- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

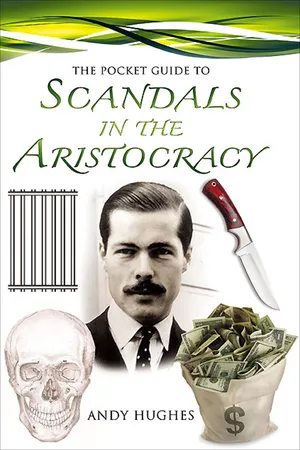

The Pocket Guide to Scandals in the Aristocracy

About this book

We were going to call this a Pocket Guide to Noble Scandals but theres nothing noble about these aristocrats. Tales of greed, list, murder and mayhem litter the pages of Andy Hughes must-read book. Whether its gambling away their familys fortune, writing racy poems and shocking decent people, the aristocracy have been at the center of scandals for centuries, abusing their position of power to take advantage of everyone else or kill those who get in their way. This Pocket Guide to Scandals in the Aristocracy is a race through history, divided into eras to introduce the best and worst scurrilous tales from Francis Lovell being bricked up alive in his stately home to the ongoing mystery of Lord Lucan and delicious (but true) gossip which delighted readers when the aristocrats were thinly disguised in the novels of their day. Bring history alive with this fact-filled guide.Youll also love: The Pocket Guide to Royal Scandals and The Pocket Guide to Political Scandals, both by Andy Hughes

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Setting the Scene

Britain has nearly always had some sort of class system, a pecking order or a social hierarchy, of one kind or another. The British aristocracy is hundreds of years old, and some would argue, part of the cause of a class-ridden society. Others would say it helps make up our richly endowed social spectrum. Do we need a noble class in this day and age? Are they really superior to us, and if so, in what way? First of all, before we look at scandals in the aristocracy throughout the ages, let us look at what exactly the aristocracy is. The word actually comes from the Greek ‘aristos’ and ‘kratos’, literally meaning ‘rule by the best’. Other modern day dictionary definitions of aristocracy include one or more of the following terms:

- Government by ruling class

- A class of people superior to others

- Noble birth

- Upper class

- High birth

- Privileged

- Socially, economically or intellectually superior

- Powerful members of society

- Those in the highest places of the social hierarchy

- Landowning gentry

If you look back throughout history, both in Britain and in other countries, you can see real evidence that power and strength often came from wealthy, landowning and titled aristocrats. However, the scale of Britain’s middle class has dramatically increased over the generations. Put simply, the balance of power has gradually moved from royalty, to nobility, to democracy, with a democratically elected parliament, and eventually a middle-class section of society with the vote, after the Reform Act of 1832, plus later reforms. Some women got the vote in 1918, and more in 1928.

Aristocrats may not be our social and political betters any more, but for many of them their wealth and longstanding genealogical background provides them with a secure standing in the social pecking order. Britain’s social history has varied between three main structures; hierarchical, triadic and dichotomous. A hierarchical society is organised into several levels and structural layers, laid out according to certain rules, criteria and tradition. Triadic is simpler; with an upper, middle and lower class. Dichotomous is a simple ‘them up there’ versus ‘us down here’ society, or a division into two easily recognised different parts. In other words, the patricians looking down on the peasants. A patrician is simply classed as one of refined and noble origin. David Cannadine argues, in Class in Britain, that the vagueness of these three models has allowed Britain to put up with them for so long and alternate from one to the other. I would agree that the lines can be crossed and rather blurred. Is society and social class so two-dimensional and like a ladder, or it is more complex, like a revolving tree, three-dimensional and with depth?

Former British Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair, in office 1997–2007, ended the right of some hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords and help govern the country from their unelected seat. One can argue the lines of class have become blurred throughout the last two or three generations. Hundreds of years ago, most people knew who they were and accepted their lot. We are more ambitious now and have better opportunities in much of the developed world. Do East End working-class boys and big achievers like Alan Sugar, later ‘Sir’ Alan Sugar and then ‘Lord’ Sugar, turn from working class to upper class? Here is another example. In the 1950s and 1960s my grandfather was a proud ‘working-class’ man. Ernie Rowan always voted Labour, and did not like the ‘posh people with titles’. But his social lines were definitely blurred; he loved the Queen for starters, and despite frequenting the working men’s clubs of York, worked hard, saved harder and by the 1970s lived in one of the most exclusive ‘posh’ parts of York. To refer to him as a middle-class man would have been a real insult to his values. In other words, can you choose your class? Can you earn it? Can you be given it? Can you change it? Therefore, who exactly is an aristocrat and why? For example, what makes Earl Spencer an aristocrat? Is it the title bestowed upon his family, or the immense wealth that generations of the family earned and built on, or is it both? If the Earl gave it all up and went to work in a burger bar, but kept a five-bedroom house, would he be working class, middle class, or still a noble aristocrat?

The aristocracy has faced its fair share of troubles throughout the years. In Europe, the First and Second World Wars and the Russian Revolution helped spread communism and weaken the aristocracy throughout the continent. The situation came full circle in places though. After the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, some European aristocrats even had their confiscated property and land restored to them. They have survived wars, depressions and family splits, to hang on to immense wealth in most cases. Britain’s own aristocracy has had both good and bad times throughout history. It was a straightforward existence in the times of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, through the 1700s and into the Victorian age. But everything from the Civil War and republicanism, to plagues and economic troubles has hit the top echelons of society, not to mention divorce, death duties and incompetence. The responsibilities of the aristocracy have always been to hold on to their lands and titles, marry into other good families and pass on as much as possible. Some have failed over the years, selling the family silver and losing money and land along the way. Many aristocrats sold land and property after the First World War, and today’s aristocracy is a mere slimmed down version. It no longer has the amount of pomp, power and glamour of yesteryear. Another reason for the slimming down of the wealth and power of Britain’s aristocracy is the change in agricultural patterns since the late nineteenth century. We did not rely on the grain from the lands of various lords so much anymore. Imports of various foods, fresh and refrigerated, from Europe and America, reduced the dependency on our own land. This development in the fashion of commerce hit the British landowners and the farmers where it hurt, and it was a long term change. This is one of the reasons, I would argue, that so many aristocrats have opened their homes to the public, for a fee, or sold off some of their possessions. Lords were also stung by higher taxes, and death duties hit many of them especially hard.

As the twentieth century progressed, the trend of divorce and settlement also hit the aristocracy, either by direct cost or, in my view, the all too often spendthrift practices of second wives in awe of titles and wealth; spending money like it was going out of fashion. Modern day aristocrats can witness spendthrift family members and wives, and still have to give half of what’s left in a divorce several years later. This would never have happened in the 1700s. However, if many British aristocratic titles date back to feudal times, can there be new aristocrats? If money, power, land and titles are the only recipe for being an aristocrat, one could suggest other names as being noble aristocrats. Here one could include Ted Turner, former CNN owner and purchaser of hundreds of thousands of acres of land. Sir Richard Branson runs one of Britain’s biggest businesses and has a title. Is a newly created Sir, a Lord or Dame an aristocrat, or does it depend on their wealth, power and possessions? John Luckas, the American historian, asks if distinction comes from public service or from blood, are they noble because they are powerful or powerful because they are noble? Peregrine Worsthorne says in Democracy Needs Aristocracy that families who have served the nation for generations, become part of the country’s history and mythology.

What has the aristocracy actually ever done for us? Some see them as custodians of our lands, guardians of the countryside and hereditary custodians of Britain’s impressive manors, stately homes and estates. Jamie Douglas-Home, author of Stately Passions: The Scandals of Britain’s Great House, comments on the generations of the aristocracy acting as ‘custodians of great houses and estates’. He states that it is their duty to keep them in tact for future generations to enjoy. He is amazed by the actions of some aristocrats who gamble away their inheritance, produce illegitimate children and basically live a drug and drink-fuelled existence, with little care or regard for the historical consequences. Obviously this has not been the case with all aristocrats, just some of them. One could also call it easy come, easy go. He calls it a privileged and spoilt, bed-hopping existence, and asks if a drug, drink and over-sexed life is true in all levels of society, or just royalty and aristocracy. I would argue that if many of the irresponsible aristocrats had to actually work for a living and worry about paying bills and rent, then they would have less time to play around with the chambermaids and sit around taking drugs, getting drunk and producing offspring. Instead, they don’t have the same social pressures, and never have, so they can use that ‘extra’ time, to cause mischief, even with their own possessions, relationships, inheritance and position. Is Jamie Douglas-Home making it clear that some aristocrats, past and present, have indeed neglected some of their duties? Rather than take part in the daily 9–5 grind, all one has to do as an aristocrat is preserve your own little bit of history. Many of them have failed to do that, selling off the family silver to raise money. It’s not like the aristocrats from the Middle Ages who had several duties in helping to run the country and keep the peace, or those of the 1700s and 1800s packing Parliament. Those aristocrats of the 1900s and beyond have had less to do than all of their antecedents. One can argue that aristocrats are the architects of their own very slow demise, indicated by those selling off the family homes and possessions. Ivan Lindsay’s article ‘When the Going gets Toff’ in Spears WMS magazine, No. 17, says, ‘The aristocracy has faded from public life … living on the edge of extinction … custodians of their shrinking share of the national heritage.’ Traditional aristocrats in Britain see themselves as custodian of their lands, with the family belonging to the possessions, rather than the other way round.

In my earlier pontificating about one changing social class, one has to consider the case of the wealthy woman who bought Fawley Court. We should also consider her attitude to her position. In April 2010, this wealthy divorcee, undoubtedly upper class, bought the property in Henley-on-Thames. She spent £22 million on the mansion and its 62 surrounding acres. William of Orange stayed at the mansion during the early days of the Glorious Revolution in 1688. She told the local newspaper the Henley Standard that she did not consider herself as the owner of the estate, just lucky to be its gatekeeper. This is a typical aristocratic attitude that it is not theirs, but they are looking after it for the nation. Critics would claim that is a lame excuse for hanging on to millions of pounds worth of treasures and possessions. But why isn’t she now considered an aristocrat, if one dictionary definition, ‘economically superior’, is considered correct?

Meanwhile, social commentators on the left of the political spectrum might argue that Britain’s aristocracy is old fashioned and sexist, with a strict adherence to the rule of primogeniture, with sons always the most important and taking priority for inheritance of lands and titles. Most English titles have gone to the oldest male heir, usually, but not always, a direct son. Disentailment sometimes took place to avoid passing on both title and money as well, if the heir was unsuitable, perhaps mad or irresponsible.

During the Second World War some aristocrats were used as weapons. Certain titled people were selected to spread false information at social gatherings and parties. The misleading gossip was supposed to make its way to German spies who were mixing socially at all levels of society. It was hoped that they would pass on false information to Berlin and waste the time and money of the Third Reich’s military. The scheme was managed by an organisation called the London Controlling Section. Secret files confirming the plans were released by the National Archives in 2008. Whether Britain’s aristocracy will survive another few hundred years is debateable. Whether the scandalous behaviour, by some, perpetuates that downfall is very doubtful. But with so much money and time on their hands, it’s a recipe for mischief, misbehaviour and scandal for some aristocrats. Some act with great dignity and responsibility. Timo Airaksinen wrote in Homo Oeconomicus that scandals do not exist anymore because people just don’t care. He argues that scandals are only scandals if virtues and values are broken. He wants us to understand the difference between scandal and sensation. This book aims to expose and remind us peasants of the sometimes shocking behaviour and sanctimonious attitude of our most noble citizens, past and present. It is the aim of this book, The Pocket Guide to Scandals of the Aristocracy, to name and shame the naughty nobles. In fact, whilst some are loyal, noble, upstanding citizens, others are greedy, lazy, arrogant, overweight, overfed and work-shy.

Some titles classed as Aristocracy

- Emperor/Empress

- King/Queen

- Prince/Princess

- Duke/Duchess

- Maharajah (India, Nepal, meaning ‘highest king’)

- Kaiser (a German emperor)

- Shah (an Iranian emperor)

- Khan (a Central Asian emperor)

- Sultan (Ottoman title for a ruler of a sultanate)

- Archduke (ruler of a the former archduchy of Austria)

- Grand Duke (ruler of a grand duchy)

- Elector/Electress (German)

- Marquess/Marchioness

- Count/Countess

- Viscount

- Freiherr

- Baron/Baroness

- Baronet/Baronetess

- Jonkher (a new type of honourable Dutch title)

- Knight

- Dame

- Vidame

- Fidalgo

Opponents of the idea of a land-owning gentry are quick to point out how the titled of the country own too much of it. It’s not only staunch socialists who criticise the aristocracy for holding on to too much acreage, but many realists, builders, planners and those without land are often unhappy with the situation too. In 1934 in the United States, Louisiana Senator Huey P. Long (the Kingfish) had been speaking out against the president of the day, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and his New Deal policies to help the country get out of the Great Depression. Long created the ‘Share Our Wealth’ programme and stirred up anti-capitalist sentiment by publicly declaring how unfair it was that a tiny percentage of the American population owned most of the nation’s land, and how many were left with nothing. These comments came even though there was no aristocracy as such in America. Could the financially superior in the United States have been classed as their own aristocracy? In short, it proves people can be jealous of what others have got, regardless of their social class or lack of it.

Back in Britain, in the twenty-first century, there is a real shortage of land and not enough space to build new homes. Hundreds of thousands of people are officially homeless at any one time. Many live in hostels or bed and breakfast establishments at the expense of a local authority. It was worse in the Great Depression in the United States in the late 1920s and early 1930s, where millions were out of work and lived in Hoovervilles. These were makeshift and home-made tents set up in dirty camps without sanitation or power of any kind. Most blamed the recession completely on President Hoover, and that’s how these camps got their names. In Britain, land is expensive, at a premium, and well sought after. Many hardworking people simply cannot afford to buy a small flat or house, or a tiny piece of land. Part of the reason, one could argue, is that our beloved aristocracy and their families, about six thousand of them, own sixty-nine per cent of Britain’s land. A growing ‘common’ population is being squeezed into smaller pockets of land all the time, at a higher and higher cost to the average working family. Of course, regular landlords and investors with two or more houses are partly to blame, but one can argue that the aristocracy should bear the brunt of it. Some of them even get huge European Union subsidies to keep their agricultural lands empty, fallow and unproductive. The Duke of Westminster, Duke of Northumberland, Duchy of Cornwall, Duke of Buccleuch and the estate of the Atholl Dukedom are some of the biggest landowners in the country. Together they hold 800,000 acres. Dwarfing these wealthy people, the Government (mainly the MOD), the Forestry Commission and the Crown Estates add up to many more times that of the landed gentry. In short, between the Crown, the aristocracy and the Government, there is precious little left over for the common man.

It is a slow turnaround in history too because many of the country’s biggest landowners, the noble class, have had their lands since the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, and have no intention of letting them go. In 1873, Return of Owners Land was published, and detailed who owned what in the country. It showed ninety-six per cent of people owned nothing at all. At least today, millions o...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Byline

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Setting the Scene

- Chapter 2 The Main Big Scandals

- Chapter 3 The Nobles, their Responsibilities and Work

- Chapter 4 The Stately Homes

- Chapter 5 The House of Lords

- Chapter 6 And Finally

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Pocket Guide to Scandals in the Aristocracy by Andy K. Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia militar y marítima. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.