- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

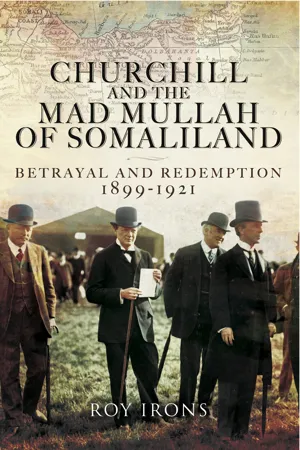

In the late nineteenth century, the British Empire commanded the seas and possessed a vast Indian Empire, as well as other extensive dominions in South East Asia, Australasia, America and Africa.To secure the trade route to the glittering riches of the orient, the port of Berbera in Somaliland was taken from the feeble grasp of an Egyptian monarch, and to secure that port, treaties were concluded with the fierce and warlike nomad tribes who roamed the inhospitable wastes of the hinterland, unequivocally granting them 'the gracious favour and protection of the Queen'. But there arose in that wilderness a man of deep and unalterable convictions; the Sayyid, the 'Mad Mullah', who utilised his great poetic and oratorical gifts with merciless and unrelenting fury to convince his fellow nomads to follow him in an anti- Christian and anti-colonial crusade. At great expense, four Imperial expeditions were sent to crush him and to support his terrified opponents; four times the military genius of the Sayyid eluded them.It was at this point that the rising voice of Winston Churchill convinced his Liberal colleagues to abandon the expensive contest and retreat to the coast. By this betrayal, one third of the British 'protected' population perished.It wasn't until after the Great War that Churchill, now Minister for both War and Air, as well as a major influence in the rise of Air Power, was able to redeem this betrayal. The part he played in the destruction of the Sayyid's temporal power at this point was substantial, and the preservation of the Royal Air Force was also secured. By unleashing Sir Hugh Trenchard and giving his blessing to a lightning campaign, his original betrayal was considered to be redeemed in part and his honour belatedly and inexpensively restored.In this enthralling volume, Roy Irons brings to life this period of dynamic unrest, drawing together a number of historical accounts of the time as well as an evocative selection of illustrative materials, including maps and portraits of the main players at the forefront of the action. Personalities such as Carton de Wiart, Lord Ismay, and the much decorated Sir John 'Johnny' Gough, VC, KCB, CHG feature, as do the vaunted Camel Corps, in this eminently well-researched narrative account of this eventful and controversial episode of world history.As featured in Essence Magazine.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland by Roy Irons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del siglo XIX. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Somalis

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Thomas Gray, ‘Elegy written in a country churchyard’

Of all the blessings which nature, or a beneficent God, could bestow upon a people, none could be greater than a rich soil, a plentiful supply of water in due season, and an equable and moderate climate. An autumn field bright with golden wheat, sunshine and clouds reflected from sparkling and murmuring streams rich with fish, trees laden with fruit or wood for winter fuel, fat cattle, pigs and sheep in woods or pastures washed by a regular and refreshing rainfall, are in most religions the attributes of Heaven, the land of God and of the select few. Such lands are conducive to strong and stable states, where a leisured aristocracy might maintain an ordered rule, an unchanging culture and a long peace, until they are overthrown by the envy of war-sharpened warrior invaders or by their own plebeian toilers, or reinvigorated by those whose minds are sharpened by a thriving trade or an innovative and profitable industry.

The land of the Somalis has neither regular water nor many large areas of rich soils. Sometimes great swathes of this terrible land are subjected to devastating droughts, and have no water at all. In many places, where hyaenas haunt the scrub, where leopards leap over the thornbush zariba to take sheep or children, where lions prowl in the darkness, or where the sun shines fiercely over a desert, and mirages of camel trains led by white clad figures stalk the skies, it might be described as close to a hell. At the beginning of the twentieth century the land had little surplus to enable many to develop a large capital from trade with happier lands. Sheep, oxen, goats and hides were exchanged for rice, dates, cotton, rifles and ammunition and quat, a mild intoxicant. Its greatest resource for its human inhabitants is the camel, which enables them to travel with their sheep and cattle from an arid location to another which has been temporarily blessed with a seasonal, and unreliable, rainfall, before the burning and pitiless sun sucks the life-giving water from the land.

The land occupied by the Somalis, in the ‘Horn of Africa’, is some 320,000 square miles in extent, and is bordered by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, the Indian Ocean, the Kenyan border and Ethiopia. Of this land, the British Protectorate, comprising some 60,000 square miles, lay in the north, along the Gulf of Aden (although the strip of the Somalis’ land along the Kenyan border was included by the British in their East African Protectorate, and has been inherited by Kenya). Its principal town was the port of Berbera. The Italian Protectorate ran from the Gulf of Aden down to the Kenyan border, while a vast area of western Somaliland, inhabited by the Ogaden tribes, was (and still is) occupied by the Ethiopians (Abyssinians). A smaller French enclave in the north centred around the port of Djibouti.

Somaliland is divided geographically into three broad areas. The first, the coastal plain, lies between the sea and the mountains. Its width varies from some sixty miles at the ancient city of Zeyla near the border with French Somaliland to a few hundred yards. It is arid. Sandstorms scour the few thorn bushes which form almost the only vegetation. Here ‘All the world seems ablaze’, wrote Douglas Jardine, ‘and it is seldom that a cloud obstructs the pitiless sun’.1 The great nineteenth century explorer Sir Richard Burton, who visited the land in 1854, described it as ‘A low glaring flat of yellow sand, desert and heat – reeking’. ‘The Somal themselves’, wrote Burton, ‘described it as the Barr el Ajam, or Barbarian land (i.e. Land not Arab).2

The second broad area of Somaliland comprises the Maritime Mountains. The foothills of the mountains are described by Jardine as equally inhospitable, being known in Somali as the ‘Guban’ – the burnt. Harsh boulders strew the beds of rivers of sand, although a coarse grass grows. The mountains themselves rise to some four or six thousand feet above sea level, and in the more pleasant climate grass, gum trees, myrrh, acacias and giant euphorbia, and in places even fig trees flourish. Life-giving water lies in rocky pools.3

The third tract is a plateau, which slopes from north to south, from six thousand feet to the valley of the river Shabeelle4 which, eventually unequal to its long contest with the sun, expires in a saltmarsh before reaching the sea. The plateau itself is far from a continuous desert, but contains a very large variety of landscapes, from hills and mountains to open meadowland, very dense bush, and closely intersected country. The common feature is lack of water, at least in the dry season, and sometimes all year.

The culture, the ‘software’ of the Somali people, has been formed by this harsh and demanding environment, and by interaction with other cultures, and this has been influenced by the ‘hardware’ of the Somali people, their genetic makeup. This latter, of course, will always vary more than the software, which can be almost identical in many, i.e. the nomad mores and the Muslim faith. An individual may vary quite sharply from a general description of his ‘race’, for genetic admixture will ensure that a ‘tall’ people will have some short representatives, and an ‘intelligent’ people many stupid ones. Two people may be culturally, but never (unless identical twins) genetically identical. With these caveats in mind, it may be broadly stated that the Somali people originated from regions to the north, from Arabia, North Africa and Upper Egypt, with some further genetic input from Europe. Sometime after the birth of Islam, perhaps around the tenth century AD, the semi-legendary Arab Sheikh Isma’il Jabarti, intermarrying with the Somalis, founded the Darod clan family, and perhaps two centuries later, the Arab Sheikh Isaq similarly founded the Isaaq clans. Both slowly pushed south to their present position, displacing the Oromos.5 The Somalis also seem to have a small input of negro/Bantu genes, perhaps 10 per cent; although negroes (along with almost all other peoples!) seem to have been despised. The language is Cushitic, and is related (as are, of course, the Somalis themselves) to Arabic, and to that of the detested Gallas, although ‘Galla’, unbeliever, is itself a derogatory term for the Oromo and Borana of Ethiopia and Northern Kenya.6

The Somali language is an enormously powerful vehicle of oratory, exhortation, persuasion and poetry. Sir Richard Burton, a brilliant linguist, noted the paradoxical combination of illiteracy and what might be described as a flourishing ‘oral literature’. ‘It is strange’, he observed, ‘that a dialect which has no written character should so abound in poetry and eloquence’.

There are thousands of songs, some local, others general, upon all conceivable subjects, such as camel loading, drawing water, and elephant hunting; every man of education knows a variety of them…The country teems with ‘poets, poetasters, poetitoes and poetaccios:’ every man has his recognised position in literature as accurately defined as though he had been reviewed in a century of magazines, – the fine ear of this people causing them to take the greatest pleasure in harmonious sounds and poetical expressions, whereas a false quantity or a prosaic phrase excite their violent indignation… Every chief in the country must have a panegyric to be sung by his clan, and the great patronise light literature by keeping a poet. The amatory is of course the favourite theme…The subjects are frequently pastoral: the lover for instance invites his mistress to walk with him towards the well in Lahelo, the Arcadia of the land; he compares her legs to the tall straight Libi tree, and imprecates the direst curses on her head if she refuse to drink with him the milk of his favourite camel…Sometimes a black Tyrtaeus7 breaks into a wild lament for the loss of warriors or territory: he taunts the clan with cowardice, reminds them of their slain kindred, better men than themselves, whose spirits cannot rest unavenged in their gory graves, and urges a furious onslaught upon the exulting victor.

A little later, another intrepid geographer, Harald Swayne, wrote that the typically ‘wonderfully bright and intelligent’ Somali had:

…a great deal of romance in his composition, and in his natural nomad state, on the long, lazy days, when there is no looting to be done, while his women and children are away minding his flocks, he takes his praying – mat and water bottle, and sits a hundred yards from his karia8 under a flat, shady guda tree, lazily droning out melancholy-sounding chants on the themes of his dusky loves, looted or otherwise; on the often miserable screw which he calls faras, the horse; and on the supreme pleasure of eating stolen camels.9

He also noted that ‘There is no social system, but patriarchal government by tribes, clans, and families; no cohesion, and no paramount native authority; and the whole country has been from time immemorial in a chronic state of petty warfare and blood feuds’.

All the sources from the turn of the twentieth century and before agree on the high intelligence of the Somali people; yet to what purpose could such high intelligence and ability be put in the endlessly repeated nomadic journeying of the people of the plateau? Well, it seems from the above that the first call on the brains of the Somali people after the considerable requirements of exacting a living from their demanding land was language; not only the plain meaning of their communications, but innuendoes, poetic scansion, the enormously complicated alliteration, each word being weighed in a scale of reason, of form, of rhythm, of allusion. Their campfires and assemblies were the battlegrounds of a thousand Shakespeares, with well-aimed words in the place of spears, and oratorical contests in the place of an Homeric single combat. Nor were the battling heroes confined to the living; the words of long dead orators and poets would once again rise up in support or opposition to a proposal – although heavy was the social disgrace of a man who endeavoured to claim their words as his own, in a society where literary memories were long and almost incredibly accurate.10

One such oratorical contest, in more modern times, is described by Said S Samatar, a Professor of History at Rutgers University and former Somali pastoralist. He describes an incident between the Daaquato and Beerato clans in the Ogaden in 1962–3.11 The Daaquato were a nomad clan, the Beerato were agriculturalists. In an incident reminiscent of a Hollywood ‘western’, the Beerato had cultivated fields in the lower Shabeele (Leopard) river, which the Daaquato still considered to be grazing land. A Beerato maize field was grazed by Daaquato cattle and camels; accusations flew and two Beerato and a Daaquato were killed in the ensuing melee. For the next three months the town of Quallafo was stained with the blood of the elders and leaders of both clans, while the Ethiopians who ruled the Ogaden looked on with indifference. But the Beerato farmers made a near fatal error; not content with a desultory warfare of mutual murder and ambush, they held a war dance, and celebrated the murder of a Daaquato notable in poetry. This was too much for the Daaquato youth, who were narrowly prevented by their elders from a general slaughter of the Beerato, who would not have been able to contain the nomads in an all-out war. Indeed, Professor Samatar records that in a war thirty years before, the Daaquato had obliged the Beerato peace delegates to hold shoes in their mouths as a mark of submission.

The Daaquato now held a clan meeting to decide the fate of the Beerato. These assemblies were open to all, and generally took place under the shade of a tree. All could participate, although in practice these assemblies were dominated by experts in tradition, orators and poets. In this vital meeting, two orator-poets held the floor. The voice for war and revenge in the name of God was almost triumphant – the young men shouted and arose to ride off to the slaughter, and the fate of the Beerato seemed sealed – when the second voice was heard reminding the assembly that fellow Muslims could hardly be slaughtered in the name of God. Peace talks were held, and the price of the shedding of nomad blood was settled at five hundred Beerato cattle and a ‘substantial quantity’ of grain.

This incident, although it took place some sixty years after the events to be related, shows the democratic nature of the assemblies of the nomad tribes, the tribal feuds and hostilities and raiding that seemed to form an essential part of the nomad existence, and the two great influences on the minds of the Somali nomad – poetry and Islam.

The religion enshrined in the Koran was revealed to the Prophet Mohammed alone, who, beginning with his wife Khadijah, his cousin Ali, his servant Yazid and his friend Abubekr, gradually convinced an ever-growing circle of its truth. The ruling tribe of Mecca (of whom he was one) becoming alarmed at this threat to their lucrative control of the shrine centred on the Kaaba (a black meteoritic stone that had been sacred to the surrounding Arab tribes for centuries), and fearful of disorder, sought to end the religion of Islam by the murder of its Prophet. Forewarned, Mohammed fled to the sanctuary offered by the divided city of Medina, where he had many converts (the Ansar, or helpers), who submitted to his unifying rule, and the year of his flight (the Hegira, 622 AD) began the Islamic era.12 After a successful defence of Medina against the Meccans, and having taken a heavy toll of the caravans sent by the Meccans towards Syria and the east, the rulers of that important city, undermined by conversions to the Muslim faith and by military defeat, belatedly acknowledged the truth of the Koran and the rule of the Prophet. Before his death in 632 AD at Medina, which had become the capital city of Islam, the genius of Mohammed had united Arabia under his religion and rule. Few events in the history of man can be as remarkable or as significant.

The successors to Mohammed’s temporal rule, the caliphs, began the conquest of Syria and Egypt from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine), and Iraq from the Sassanid Persian empires, enfeebled as they were from a long, bitter, destructive and costly war. After the murder of Othman, the third caliph, Ali, the cousin of the Prophet and later his son-in-law, succeeded to the caliphate (he had perhaps expected to be the first caliph) but tensions had arisen between the early Meccan believers, the Ansar of Medina and the more tardy rulers of Mecca who were late comers to the religion, but experienced politicians; and it was claimed that the murderers of Othman were not pursued with vigour by his successor. A civil war ensued, the saintly Ali was murdered, and the successive murders of his lineal descendants, who formed the ‘twelve Imams’,13 eventually produced a bitter schism in the heart of Islam. Ali’s followers were labelled the Shia, or party, of Ali, or his sectaries, by the orthodox, the Sunnis. This often embittered division of Islam still persists.

During the Hegira some of Mohammed’s followers had fled to Abyssinia (Ethiopia) where they received sanctuary from its Christian rulers. This (very temporary) good feeling between the religions might have been expected by an optimist, since Mohammed had regarded Jesus as the second greatest of the Prophets. Mohammed regarded the believers of Christianity and Judaism as ‘people of the book’, the Old Testament being revered by Islam and Christianity alike. But to the rulers of mankind, of whatever religious or philosophic persuasion, neighbouring nations more often become sources of aggrandizement rather than alliance, and are more often rivals than friends. The Muslim conquest of the Middle and Near East isolated Abyssinia from the rest of Christendom and it became an island in an Islamic sea. That hostility, which persists to this day, lies at the very centre of the events related here.

The details of the Muslim penetration of Somalia and the events leading to the conversion of the whole country are largely unknown. However, the close trading relationship between the Somalis and Arabs, their cultural and linguistic affinities and the short sea voyage between south Arabia and the Horn of Africa must have ensured that the conversion was early, and the proud attribution of Somali tribal ancestry to the descendants of the Prophet speak of a considerable immigration of Arabs, and of their high status. Indeed, in 1974 Somalia became a member of the Arab League.14 It is maintained by some that the poetical beauty of the Arabic in which the Koran was written is proof of its divinity; this beauty would have certainly rung true in a Somalian ear.

The Somalis are divided ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Maps

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 The Somalis

- Chapter 2 The European World Supremacy and the Coming of the British Protectorate

- Chapter 3 War with the Sayyid – The First Expedition

- Chapter 4 With the Abyssinians

- Chapter 5 War with the Sayyid – The Second Expedition

- Chapter 6 War with the Sayyid – The Third Expedition

- Chapter 7 War with the Sayyid – The Fourth Expedition

- Chapter 8 Enter the Giant

- Chapter 9 The Triumph of the Giant

- Chapter 10 The War Renewed and the Battle of Dul Madoba

- Chapter 11 Birth and Re-birth: The Flying Corps and the Camel Corps

- Chapter 12 Deus Ex Machina

- Chapter 13 The End of the Sayyid

- Chapter 14 Retrospect

- Selected Bibliography

- Notes