- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

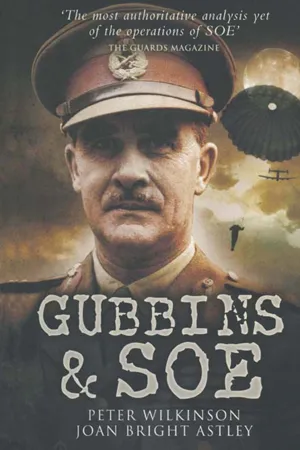

Gubbins & SOE

About this book

General Colin Gubbins was in charge of SOE during World War Two. This is the first biography of a man who was destined to live his life in the shadows. A biography of General Colin Gubbins, who was in charge of SOE during World War II. Gubbins was destined, by the nature of his profession, to live a secretive life, and the book, which incorporates much previously unpublished material, offers revelations about the man and his mysterious mission.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 The Family 1649–1902

2 The Schools 1902–1913

3 The Shop and The Great War 1913–1918

4 The Service Overseas: Archangel, Ireland, India, 1918–1930

5 The Nineteen-Thirties

6 The Polish Mission 1939

7 The MI(R) Mission in Paris 1939

8 The Norwegian Campaign 1940

9 The Auxiliary Units 1940

10 SOE: 1940/1941

11 SOE: 1942

12 SOE: 1943

13 SOE: 1943/1944

14 SOE: 1944

15 SOE: 1944/1945

16 Dissolution

17 Aftermath

Source Notes

Index

INTRODUCTION

There is little doubt that in the Second World War SOE’s influence was considerable both in exacerbating the ‘tension, battle and unrest’ endemic in most of the Occupied countries, but also, some would say, in eroding the limits of warfare still generally respected in 1939. However, there exists no satisfactory assessment of the contribution made by the Resistance to the Allied victory. Subjective estimates are numerous and vary considerably; moreover, in retrospect, things are apt to appear more orderly than they seemed at the time. However, most agree that in purely military terms resistance was of secondary importance and in no sense decisive. Nevertheless, it was not negligible: at one time the Balkan guerrillas contained more Axis divisions than the Allied armies in Italy, while guerrilla operations in North West Europe and South East Asia unquestionably facilitated the advance of the Allied armies which led ultimately to the enemy’s surrender. Nor is there agreement on the importance of the part played by SOE. Clearly, once the defeat of the Axis powers seemed certain and merely a matter of time, widespread insurgency in the Occupied countries was likely to develop. But to Gubbins it seemed no less certain that without outside coordination this valuable potential would be dissipated in clandestine activities of merely local significance. This view was shared by SHAEF and, in a report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff dated 18 July, 1945, General Eisenhower’s deputies, Generals Morgan and Bedell Smith, gave it as their considered judgment that ‘without the organization, communications, training and leadership which SOE supplied … resistance would have been of no military value.’ It is no coincidence that the features singled out were those to which Gubbins had given his personal attention. Indeed, it is at least arguable that without Gubbins’ professional guidance SOE might have gone the way of Section D.

Dr Dalton cherished the idea of a ‘Fourth Arm’ which would bring the enemy to its knees through subversion and propaganda, followed by a general rising of the working classes. Gubbins, on the other hand, was sceptical about what SOE and its agents could achieve on their own; he envisaged rather a paramilitary effort by indigenous resistance nourished and coordinated by SOE, acting not independently but under the operational direction of a theatre commander. It was a conception which involved transforming Baker Street from a civilian organization, geared primarily for sabotage, into a paramilitary headquarters with procedures compatible with those of regular troops. Nor was that all. In the early days SOE’s country sections had been responsible for enlisting their own agents; these were mainly volunteers with dual nationality or foreign expatriates living in the United Kingdom who, after individual training, were sent in to the field where they operated directly under the country sections’ orders. By mid-1941 the supply of these persons was dwindling, and was in any case inadequate for the large-scale operations which Gubbins had in mind. Nor was he convinced that their minor acts of sabotage, unless very carefully targeted, justified in military terms the appalling civilian reprisals which they occasioned. More and more Gubbins became convinced that, generally speaking, resistance to be effective needed to be on a scale which could only be achieved in cooperation with the Allied governments and representative committees now established in London, several of whom were in contact with, if not in control of, patriot elements in their respective countries. If they would provide the men, SOE would train them, arrange for their despatch to the field and handle their radio communications thereafter. Such an arrangement was clearly of mutual benefit, but Gubbins displayed considerable diplomatic skill in establishing the confidence required to bring it about. The Poles were no problem, for he already had many Polish friends including General Sikorski; and he soon established almost equally close relations with the Norwegians and the Dutch. Even the dour Czechs came to refer to him as ‘our Englishman’. The facilities which SOE had to offer, and the practical advice which he was able to give these Allied leaders, both formally and more often informally, gave Gubbins a unique standing in Allied circles which in turn aroused jealousy and criticism in Whitehall. Yet, looking back, Gubbins’ unpopularity in some military circles seems inexplicable. However, it was recognized by Lord Selborne in the following letter dated 17 October, 1945, which he wrote privately to the Secretary of State for War, recommending that Gubbins, when he relinquished his appointment as CD, should be made a substantive instead of merely a temporary major-general:

“I am aware that Gubbins is not universally popular in other departments, and I believe he has his critics in some parts of the War Office. About this I would only say that no Minister was served more loyally than I was by him, and that when a strong man is fighting to create a new organization which had to be carved out of the three services and other departments, it is not unnatural that he sometimes trod rather badly on people’s toes.”

From the moment they met in 1942 Selborne had trusted Gubbins absolutely, and there is ample evidence of his dependence on him, as indeed there is of the affection and respect which Gubbins had for Selborne. But Gubbins was loyal to his ministers as a matter of course, and he had been no less correct and, indeed, cordial with Dalton, who shared Selborne’s high regard for him.

On the whole Gubbins seems to have got on with ministers better than he got on with generals. The exception was Anthony Eden to whom he took a dislike on account of his condescending manner and his ruthless hostility to SOE; however, though he identified him with SOE, which he was determined to abolish, there is no reason to think that Eden disliked Gubbins personally; on the contrary, he respected his ability. Churchill, more tolerant than Eden of SOE, always had a good opinion of Gubbins who had caught his eye during the Norwegian campaign.* In the summer of 1940 he had shown a personal interest in Auxiliary Units, had approved of Gubbins’ subsequent secondment to SOE and, at Selborne’s instigation, intervened with the War Office on at least two occasions to prevent him being removed from Baker Street.

Gubbins’ most useful friend at court was General Ismay. Having frequently to deal with recalcitrant foreigners himself, Ismay realized what Gubbins was up against and also appreciated the valuable work that SOE was doing. Consequently he invariably found time to brief Gubbins regularly about strategic developments affecting SOE, and did his best to mitigate the frequent unhelpfulness of Whitehall departments which seemed to derive a special satisfaction from keeping SOE out in the cold. Only SOE’s protracted death throes in the summer and autumn of 1945 seemed to try the inexhaustible patience of this great man for whom Gubbins had the highest regard and whose support he particularly valued.

The attitude of General Brooke, the CIGS, was more equivocal than Ismay’s. Gubbins, who greatly respected him, had not only served under Brooke when the latter was Director of Military Training, but had briefly acted as his personal staff officer when Brooke was reorganizing the anti-aircraft defences immediately before the outbreak of war. They were members of the same regiment and knew each other well. Brooke was GOC Southern Command when Gubbins had returned from Norway hoping, if not for an active command, at least for a good training appointment. Although Brooke had not offered him either, he had shown considerable interest in Auxiliary Units and had as C-in-C Home Forces certainly opposed his transfer to SOE, possibly for Gubbins’ own good. Like most professional soldiers he disapproved of paramilitary organizations divorced from the Army.* When CIGS he showed little appreciation of SOE as an organization, though he was interested in individual members of the resistance groups, particularly Frenchmen, whom Gubbins arranged for him to see. At meetings of the Chiefs of Staff he was apt to show impatience with SOE’s affairs, and in 1946, when Gubbins’ appointment came to an end, Brooke seems to have made little effort to find him further employment.

Charles Hambro recognized that Gubbins was indispensable and immediately made him joint deputy with Hanbury-Williams, while continuing to treat him as an outstandingly competent general manager. Admittedly there were times when Gubbins would have endorsed Gladwyn Jebb’s opinion that “Hambro lived by bluff and charm” but they worked well together and remained good friends. There is no truth whatever in the rumour, fairly widespread at the time, that Gubbins used his influence with Selborne to secure Hambro’s dismissal; disloyalty of this sort was simply not in Gubbins’ nature.

When Gubbins succeeded Hambro as CD, his position in SOE was unchallenged, indeed it was unassailable. Although there remained a few conservative heads of section who genuinely deplored the paramilitary road which SOE had taken, their personal loyalty was beyond question. Resistance was a vocation for the young, not only in the field but also at headquarters, and to the younger members of his staff, both men and women, Gubbins was an authentic hero, possessing what E.M. Forster called the three heroic virtues: courage, generosity and compassion. Moreover, he was not only a natural leader of the young, but he shared with the great Duke of Marlborough “the power of commanding affection, while communicating energy”, enabling others to make use of abilities they had always possessed but had previously failed to recognize. With these exceptional powers of leadership Gubbins might, in other circumstances, have emerged from the war as a popular hero, but owing to the secrecy imposed on SOE and its activities he was, in his lifetime, virtually unknown in his own country. Abroad it was otherwise and he received high honours from many foreign governments.

However, wartime security was not the only reason why Gubbins received more acclaim abroad than at home. Britain was spared the shame and misery of enemy occupation; without this experience it is difficult to appreciate the part played by clandestine resistance both in restoring national self-respect and in permitting courageous individuals to escape from the ignominy of their situation. This spirit of resistance, which in many eyes Gubbins personified, is elusive in a mainly factual account of his achievements. However, it is not merely as the protagonist of a novel and controversial mode of warfare that he deserves to be remembered. It was as a resistance leader that he came to fashion SOE, and to write his own page in the history of almost every country occupied by the enemy in the Second World War.

* “An enterprising officer, Colonel Gubbins…” The Second World War, Vol 1, p. 510.

* See Brooke’s comments on Commandos in The Turn of the Tide, p. 245.

1

THE FAMILY 1649–1902

If asked, Colin Gubbins would say he was half Scottish and half English, his mother a McVean, his father born in India and raised and educated in England. But he could also claim Irish stock through an ancestor, Joseph (or George) Gubbins, a Captain of Dragoons who campaigned for Oliver Cromwell in Ireland, and decided in 1649 to acquire land and settle in County Limerick. The family prospered, married judiciously and became a county family of substance. There were no more soldiers in the family until 1775 when Colin’s great-grandfather, Joseph, was born; then there were no more soldiers until 1896 when Colin was born. As chance had it, the two of them were to share in a similar experience. In 1802 Joseph returned from service abroad and spent three years fortifying the southern counties of England against a threatened French invasion; in 1940, one hundred and thirty-eight years later, his great-grandson did much the same in command of a force raised to combat an invasion threat from Nazi Germany.

Joseph (1775–1832) married Charlotte Bathoe of Bath; he served in Santo Domingo with the South Hampshire Regiment, in Holland, Malta and Egypt with the 2nd Somersetshires and finally in 1810 he went to Nova Scotia as Inspecting Field Officer of Militia with the North American Force in New Brunswick. From Government House, Fredericton, the Governor’s wife, Lady Hunter, wrote on 2 October that:

“an addition of fourteen to our family… Colonel Gubbins, his wife, three children and nine servants … arrived here after being three months on board ship, and with not a place to put their heads on. Of course, we took them all in …. They have taken a house ten miles down the river, which will hold them all when put in repair, but that will be a work of time. Conceive fine, dashing characters, Bath people, quite the haut-ton, arriving knowing nothing of the country, with fine carriages, fine furniture etc. and where they are to be set down you could not drive a carriage fifty yards in any direction.”

However, on 14 December, she was writing that:

“our river is frozen fast, and become a post-road. The Gubbins … are quite new-fangled, and delighted with it, and come flying up here – ten miles – even to pay a morning visit, with a strong north-west wind and the glass below zero. Mrs Gubbins says she never saw anything so beautiful as the roads and the prospect of everything.”1

In 1816, aged forty, Joseph returned to England and retirement. His wife Charlotte died in 1824, and he, by now a major-general, died in 1832.

Their third son, Martin Richard (1812–1863), Colin’s grandfather, joined the Bengal Civil Service and later married Harriet Louisa, granddaughter of Sir Evan Nepean, Governor of Bombay. In 1856, a year before the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny, Martin was Financial Commissioner for Oudh Province. A...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Comments

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Gubbins & SOE by Joan Bright Astley,Peter Wilkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.