- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The story of an infantry officer on the Western Front, of the Fourth Battalion of the Coldstream Guards who was awarded the MC. At first he had a relatively safe posting but this preyed on his conscience and asked for front-line duty. This he experiencced in large meaure and his account is hugely well worth reading. The book ends with a moving description of the liberation of French towns which had been under German occupation for four years.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CONTENTS

Editor’s Introduction

Prologue

1. The Outbreak of War

2. The Belgian Field Hospital

3. Windsor, France and Robin’s Death

4. Winter in the Pas de Calais, 1915–16

5. Clairmarais Forest, March–May 1916

6. The Ypres Salient and the Somme, July–September 1916

7. Bitter Winter 1916–17

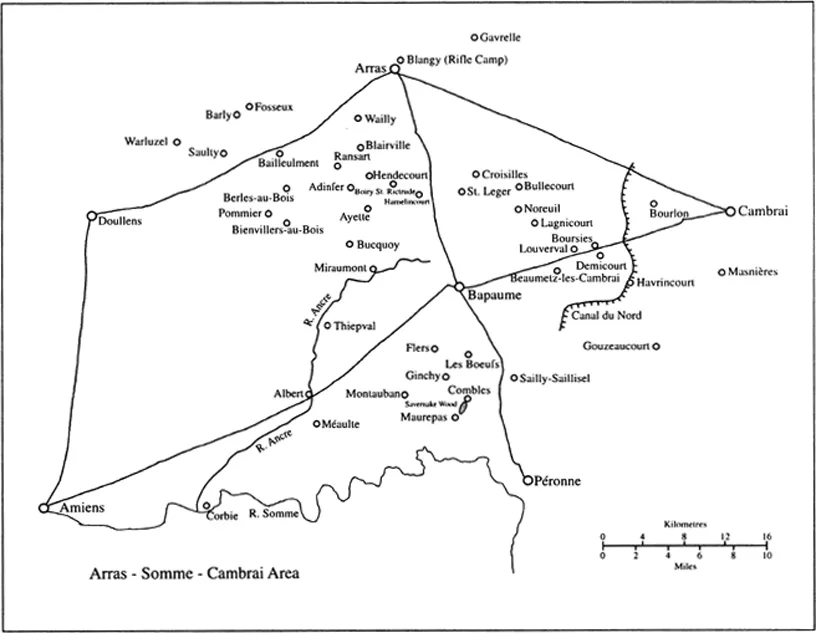

8. Spring 1917: Corbie – the Wood and the Tow-Path

9. Summer and Autumn 1917: Behind the Lines at Passchendaele

10. November–December 1917: The Battle of Cambrai

11. Winter and Spring 1918: The German Offensive

12. The Second Battalion, June–August 1918

13. Canal du Nord

14. The End of the War

Epilogue

Appendix 1. Robin’s Notebook; Last Letters and Death

Appendix 2. The Finding of Robin’s Body; Letters from George Bernard Shaw, Captain Lloyd, Private Wright and Rudyard Kipling

Appendix 3. Editor’s Postscript

Dramatis Personae

Index

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

In 1963, when he was 67, my father, Carlos Paton Blacker (known to most of his family and friends as ‘Pip’ or sometimes ‘CP’, and to whom I shall refer as CPB), started to write what he called his autobiography. After a preliminary chapter on his school days, he launched into an account of his experiences in the First World War, which started as soon as he left school. For this he had much material to draw on: he had written to his parents almost every day and they had preserved his letters; he also had the diaries which he had kept at the time, and many of the large-scale, cloth-bound maps, often showing the trenches and strong-points, which had been issued to officers, and one or two of which were still stained with his blood.

But as his account of the war became longer and longer, members of his family expressed the hope that his ‘autobiography’ would not be confined to this relatively short period of his life. His war experiences, we pointed out, were far from unique, and such as had already been vividly described by others, notably Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon. On the other hand his later life had held much of unusual interest: he had qualified in medicine and then specialized in psychiatry, so that he had seen the development of that subject from early days; he had also played a pioneer role in the birth control movement, which had likewise undergone enormous changes during his lifetime. But these suggestions met with a firm refusal: his ‘autobiography’ would go no further than November 1918. Eventually it took him longer to write than the war had lasted, and when finished it ran to some nine hundred pages of typescript. He took no steps to publish any of it.

He died in April 1975, aged 79. Soon after his death, one of his colleagues from the Maudsley Hospital, Dr Denis Leigh, visited our family home to collect material for an obituary of my father which he was writing for one of the medical journals. We showed him the nine hundred pages. He took one look at them and said: ‘It’s not an autobiography; it’s a catharsis.’

The literal meaning of the word catharsis is a ‘cleansing’, and the First World War was, in my father’s words, ‘a terrible period in the history of the world which cast its shadow on everyone who lived in it’. In his case the shadow was deepened by various factors. In the first place his heart was never in the war; he did not believe in Germany’s sole culpability for the start of hostilities and he could not participate in the ‘frenzy of hatred’ against Germans which gripped the great majority of British people. Secondly he undoubtedly suffered from feelings of guilt for having survived it. Indeed one side of him clearly wanted to be killed, and this death wish remained with him for the rest of his life. Only feelings such as these can explain some of his more anomalous actions. Why, for example, did he feel a compulsion to join the army at all, given that he had no desire to kill Germans, and he had been honourably failed in his medical examinations because of his eyesight? Why did he feel the need to apply for a transfer from the 4th to the 2nd Coldstream Battalion in the spring of 1918, thereby greatly increasing the risk of his own death? The arguments which he assembled against making such a move were cogent; those which he gives in its favour seem less convincing. In seeking, in his imagination, the advice of his dead brother, was he in fact plumbing the depths of his own subconscious?

Although, as I have said, he made no move to publish it, there were strong indications that he was not averse to the idea of publication. At one point he let his imagination run sufficiently wild as to speculate as to how any financial profits which might accrue from it could be devoted to the reconciliation of British and German ex-servicemen. But any publication clearly necessitated heavy editing of the original manuscript. Apart from its excessive length, his detailed re-living of the four years comprised descriptions of events which were, as he put it, ‘narrowly personal and of no interest to anyone but myself’. It has therefore been reduced by about half.

Yet what remains constitutes, I believe, a worthwhile contribution to the literature on World War I. It contains various features not readily found elsewhere: his own introspective reactions to the traumatic events in which he was involved; his shrewd character sketches of his fellow officers; his strange mystical experience on the banks of the River Somme; the poignant juxtaposition of the desolation wreaked by the war and his intense love of natural history, particularly birds and wild flowers, evoked by such places as the Clairmarais Forest and the wood on the hill above Corbie. Above all he believed that the whole war was a hideous mistake which should never have happened; if such mistakes are not to recur, nobody should be allowed to forget.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

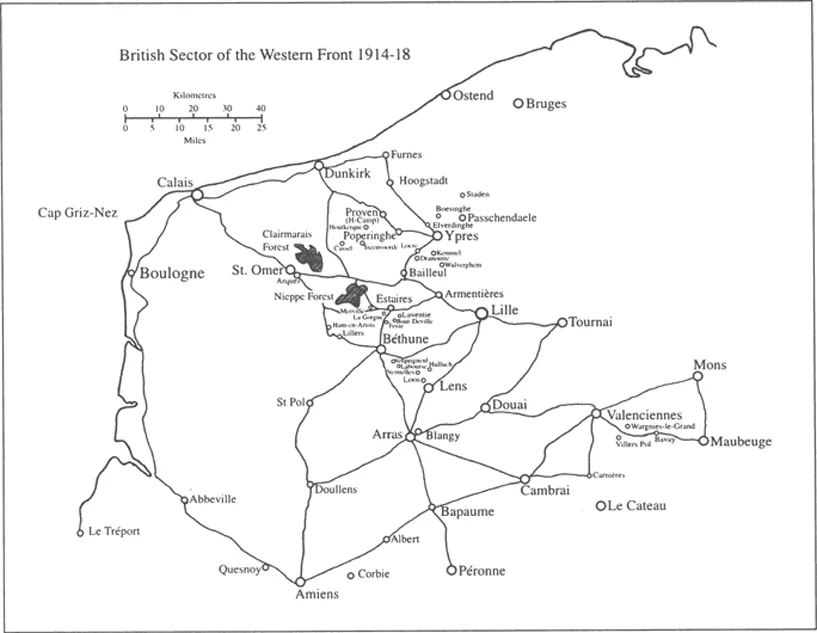

My father’s original manuscript was typed by the late Mrs Peggy Hope-Jones, but attempts to read it with scanners were unsuccessful, and I am greatly indebted to Huyette Shillingford for re-typing the relevant sections in WordPerfect; without her help the whole project might never have got off the ground. I am also grateful to Evelyn Dodd who assisted with the typing of the chapter on the Canal du Nord, and to Mary Gibson for compiling the index. Thanks are due too to the Audio-Visual and Printing Services of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for drawing the maps and reproducing the photographs. I am grateful to Lord Skelmersdale for the photograph of his father, to my cousin Alexandra Drossos for sending me copies of letters in her possession relating to Robin’s death, particularly that from my grandfather, Carlos Blacker, to his sister, Carmen Devaux (Alexandra’s grandmother) which I have quoted in Appendix 2, and to several people for reading the manuscript in draft, spotting typographical errors and making valuable suggestions: my sisters Carmen and Thetis Blacker, Michael Loewe, Peter Lowes and Carine Ronsmans; the last-named also accompanied me on the visit to the Somme in May 1998 when she provided valuable encouragement and support.

I also wish to acknowledge with thanks the Bernard F. Burgunder Collection of George Bernard Shaw, Division of Rare Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, and The Society of Authors, on behalf of the Bernard Shaw Estate, for permission to reproduce the letter from Bernard Shaw in Appendix 2. I am indebted to Major and Mrs Holt for finding and sending me the transcript of letter which my father wrote to Rudyard Kipling on 13 October 1915. Finally I want to record my warm thanks to Mr J. Robert Maguire for sending me, and giving me permission to use, the Rudyard Kipling letter in Appendix 2, for the many things which he has told us about our own family which we did not previously know, and for his encouragement and stimulus to pursue the task of editing my father’s manuscript.

PROLOGUE

CPB was born in Paris on 8 December 1895. His father, Carlos Blacker, (who features significantly in this story) was the son of an English businessman, John Blacker1, and a Spanish Peruvian mother, Carmen, née Espantoso. Carlos was a gentleman of leisure all his life; he never seems to have made a serious attempt to earn his living, and his only foray into the world of business was catastrophic: he lost all his money and was declared bankrupt in 1894. This disaster also led to a rupture with one of his best friends, the Duke of Newcastle, who in a fit of temper accused him of cheating at cards. The charge was wholly unfounded and years later Newcastle apologized. But in the meantime Carlos was faced with a dilemma. He was called upon to defend his honour, and since duelling was illegal he was expected to sue his former friend for libel; failure to do so was regarded as being tantamount to an admission of guilt. But not only would such a step involve him in expenses which he could not afford, the whole prospect was also totally abhorrent. Rather than proceed with it he left England to live in self-imposed exile on the Continent. Thus it was that CPB was born in Paris, and he did not in fact set foot in this country until he was nine years old. Later, when both the sons were at boarding school in England, the family moved back to this country to live in a house called Vane Tower in Torquay.

Carlos was a brilliant linguist with refined tastes and many varied interests, and counted among his friends distinguished literary figures including Oscar Wilde, Anatole France and George Bernard Shaw. He had been painfully involved in the Dreyfus Case in the late 1890’s2. His sister, Carmen, and her husband, Charles Devaux, had taken up residence in Germany, and their son, Ernest, was an officer in the German army in World War I. Thus CPB had a first cousin fighting on the other side.

CPB’s mother, Caroline, was American, the daughter of Daniel Frost of St Louis, who had been a general in the Confederate army in the Civil War. She had eloped from America to marry Carlos against her father’s wishes. They were married in February 1895. Apart from CPB, they had only one other child, Robin, born in June 1897, who also features largely in this story.

CPB’s aunt Carmen lived in Freiburg in south Germany, and substantial periods of his early childhood were spent there. They were happy times and they influenced his attitude towards Germans for the rest of his life, as he describes:

My father, who influenced me much in my feelings during early days and in my later sympathies, did not conceal his love of Freiburg and the Black Forest which he looked upon as a second home. Indeed, my earliest memories are of my aunt’s house from which my small brother and I used to be taken for daily walks by our white-haired Irish nurse to whom, despite her occasional severity, we were devoted. Our most usual outing was a path winding up a fairly steep hill which overlooked Freiburg and was known to us as The Schlossberg. My earliest out-of-door memories are of snow-laden fir trees bordering an ice-covered rockface on our left, and of frost-encrusted railings of wire netting bordering the path. My father, walking at a faster pace, would sometimes follow us to the summit of The Schlossberg, where, close to a seat, we would prepare a low heap of snow on which a sort of fire ceremony was enacted. My father would produce from his pocket a box of elongated fusee-type matches, a few of which we would stick into the snow heap and light, thus producing a minor fireworks display. In the course of these walks Robin and I were encouraged to ask my father children’s questions, mostly unanswerable – such as, why does fire melt snow? Why do some trees bear soft fruit you can eat and others dry stiff cones which you can’t? On these questions my father would deliberate and give replies within the range of our understanding.

Another indoor feature of the daily routine in my aunt’s house was nursery prayers, morning and evening, over which our Catholic Irish nurse presided. Robin and I knelt on each side of her by her bedside. There we recited the Lord’s Prayer and said the Hail Mary. Other topics of religious or moral import were subjected to bedside discussion, including the Ten Commandments, not all of which were as immediately understandable to small children, as the one about honouring one’s parents. Soon afterwards I broached the subject with my father during one of our walks up The Schlossberg. My father had a quiet voice and very gentle manners. He could attune himself to children of different ages and knew exactly how to talk to them. He dealt with our questions about the Ten Commandments by telling Robin and me that these Commandments were directed to different people. Some were specially meant for children and others were more for grown-ups, but that in due course we would understand them all and profit by them. In the meanwhile we could take it that all ten could be summed up in one comprehensive Commandment, which, if acted on by everyone, would make the world a much better place than it was. What, we asked expectantly, was this Commandment? My father hesitated a few seconds before answering. He then spoke the following two words: ‘Be kind,’ he said. After all these years I clearly remember the moment when he pronounced these words. It was a cold evening and we were standing near the seat at the top of The Schlossberg. My father was smiling with pleasure over what he was saying, and I saw his face in profile. His dark moustache was touched white with frost. He was wearing gloves and a cap. Robin and I wore mittens and woollen head coverings. ‘Be kind to one another, especially to children younger than yourselves,’ he said, and, as he spoke, my father looked to us to be the kindest, wisest and best of men. Something of this well-remembered visual impression remained with me throughout the ensuing war, and remains still.

These and other early experiences, which I need not describe, made it natural for us to regard Freiburg and its i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Aftermath

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Have You Forgotten Yet? by John Blacker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.