- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Florence cathedral hangs a remarkable portrait by Uccello of Sir John Hawkwood, the English soldier of fortune who commanded the Florentine army at the age of 70 and earned a formidable reputation as one of the foremost mercenaries of the late middle ages. His life is an amazing story. He rose from modest beginnings in an Essex village, fought through the French campaigns of Edward III, went to Italy when he was 40 and played a leading role in ceaseless strife of the city-states that dominated that country. His success over so many years in such a brutal and uncertain age was founded on his exceptional skill as a soldier and commander, and it is this side of his career that Stephen Cooper explores in this perceptive and highly readable study.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sir John Hawkwood by Stephen Cooper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

‘A Fine English Knight’: France, 1360–2

He thought that to return to his own country would bring him no profit.

Jean Froissart, Chronicles

In 1314 a huge English army went down to devastating defeat at the hands of Robert the Bruce, at Bannockburn near Stirling. The Scots invaded England, occupied parts of the North and imposed peace on their terms. The English grip on Scotland was broken for a generation, some would say for ever, and the reputation of their arms reached an all-time low (though it is possible that they learned much from their defeat). By 1360, after the English victories at Halidon Hill, Crécy and Poitiers, the situation was dramatically reversed. The reputation of English soldiers rose to unprecedented heights. John Hawkwood was one of the beneficiaries, and possibly one of the agents, of this transformation.

Hawkwood’s Origins and Early Life

The chronicler Jean Froissart (1337–1410) tells us that:

There was in the march of Tuscany in Italy a valiant knight who was called Sir John Hawkwood [Messire Jean Haccoude], who carried out many armed enterprises there, and who had done so before. He had come there out of the kingdom of France when the peace was made and negotiated between the two kings at Brétigny of Chartres. At that time he was a poor bachelor-knight. He thought that to return to his own country would bring him no profit; and when it was agreed in the peace treaties that all the men-at-arms had to leave the kingdom of France, he made himself leader of a band of companions, whom the people called Late Comers [Tards-Venus]. They arrived in Burgundy and in that place there assembled a great multitude of these bands of English, Bretons, Gascons, Germans and members of Companies of all nations …

Note the obscure beginnings. Hawkwood is already a knight, but a ‘poor’ one, and he is a mere ‘bachelor’ – on the lowest rung of knighthood. In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, it is the squire who is described as ‘a lusty bachelor’, while in Marco Polo’s account of his travels, Marco is presented to the Great Khan as ‘a young bachelor’, though he was not a knight at all; but the term does not necessarily mean that the knight was still learning the trade. Sir John Chandos was described as a bachelor at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, and he was very far from being an apprentice.

Froissart also mentions Hawkwood in his account of an interview with a Gascon called the Bascot of Mauléon, in an inn called The Moon in the Pyrenees. This Bascot may be a creation of the chronicler’s imagination, but his story has the ring of truth, and, looking back, he tells us that Sir John was both a ‘fine English knight’, and the captain of a company (or route). The veteran soldiers are described in glowing terms:

I tell you that in that assembly there were three or four thousand really fine soldiers, as trained and skilled in war as any man could be, wonderful men at planning a battle and seizing the advantage, at scaling and assaulting towns and castles, as expert and experienced as you could ask for …

Very little is known about Hawkwood’s early life. Modern historians are not even sure when he was born, 1320 being the conventional date. Some of the Italian chroniclers tell the ridiculous story that he was born in a wood frequented by hawks,1 but the serious point is that he was undoubtedly a commoner, in an age which attached greater importance to the circumstances of a man’s birth than our own. His father Gilbert was a tanner in the village of Sible Hedingham, though he also owned land and was not a poor man. Hawkwood was a younger son, with an elder brother, also called John and referred to in later conveyancing transactions as ‘John the Elder’; he had a younger brother called Nicholas and four sisters. Under the system of law which prevailed in most English counties, the eldest son inherited family land, whether or not the father made a will, and Gilbert Hawkwood’s will therefore mentions only personal property: cash, furniture, animals and cereal crops. When he died in about 1340 Gilbert left our John Hawkwood only £20 and 100 solidi (shillings), though each of the three sons was also given five quarters of wheat, five of oats, and bed and board for a year.

Some time after the end of the year specified in Gilbert’s will, Hawkwood did what countless other younger sons in England have done, and left home to become a soldier. Filippo Villani wrote that an uncle who had served in the French wars helped him, and that could well have been so. Sible Hedingham is contiguous with Castle Hedingham, which had an important castle, seat of the de Veres since the twelfth century, and it is often also assumed that Hawkwood first went to France as part of the retinue of John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford (1313–60). This de Vere was one of Edward III’s principal commanders: he fought in Scotland and at Crécy and Poitiers in France, and was killed at the siege of Reims in 1360. There are traditions that Hawkwood fought alongside de Vere, just as there are stories that he was knighted by the King or the Black Prince, but there is no hard evidence for any of this and it is equally likely that he became a knight by other means. To understand why, we need to look at the type of warfare the English were involved in, during the first phase of what was (much later) called ‘the Hundred Years’ War’.

The Hundred Years’ War and the Reputation of English Arms

There were several reasons for the great conflict between the English and the French kings, which (conventionally) began in 1337 and lasted until the English were finally expelled from France in 1453. French support for Scottish independence was one. Another was the English King’s uneasy position as vassal of the King of France for his fiefs in Gascony in south-west France. Edward III’s claim to the French throne (through his mother Isabella) became a third, though he only asserted this after the commencement of hostilities. Underlying it all was a keen desire on Edward’s part to humble the Valois dynasty, whom he came to regard as usurpers.

During the reign of his father Edward II (1307–27), English armies had suffered a number of disasters, both in Scotland and Gascony, and, when Edward II was deposed and murdered, the standing of the monarchy plunged to new depths. His successor showed very quickly that he was made of sterner stuff. The young Edward III restarted the war with the Scots and defeated them at Halidon Hill, near the border, in 1333. This was a great victory, celebrated in particular by the York chronicler, who had no time at all for the Scots, but Scotland was always a sideshow and, once the continental war began in earnest, most of the fighting was done in France. The French raided Southampton, Portsmouth, Dover and Folkestone in the 1330s; they came burning all along the south coast in 1377, and they and the Scots ravaged the North of England in 1385; but they were never able to equal William the Conqueror’s feat of launching a full-scale invasion across the Channel. By contrast the English occupied large parts of France throughout the long war and mounted long-distance armed raids (chevauchées) into the very heart of the Valois domains. Hawkwood was involved in the fighting along with many other Essex men.

At first the war did not go well for Edward. The Kingdom of France (though smaller than the Republic today) was twice as big as England, much more densely populated and potentially very much richer. Moreover, her Capetian monarchs had made her the leading military power in the West. Edward’s early strategy was to buy alliances in the Low Countries and the Holy Roman Empire, with money borrowed in Italy. This was a failure, but he learned by his mistakes and switched to a strategy involving a number of separate strikes, at the same time exploiting wars of succession in the French provinces. The year 1346 was a ‘Year of Victories’: Henry of Grosmont raised the siege of Aiguillon in Gascony; the King’s own campaign in Normandy and Picardy culminated at Crécy, where the English archers shattered the French cavalry; and the Archbishop of York and the northern barons defeated the Scots at Neville’s Cross near Durham, capturing the King of Scots, David Bruce. In the next year, 1347, the King’s forces took Calais after a siege lasting eleven months, and Sir Thomas Dagworth captured Charles of Blois, the French claimant to the Duchy of Brittany, at La Roche Derrien. In 1349 Edward founded the Order of the Garter, to commemorate his victories and assert the justice of his cause.

Because of the devastating effects of the Black Death, there was a lull in the fighting for some years, but then a new series of attacks on Valois France began. The Black Prince led two chevauchées in 1355 and 1356, the first from Bordeaux, across the Langue d’Oc to Narbonne and back, a second northwards across the Loire. As the Prince made his way back to Gascony after the second raid, the French caught up with him near Poitiers, where he inflicted another defeat on them, more shattering even than Crécy. The French suffered 2,500 dead, and 3,000 prisoners were taken. Among the dead was the Constable of France, Walter of Brienne, dictator of Florence for a few brief months in 1342. Among the prisoners was Jacques de Bourbon, a member of the French royal family, captured by the Captal de Buch but resold to the Prince for 25,000 écus. Most catastrophic of all for the French, King John II – ‘John the Good’ – fell into the hands of the English. It was the long list of noble prisoners which most impressed the chronicler in Montpellier who wrote the curiously named Thalamus Parvus. Hawkwood would have been about twenty-six at the time of Crécy and thirty-six at the time of Poitiers, but it is not known whether he fought in either of these battles. He could have done, but he is not recorded among those rewarded with money, annuities or offices. By one means or another, he became familiar with English strategy and tactics.

The capture of John II gave Edward III immense bargaining power and he was able to negotiate a favourable peace treaty four years later, despite the relative failure of his last campaign in 1359. At Brétigny in 1360 the French agreed to cede the town of Calais, the county of Ponthieu (near the Somme) and a vast new Duchy of Aquitaine, far larger than the old Gascony. This Duchy was ceded in full sovereignty, so that the Plantagenets would no longer have to do homage to the Valois. In return Edward agreed to give up his claim to the French Crown, evacuate his forces from those parts of France not ceded, and release King John against the promise of 3,000,000 gold écus, an écu being worth about 40p (or 8 shillings) in 1360. This was a truly enormous sum, though it was payable by instalments. It was seven times larger than the ransom set for the King of Scots three years before.2

In their war with the Valois, Edward III and the Black Prince restored the reputation of English arms. Jean le Bel thought that:

When the noble Edward first gained England in his youth, nobody thought much of the English … Now … they are the finest and most daring warriors known to man.

The Italian poet Petrarch thought much the same:

In my youth the English were regarded as the most timid of all the uncouth races; but today they are the supreme warriors; they have destroyed the reputation of the French in a succession of startling victories, and men who were once lower even than the wretched Scots have crushed the realm of France with fire and steel.

From the time they started to invade France in strength, the English aimed to inflict economic damage and show that the Valois usurper could not guarantee the security of his people. Geoffrey le Baker’s chronicle of Edward III’s march through Normandy in 1346 is full of images of destruction while, after the fall of Calais, Thomas Walsingham (a monk at St Albans) wrote disapprovingly that there was scarcely a woman in England who was not decked out in some of the spoils. The chevauchées mounted by the English were a form of attrition. The idea was to ride through those parts of France not already in the hands of the English or their allies, burning and raiding on a wide front, but avoiding pitched battles and sieges. This strategy worked well in the 1340s and 1350s, when men of the calibre of Henry of Grosmont and the Black Prince were in charge. It is generally thought to have worked less well in the 1370s and 1380s. Even then a chevauchée, whether led by a common soldier like Sir Robert Knollys (1370), or by a royal prince like John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (1373), or Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester (1380), still had the power to inflict widespread damage. Thomas’s own account of the raid he led in 1380, as related by Froissart, was still enthusiastic:

I still remember my last campaign in France. I suppose I had two thousand lances and eight thousand archers with me. We sliced right through the kingdom of France, moving out and across from Calais, and we never found anyone who dared come out and fight us …

These expeditions were very lucrative. The laws of war allowed the victor to take prisoners, releasing them afterwards on parole, and collecting the ransom later. It was common practice for English soldiers to pay one-third of their profits to their captain, who in turn paid a third of what he earned to the Crown, and ransoms became marketable commodities. The Black Prince sold prisoners taken at Poitiers for £20,000, but even a knight or a mere squire could win an enormous sum. Sir Thomas Dagworth was offered £4,900 for Charles of Blois, while the ransom for the Count of Denia, captured at Nájera in Spain in 1367, led to protracted litigation in the High Court of Chivalry in England in the early 1390s.

The French war presented great opportunities to men like Hawkwood, and after Poitiers these included the chance to make a profit on their own account. The French King was a prisoner, and his kingdom was in chaos. The commoner Étienne Marcel seized power in Paris, while Charles ‘the Bad’, King of Navarre (and lord of extensive estates in northern France) made trouble elsewhere. The lower orders rose in a terrifying revolt known as the Jacquerie. The Free Companies – bands of soldiers fighting in their own interest and including hard men from many parts of Europe – took advantage of the breakdown of law and order to mount raids of their own. The devastation lasted for years, so that when Petrarch journeyed through France (once renowned for her beauty) he found her ‘a heap of ruins’.

In 1358–9 the Free Companies raided Burgundy, Brie and Champagne. A Welsh captain whom Froissart called ‘Ruffin’ concentrated on the area between the Seine and the Loire. Robert Knollys marched from Brittany to Auxerre, captured the town and sold it back to the inhabitants, though not before helping himself to choice items from the treasury of St Germain. The Gascon, Bernard de la Salle, in Froissart’s phrase ‘a strong and clever climber, just like a cat’, took the town of Clermont. This man became a rival to Hawkwood in Italy.

Hawkwood became a knight at this time. Froissart tells us that the man called Ruffin ‘made himself’ a knight, while Robert Knollys is said to have had two of his men confer the dignity on him after he had captured Auxerre. Hawkwood may well have done much the same thing. No great ceremony was required: a simple ‘accolade’ – a blow or a cuff – was enough, but it did normally require a knight to make another knight, and it is unlikely that he disregarded the conventions altogether, as ‘Ruffin’ did. Froissart describes him as ‘a poor knight, having gained nothing but his spurs’, but knighthood brought important advantages. For the professional soldier, the ‘Sir’ lent authority. It increased the new knight’s bargaining power, enabled him to make other knights (as Hawkwood later did in Italy) and meant that, if he was captured, he was more likely to be ransomed than killed out of hand. It was for this reason that Robert Knollys announced his worth to the world: his banner bore a simple message:

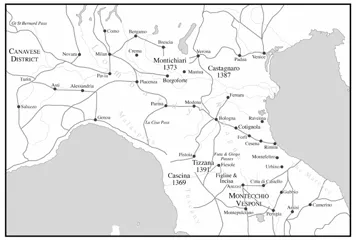

Montecchio Vesponi and Hawkwoods major battles.

Whoever shall take Robert Knollys

Will win 100,000 moutons .3

Will win 100,000 moutons .3

The Treaty of Brétigny and the Free Companies

With hindsight we can see that the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360 marked the end of a phase in the Hundred Years’ War. Many now take a dim view of that war and of Edward III’s achievement, but medievalists and military historians tend to be more kind, taking the view that Edward was one of our most successful commanders and rulers. There is no doubt that, for Hawkwood, the war proved a stepping-stone.

The terms agreed at Brétigny were ratified at Calais. Each side agreed to abandon the towns and fortresses in the provinces not ceded to the other, and an early date was set for evacuation. In accordance with these arrangements, most English soldiers returned home at the end of their contracts, as instructed, but, like many other members of the ‘free’ companies, Hawkwo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- List of Boxed Text

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Family Tree of Sir John Hawkwood

- Family Tree of Donnina Visconti

- Glossary

- Author’s Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Battle near Marradi, 1358

- Chapter 1: ‘A Fine English Knight’: France, 1360–2

- Chapter 2: From Captain to Captain-General: Italy, 1361–77

- Chapter 3: ‘The Best Commander’: Italy, 1377–94

- Chapter 4: Mercenaries, Condottieri and Women

- Chapter 5: English Tactics and the Notion of Italian Cowardice

- Chapter 6: Booty, Ransoms and Rewards

- Chapter 7: Leadership and Chivalry

- Chapter 8: Chevauchée and Battle

- Chapter 9: Strategy, Spies and Luck

- Chapter 10: The Atrocities in Romagna, 1376–7

- Conclusion: Hero or Villain? The Reputation of Giovanni Acuto

- Appendix 1: Francesco Sacchetti’s view

- Appendix 2: Hawkwood’s English Letters

- Notes

- Bibliography