- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medieval Siege and Siegecraft

About this book

A fascinating survey of the defining activity of warfare between rival power centers in the Middle Ages from the author of

A Brief History of the Crusades.

Great sieges changed the course of medieval history, yet siege warfare, the dominant military activity of the period, is rarely given the attention it deserves. Geoffrey Hindley's highly readable new account of this vital but neglected aspect of medieval warfare looks at the subject from every angle. He traces the development of fortifications and siege equipment, explores the psychological dimension and considers the parts played by women and camp followers. He also shows siege tactics in action through a selection of vivid case studies of famous sieges taken from the history of medieval Europe and the Holy Land. His stimulating and accessible study will be fascinating reading for medieval specialists and for anyone who is interested in the history of warfare.

"For those interested in a fuller understanding of medieval warfare, covering the years 500 to 1500 C.E., this book should be square one . . . the extremely readable results are recommended." —Library Journal

Great sieges changed the course of medieval history, yet siege warfare, the dominant military activity of the period, is rarely given the attention it deserves. Geoffrey Hindley's highly readable new account of this vital but neglected aspect of medieval warfare looks at the subject from every angle. He traces the development of fortifications and siege equipment, explores the psychological dimension and considers the parts played by women and camp followers. He also shows siege tactics in action through a selection of vivid case studies of famous sieges taken from the history of medieval Europe and the Holy Land. His stimulating and accessible study will be fascinating reading for medieval specialists and for anyone who is interested in the history of warfare.

"For those interested in a fuller understanding of medieval warfare, covering the years 500 to 1500 C.E., this book should be square one . . . the extremely readable results are recommended." —Library Journal

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Fortified Towns and Cities

‘Happy is that city which in time of peace thinks of war.’

Robert Burton (d.1640), citing an inscription in the Arsenal, Venice

From Jericho to Troy, medieval Europe knew a tradition of siege warfare as part of its antiquity. In fact, the siege, a static conflict to capture a strong point, was a type of combat made possible only by the rise of city culture. According to the words of the spiritual, ‘When Joshua fit the Battle of Jericho … the walls came a tumbling down’. The biblical text records that the walls collapsed at the sound of the war trumpets of the Hebrew army. This must have been about the easiest victory in the history of siege warfare – and also one of the first.

Naturally the hand of God played its part in the fall of Jericho. Divine intervention has often been invoked by the religious or the resigned to account for the course of events in war. As he handed over the Alhambra to its Christian victors in January 1492, Abu Abdullah (‘Boabdil’), last king of Granada, is said to have recognized the hand of Allah in his disaster and to have acknowledged the sins of the Muslims as the cause of the deity’s anger. When, in June 774, Charles the Great, king of the Franks (in French Charlemagne, in German Karl der Grosse) took the city of Pavia, capital of the Lombard kingdom of north Italy, and so laid the foundation for his later claim to empire, it cost his army the rigours of an eight-month siege. In the next century pious clerics attributed the conquest to a miraculous five-day campaign in which not a drop of blood was shed and during which the Frankish army ‘built a basilica in which they might render service to almighty God outside the walls if they might not do so within’. Indeed, within twelve hours they erected a church complete with ceilings to its roofs and religious painting for its walls of such dimensions that all who saw it vowed it could not have been built in less than twelve months. Confronted with this marvel ‘that party among the citizens which had favoured surrender prevailed’. But outside the world of legend or the pages of holy books, siege warfare was a grinding business as old as city culture itself.

The exact dates of Joshua, indeed his very existence, are uncertain, but after excavations in the 1950s led by the British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon it seems that Jericho is one of the world’s most ancient cities, and is to be associated with the beginnings of the agricultural revolution dated to about the seventh millennium BC. That revolution, which meant the creation and amassing of food surpluses, provided the conditions for the birth of city culture with the storage facilities to secure those surpluses; the administrative personnel to administer those surpluses; and the need for a warrior class to defend them – in short the groundwork for city-based culture or ‘civilization’ (from the Latin word civis, ‘a citizen’). Thus siege warfare, the assault on and the defence of those surpluses, can indeed be seen as the earliest form of organized warfare – as distinct from the raiding-party rivalries of hunter-gatherer tribes.

Troy VIIa: c. 1250 BC

Homeric legend holds that the war against Troy, which scholarly opinion has placed some time about the year 1250 BC (i.e. the era of Troy VIIa), was the next most famous siege after Jericho. According to Homer, this siege lasted ten years. Archaeology has shown that over millennia the site associated with Troy, in north-western Turkish Anatolia, a few miles inland from the Dardanelles strait, was occupied by a number of cities and subject to more than one siege. The place was a stronghold on a trade route running along the northern coast of Anatolia from Asia to the Dardanelles and crossing into Europe. It was prosperous and powerful and presumably levied tolls on the shipping through the straits, such as Greek merchants plying to ports in the Black Sea.

The siege was prompted when Prince Paris of Troy abducted Helen, wife of King Menelaus of Sparta. He appealed to the other Greek rulers; they joined forces to avenge him and force Troy to return Helen, reputed the most beautiful woman in the world. It is a good story, and anthropologists expert in early cultures suggest that women were often ‘trophy-traded’.

Whether or not it lasted ten years, the siege would, in the nature of things, have lasted a long time. At the start of the conflict, at least, the Greeks had no siege-engines, while the Trojans’ battlements were virtually impregnable. The Greeks made a camp on the shore, and it was sometimes besieged by the Trojans. For a long time Achilles, one of the chief leaders in the Greek army, refused to fight because he claimed he had been insulted in the division of the spoil in a successful raid. Many times it seemed that the Greeks would never take the city. In fact, according to Homer, they did so only by deception.

The new cities – rich and above all comparatively well fed, filled with houses, palaces and temples, crammed with luxury garments and precious objects, and packed with people ripe for enslavement – made mouth-watering targets. But if they were well worth attacking, they were also well provided with defences. Lightly clad tribesmen and even armoured soldiery learnt that success against such objectives called for new ways of fighting, the development of specialized equipment and weaponry, and tactical thinking that developed over time. Unlike the average field battle, a siege did not observe the Aristotelian dramatic unity of time in which the action of a play should ideally be confined to the hours between sunrise and sunset. It was a conflict of weeks, months or even years’ duration. Psychological warfare, even simple deception, could be decisive tools to undermine the morale of the garrison or to unbalance the calculations of the commander.

All the world knows that Troy fell to a trick. The Greeks were notorious in the ancient world for their trickery. In his great poem about Prince Aeneas of Troy, the Aeneid, the Roman poet Virgil had one of his characters say, ‘timeo Danaos et dona ferentis’, ‘I fear the Greeks (the ‘Danaians’) even when they come bearing gifts’. In the tenth year of the siege, advised by the wily Odysseus (Ulysses), King Agamemnon ordered the building of a massive wooden horse to be left on the plain outside the walls of Troy as if as an offering to the gods. Then the Greek army drew back as if abandoning the siege. The Trojans pulled the wooden monster into the city in triumph. But inside its belly was a detachment of Greek soldiers. That night the soldiers slipped out and opened the city gates to their army which had come back under cover of darkness. Troy was taken utterly by surprise and destroyed, its buildings put to the torch and its citizens put to the sword. The fortunate ones were sent to the slave markets and some may even have made good their escape. One such, Prince Aeneas, voyaged to Italy, where he founded Lavinium, forerunner to Rome. The siege of Troy was clearly an event of world historical importance – at least in Roman legend.

Fire and sword were to be expected by a city that failed in its defence. In exceptional circumstances death might not follow. A Russian visitor to Constantinople, ‘the second Rome’, during the civil turmoil that accompanied the dying decades of the Byzantine Empire witnessed the night-time breach of the city in 1390 by partisans of the line of Emperor Andronikos IV and his son John VII. The streets and squares were in uproar as foot-soldiers and horsemen dashed to and fro, lanterns aloft, among terrified citizenry crowding out on to the streets ‘in their nightclothes’. Brandishing weapons and with arrows notched on bow strings, the soldiery shouted ‘Long live Andronikos!’ and the people – men women and even the children – shouted in response, ‘Long live Andronikos!’, since any who held back even for an instant were threatened with death. In fact, the Russian witness, Ignatius of Smolensk, saw ‘none slain anywhere, such was the fear inspired by the weapons’.

Academic opinion has long accepted that Homer’s epic the Iliad is a poetic retelling of actual historic episodes. Even so, the story of the Trojan horse seems rather far-fetched: did the Trojans really accept the Greek story that it was a gift to the goddess Athena that would make their city impregnable if they took it in? But perhaps the legend represents a poetic memory of an actual structure: not a model horse but a mobile siege-tower, of the kind known in Assyrian warfare. The Roman army used siege-towers, massive wooden structures on wheels, with ladders inside for the attacking force to climb to bring it to a platform level with the wall of the fortress or city.

Homer had only legends to work with, and the ancient Greeks had some strange legends. When they first encountered tribes that fought on horseback they were so astonished that they are said to have thought they had found a monster, half-man, half-horse – hence the legend of the centaurs. May be the Greek machine at Troy was just a primitive siege-tower dubbed ‘the horse’ by Greek soldiers.

Heroism of the populace

Just as Troy, site of the most famous siege of ancient history, was on the southern coast of the Sea of Marmara in modern Turkey, so the most famous siege of medieval history was that of Constantinople in 1453 at the other end of that sea. Inaugurated in 330 by Emperor Constantine the Great on the site of the ancient Greek port of Byzantion, it occupied a rough triangle of territory between the Sea of Marmara to the south and the great natural harbour of the sea inlet known as the Golden Horn to the north. It was protected by some fourteen miles of fortifications. Walls ran for five and half miles along the coast, in places rising direct from the shore line and protected by rapid, treacherous currents that made any attack hazardous in the extreme. Another three and a half lines of wall rose behind the docks and warehouses of the waterfront of the Golden Horn. The entrance to the great harbour was guarded at the time of the siege by a massive boom to block the entrance of the Turkish fleet.

The defences of the city to the landward side were the most formidable in the Western world. Built during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II in the 410s, under the direction of the imperial minister Anthemius, they had been maintained throughout their long history and had never been breached. They comprised a four-mile triple defensive system of a moat 60 feet wide, an outer wall with regularly spaced towers of about 45 feet in height and an inner wall 14 feet thick, 40 feet high and with towers some 60 feet high. On 2 April 1453 the Turkish army of Sultan Mehmet II encamped about midway along the walls at the St Romanos gate and began to deploy its artillery pieces.

And just as the siege of Troy entered the world of legend so the events of 1453 (see Chapter 6) would acquire almost mythical stature. Well into the sixteenth century chroniclers of the siege mention the participation of men whose presence is in fact difficult to substantiate, and embellish their accounts with feats of heroism that may or may not have taken place. ‘To have been present at the fall, to have fought bravely at the fall, to be related to someone who had fought bravely at the fall,’ writes Mark Bartusis in his book The Late Byzantine Army (2003), ‘were marks of distinction that could be supplied by an obliging chronicler’.

Local patriotism was often important in the morale of the defenders and so a factor in the military outcome. When, early in 1247 Parma had abandoned its allegiance to Emperor Frederick II and aligned itself, like other cities of the Po valley, with Milan in opposition, it knew that it faced a large and professional imperial army, recruited from the best mercenary troops money could buy. But the Parmese had been determined to make good their independence.

In fact, the city’s defection from the imperial cause had been engineered by Cardinal Gregory of Montelongo, the papal commander responsible for its defence, under cover of festivities being prepared for a great society wedding by the imperial party. The cardinal had connived with anti-imperial exiles who, taking advantage of the distraction of public opinion, returned in force and seized the family towers of their opponents. Having won control of the city they next reinforced the defences, erecting palisades and digging a network of trenches. Their rivals in the city establishment were outmanoeuvred, but public opinion was in favour of the new regime. As a result, the cardinal found himself at the head of a body of ‘citizen soldiers deeply concerned for the safety of their city and for their own freedom’. We have already seen how they played a triumphant role in the last days of the campaign. No doubt a learned churchman, the cardinal, in the shrewd estimate of the contemporary chronicler from Parma, Fra Salimbene, was also ‘learned in war’ (‘doctus ad bellum’) and skilled in the arts of dissimulation.

In June, aware that the imperial army was preparing for a protracted siege, Montelongo appealed urgently to the papal emissary for reinforcements – with no result. Facing slow starvation the patriotic commitment of the citizenry began to wilt. But the refurbished defences proved more than a match for the imperial forces, and early in November allies from Mantua and Ferrara managed to force the blockade with desperately needed supplies.

Still the siege dragged on. With the approach of autumn, work began on Emperor Frederick’s ‘siege city’ of Victoria. The reinforcements looked for by the citizens had failed to appear; rumour said that the pope’s agent in Lombardy was in fact in a secret agreement with Frederick. Perhaps he was and perhaps it was for this reason that the emperor felt free to go hunting. But the local patriotism of the Parmese won the day. Two centuries later similar heroism by the populace of Constantinople could not hold out against the assault of the Muslim conqueror, and that siege ended in defeat and the consolidation of the enemy religion in the Christian metropolis.

CHAPTER TWO

Strong Points in a Landscape

‘Our castle’s strength will laugh a siege to scorn …’

Shakespeare, Macbeth

No structure better embodies the title of this chapter than the legendary crusader castle Krak des Chevaliers. Atop its fortified hill dominating the Homs gap through the mountains between the main Syrian desert and the coast, it still commands the awed respect of the visitor; with the progressive stages of the building programme that created it in the twelfth century it surely appeared as the culmination of the castle designers’ art in the Middle Eastern theatre of war. Standing at Qal’at al-Hisn in Syria near the northern border of Lebanon, in the site of the Castle of the Knights, on a spur of black basalt rock between two converging wadis, it was often known to Arab writers as the Castle of the Kurds because at the time of the arrival of the crusaders it was held by a Kurdish garrison. By the 1130s it was in the hands of the counts of Tripoli, but in 1144 Count Raymond II ceded the fortress and its rich hinterland to the military order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, the Knights Hospitaller. They made various modifications in the 1140s, then, in 1202, an earthquake necessitated an extensive rebuild; today the inner enceinte is essentially the result.

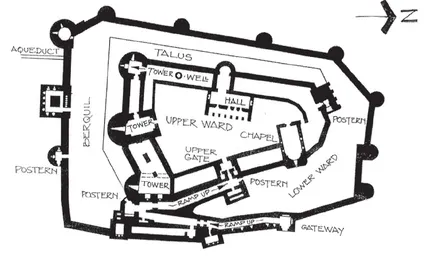

Sketch plan of Krak des Chevaliers (on the border of modern Lebanon). Gordon Monaghan

Arguably the greatest military structure to survive from the Middle Ages, Krak is awesome in its strength and complexity of design. The inner curtain wall follows the contour of the spur on which the building stands. The main entrance was by way of a gate approached by a zig-zag path up a steep escarpment. Any attempt at a direct assault meant scrambling up the steep and rugged slope, while to follow the winding path in column meant crossing and recrossing the concentrated fire from the walls of the fortress. An enemy who successfully pierced the gate in the outer curtain wall found himself in a covered passage known as the great ramp, heading up a path flanked by loopholes for archers, pierced by roof holes for the deposit of missiles and liquid fire and broken halfway along its length by a hairpin bend bent back on itself which then led to the upper main gate. Attacking from the south meant crossing a moat before scaling a massive wall defended by a sloping masonry glacis. Should that outer enceinte be breached, the attackers confronted a second water obstacle, the berquil or reservoir, over which lowered three massive towers defended by a second glacis whose dimensions were only revealed after the outer wall had been pierced. The place could house a garrison of 2,000 men in adequate accommodation with storage for provisions and water to match.

The soaring vaults of the great hall on the west side of the courtyard with its carved corbels, whose leaf shapes seem to recall the foliage of European woodland rather than the actual, arid setting of the place, provided a dignified setting when the consistory of the Order held its assembly here. In peacetime the chapel was the centre of castle life. A large and elaborate building in the Romanesque style, its east end chevet projects a few feet through the curtain wall to form a defensive tower. During its 130 years as a crusader bastion it withstood twelve sieges and repelled an attack by Saladin. The final and victorious siege achieved by the Egyptian army of the Mongol-born sultan Baibars (the name means ‘panther’) began on the morning of 3 March 1271 with the occupation of the township that had grown up below the castle walls. Heavy rains delayed the assault on the fortifications by some three weeks. The first outwork was easily taken and the sultan ordered heavy mining of the great south-west tower of the outer enceinte. But its collapse only revealed the full dimensions of the fearsome inner defences. These, however, were not put to the test since the sultan resorted to trickery, described in Chapter 9.

The defence of property

According to the French anarchist philosopher Pierre Joseph Proudhon, writing in 1840, ‘property is theft’. Perhaps he had in mind the vast properties of the French landowning classes, which originated under the old monarchy but survived the French Revolution or were to be matched by grants awarded under Napoleon’s empire or the Bourbons’ legitimist kingdom.

At some primitive time in Europe’s emerging history, with the break-up of Roman patterns of lordship and great villa estates, landownership was a matter of armed dispute. There was, in effect, an age of robber barons: he who could establish himself by main force in a territory and hold it from a fortified residence against all comers, could expect with the passage of time, and by the concession of some one yet more strong than he, a king it might be or an emperor, to be recognized to own the property as of ‘right’. As a noble duke observed with aristocratic pleasantry in a television programme So Who Owns Britain while fishing a trout stream on his ancestral lands, ‘An Englishman’s castle is his home.’

Up to about AD 800, many ‘castle...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Plates

- Introduction - Siege Craft: The Basis of Medieval Warfare

- CHAPTER ONE - Fortified Towns and Cities

- CHAPTER TWO - Strong Points in a Landscape

- CHAPTER THREE - Castles and Fortifications: Designers, Builders and Developments

- CHAPTER FOUR - Machines of War

- CHAPTER FIVE - Fire Hazard

- CHAPTER SIX - Artillery

- CHAPTER SEVEN - Attack and Defence

- CHAPTER EIGHT - Logistics

- CHAPTER NINE - War Games, Psychology and Morale

- CHAPTER TEN - Women at War

- CHAPTER ELEVEN - Rules of Engagement

- CHAPTER TWELVE - The Horrors of Total War

- Appendix - Vegetius, the Medieval Textbook of Warfare

- Glossary of Technical Terms

- Notes on the Sources

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Medieval Siege and Siegecraft by Geoffrey Hindley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.