- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A fascinating and accessible history of textiles, including the key personalities and inventions which revolutionized the industry, together with the East End workshops and the creation of artificial materials such as rayon. Textile expert, Fiona McDonald, includes tips on the care and repair of materials and advice on whats worth collecting and the best materials to wear, as well as safe cleaning, tips on collecting.In addition to a handy glossary of textile terms, there is an A-Z of different textiles, full of interesting facts did you know that velvet was originally made from silk and its name derives from the Latin word, vellus, meaning fleece, or that cabbage was the term used in the rag trade to refer to the extra outfits clever cutters created and sold off the books by careful placement of the pattern. A fascinating and often surprising subject area explored at an accessible but informative level.Did you know? Peau de Soie is a heavy satin which was used for wedding dresses at the turn of the last century. The word satin is derived from Zaytoun, an area of China where it was first made We have lost many evocative names for colors over the years, including bouffon (darker than eau de nil) cendre de rose (gray with pink nuances), dust of Paris (ecru), esterhazy (silver-gray), flys wing (graphite) and terre dEgypt (rust)

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion DesignPART I

The Raw Materials

How much do we really think about the origins of our clothes? Like so much of everything around us we probably take it for granted. The cotton shirt, linen trousers, the environmentally sound shopping bag, the carpets we walk on, the curtains we draw to keep out the dark, the woollen blankets, the lace doilies, the rags used for polishing the car. Textiles surround us and yet do we ever stop to think where they all came from?

In the first part of this book we will look at the raw materials from which some of those everyday items are made. We will discover that flax is a bast fibre which means the inner core of the stem of the plant is used to make thread. Cotton behaves more like wool, and silk is something that stands alone in the textile world. Wool was the backbone of the English economy for centuries and two separate continents made fabric out of similar products using similar techniques without the knowledge of each other.

Whether or not Adam and Eve covered their newly discovered shame with fig leaves is highly debatable. It is far more likely that they and the other early ancestors used first animal hides and then bast fibres before they got down to the nitty-gritty of spinning and weaving.

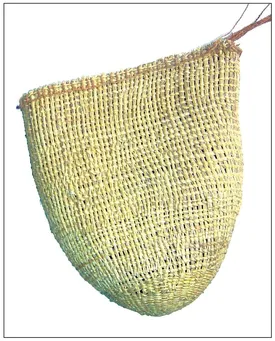

An example of basketry made by a contemporary Indigenous Australian craft person whose work can be compared with some of the earliest textile finds.

CHAPTER ONE

Plant Fibres

Flax, Hemp and Other Bast Fibres

Flax and hemp are probably the oldest known plant fibres in the world used for making textiles. They are still in use today. Linen, a fabric synonymous with good quality, makes the best Manchester and its characteristic crispness in classic clothing speaks volumes of good taste. Yet flax and hemp are humble plants whose appearances belie the silken fibre hidden inside them; it is a wonder that mankind ever discovered how to turn them into yarn. These fibres are known as bast and are found within the stems of certain plants, for instance: flax, jute, hemp, willow, ramie and certain other nettles. The fibres are held together in bundles of 30 to 40 fibres. Each stem has approximately 30 bundles.

There have been traces of processed flax fibres found within a cave in the Republic of Georgia. The thread survived as an imprint in a piece of baked clay and has been dated to 34,000 years ago. Of course, a finding this old sparks heated debate as to the accuracy of the date given to it but the archaeologists are adamant that the methods they have used for both identifying the fibre and telling how old it is are dependable. Such a find is rare but it doesn’t stand alone. A few years before the Georgian Republic find another imprint of a fibre was discovered in the Czech Republic and was dated to 28,000 years old. The hypothesis about these most ancient of textile fibres is that the plants from which they were processed were wild, not cultivated and that they were harvested from the surrounding area.

Other ancient textile finds include bast fibres unearthed in the famous Lascaux Caves in France dating to 18,000 years ago. Nets made from two-ply willow bast have been found in Finland and have been carbon dated to 8000 BC. Flax or hemp bast nets from Lithuania and Estonia have been found which date to between 6000 – 4000 BC.

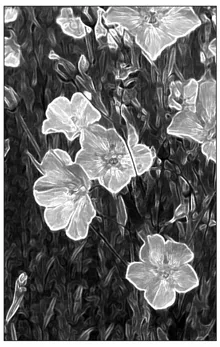

The flax plant.

Bast fibre plants like willow were probably used for their excellent basket weaving properties. The long, flexible young branches could be woven and twisted into shape. The discovery of using the even more pliable inner fibre may have occurred when such branches were left out in the wet. The outer fibre rotted exposing the bundles of inner fibre.

The most popular of bast fibres and one that became the most widespread is flax, followed closely by hemp, from which linen is made. Flax (Linum usitatissimum) is known to have been cultivated about 5,000 years ago in areas that are now modern day Iran and Iraq. Its versatility to grow in different climates and soil types meant that its popularity as a crop spread quickly and within 2,000 years it was to be found growing in Syria, Egypt, Switzerland and Germany.

Although it is tough, flax is the more temperamental of the two plants. It doesn’t like heavy clay soil or dry gravelly soil very much whereas hemp will grow almost anywhere.

Flax and hemp produce fibres that make beautiful and strong textiles but their appeal as a crop is also because both of them have other properties. They both produce edible and medicinal seeds; these can be further processed for oil which can be put to various uses. Linseed oil was a long-time favourite medium for oil painters who used to it thin paint and facilitate glazes, and linen or hemp sails were often treated with oil from the seeds to make them waterproof (hemp is known to be resistant to the rotting effects of salt water). The same seed can be used for human consumption or as a supplementary food for animals.

With such versatility of purpose and its ready adaptation to different environments flax is one of the oldest agricultural plants of any kind.

Flax is an annual crop that grows to approximately 1.2 metres tall. The leaves are a dull green and the flowers a pale blue (sometimes red) each with five petals. Flax plants also bear fruit, round dry cases containing several glossy brown seeds. Originally flax grew wild from the East Mediterranean all the way to India and in some parts of South America. Other varieties of flax include Silene Lineold which grows well in the colder parts of Europe and Silene Linicola identified as the variety grown in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Flax in China

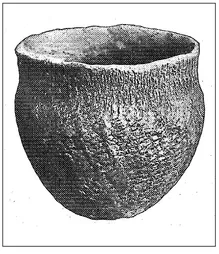

In China the first plant fibre to be cultivated for its use as a textile product was not flax but hemp, predating the use of silk (which was always kept for more luxurious costly items). Hemp fibres imprinted in pottery shards are estimated to be over 10,000 years old. Hemp linen was the main source of fabric fibre, even over flax, until the introduction of another bast fibre, ramie, and then the introduction of a completely different kind of fibre, cotton.

Pottery shards with fibre texture imprinted on it.

Linen, either from flax, hemp or ramie fibre would have been grown, harvested and turned into cloth by most family groups to make into their own clothing and home adornments. However, it would not have taken long before its marketable dimension was realised and it was produced on a commercial scale to be traded for more exotic or not so easily obtainable goods.

Egyptian linen

Egypt presents us with some of the earliest visual records of flax in the form of murals on tomb walls. The paintings depict its growing, spinning and weaving as an industry. In other documentation linen is referred to it as ‘woven beauty’ or ‘woven moonlight’. Linen was the most important textile of the Egyptians. The Pharoah Ramses II, whose mummified body was discovered in the late Nineteenth Century, was wrapped in perfectly preserved linen bandages, as was the body of the daughter of a priest serving the god Ammon, 2,500 years ago. Linen curtains provided for Tutankhamen’s tomb were reportedly in a good state of preservation. It is also in Egypt that records survive of linen being an industry.

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder, 23 – 79 AD, was a Roman administrator historian who, amongst other things, wrote about flax, its cultivation and uses and made social comments about the various people who worked it and wore it. He begins the chapter on flax in his Natural History by upbraiding certain countries for growing flax in order to turn it into sails and rigging for ships. He says:

What audacity of man! What criminal perverseness! Thus to sow a thing in the ground for the purpose of catching the winds and tempests, it being not enough for him … to be borne upon the waves alone’. Natural History, Book XIX.1

According to Pliny the excellent properties of flax and its usefulness for making sails, as well as fine clothing for ladies, had led to the bridging of geographical distances, bringing Egypt into close proximity with Italy: and all down to one humble plant. It seems, therefore, rather churlish of the women of the Serrani family to make a habit of never wearing linen as Pliny further informs us (it probably was more due to the fact that it creases dreadfully).

Pliny’s work is entertaining as well as informative. He goes on to talk about the different properties of linen made in different parts of the world. Egypt’s linen is not as strong as others but is of a particular fineness. In Germany, apparently, they wove their flax inside deep caves and this gives it certain highly desirable attributes. Flax is used for making everything from sails to hunting nets to dresses for men and women. Pliny describes different types of linen, comparing a fabric with a distinct downy nap with one that is smooth and lustrous and so underlining the plant’s numerous potential.

In the second chapter of Natural History Pliny discusses how to grow flax, noting that it damages the soil considerably by sucking all the goodness from it. It is therefore, he states, an excellent crop to be grown along the banks of the Nile where it is subject to annual flooding. Flax does in fact deplete the soil of nutrients so the flood plains of the great river would have the ability to renew the soil’s rich minerals in the annual floods.

Processing flax

Pliny not only provides a commentary on the who and where of linen but gives a detailed description of how it is cultivated, harvested and processed.

In our part of the world the ripeness of flax is usually ascertained by two signs, the swelling of the seed, and its assuming a yellowish tint. It is then pulled up by the roots, made into small sheaves that will just fill the hand, and hung to dry in the sun.

It is suspended with the roots upwards the first day, and then for five following days the heads of the sheaves are placed, reclining one against the other, in such a way that the seed which drops out may fall into the middle.

Linseed is employed for various medicinal purposes and it is used by the country people of Italy beyond the Padus in a certain kind of food, which is remarkable for its sweetness: for this long time past, however, it has been in general use for sacrifices offered to the divinities.

After the wheat harvest is over, the stalks of flax are plunged in water that has been warmed in the sun, and are then submitted to pressure with a weight…

When the outer coat is loosened, it is a sign that the stalks have been sufficiently steeped; after which they are again turned with the head downwards, and left to dry as before in the sun: when thoroughly dried, they are beaten with a tow-mallett on a stone.1

Pliny’s description goes on to include what happens to the stuppa the part of the inner fibre closest to the outer coat. The flax here is inferior to the innermost fibres and is used mostly for candle wicks. The outer coat of the flax is used as fuel for fires. The spinning of flax, says Pliny, is an honourable employment, even for men. Once the flax has been spun it can be beaten to make it suppler and after it is woven it will improve with further beating. Pliny estimates that for 50 pounds of harvested flax 15 pounds of flax will be combed out ready for spinning.

Flax on the move

From Egypt the art of spinning flax spread first to the Hebrews, then to the Assyrians and Phoenic...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Timeline

- PART I - The Raw Materials

- PART TWO - Processing

- PART THREE - Surface Decoration

- PART FOUR - The Industrial Revolution

- PART FIVE - Textiles in the Modern World

- Glossary

- Textile Places of Interest

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Textiles by Fiona McDonald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.