- 652 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Earl Ziemke's

From Stalingrad to Berlin is a definitive, illustrated history of the Soviet-German conflict during World War II.

Introduction by Emmy Award–winning historian Bob Carruthers

With scarcely an interlude, Germany clashed with the Soviet Union for 3 years, 10 months, and 16 days, seesawing across eastern and central Europe between the Elbe and the Volga, the Alps, and the Caucasus. The total number of troops continuously engaged averaged between 8 and 9 million, and the losses were appalling. Wehrmacht losses numbered between 3 and 3.5 million. Deaths on the Soviet side reached more than 12 million, about 47 percent of the grand total of soldiers of all nations killed in World War II. The war and the occupation cost the Soviet Union some 7 million civilians and Germany about 1.5 million. The losses, civilian and military, of Finland, the Baltic States, and eastern and southeastern European countries added millions more.

The great struggle completely unhinged the traditional European balance of power. The war consolidated the Soviet regime in Russia, and enabled it to impose the Communist system on its neighbors, Finland excepted, and on the Soviet occupation zone in Germany. The victory made the Soviet Union the second-ranking world power.

From Stalingrad to Berlin presents the strategy and tactics, partisan and psychological warfare, coalition warfare, and manpower and production problems faced by both countries, but by the Germans in particular, to create this authoritative account of the battles between these European nations.

Introduction by Emmy Award–winning historian Bob Carruthers

With scarcely an interlude, Germany clashed with the Soviet Union for 3 years, 10 months, and 16 days, seesawing across eastern and central Europe between the Elbe and the Volga, the Alps, and the Caucasus. The total number of troops continuously engaged averaged between 8 and 9 million, and the losses were appalling. Wehrmacht losses numbered between 3 and 3.5 million. Deaths on the Soviet side reached more than 12 million, about 47 percent of the grand total of soldiers of all nations killed in World War II. The war and the occupation cost the Soviet Union some 7 million civilians and Germany about 1.5 million. The losses, civilian and military, of Finland, the Baltic States, and eastern and southeastern European countries added millions more.

The great struggle completely unhinged the traditional European balance of power. The war consolidated the Soviet regime in Russia, and enabled it to impose the Communist system on its neighbors, Finland excepted, and on the Soviet occupation zone in Germany. The victory made the Soviet Union the second-ranking world power.

From Stalingrad to Berlin presents the strategy and tactics, partisan and psychological warfare, coalition warfare, and manpower and production problems faced by both countries, but by the Germans in particular, to create this authoritative account of the battles between these European nations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Stalingrad to Berlin by Earl Zeimke in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781473847866Subtopic

Russian HistoryCHAPTER I

Invasion!

As the war passed into its fourth year in early September 1942, Adolf Hitler, the German Fuehrer, Commander in Chief of the German Armed Forces and Commander in Chief of the German Army, was totally absorbed in his second summer campaign against the Soviet Union. 1For the last month and a half he had directed operations on the southern flank of the German Eastern Front from a Fuehrer headquarters, the WERWOLF, set up in a small forest half a dozen miles northeast of Vinnitsa in the Ukraine. With him, in the closely guarded headquarters community he rarely left, one of pleasantly laid out prefabs and concrete structures, he had his personal staff, through which he exercised the political executive authority in Germany and the occupied territories; the chief of the Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW)), Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel; and a field detachment of the Armed Forces Operations Staff (Wehrmachtfuehrungsstab (WFSt)) under its chief, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl. In Vinnitsa, a hot, dusty provincial town, the Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH)), had established its headquarters under the Chief of Staff, OKH, Generaloberst Franz Halder. Through it Hitler commanded the army groups and armies in the Soviet Union.

During the summer German Army groups A and B had made spectacular advances to the Volga at Stalingrad and into the western Caucasus. In August mountain troops had planted the German flag at the top of Mount Elbrus, the highest peak in the Caucasus. But before the month ended, the offensive had begun to show signs of becoming engulfed in the vast, arid expanses of southern USSR without attaining any of its strategic objectives; namely, the final Soviet defeat, the capture of the Caucasus and Caspian oil fields, and the opening of a route of debouchment across the Caucasus into the Middle East. Hitler had become peevish and depressed. At the situation conferences his specific objections to how the offensive was being conducted almost invariably led on to angry questioning of the ability of the generals and their understanding of the fundamentals of military operations.

On the afternoon of 9 September, after a particularly vituperative outburst the day before against Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm List, whom he had repeatedly accused over the past weeks of not following orders and of not properly deploying his troops, Hitler sent Keitel to Vinnitsa to tell Halder that List should submit his resignation as Commanding General, Army Group A. Hitler intended to take command of the Army group in person. To Halder, Keitel “hinted” that changes in other high posts were in the offing, including Halder’s own. In fact, Hitler had already decided to dismiss Halder, who, he claimed, was “no longer equal to the psychic demands of his position.” He also considered getting rid of his closest military adviser, Jodl, who had made the mistake of supporting List.

Germany in August 1942 was at the peak of its World War II military expansion. It held Europe from the Pyrenees to the Caucasus, from Crete to the North Cape, and Panzer Army Africa had pushed into Egypt. During the summer’s fighting in southern USSR mistakes—for which Hitler was trying to give the generals all the blame—had been made, but these mistakes alone were not enough to account for the massive frustration that was being felt. It was rooted in a more fundamental miscalculation.

In the directive for the 1942 offensive Hitler had established as the paramount objective, “… the final destruction of the Soviet Union’s remaining human defensive strength.”He had assumed that the Soviet Union would sacrifice its last manpower reserves to defend the oil fields and, losing both, would be brought to its knees. That had not happened. In late August the Eastern Intelligence Branch, OKH, had undertaken to assess the Soviet situation as it would exist at the close of the German offensive. It had concluded that the Soviet objectives were to limit the loss of territory as much as possible during the summer, at the same time preserving enough manpower and matériel to stage a second winter offensive. It had assumed that the Soviet command had resigned itself before the start of the German offensive to losing the North Caucasus and Stalingrad, possibly also Leningrad and Moscow and that consequently the territorial losses sustained, though severe, had not been unexpectedly so. Moreover, the Soviet casualties had fallen considerably below what might have been anticipated on the basis of the German 1941 offensive. In sum, the Eastern Intelligence Branch had judged that the Soviet losses were “on an order leaving combat worthy forces available for the future” and that the German losses were “not insignificant.”

A Russian Highway.

THE GERMAN COMMAND

On 24 September 1942 General der Infanterie Kurt Zeitzler replaced Halder as Chief of Staff, OKH. In his farewell remarks to Halder, delivered in private after that day’s situation conference, Hitler said that Halder’s nerves were worn out and that his own were no longer fresh; therefore, they ought to part. He added that it was now necessary to educate the General Staff in “fanatical faith in the Idea” and that he was determined to enforce his will “also” on the Army, implying thereby—and by his lights no doubt with some justification—that under Halder’s stewardship the Army had clung too stubbornly to the shreds of its independence from politics and to its traditional command principles.

Zeitzler’s appointment surprised everyone, including himself. He was a competent, but not supremely outstanding, staff officer. As Chief of Staff, Army Group D, defending the Low Countries and the Channel coast, his energy and his rotund figure had earned him the nickname “General Fireball.” In one of the long evening monologues that have been recorded as table talk, Hitler, in June 1942, had remarked that Holland would be a “tough nut” for the enemy because Zeitzler “buzzes back and forth there like a hornet and so prevents the troops from falling asleep from lack of contact with the enemy.” Apparently, Hitler had decided that he preferred a high level of physical activity in the Chief of Staff to the, as he saw it, barren intellectualism of Halder and his like among the generals.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE COMMAND

The dismissal of Halder and Zeitzler’s appointment as Chief of Staff, OKH, marked another stage in an enforced evolution that Hitler had imposed on the German command structure since early 1938. At that time, also to an accompaniment of dismissals in the highest ranks, he had abolished the War Ministry and personally assumed the title and functions of Commander in Chief of the German Armed Forces. To take care of routine affairs and to provide himself with a personal staff as Commander in Chief, he had created the Armed Forces High Command and placed Keitel at its head with the title Chief, OKW. As the country moved toward and into the war, the Armed Forces Operations Staff, one of the sections within the OKW, under its capable chief, Jodl, would assume staff and planning functions paralleling and often competing with those of the service staffs. Seeking a more pliant top leadership in the Army High Command, Hitler had at the same time appointed Generaloberst (later Generalfeldmarschall) Walter von Brauchitsch, Commander in Chief, Army, and Halder, Chief of Staff, OKH. As Chief of Staff, OKH, Halder also headed the most exclusive and influential group within the Army, the Army General Staff.

Very early in the war Hitler had revealed that he was going to take an active part in directing military operations. His formal instrument for exercising control was the Fuehrer directive, which laid down the strategy and set objectives for a given operation or a major part of a continuing operation. At least in the early years, it usually embodied the thinking of the staffs as approved or amended by Hitler. The Fuehrer directives were issued through the Operations Staff, OKW, which gave that organization a voice in all crucial, high-level decisions even though it did not bear direct command responsibility.

The invasion of Norway and Denmark in April 1940 had introduced new planning and command procedures and had set precedents that were to be followed on a larger scale in the future. The Operations Staff, OKW, under Hitler, had then assumed direct planning and operational control, and the service commands had only supplied troops, equipment, and support. That change in the long run affected the Army most because land operations could be more easily parceled out among the commands and because neither Hitler nor Jodl and the Operations Staff, OKW, were competent to handle the technical aspects of air or naval operations and were therefore inclined to leave them to the appropriate service staffs. By the summer of 1941 the OKW commanded—usually through theater commanders—in Norway, the West (France and the Low Countries), the Balkans, and North Africa. The OKH bore command responsibility for the Eastern Front (USSR) only and not for the forces in northern Finland or for liaison with the Finnish Army, both of the latter being included within the OKW’s Northern Theater.

THE PLAN FOR INVASION

By the time the campaign against the Soviet Union came under consideration in the late summer of 1940, Hitler and the German Army had three brilliant victories behind them—Poland, Norway and Denmark, and France. The German Army appeared invincible, and even to the skeptics Hitler had begun to look like an authentic military genius. In that atmosphere there probably was more fundamental unanimity in the upper reaches of the German command than at any other time, either before or later.

The main problems associated with an operation in the Soviet Union appeared to be geographical, and they were obvious, if not necessarily simple, of solution. One such was the climate, which was markedly continental with short, hot summers, long, extremely cold winters, and an astonishing uniformity from north to south, considering the country’s great expanse. The climate, unless the Germans wanted to risk a long, drawn-out war or a winter campaign for which the Wehrmacht was not trained or equipped, imposed on them a requirement for finishing off the Soviet Union in a single summer offensive of not more than five months’ duration. Consequently, in the very earliest planning stage, at the end of July 1940, Hitler had put off the invasion until the following summer. The rasputitsy (literally, traffic stoppages) brought on by the spring thaw and the fall rains, which turned the Soviet roads into impassable quagmires for periods of several weeks, imposed additional limitations on the timing.

The paramount problem was the one which had also confronted earlier invaders, how to accomplish a military victory in the vastness of the Russian space. Apart from the Pripyat Marshes and several of the large rivers, the terrain in European USSR did not offer notable impediments to the movement of modern military forces. But maintaining concentration of forces and supplying armies in the depths of the country presented staggering, potentially even crippling, difficulties. The whole of the Soviet Union had only 51,000 miles of railroads, all broader gauged than those in Germany and eastern Europe. Of a theoretical 850,000 miles of roads, 700,000 were no more than cart tracks; 150,000 miles were allegedly all-weather roads, but only 40,000 miles of those were hard surfaced.

Hitler and the generals agreed that the solution was to trap and destroy the main Soviet forces near the frontier. In December 1940, however, when the strategic plan was being cast into the form of a Fuehrer directive, the generals disagreed with Hitler on how to go from that to the next stage, the final Soviet defeat. Halder and Brauchitsch proposed to concentrate on the advance toward Moscow. In that direction the roads were the best, and they believed the Soviet Union could be forced to commit its last strength to defend the capital, which was also the most important industrial complex and hub of the country’s road and railroad networks. Hitler, however, was not convinced that the war could be decided at Moscow, and he had his way. Fuehrer Directive 21 for Operation BARBAROSSA, the invasion of the Soviet Union, when it was issued on 18 December 1940, provided for simultaneous advances toward Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev and for a possible halt and diversion of forces from the Moscow thrust to aid the advance toward Leningrad. For the moment, the difference of opinion on strategy cast only the slightest shadow on the prevailing mood of optimism. Staff studies showed that the Soviet Union would be defeated in eight weeks, ten weeks at most.

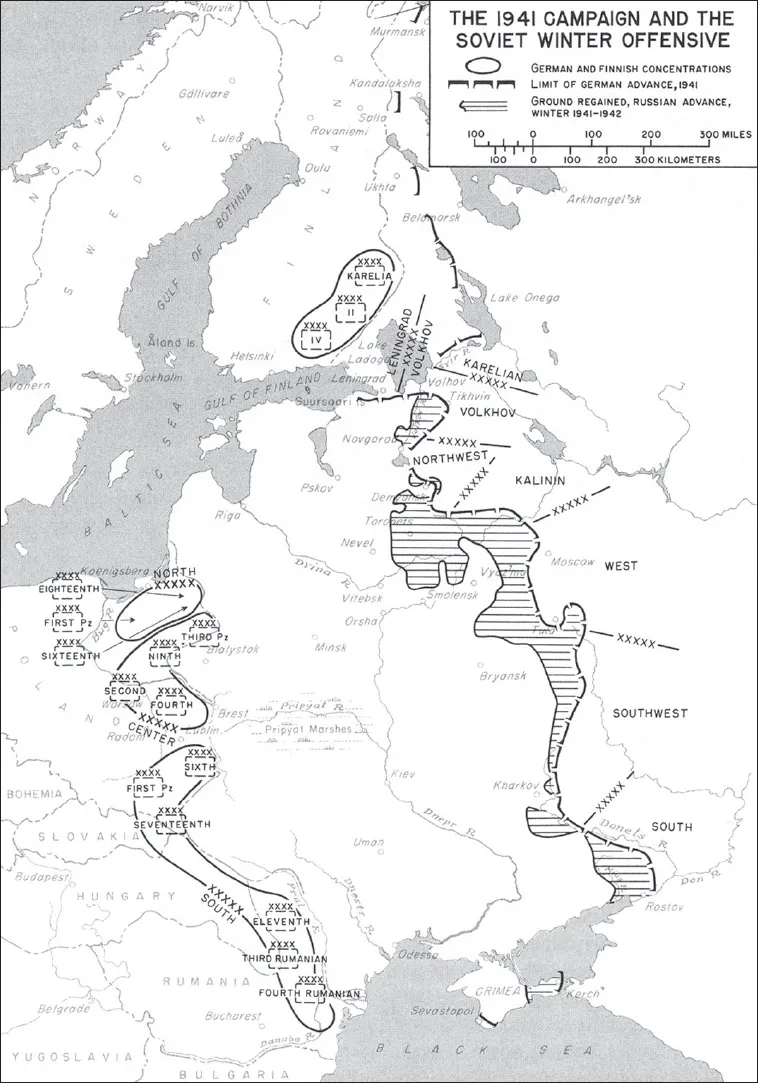

The Army operation order for BARBAROSSA was issued in early February 1941, and the build-up on the eastern frontier began shortly thereafter, gradually at first. (Map 1) The OKH assigned 149 divisions, including 19 panzer (armored) divisions, to the operation. The total strength was 3,050,000 men. Army of Norway was to deploy another 4 divisions, 67,000 troops, in northern Finland. The Finnish Army eventually added another 500,000 men in 14 divisions and 3 brigades, and Rumania furnished 14 infantry divisions and 3 brigades, all of them understrength, about 150,000 men. The BARBAROSSA force initially had 3,350 tanks, 7,184 artillery pieces, 600,000 motor vehicles, and 625,000 horses.2

The most significant assets of the German Army on the eve of the Russian campaign were its skill and experience in conducting mobile warfare. The panzer corps, employed with great success in the French campaign of 1940, had been succeeded by a larger mobile unit, the panzer group. Four of these were to spearhead the advance into the Soviet Union. The panzer groups were in fact powerful armored armies, but until late 1941, conservatism among some senior generals prevented them from getting the status of full-fledged armies.

Map 1: The 1941 Campaign and the Soviet Winter Offensive

Seven conventional armies and four panzer groups were assigned to three army groups, each responsible for operations in one of the main strategic directions. Army Group North, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm von Leeb, was to attack out of East Prussia, through the Baltic States toward Leningrad. Army Group Center, under Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, assembled on the frontier east of Warsaw for a thrust via Minsk and Smolensk toward Moscow. Army Group South, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt commanding, was responsible for the sector between the Pripyat Marshes and the Black Sea and was to attack toward Kiev and the line of the Dnepr River. The Finnish Army, operating independently under its own Commander in Chief, Marshal Carl Mannerheim, was to attack south on both sides of Lake Ladoga to increase the pressure on the Soviet forces defending Leningrad and so facilitate Army Group North’s advance. An Army of Norway force of two German and one Finnish corps, under OKW control, was given the mission of attacking out of northern Finland toward Murmansk and the Murmansk (Kirov) Railroad. The Rumanian forces, Third and Fourth Armies, attached to Army Group South, had the very limited initial mission of assisting in the conquest of Bessarabia.

The German Air Force High Command (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL)), assigned to BARBAROSSA some 2,770 aircraft out of a total Air Force first-line strength of 4,300. Planes for the invasion of the Soviet Union were nearly 700 fewer than the number used in the much smaller French campaign; and the Air Force was, in the first five months of 1941, almost totally committed against Great Britain and would have to continue so on a reduced scale after BARBAROSSA began. Because of the strain the fighting in two widely separated theaters would impose on his resources and organization, the Commander in Chief, Air Force, Reichsmarschall Herman Goering, had strongly opposed the operation against the Soviet Union. The campaign in the Balkans in the spring of 1941, added a further complication, as it also did for some of the ground forces.

Because of the danger of giving the operation away by a sudden drop in the intensity of the attacks against Great Britain, the flying units could not be shifted east until the latest possible moment and then only after an elaborate radio deception had been arranged to give the impression that they were being redeployed for an invasion of England. In spite of that and the other problems, however, the German Air Force looked forward to the campaign with confidence. It had the advantage of first-rate equipment, combat experience, and surprise.

The air units deployed on the eastern frontier, between the Baltic and the Black Sea, were organized as First Air Force, supporting Army Group North; Second Air Force, supporting Army Group Center; and Fourth Air Force, supporting Army Group South. Fifth Air Force, its main mission the air defense of Norway, was to give modest support to the Army of Norway and Finnish Army forces operating out of Finland. In accordance with standard German practice, the relationship between the air forces and the army groups was strictly limited to co-operation and co-ordination.

The German Navy’s first concern in BARBAROSSA was to be maintaining control of the Baltic Sea. It had additional limited missions in the Arctic Ocean and the Black Sea, both of which the Navy High Command, (Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine (OKM)), believed could not be executed until after the air and land operations had eliminated the Soviet naval superiority. The Navy was also heavily engaged in operations against Great Britain, and the Commander in Chief ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- The Author

- Preface

- Chapter I: Invasion!

- Chapter II: Retreat

- Chapter III: Stalingrad, the Encirclement

- Chapter IV: Stalingrad, the Turning Point

- Chapter V: The Countermarch

- Chapter VI: The Center and the North

- Chapter VII: Operation ZITADELLE

- Chapter VIII: The First Soviet Summer Offensive

- Chapter IX: The Battle for the Dnepr Line

- Chapter X: The Rising Tide

- Chapter XI: Offensives on Both Flanks—the South Flank

- Chapter XII: Offensives on Both Flanks—the North Flank …

- Chapter XIII: Paying the Piper

- Chapter XIV: Prelude to Disaster

- Chapter XV: The Collapse of the Center

- Chapter XVI: The South Flank

- Chapter XVII: Retreat and Encirclement

- Chapter XVIII: Defeat in the North

- Chapter XIX: The January Offensive

- Chapter XX: The Defense of the Reich

- Chapter XXI: Berlin

- Chapter XXII: Conclusion

- Appendices