eBook - ePub

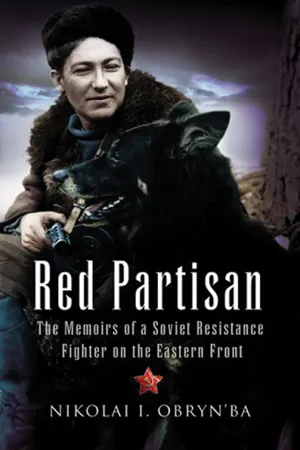

Red Partisan

The Memoirs of a Soviet Resistance Fighter on the Eastern Front

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A memoir of a Soviet artist who became a resistance fighter against Nazi Germany during World War II.

The epic World War II battles between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union are the subject of a vast literature, but little has been published in English on the experiences of ordinary Soviets?civilians and soldiers?who were sucked into a bitter conflict that marked their lives forever. Their struggle for survival, and their resistance to the invaders' brutality in the occupied territories, is one of the great untold stories of the war.

Written late in the author's life, Nikolai Obryn'ba's unforgettable, intimate memoir tells of Operation Barbarossa, during which he was taken prisoner; the horrors of SS prison camps; his escape; his war fighting behind German lines as a partisan; and the world of suffering and tragedy around him. His perceptive, uncompromising account lays bare the everyday reality of war on the Eastern Front.

Praise for Red Partisan

"[Obryn'ba's] descriptions of life in a German POW camp offer unique insights into a little-discussed aspect of the Eastern Front." — Military Review

"Obryn'ba's simple and candid yet gripping memoir presents a credible mosaic of vivid images of life in the Red Army during the harrowing first few months of war and unprecedented details about his participation in the brutal but shadowy partisan war that raged deep in the German army's rear. A must read for those seeking a human face on this most inhuman of twentieth-century wars." —David M. Glantz, historian of the Soviet military

The epic World War II battles between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union are the subject of a vast literature, but little has been published in English on the experiences of ordinary Soviets?civilians and soldiers?who were sucked into a bitter conflict that marked their lives forever. Their struggle for survival, and their resistance to the invaders' brutality in the occupied territories, is one of the great untold stories of the war.

Written late in the author's life, Nikolai Obryn'ba's unforgettable, intimate memoir tells of Operation Barbarossa, during which he was taken prisoner; the horrors of SS prison camps; his escape; his war fighting behind German lines as a partisan; and the world of suffering and tragedy around him. His perceptive, uncompromising account lays bare the everyday reality of war on the Eastern Front.

Praise for Red Partisan

"[Obryn'ba's] descriptions of life in a German POW camp offer unique insights into a little-discussed aspect of the Eastern Front." — Military Review

"Obryn'ba's simple and candid yet gripping memoir presents a credible mosaic of vivid images of life in the Red Army during the harrowing first few months of war and unprecedented details about his participation in the brutal but shadowy partisan war that raged deep in the German army's rear. A must read for those seeking a human face on this most inhuman of twentieth-century wars." —David M. Glantz, historian of the Soviet military

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Red Partisan by Nikolai I. Obryn'ba in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Captivity

CHAPTER ONE

First Night of the War

For many Muscovites, 22 June 1941 will forever stand out as the most memorable day of their lives. Suddenly, one sunny morning, the announcement of war burst into our lives, wrecking fates and shattering dreams, hopes and expectations. The day was bright and sunny. My wife and I were going for a holiday to the Dniepr. I had been chopping wood in the yard since morning and discussing with the neighbours what kind of camera would be best for photographing landscapes. Suddenly a boy ran into the yard: ‘Uncle Kolya, the wireless says the war’s started!’ Everyone rushed to the loudspeakers: ‘Today without any declaration of war ...’ From this moment our lives changed. From this moment we all faced the question of ‘tomorrow’ and our place in the war.

Galochka ran up, out of breath: ‘I couldn’t get through! There were vehicles with soldiers on the road. One threw me a letter and yelled, ‘‘get it to a post office!” Then another one, and another one! They started throwing down envelopes from all the vehicles. I didn’t have time to catch them all – they were falling and everyone was picking them up.’

We had to get ready, to stock up on food. We rushed to the shops. People were running about, buying all that was available. None of it was left for us – only sets of mixed pastries. We bought five boxes and returned home.

I set about ringing the guys and we decided to go to the Revolution Museum. I was friends with some people from Kiev, with whom I had transferred to the Moscow Arts Institute. They were: Leva Naroditsky, Nikolai Peredny and Boris Kerstens. We had all finished Year Five and ‘reached the diploma,’ as the saying was then. I had studied in the battle painting class, run by Petr Dmitrievich Pokarzhevsky and worked with him on the panorama, ‘The Defence of Tsaritsyn’ [an episode from the Russian Civil War – Trans.]. All four of us had been working in the Revolution Museum, making copies of pictures and some pieces for the exposition, so we went to the museum to join in the work for the front.

Everything was in turmoil. Everyone was in a hurry. Yet complete strangers were stopping each other in the street, striking up conversations about the same thing: the war. In the museum we were told to make posters on the following themes: ‘All for the front!’ ‘Have you volunteered?!’ and ‘Productive work will help the front!’ I started drawing a picture for the museum exposition, entitled: ‘The German Occupiers in the Ukraine in 1918’.

When I came home in the evening I told Galochka that we had already got jobs. My mother-in-law was at home with the kids. We began to make blackout sheets and stick up the windows with criss-crossing bands of paper. But we couldn’t stay at home for long. We longed to see people, so we ran to Sretenka, to a movie-theatre. Having spent about fifteen minutes there, we suddenly realized our four-year-old son, Igor, was at home: what if there was a bombing raid? We rushed back. Our boy was asleep, the window curtained by a bedspread. But we couldn’t sleep. Sirens wailed, announcing that everyone should go down to the bomb shelters.

We sent Mum and the kids to the bomb shelter while we stayed in the yard. We sat on a bench and ate the pastries bought that day. It was the first night of the war. A sort of fireworks festival broke out in the skies: searchlights were swinging about, intertwining and criss-crossing; flak guns were banging from the roofs of big buildings; shell bursts were flashing out like white lowers in the searchlights. We heard the sound of footsteps running down the street, but in the yard it was quiet. Around us the apartments were empty. It seemed like only we two were left on the surface – my wife and I. We began feverishly discussing the war: it would be fine to go to the front together, the only concern was to make arrangements for our son. That same night it was decided I would join the army and go to the front. I would refuse my draft exemption papers [awarded to men with certain skills and trades – Trans.], give up art, and become a soldier.

The sirens sounded the All-Clear and the crowds headed home. Everyone was excited and only the sleepy kids, nodding in weary arms, made people go back to their flats. We rushed to our kinfolk, bunked the kids down, and went out onto the street. No one could sleep . . .

CHAPTER TWO

Movie With a Happy Ending

In the morning I ran to work and announced our decision. Leva said: ‘Galka [a diminutive of Galochka – Trans.] is right, we have to join up.’ The four of us – Leva, Nikolai, Boris and I – went to the voenkomat. The voenkom [i.e. military kommissar, a voenkomat being his office – Trans.] said everyone should go home and work, instead of holding up mobilization. We returned to the museum dissatisfied. An idea entered our minds. We could petition the Editor of Pravda [the main organ of the Central Communist Party Committee – Trans.] – perhaps he could get us to the front! We ran to the editorial office and insisted on being seen. The Editor listened to us and said he would do everything possible. Four days later we were called back and told we could work in the voenkomats, drawing slogans and posters. We wanted to join up for combat! But diploma students were exempt from the draft and would not be taken to the front. Instead, we produced placards – the first placards on the topic of the war in the exposition – and I returned to my picture about the German occupiers in the Ukraine . . .

But one day, as the four of us were walking to the Institute, recruiting for the Opolchenie [i.e. Territorial Army or Home Guard – Trans.] began in a small office in Pushkin Square. When we arrived registration was under way. The place was noisy and crowded. People mobbed around a desk and we joined the queue, rapidly making our way to the front. All the time, men were arriving, taking their places in line. Soon the room could not hold them all, and those who had already enlisted were glad to get out of the crush and into a crowded corridor. Enough people had gathered for a whole platoon, or even a company, and it seemed to us that this would be a mighty force; that it would play an important part in the war; that all we had to do was turn up at the front and the war would be over (that was what we told our wives). Before we left, we were told to show up at the Hotel Sovietskaya next day: that was where the Leningradsky district Opolchenie Headquarters was located.

I came home and proudly told Galochka that we had enlisted in the Opolchenie. She immediately began to sew a backpack with straps: the kind a soldier would need for storing all necessities. Galya also wanted to enlist as a nurse. But what to do with Igor? Mum didn’t want to look after two children – her own ten-year-old Dimka and our four-year-old – because on top of everything, she had a job to go to. Then, in the morning, it was announced that all women with kids were to be evacuated from Moscow. Galya would go to Penza with Igor.

As for me, at last I was signed up and shorn. The first night as an Opolchenie soldier I should have spent in the school, but I ran away and came back at dawn. I jumped out of a window and returned the same way. I was not yet used to the fact I was now a soldier. Also, it seemed pointless to sleep on the floor in the school when I could go home and see my wife off to the evacuation, and carry her trunk to the assembly point. When I came home, Galya’s mother took the children out, leaving the room free for us to say goodbye. It was our final farewell and we both understood it might be for good. At that moment I felt the war more keenly than when I was issued with a rile. We couldn’t fall asleep on this last, so short-lived night. Tomorrow I would not be able to come home again . . .

We were in the Opolchenie now. Our formation was dressed in a variety of suits: pants, jackets, shirts all different shades – white, black, grey, dark-blue. The only uniform thing about us was our close-cropped heads. They marched us through the beloved streets of Moscow: ‘Left foot! Left foot! One, two, three . . .’ And led us into the hall of what had been a first-class restaurant, full of joy and music just yesterday, but now there were no white tablecloths, and the tables were lined up in a row. And it wasn’t a ceremonial dinner: motley-dressed men with shaved heads sat at the table, jammed up against each other, while our section leader ladled pearl-barley soup from an aluminium saucepan. We courageously held out our aluminium bowls and chewed our black bread. Well, if this was what it took to achieve victory, we would eat this ‘shrapnel’ with great appetite; we would scrub the bowls clean and ask for a second helping, tapping with our aluminium spoons. Where had they dug up this amount of aluminium crockery? It was amazing!

Before leaving for the front we were lined up in the school yard. The street beyond the fence was packed with women and kids, who were standing devouring us with their eyes. We were trying to stand still, while displaying a good deal of bravado, to let them see what good warriors we were, despite being dressed so diversely. I was wearing white pants and a brown jacket. My head was shaved smooth as a watermelon, and a straw hat was perched upon it (those without hats had peaked caps or skull caps, for it was no good having a shiny new-shaven head).

We had been marching in the streets, singing songs, keeping in step, which did not come at all easily for me. I tried to tap with my left foot as firmly as possible, but it was painful. And I was frequently mixing up my feet, which seemed unfair! Now, standing on one spot, I was trying to keep in step on the turns, so as not to bring shame upon myself in front of the women who had come to see us off. We were facing the fence and I saw hundreds of eyes staring at us, some sparkling with tears. Women were nodding to us, waving their handkerchiefs, and trying to cheer us up with smiles. I noticed the radiant blue eyes of my wife in the crowd, she too was smiling, all the while gripping the iron rods of the fence with her thin hands. After the command, ‘Count off!’ the words ‘At ease! Break up!’ came like music.

And that was it. The string of shaven heads broke up, dispersing into small, individual beads, like drops of mercury, and we ran to the gate and into the street. The women were crying, standing with bowed heads in front of their men. One of them, as if apologizing, silently stroked his wife’s shoulder. Another had a child in his arms. Yet another was consoling his wife, trying to impart cheer and unconcern to his voice. But a heavy weight lay on everyone’s soul. Everyone understood that something serious was happening, yet couldn’t believe it. And somewhere, in a corner of one’s mind, there was still the idea that all would pass and not turn out for the worse; that it would all finish like a movie with a happy ending.

We were consoling our wives that soon we’d come back with victory. I told mine: ‘Don’t take any winter clothes for the evacuation – everything will be over by autumn.’ We had got used to believing our government knew some secret way to win, and even if a retreat was under way, why that was no more than a strategic move, and before we had time to reach the front the war would be over and the enemy on the run. Everything would be fine, like in a good film. And our wives were going to the rear in an orderly fashion and would be waiting for us to come home, battle-seasoned and grown stronger with victory on our steel sabres. Well, if need be, we could go into combat for victory and endure the pearl-barley porridge and the separation.

But in the eyes of the older guys – amongst us there were many who had been through the Revolution and the Civil War – there was disquiet. It seemed to me that their wives had packed their bags more thoroughly, not forgetting even a trile. They were bringing their handkerchiefs up to their eyes more frequently, and looking at their husbands with longing. Some of them couldn’t restrain themselves and began to cry, throwing their arms around the necks of their shaven husbands.

I pushed through to my wife and embraced her. We kissed, there in the crowd, the same way as the rest, feeling shy before no one. I was hugging her and we were trying to retain, to absorb, the memory of every touch. We came out of the crowd and stood under a tree. It was growing dark and the command to return was imminent. I was kissing my wife and we were both feeling a keen lust for each other. Standing in the shade of the trees she was prepared for anything, but then a thought rushed through my mind: what if someone saw? And so I didn’t take what a person can give as the best feeling in the world, if born of love. I always regretted that. I regretted giving in to embarrassment and the fear of violating the rules of behaviour. Whether I was lying under falling bombs, knocked about by typhus, or blinded and ready to take my own life, I always regretted not making love to my wife back then . . .

CHAPTER THREE

Here, There, and Somewhere Else

On the night of 5 July 1941 we were marching along the blacked-out high road. Fedya Glebov was singing, jauntily starting one new song after another, including our favourite, ‘Along the Valleys, Across the Uplands’ [a popular soldiers’ song of the Russian Civil War of 1918–22 – Trans.]. Our company, which included students from the Surikov Institute of Arts, was part of the 11th Rile Division of the Opolchenie [renamed 18th Rile Division on 26 September 1941 and later reorganized into the 11th Guards Rile Division – Ed.]. We marched smartly, our light-coloured pants visible in the darkness, moving away from Moscow . . .

By the time daylight dawned we weren’t singing anymore. There was no more familiar bitumen beneath our feet, and we were falling out of step. The rear of the column was lost in a grey mist, and we – sick of tramping – began to wonder: why are they driving us so hard? It’s time to have a rest! Well, if this was what it took to win the war, we could march till morning. But we had been on the move both night and day, and we were sleepy.

During the march we had been overtaken by the first trucks carrying weapons and uniforms. Since we were Opolchenie, and a newly formed division, we were being armed and fitted out on the road. Trucks would drive up, the column would stop, and packs would be thrown down from the vehicles so we could be issued with their contents straightaway. Initially, we had been a motley and colourful crew, armed with Polish riles, then with old German models – though there was no ammo for them. But day by day we were getting everything we needed for the war. We got ten-round SVT rifles [a Soviet semi-automatic weapon of the early war period – Trans.] and uniforms. At first there wasn’t enough for us all, but gradually we received blouses, pants, foot-wrappings and puttees. All of this changed our appearance and we looked at each other as comparative strangers. There were many funny moments with the foot wrappings and puttees, the handling of which required practice, so as not to get mixed up, and not to rub one’s feet sore.

Our life, difficult even without this, was complicated by the fact so many different things had been accumulating in our backpacks: clothes, hand grenades, Molotov cocktails, and so on. On top of all this we were issued with ammo: a common individual allowance plus a reserve, which was supposed to be carried in the unit transport. But when we had no transport everything had to be carried on our backs. Then our leading singers would strike up songs and we would join in. If you didn’t sing you’d be in a stupor. Songs helped us to march, to hold out.

The sun, the heat, of that July – who of my generation could forget?! The road was white with dust, which shrouded us. We were constantly thirsty, but even the most disciplined among us had an empty flask. Suddenly, a shriek! Someone would reel, stagger a few steps, and fall into the dust. Medical orderlies would run up, drag the invalid to the roadside and bring him to his senses – it was sunstroke. But we were not allowed to stop, to step out of formation. Even if your comrade fell, you couldn’t help him. You had to march on. Just keep going, the orderlies will deal with it. ‘Don’t fall out of step!’ And so the column flowed around the fallen and moved on. This was the rule of march. Back then it shook me. I even had a quarrel with a starshina [i.e. sergeant major – Trans.] when I tried to help a guy who’d fallen next to me.

On the fourth day of the march they gave us a treat. They took some heavy English ‘Hotchkiss’ machineguns and boxes of ammo from the vehicles. To carry all this would be unbearable. The machinegun shield – the heaviest thing – was carried by one man, the tripod by another, the ammo by two others. Machineguns would be disassembled and the parts distributed between the soldiers. Heavy machineguns, company mortars, ammunition, all were loaded on the soldiers’ backs. The amount carried by each of us, when put on a blanket and tied in a bundle, was difficult to lift off the ground. On top of all, we were laden with hand grenades and Molotov cocktails for anti-tank combat. And marches were long, 50–70 kilometres each. It was beyond one’s power to hold out a whole day on the white-hot road. Yet we kept marching, filling the air with our songs.

Time and again our unit was shifted from one sector of the front to another. From near Vyazma we were sent on trucks to Orel, then to the Bryansky Front, then to Elnya, and then back to Vyazma again. We dug defence lines and anti-tank ditches. As soon as we were ready to face the enemy, an order would come and we moved on. We understood that this fever gripped not only us but those above. No one knew how to stop the enemy. It seemed to me that we were rushing around like hares in a circle: we’d been here, there, and somewhere else, and kept coming back to Vyazma.

They were always hammering into us: ‘Hard at drill – easy in combat’ [an aphorism of Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov, b. 1729, d. 1800 – Trans.]. But we were incapable of distinguishing the two. We were on the march twenty hours a day. We would have only one stop: an hour for lunch. But it was not easy to provide soldiers with food on a forced march. We were fed with millet gruel. Yet these marches trained us well and we learnt a lot: how to wrap our legs with puttee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Preface by the Russian Editors

- Note on Russian Names

- Part 1 Captivity

- Part 2 Red Partisan

- Epilogue

- Glossary