eBook - ePub

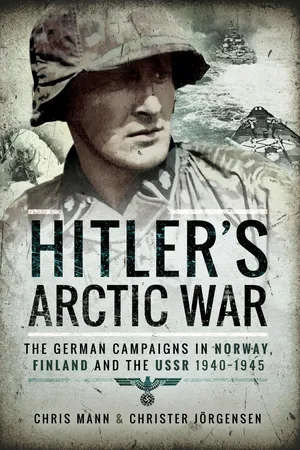

Hitler's Arctic War

The German Campaigns in Norway, Finland and the USSR 1940–1945

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hitler's Arctic War

The German Campaigns in Norway, Finland and the USSR 1940–1945

About this book

A groundbreaking study of how war was waged in the far north of Finland, Norway, and the Soviet Union: "Well-illustrated and organized." —

WWII History

According to Lieutenant-General Waldemar Erfurth of the German Army, the General Staff had taken no interest in the military history of the north and east of Europe, failing to imagine that someday German divisions might have to fight through the winter in northern Karelia and on the Murmansk coast. Yet, the German Army's first campaign in the far north was a great success. Between April and June 1940, with less than 20,000 men, they seized Norway, a state of three million people, with minimal losses.

Hitler's Arctic War is a study of the campaign waged by the Germans on the northern periphery of Europe between 1940 and 1945. As the book makes clear, the emphasis was on small-unit actions, with soldiers carrying everything they needed—food, ammunition, and medical supplies—on their backs. The terrain placed limitations on the use of tanks and heavy artillery, while lack of airfields restricted the employment of aircraft.

Also included is a chapter on the campaign fought by Luftwaffe aircraft and Kriegsmarine ships and submarines against the Allied convoys supplying the Soviet Union with aid. Yet, the book asserts, Wehrmacht resources committed to Norway and Finland were ultimately an unnecessary drain on the German war effort.

"Lavishly furnished with photographs . . . a gripping introduction to this very different war." —Pegasus Archive

"The authors effectively explain how soldiers dealt with the arctic conditions and the extensive hardships they endured while fighting at the top of the Continent . . . a good general history of the various operations in Norway, Finland, and the Soviet Union during the war." —WWII History

According to Lieutenant-General Waldemar Erfurth of the German Army, the General Staff had taken no interest in the military history of the north and east of Europe, failing to imagine that someday German divisions might have to fight through the winter in northern Karelia and on the Murmansk coast. Yet, the German Army's first campaign in the far north was a great success. Between April and June 1940, with less than 20,000 men, they seized Norway, a state of three million people, with minimal losses.

Hitler's Arctic War is a study of the campaign waged by the Germans on the northern periphery of Europe between 1940 and 1945. As the book makes clear, the emphasis was on small-unit actions, with soldiers carrying everything they needed—food, ammunition, and medical supplies—on their backs. The terrain placed limitations on the use of tanks and heavy artillery, while lack of airfields restricted the employment of aircraft.

Also included is a chapter on the campaign fought by Luftwaffe aircraft and Kriegsmarine ships and submarines against the Allied convoys supplying the Soviet Union with aid. Yet, the book asserts, Wehrmacht resources committed to Norway and Finland were ultimately an unnecessary drain on the German war effort.

"Lavishly furnished with photographs . . . a gripping introduction to this very different war." —Pegasus Archive

"The authors effectively explain how soldiers dealt with the arctic conditions and the extensive hardships they endured while fighting at the top of the Continent . . . a good general history of the various operations in Norway, Finland, and the Soviet Union during the war." —WWII History

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hitler's Arctic War by Chris Mann,Christer Jörgensen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

GERMANY, FINLAND AND THE WINTER WAR

Finland, like other Scandinavian countries, endeavoured to remain neutral in international affairs. However, political changes within Germany and the USSR would lead to the Winter War with the Soviet Union.

World War II came to Scandinavia on 30 November 1939. Like her Scandinavian neighbours Norway and Sweden, Finland had stated her neutrality on the outbreak of war in September 1939, but declarations of neutrality counted for little with Europe's dictators. The Soviet invasion of Finland was a direct consequence of German diplomacy; it is unlikely Stalin would have moved against the Finns without the assurance of German non-intervention provided by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939. However, Germany had long-standing links with Finland, and a Soviet victory would clearly alter the balance of power in the Baltic, perhaps even threaten German iron ore supplies from Sweden, and give the Western Allies (Great Britain and France) an opportunity to dabble in Scandinavian affairs. Hitler’s reasons for giving Stalin a free hand in Finland lay largely in the free hand it gave him in the West. The Germans maintained an aloof neutrality in the Winter War, but they noted with interest the performance of the Red Army and their analysis of this would have profound implications for the future. Given the antecedents of German-Finnish relations, this stance might appear strange. German military involvement with Finland dated back to the last years of World War I, and resulted in the establishment of important links between the Finnish and Germany militaries.

Dressed in winter camouflage uniforms, a Finnish Army machinegun team prepares to meet a Red Army attack during the Winter War, 8 December 1939.

Russian Bolshevik leader Lenin (left) hoped that Finland would succumb to a communist revolution and then seek union with Russia. The woman on the right is Lenin’s wife.

Finland had been part of the Russian Empire since 1809. Although initially given considerable autonomy, attempts at Russification in the early twentieth century had caused considerable resentment. So when the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd overthrew the Provisional Government in November 1917, the Finnish leadership saw the opportunity to gain their country’s independence. On 4 December 1917, Pehr Albin Svinhufvud presented the Eduskunta, the Finnish parliament, with what was later called the Declaration of Independence, which was passed two days later.

German troops, part of the Baltic Division, exchange fire with Red forces in Helsinki during the Finnish Civil War.

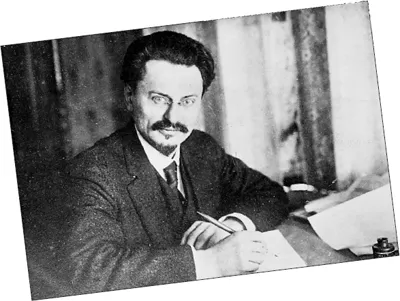

Russian Commissar for War, Leon Trotsky, urged Finnish socialists to seize power in their own country.

The new government’s main concern was to achieve foreign recognition of Finnish independence. The Germans, who had enjoyed a long period of success against Russia in 1916–17, were keen to foster the separatist tendencies of the nationalities within the Russian Empire, and thereby undermine its ability to fight. So the Germans approved of Finland’s actions and the Finns were eager for German support. However, even Germany was unwilling to recognize Finland before Russia did. Sweden, Finland’s neighbour, and the rest of Western Europe concurred. Germany therefore insisted that Finland approach Lenin’s Bolshevik Government in Petrograd, as clearly this was the only central authority in Russia worth the name. Indeed, the Germans were at the time negotiating with the Bolsheviks for a Russian exit from World War I.

A delegation of Finnish socialists met Lenin on 27 December. He promised to recognize Finnish independence, and the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party approved his decision in principle the following day. Lenin reasoned that a Finnish revolution would soon follow and his Commissar for War, Leon Trotsky, advised them to take swift action to seize power. The Finnish Government was similarly told that the Bolsheviks would accept Finnish independence, and a delegation headed by Svinhufvud gained Lenin’s acceptance on 31 December. This was ratified by the Central Committee on 4 January 1918. Lenin had been forced to deal with the Finnish bourgeois government because the Finnish socialists held similar views on independence. Lenin fully expected that he would soon be dealing with a Finnish workers’ government, which, in time no doubt, would request union as a republic in the new Russian Federation of Nations.1

Imperial Germany had encouraged the Finns to press for independence, although official recognition did not come until 6 January 1918. German strategy dictated that Finnish territory could be used to further the isolation of Russia. There would, no doubt, be useful trading opportunities too. France had recognized the Finnish declaration two days earlier, desperate not to drive the new nation into German hands. However, France was too cut off from the northeastern Baltic to be of any great use to Finland in the struggle to maintain the latter’s fledgling nationhood. Geography, pure and simple, dictated to whom the Finnish Government would have to turn.

A machine-gun company from the Baltic Division advances against Red Guards near Hanko.

The Finnish people, although united in their desire for independence, were less unified in their ideas for Finland’s future. The gulf between the bourgeois Finnish Government and the Finnish left grew. The Eduskunta granted the government full power to establish an army and restore order, as the country had been racked with strikes and rioting. This was viewed as a direct challenge by the Finnish labour movement, and did much to bring the radicals and moderates on the left together. Both sides began arming rapidly. The gun-running of the left’s militia units – the so-called Red Guards – between Viipuri and Petrograd led to full-scale fighting on the Karelian Isthmus on 19 January.2 The fighting soon spread. On 27–28 January the Red Guards seized Helsinki, and elements of the government managed to flee to Vaasa and set up a rump administration in the White – as the government’s forces were known – heartland of Ostrobothnia.

General von der Goltz commanded the German Baltic Division in the Finnish Civil War.

THE FINNISH CIVIL WAR

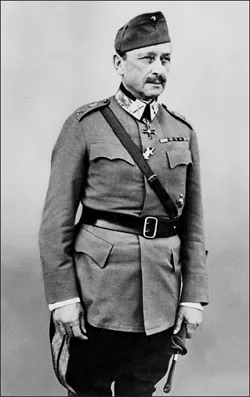

The Finnish Civil War was a war of frontlines and conventional offensives. The Whites held Northern Finland, Ostrobothnia and Karelia, and the Reds controlled most of the major cities, industrial centres and the south. The country was roughly divided on a line from the Gulf of Bothnia to Lake Ladoga. The size of forces was fairly well matched, probably in the region of 70,000 combatants each, although estimates vary. The Reds were poorly trained, equipped and led for the most part, but had the dubious advantage of the half-hearted support of the Russian troops that remained in Finland. These were more useful as a source of equipment. The Whites had similar deficiencies in training and equipment, and their quality of leadership varied. They were, however, commanded by a number of Tsarist-trained Finnish officers and Swedish volunteers, and were led by one Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, a general who had served in the Imperial Russian Army and was easily the most able commander of the civil war. The one first-class formation available to the Whites was the 27th Jäger Battalion. As part of the wider movement for Finnish independence, a number of Finnish volunteers undertook military training at Lockstedt in Germany under special arrangements with the German authorities. The number of volunteers swelled, and a Jäger (light infantry) battalion was formed as part of the Imperial German Army in May 1916. It saw service in the Kurland area against the Russian Army in 1916–17, but as the situation in Finland worsened the unit returned, landing at Vaasa in February 1918. Mannerheim promptly broke the unit up, thus providing a cadre of experienced officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) which he put to work training his army.

Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s Minister for Foreign Affairs. In August 1939 he went to Moscow to finalize the non-aggression treaty with Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Although Mannerheim’s early campaigns met with success, the war was shortened by German intervention, which the Finnish commander considered unnecessary and undesirable. He accepted that German involvement saved lives, but believed it undermined the achievement of Finnish independence and this motivated him to drive his advance forward as quickly as possible.3 Two White government officials in Berlin had requested German military aid in early February without official sanction. A week later Germany announced that it would accede to the Finnish request, in effect, inviting itself to the assistance of Finland. On hearing the news, Mannerheim threatened to resign and the government was somewhat perplexed to find itself forced to sign three somewhat disadvantageous agreements: a peace treaty forbidding Finland to deal with other nations without German approval; a trade and maritime agreement granting Germany economic preference; and an undertaking that Finland would pay for the costs of all German military intervention.4 Even in 1918, Finland was learning that German aid did not come without serious consequences. Given his government’s acceptance Mannerheim “loyally bowed to the inevitable.”5 The main German force, General Rüdiger von der Goltz’s Baltic Division of some 11,000 men, landed in Finland on 3 April 1918. Three thousand more arrived four days later. The capture of Helsinki followed soon after, and the last major city in Red hands fell on 26 April, with the final surrender occurring in mid-May on the Karelian Isthmus.

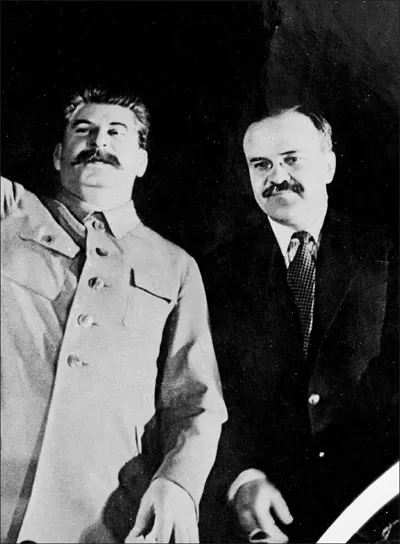

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin (left) with his Foreign Minister Molotov. The latter signed the nonaggression treaty with Nazi Germany on 23 August 1939, thus isolating Finland effectively.

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, Finnish field marshal, statesman and national hero. Born a Russian national, he rose to the rank of major-general in the Imperial Russian Army.

Mannerheim had pushed the border with Russia in Karelia eastwards and the unofficial fighting over where the frontier with Bolshevik Russia would lay rumbled on through 1918, 1919 and into 1920. However, Finland’s relationship with Germany and her obvious ambitions in the north had serious implications for Finland’s relations with the Western Allies. The Germans were pressing the Finns with offers of aid in capturing the rest of Karelia if they helped a German thrust towards the British base at Murmansk (British and Finnish troops had already clashed at Petsamo). Furthermore, the treaties signed with the Germans did more than just place the young state under German patronage, they offered the prospect of German economic penetration that would effectively turn Finland into a German colony.6 The Finns had also agreed to have a German prince elected king. Inevitably, German influence extended deep into military affairs, and in May 1918 the government had instructed Mannerheim that the army should be reformed along German lines by German officers, essentially handing the responsibility of Finland’s defence over to Germany. Mannerheim promptly resigned.

The Russo-German non-aggression treaty allowed Hitler to crush Poland in a three-week campaign. These are German troops in Poland in September 1939.

Until about July 1918, this pro-German policy made considerable sense. Germany was the dominant power in Eastern Europe, and until the failure of the Ludendorff Offensive on the Western Front that month might possibly have emerged victorious. However, Finland’s German orientation was rudely brought to an end by the defeat of Imperial Germany by the Western Allies in November 1918. A rapid change in direction had to follow; Prince Friedrich Karl of Hesse renounced his claim to the Finnish throne and the last German troops left Finnish soil in mid- December. The Western Allies were conciliatory, keen to use Finland in their fight against Bolshevik Russia. However, Western recognition of Finnish statehood only followed with the failure of this policy. The Finns were able to conclude a peace with Lenin’s government, which was in the midst of the Russo-Polish War and was eager to limit the number of prospective enemies on Russia’s borders. The Treaty of Tartu, signed on 14 October 1920, was little more than a settlement of frontiers and certainly did not establish a basis for friendly relations. Indeed, the treaty was probably too advantageous for Finland, placin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Germany, Finland and the Winter War

- Chapter 2 The Invasion of Norway

- Chapter 3 Hitler’s Barbarossa Venture

- Chapter 4 Stalemate on the Frozen Front

- Chapter 5 The War on the Arctic Convoys

- Chapter 6 Red Storm – Stalin’s Revenge

- Chapter 7 The Price of Occupation

- Conclusion

- Chapter Notes

- Bibliography