- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

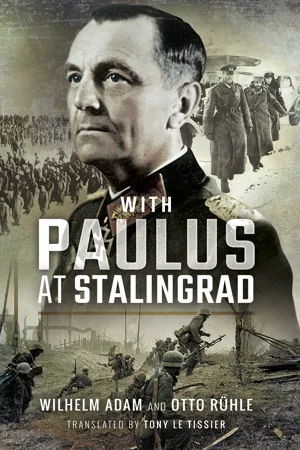

With Paulus at Stalingrad

About this book

This memoir from an aide to, and fellow POW of, General Friedrich Paulus documents a unique perspective on the horror of Stalingrad.

Colonel Wilhelm Adam, senior ADC to General Paulus, commander of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad, wrote this compelling and controversial memoir describing the German defeat, his time as a prisoner of war with Paulus, and his conversion to communism. Now, for the first time, his German text has been translated into English. His account gives an intimate insight into events at the 6th Army headquarters during the advance to Stalingrad and the protracted and devastating battle for possession of the city. In vivid detail, he recalls the sharp personality clashes among the senior commanders and their intense disputes about tactics and strategy, but he also records the ordeal of the German troops trapped in the encirclement and his own role in the fighting.

The extraordinary story he tells, fluently translated by Tony Le Tissier, offers a genuinely fresh perspective on the battle, and it reveals much about the prevailing attitudes and tense personal relationships of the commanders at Stalingrad and at Hitler's headquarters.

"Through his daily involvement with them, Wilhelm Adam is able to perfectly describe the characters involved, the tensions and despair amongst them and the pressure Paulus and his staff found themselves under as the Soviet pincers closed around the men of the abandoned 6th Army. The reader is presented with the hopeless situation faced by Paulus and his staff who, aware of the looming disaster from a very early stage are constantly denied the option of a withdrawal by Hitler and left to their catastrophic fate."— Grossdeutschland Aufklarungsgruppe

Colonel Wilhelm Adam, senior ADC to General Paulus, commander of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad, wrote this compelling and controversial memoir describing the German defeat, his time as a prisoner of war with Paulus, and his conversion to communism. Now, for the first time, his German text has been translated into English. His account gives an intimate insight into events at the 6th Army headquarters during the advance to Stalingrad and the protracted and devastating battle for possession of the city. In vivid detail, he recalls the sharp personality clashes among the senior commanders and their intense disputes about tactics and strategy, but he also records the ordeal of the German troops trapped in the encirclement and his own role in the fighting.

The extraordinary story he tells, fluently translated by Tony Le Tissier, offers a genuinely fresh perspective on the battle, and it reveals much about the prevailing attitudes and tense personal relationships of the commanders at Stalingrad and at Hitler's headquarters.

"Through his daily involvement with them, Wilhelm Adam is able to perfectly describe the characters involved, the tensions and despair amongst them and the pressure Paulus and his staff found themselves under as the Soviet pincers closed around the men of the abandoned 6th Army. The reader is presented with the hopeless situation faced by Paulus and his staff who, aware of the looming disaster from a very early stage are constantly denied the option of a withdrawal by Hitler and left to their catastrophic fate."— Grossdeutschland Aufklarungsgruppe

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access With Paulus at Stalingrad by Wilhelm Adam,Otto Rühle, Tony Le Tissier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Marching to the Volga

The death of the Field Marshal

Poltava, 14th January 1942. The officers of the 6th Army’s headquarters were sitting in their mess chatting. Lunch was already over and we were waiting for the commander-in-chief, Field Marshal von Reichenau. This was nothing unusual. Reichenau was not so strictly punctual with off-duty matters. He thought nothing of appearing in a tracksuit. We knew that he had made his usual cross-country run with his adjutant, the young cavalry lieutenant Kettler, which was why he had not noticed the time.

As we knew Reichenau’s habits, we were not concerned about his late arrival. But something unusual happened. He made his way uncertainly to the table as if he was having trouble standing upright. While he usually ate with pleasure and a good appetite, today he hesitated over his dish while groaning faintly. Colonel Heim, the 6th Army’s chief of staff, noticed this. He looked at Reichenau concernedly. ‘Don’t you feel well, Field Marshal?’

‘Don’t worry, Heim, it will soon be over. Don’t let me hold you back from your work.’

At this juncture I was asked by an orderly to go to the anteroom, where the army’s court martial adviser, Colonel Judge Dr Neumann, was awaiting me.

‘Can you please inform the Field Marshal that I need some urgent signatures from him? The post has to go to the Army High Command today.’

When I conveyed this wish to Reichenau, he said that the court martial adviser would have to wait a few minutes.

Outside I talked briefly with Dr Neumann and one of our orderly officers. Then the door opened and Reichenau appeared. He signed the files laid out for him. One of the orderlies stood ready to help him into his greatcoat, but this did not happen. The Field Marshal suddenly collapsed. We were able to catch the heavy man as he fell.

The shock hit me several minutes later as I stood in front of the chief of staff. ‘Colonel, the Field Marshal …’ Shocked, everyone ran into the anteroom. The once so strong and active Field Marshal hung slackly between two orderly officers, his eyes staring into nothingness. He appeared to have lost consciousness.

The 9th Army’s senior doctor, Dr Flade, had gone off to Dresden on duty two days earlier. I therefore called the senior doctor at the hospital in Poltava. We took the Field Marshal to his residence in a car.

The hastily summoned doctor identified a stroke, with a loss of consciousness. He shook his head thoughtfully. Reichenau’s right arm was drooping, as was the right side of his face.

Colonel Heim immediately informed the Army High Command and Führer Headquarters. Reichenau was commander-in-chief of Army Group ‘South’ as well of the 6th Army. Both were now without a commander. This was particularly awkward as Soviet units were successfully attacking our army front at two points.

Once Staff Surgeon Dr Flade had been ordered back by telegraph, Heim proposed to the Army High Command that Reichenau’s home doctor in Leipzig, Professor Dr Hochrein, who was at this time on the Northern Front, be flown to Poltava. The Army High Command agreed. On the 16th January Professor Dr Hochrein and Dr Flade landed in the same aircraft at the airport.

Reichenau’s condition had deteriorated considerably before the doctors arrived. The diagnosis was deeply located bleeding of the brain. There appeared to be a slight improvement on the evening of the 16th January. The assembled doctors wanted to make use of this improvement to convey the patient to Professor Hochrein’s clinic in Leipzig, especially if this difficult illness could perhaps still be helped.

Two aircraft took off at 0730 hours on the 17th January 1942. The Field Marshal had not survived, having died shortly before. Dr Flade took the dead man with him in the first machine; Professor Hochrein was in the second.

Lemburg, where they were to refuel, came into sight at about 1130 hours. The machine with the corpse started to land, but apparently touched down too late. It careered into the hangar and was totally destroyed. The corpse of the dead man was so cut up that it had to be bound together with bandages. Dr Flade broke his leg. In a letter of the 11th February 1942 written to General Paulus about the accident a short time later, he said: ‘My aircraft pilot thought that he could land in Lemburg and continued flying on to there, where the accident occurred at 1130 hours while attempting to land … it was a wonder we were not all killed, especially when one saw the machine afterwards.’

Hitler ordered a state funeral for Field Marshal Reichenau. The 6th Army was represented at the funeral by Major-General von Schuler, Reichenau’s aide-de-camp for many years. The hard fighting at the time did not allow a single section leader of our staff to attend.

Paulus, the new commander of the 6th Army

Field Marshal Bock was tasked with the command of Army Group ‘South’, taking over the command on the 20th January 1942. That same day Lieutenant-General Paulus, the newly named commander-in-chief of the 6th Army, arrived at Poltava.

Both men had difficult tasks ahead of them. Northeast of Charkov, near Voltshansk, units of the Red Army had driven the 294th Infantry Division out of its positions. The Soviet offensive either side of Isium at the junction of the 17th and 6th Armies had made a deep breach in our positions. Charkov, Poltava and Dnepropetrovsk were threatened, and there were no reserves available. Infantry and artillery battalions were withdrawn from those divisions not attacked and deployed to the right flank of the armies with a front facing south. A security division taken from the army’s rear areas was hastily extracted to prevent a further advance by the Soviet spearheads, and emergency battalions were formed from the army’s supply units for the immediate protection of the threatened towns.

The army’s situation was far from rosy when I collected Paulus from the airport. He stood tall and thin in front of me. He received my report with some reserve at first. Then a smile went over his gaunt face: ‘Also from Hesse?’

‘Yes, General,’ I replied,

‘Well then, we shall soon get to know each other, Adam.’ Then he greeted an old acquaintance who had accompanied me to the airport, our Mess Officer, Captain Dormeier.

His first question came when we were sitting in the car: ‘What does it look like at the front? I have read yesterday evening’s report from the army. Have things changed meanwhile?’

‘We are concerned whether the thin defensive front that we have formed by throwing units together can withstand the growing pressure from the Red Army. The chief of staff is very pleased that you have now arrived.’

Paulus immediately drove to see Colonel Heim, the 6th Army’s chief of staff, who, together with the other officers of the staff, had prepared a briefing for the new commander-in-chief. The situation map was brought up to date, together with the losses of the past few days. The Ia (Operations) and Ic (Enemy reconnaissance and defence) reported on their own fighting strengths, combat experience and intelligence. They explained the composition of the Soviet troops and the most recent reconnaissance results. Colonel Heim suggested that the combat teams of the various regiments and divisions be brought together under a new command. The choice went to General of Artillery Heitz, commander of the VIIIth Corps. Paulus knew him as a tough soldier, and so it fell to him. In fact Heitz quickly turned the combat teams into a combined force. He gave them strong support with a strict organisation of the artillery and enforced the construction of defensive positions. The 113th Infantry Division was given to the VIIIth Corps and deployed with its front facing the breakthrough point south of Charkov. The danger seemed checked.

During these days I discovered once more how carefully Paulus worked. The liberal attitude of the dead Reichenau was alien to him. Every sentence that he spoke or wrote was carefully weighed, expressing every thought clearly so that there could be no misunderstanding. If Reichenau was a decisive and responsible commander-in-chief, who specifically expressed himself with a strong inflexible will and determination, Paulus was exactly the opposite. Already as a young officer he had been called ‘Cunctator’, the waverer. His knife-sharp brain and his invincible logic impressed all his colleagues. I had hardly ever experienced him underestimating the enemy or overestimating his own strength and capabilities. His decisions came only after long, sober consideration after lengthy, detailed discussions with his staff officers, and were carefully structured to cover all contingencies.

To his subordinates, Paulus was a benevolent and always correct superior. I experienced this for the first time when I drove him to the subordinate corps and divisions. On the afternoon of the 28th February the chief of staff informed me that I was to escort Paulus to the front on the 1st March. Using this opportunity, he showed me a list of promotions that had come by post from the Personnel Office. I looked at it briefly. One name was underlined. The chief of staff shook my hand. I had been promoted to colonel with effect from the 1st March 1942. ‘I am telling you now so that you can tell the commander-in-chief early before he leaves. You can be proud of having been promoted from major to colonel in one year.’ And I was proud of it.

I quickly made up my situation map. The chief of staff advised me on the route to take. We would be away for three or four days.

By jeep to the subordinate corps

Next morning we drove off in a cross-country jeep to visit all the units at the breakout position east of Poltava, escorted by several motorcyclists. It was a clear ice-cold day. Even our fur coats offered scanty protection from the raw east wind. Frequent snow barriers blocked the route. Columns of soldiers from the rear services and local civilians could only clear these great obstacles for a short time. Walls of snow four metres high on both sides of the road reduced our view to the road. In only a few places was there an open view of the wide Ukrainian landscape, which spread out before our eyes like a desert of snow, its crystals sparkling like diamonds in the sun. Trees and bushes were only to be seen alongside streams and in the villages between the low, white-washed buildings covered with straw or shingles. Fat cranes puffed themselves up on the naked asters.

Paulus was communicative all along the way. He spoke of his concerns and expectations. ‘When I took over command of the 6th Army six weeks ago,’ he began, after a general discussion of the day’s events, ‘I was a bit concerned about how my relationship with the commanding generals would work out, they all being older than me and senior in rank.’

‘I had similar thoughts myself then,’ I said, ‘but then, from what I heard from the corps’ adjutants, I now have the impression that you command great respect from all of them.’

‘Certainly, Adam. I also believe that I have found the right tone. I will use this trip to make closer contact with them. The task of a commander is to establish a real confidence with his subordinates, in which mutual understanding is the most important factor. That eases the command considerably. Have you already met the generals personally?’

‘Colonel Heim introduced me to the commanding generals in the first few days, but I do not know all the divisional commanders. Until now I could only form a picture of them from the comments in their personal files.’

‘Use these few days. We will find out much about them. I would appreciate it if you would write down the impressions you have gained about the commanders upon our return.’

‘I will see, General, if I can speak with some of the regimental commanders. I will obtain opinions of them all, but I would like to make my own judgements.’

‘That is right and necessary. I presume that some heavy fighting lies ahead of us this year. I can look at your proposals when we start losing commanders. An error in filling a command post always has unfortunate consequences for the troops. So look at all of them carefully!’

We were driving down a hill. The vehicle began to slide and spun around several times on its own axis, until the driver corrected it. This brought our conversation to a halt, our attention being drawn to the mirror-like road.

We first visited the divisional commander, Lieutenant-General Gabke, who commanded the units in the westerly bulge. After a short orientation on the situation and the deployment of the troops, Paulus visited the artillery positions. They were located on open ground, being neither dug in nor camouflaged, so easily discernible to the enemy. This was quite irresponsible.

Paulus talked with the gunners and the gun commanders. ‘Is the gun in order? Have you enough ammunition?’

‘Yes, General!’ replied a gun commander.

‘Where are your gun carriages and horses?’

‘The horses are over there in the stables, the gun carriages right next to them.’ The gunner pointed towards the settlement only a few hundred metres away.

The commander-in-chief turned back to the gun commander: ‘Do you consider this position suitable? Why are the guns not camouflaged?’ Close by were some large haystacks. ‘Why not use those haystacks?’

The battery commander came running, fearing a ticking-off. But Paulus was no wild general who only gave reprimands, but, as in this case, set the soldiers light-heartedly to work. ‘I have spoken with your gunners about the positions the guns are in. They stand there as if on a presentation plate. Should the enemy resume his attack, your battery would be wiped out in a matter of minutes. Change position this evening and use the haystacks for camouflage!’

He had spoken quietly in a convincing and comradely manner. The battery commander stood before him with his right hand to his hat. ‘Certainly, General!’ He was so astonished, he could not say anything else.

‘Fine, just get everything in order.’ And with these words General Paulus left the baffled officer.

Has Timoshenko lost steam?

We sat back in the jeep and froze miserably, despite our fur coats. The next conference was to be at the headquarters of the VIIIth Corps in a village south of Charkov. Paulus said not a word, being engaged with his thoughts. Suddenly he looked up. ‘I do not understand why Timoshenko has not pursued his attack. The defensive positions we have just seen would not have stood up to an earnest attack.’

‘I had noticed it while we were at the artillery position. I only exchanged a few words with the observer, who had made a place for his periscope in the straw. He volunteered that Russians were as cold as we were and would certainly not continue the fighting. They were sitting in their settlements like us.’

‘That is certainly so. At the moment it is more or less a fight for the villages. But we must not overlook the fact that the Russians are significantly better equipped for the winter than we are, and that they can resume unexpectedly. In any case our headquarters in Poltava are as threatened as ever.’

‘I think, General, that Timoshenko has run out of steam, or he would have used the situation to his advantage.’

‘I don’t share your opinion, Adam. The Russians operate systematically, not taking risks lightly. I think we will discuss this question in detail this evening. Let us hear first how General Heitz, who has been here longer, assesses the situation.’

Heitz was already waiting for us. He was quite small, his movements concise. His jutting chin gave his small face a brutal appearance.

It was interesting for me to see how Paulus led the situation briefing. He seemed to be content with a superficial description. As a trained staff officer, he wanted to gain an exact picture of the situation, asking about the sources of information on the Soviet Army. He sharply distinguished between the essential and the inessential, considering again and again the various aspects of the enemy and demanding appropriate decisions.

General Heitz hinted specially at the strong Soviet tank units and then summarised: ‘Should the enemy hit us with a clenched fist here, Charkov could not be held and the 6th Army would be threatened in the rear. We lack large calibre anti-tank weapons. I request that some batteries of 88mm Flak be allocated to me. This would enable us to defeat an enemy tank attack.’

Paulus was fully conscious of the danger threatening at Charkov. Naturally he had to first check which Flak batteries could be made available. Turning to General Heitz, he said: ‘I will speak to the chief of staff about Charkov immediately. Hopefully, we will be able to help you.’

Our orderlies awaited us in Charkov, where we occupied quarters on a small housing estate. The two rooms and little kitchen were comfortably equipped and, following our drive in the icy cold, were comfortably warm. We had our dinner together in Paulus’s house. He was living immediately nearby. There were potato pancakes and bean coffee.

We sat together for a long time after supper. The commander-in-chief took up the conversation from that afternoon. ‘I have already told you, Adam, that I don’t share your opinion on the restricted operational ability of the Red Army. The Russians not only stopped our tanks in front of Moscow but, as you know, went into a counterattack on the 5th December 1941 with the Kalinin Front, threw our troops back a long way and inflicted severe casualties on us. I experienced the first part of this at the Army High Command.’

‘I have gone over this again thoroughly, General. In fact the Reds showed at Moscow what a great potential they still had. They soon spotted our weak points, broke through our positions and thrust deep into the interior. General Schubert, whose adjutant I was until November of last year, has written to me about it. His XXIIIrd Corps was surrounded near Rshev for several days and it was only by calling for a last effort that he was able to prevent himself from being surrounded. Many places that we took with heavy losses have been lost, such as Toropez, for example.’

‘Yes, Adam, the situation became very serious at Rshev, we lost so much valuable material. The Russian attack on the central front brought the Army High Command great difficulties. One hardly knew how the gaping holes could be closed. You will understand why our army’s situation gives me great concern. Timoshenko’s army that broke through near Isium threatens our deep flank south of Charkov. The forces confronting Timoshenko’s army are in no position to withstand another attack. Also northeast of Charkov, near Voltshansk, the danger cannot be excluded. New forces are still not available, so that under these circumstances we would be o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Translator’s Note

- Introduction

- Maps

- Chapter 1: Marching to the Volga

- Chapter 2: The Shattered Attack on the City

- Chapter 3: Counteroffensive and Encirclement

- Chapter 4: Between Hope and Destruction

- Chapter 5: An End to the Horrors

- Chapter 6: New Shores

- Chapter 7: For the New Germany

- Appendix: German Generals Captured at Stalingrad

- Plate Section