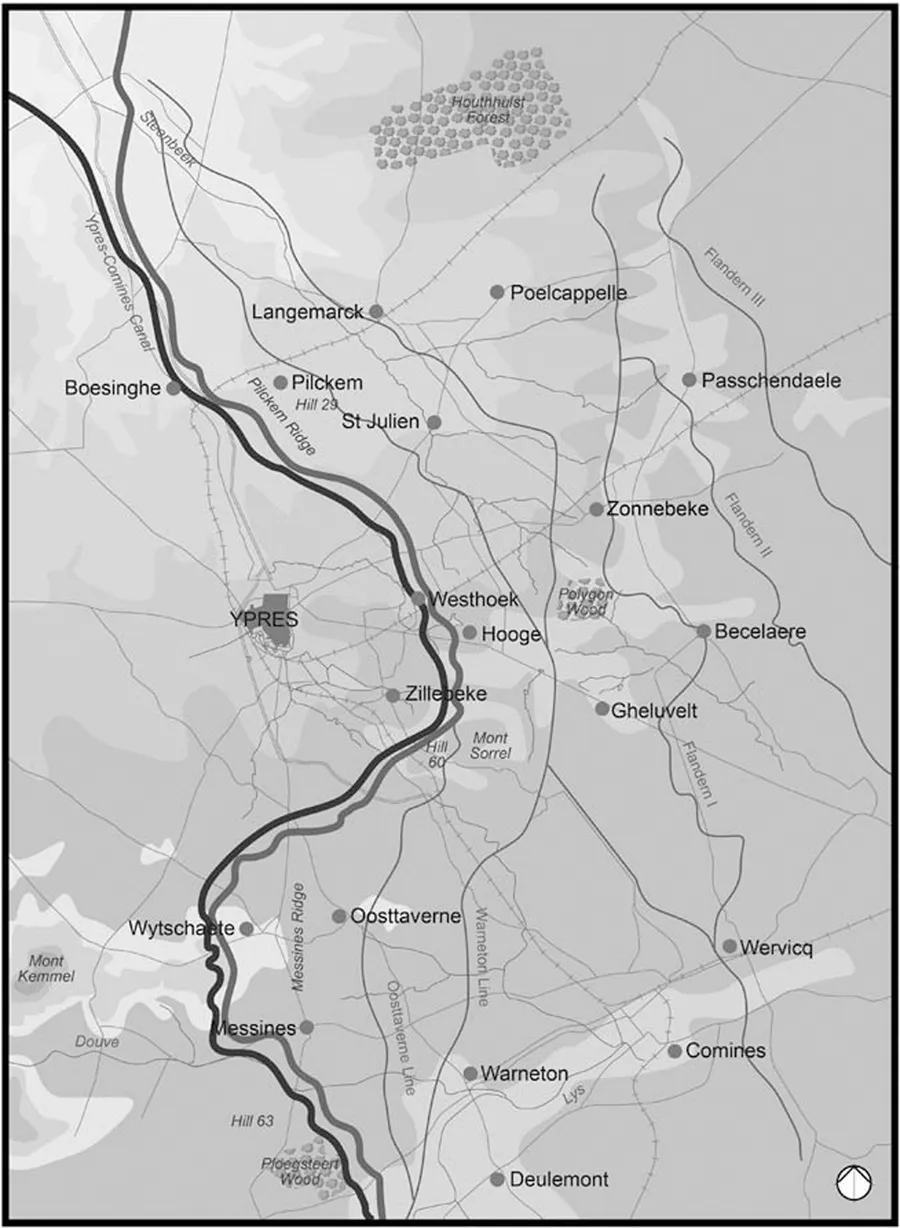

Map 2. The Ypres salient. The German offensive of 1914 stalled in Flanders and their armies occupied the ridge tops ringing the Belgian city of Ypres. The resulting salient with Ypres at the centre could be fired on from three directions and was a costly and dangerous position for the British to hold.

• • •

As the winter of 1916–17 closed in, fighting on the Western Front wound down. Major offensive operations were impossible during winter and this one would prove exceptionally severe. The opposing armies were occupied with the mundane but crucial business of preparing their winter quarters, strengthening defences and supply. All the while, shelling, sniping and raiding as well as illness produced the ‘wastage’ that so concerned the commanders of both sides. The winter itself took men from the firing line through trench foot, hypothermia and influenza, and an army confined to trenches in the winter of northern Europe, as both sides knew, was an army slowly yet surely wasting away. With the stalemate on the Western Front showing no signs of breaking, the Allies met at Chantilly in November of 1916 to plan for the coming campaigning season. They quickly agreed on a strategy of exerting maximum pressure on the Central Powers through coordinated offensives which would involve major attacks by the French and British north and south of the Somme, coordinated with offensives by the Russians, Italians and the minor powers on their own fronts. Such cascading hammer blows would, it was believed, rob the Central Powers of any opportunity to shift reserves to counter each individually. The advantages of an offensive strategy lay also in seizing the initiative, keeping the enemy off balance and forestalling any assault on their own lines. It was also a strategy which played to the Allies’ strength, for 1917 was judged to be the year in which the power balance in guns and men would be at its optimum in their favour. The awful casualties of Verdun and the Somme were weighed against what were believed to be even greater German losses and the mathematics of attrition promised to forc...