- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wellington's Spies

About this book

The gripping story of three intelligence officers whose dangerous work and sacrifice helped lead to victory over Napoleon's forces.

Intelligence was just as important in the Napoleonic Wars as it is today. But back then, there was only one way of obtaining it: through spies and informers. Here, Mary McGrigor uses firsthand accounts of three of Wellington's most daring and successful intelligence officers to reveal the relationships they established and the risks they faced.

The three men, all of Scottish descent, were very different in character, but all showed remarkable courage. Their stories are filled with danger, action, adventure, and even romance—as well as tragedy and narrow escape. Skillfully interwoven against the backdrop of the brutal Peninsula War, in which atrocities were commonplace, this book gives a fresh insight into Wellington's remarkable triumph over Napoleon's armies.

Intelligence was just as important in the Napoleonic Wars as it is today. But back then, there was only one way of obtaining it: through spies and informers. Here, Mary McGrigor uses firsthand accounts of three of Wellington's most daring and successful intelligence officers to reveal the relationships they established and the risks they faced.

The three men, all of Scottish descent, were very different in character, but all showed remarkable courage. Their stories are filled with danger, action, adventure, and even romance—as well as tragedy and narrow escape. Skillfully interwoven against the backdrop of the brutal Peninsula War, in which atrocities were commonplace, this book gives a fresh insight into Wellington's remarkable triumph over Napoleon's armies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART 1

1

THE FIRST CAMPAIGN

THE OCCUPATION OF PORTUGAL NAPOLEON’S BAITED TRAP

August 1808 – January 1809

By the summer of 1808 Napoleon, in a figurative sense, held Europe in the palm of his hand. Prussia and Austria had been overpowered and Russia, through the Treaty of Tilsit, was also under his thrall. England alone stood against him, thanks to her maritime power. The defeat at Trafalgar – largely the fault of Admiral Villeneuve, so Napoleon believed – meant that the survivors of his own fleet, effectually blockaded by the British navy, were no longer a supreme fighting force. His army, on the other hand, was the largest and most superbly trained of any country in the world. Therefore he was confident that the British force, diminutive compared with his own, could be defeated on land.1*

Portugal, England’s oldest ally, was also one of the countries on which she depended for trade. Napoleon believed that, by installing an army of occupation, he could not only close all the ports to the British but also capture the Portuguese fleet. Only one thing forestalled him, namely that to take an army overland into Portugal he must have the acquiescence of Spain. He was, as usual, triumphant. The Treaty of Fontainebleau, which allowed him to take an army through Spain into Portugal, was signed in October 1807.

The Emperor, acting with his usual energy, had the wheels of war in motion while the ink was still barely dry. In less than six weeks Marshal Junot was leading 30,000 men into Lisbon. Almost as they entered the city, the Portuguese royal family, escorted by the British navy, were sailing from the mouth of the Tagus on their way to exile in Brazil.

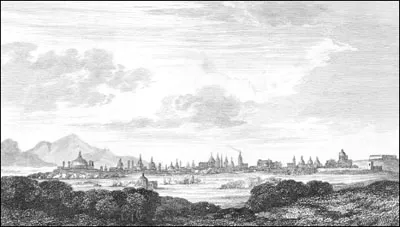

MADRID

Napoleon could congratulate himself on achieving a coup d’état. However, with increasing arrogance, he then overplayed his hand. The Spanish had promised him freedom of transit through their country. Now, claiming it to be essential to the maintenance of his army in Portugal, he annexed several key fortresses which he garrisoned with French troops. The Spanish people, realizing at that point that, thanks to their leaders, they would soon become a subject state, rose in rebellion on the ‘Dos de Mayo’, 2 May 1808. Manuel de Godoy, held responsible for the domination of the French, was forced to resign, while the King, Charles IV, also compliant to the liaison, was compelled to abdicate in favour of his son Ferdinand.

Events then escalated. Napoleon occupied Madrid. The Spanish Kings, both Charles and Ferdinand, were forcibly removed to France, whereupon Napoleon, convinced of his omnipotence, installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain. Both Spain and Portugal rose in arms against the usurper. The War of Independence had begun.

Spanish envoys were sent to London where a treaty of alliance between Great Britain and Spain was signed. Thanks to a fortunate but unforeseen circumstance, a force of 9,500 men, originally destined for an expedition against her colonies in South America, was now available to be sent instead to Spain’s assistance. Sir Arthur Wellesley, already distinguished for his service in India, was directed to take command of this and of another smaller force, of about 5,000 men, commanded by Major-General Sir Brent Spencer, at that time quartered in Gibraltar.

While the British army was assembling, the Spanish were mauling the French. Besieged garrisons defied them and, more significantly, General Dupont, sent to occupy Andalusia, was defeated by the clever strategy of the Spanish General Castaños, at Baylen, on 19 July. Napoleon raged in exasperation, while his brother Joseph, the newly-made monarch, retreated from Madrid to a safer position north of the River Ebro.

Sir Arthur Wellesley sailed from Cork in the frigate Crocodile to land initially at Corunna, on the north-west tip of Spain, on 20 July. The Galician Junta then informed him that no troops were needed. They wanted only arms and gold. Fortunately at that moment an English frigate appeared in the harbour carrying the then enormous sum of two hundred thousand pounds.

Wellesley therefore sailed on to the mouth of the Mondego on the west coast of Portugal where, on 1 August, he landed unopposed. Here, five days later, he was joined by General Spencer, who with his five thousand men, had come from Gibraltar via the Spanish port of Cadiz.

* See Notes pp. 258–261.

2

SEARCHING FOR INTELLIGENCE

So little was known of Spain that British officers were sent to the northern provinces both to report on the state of the country and to confer with the Spanish commanders as to the means of organizing resistance against the occupying French. Among them was Major-General Sir James Leith, a Scotsman from Aberdeenshire, who was ordered to proceed to Santander to report on the state of the armaments in the Asturias, Guipuzcoa and Las Montañas de Santander. With him, as his aide-de-camp, went his nephew, Andrew Leith-Hay, a young man of twenty–three, whose talent as an artist could now be put to good use. Sailing from Portsmouth aboard the Peruvian brig of war, on the evening of 17 August 1808, they sighted the coast of Spain on the morning of the 22nd.

Andrew Leith-Hay was immediately impressed by the magnificence of the country which gradually grew in sight.

‘As the vessel approached the land the mountains of Asturias appeared in the distance, the wild and varied country, wooded to its summits, exhibiting scenery of striking grandeur and interest.’

Arriving in Santander, they met the bishop, who was regent of the province of Las Montañas. General Leith had been told to question him as to the state of the organization and supply of the armies collecting in the northern provinces to oppose the French. The Condé de Villa Neuva was general-in-chief of the province, being a former officer of the Spanish Guards.

Surprisingly, neither the bishop nor the Condé had any real idea of the situation and movements of the enemy, to the point where they could not say. with any certainty that a Spanish force even existed between the French army and Santander.

The main route from the port of Santander, on the northern coast of Spain, to the interior of the country led through Reinosa and thence by Burgos to Madrid. Because news of what was happening in those areas was of such great importance to the British commanders, Andrew Leith-Hay was sent to reconnoitre.’

His protests that, after only three days in the country, he knew not a word of the language were totally ignored by his uncle. The boy had to go and that was that.

My instructions were to proceed by the pass of Escudo to Reinosa, where it was conjectured I should find General Ballesteros (afterwards so distinguished in the Peninsular War) in command of a body of the Asturians. I was to be accompanied by a Spanish captain of the name of Villardet, twelve soldiers of the regiment of Laredo, to which he belonged, and an old man who was to act as an interpreter.

His description of what happened thereafter was hilarious, as he so aptly describes:

The assembling of this formidable cavalcade occasioned a considerable sensation in the town of Santander, and, although late in the evening, a crowd collected to witness our departure. A large and handsome black horse bore the person of the Spanish captain, who was enveloped in his cloak and whose lank and sallow visage was surmounted by a hat of no ordinary dimensions. A mule, caparisoned with all the usual encumbrance of Spanish saddlery, was prepared for me; and as, for the first time, a pair of horse pistols graced my saddle bow, and a cortège appeared to accompany me, I mounted with exultation and derived no ordinary satisfaction from the feeling that I was the hero of this great expedition.

In the midst of these preparations for departure, an incident of ludicrous description rather lessened the importance and detracted from the gravity of the occasion. When the old interpreter proceeded to mount the mule destined to transport him, the solemnity and silence of the scene was suddenly exchanged for the most discordant noise and the most calamitous disturbance. The master of languages, who apparently had neglected the study of equitation, unfortunately for him, had been provided with the only vicious mule in company, which, the moment he ascertained the burden that was intended for him, proceeded with his heels to disperse the crowd, to the terror and annoyance of some, and the amusement of others; nor did he desist from this violent exercise until he had prostrated his rider in the street. [Eventually] the interpreter being mounted upon a more tractable animal, we proceeded on our journey.

After travelling for fifteen miles in increasing darkness they finally arrived at a village where the muleteers insisted they stop for ‘refreshment both for themselves and their quadrupeds’. Unfortunately the posada, or inn, like most others in northern Spain, proved to be primitive in the extreme: the main part of the house being used as a stable for both the horses and the mules.

At daybreak they set off again, travelling through very beautiful country. The road ran through narrow valleys, bounded by hills which were covered to the summits by tall and magnificent trees. Only occasionally, where the valleys opened out onto flatter ground, did the land become cultivated.

Shortly they met a party of the Spanish peasants, volunteers in defence of their country, who already were notorious for their brutal treatment of French prisoners.

In the course of the forenoon we perceived smoke ascending from a wood in our front and, upon arriving at it, found an advanced post of three hundred Asturians, all peasants, who had recently enrolled themselves and were but indifferently armed.

From the commandant I learned that General Ballesteros was at Reinosa, and having travelled as expeditiously as the nature of my escort would permit, reached his quarters in the evening.

General Fransisco Ballesteros, to all outward appearances, was a man destined for fame. A native of Asturia aged only thirty-eight, he had gained rapid promotion, from subaltern to major-general, since the start of the war against France. Andrew described him as superior to any of the other officers whom he had so far come across in Spain.

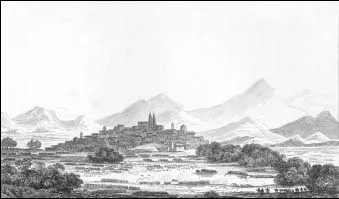

VITORIA

Young, active and intelligent, he at once impressed a stranger with the idea that he was an efficient, and likely to become a distinguished, officer.

By the time of their meeting Ballesteros had been for some time at Reinosa in command of a force consisting of about four to five thousand of his native Asturians who, at that point, had not been with either of the two Spanish armies. He gave Andrew a detailed description of all the information which he had acquired of the positions and movements of the enemy’s troops. The French headquarters was in Vitoria and, to the best of his knowledge, nothing so far had indicated that an immediate offensive would take place. ‘ No force of any description had approached Reinosa and his situation there appeared to be, for the present, secure and undisturbed.’

Andrew, on receiving the assurance that Santander was in no immediate danger, decided he must return immediately to impart this knowledge to his uncle. Thus, having hired post horses, he galloped at midnight through the streets of Reinosa led by a Spanish postillion.

The stillness of a beautiful night was interrupted only by the challenge of the Spanish sentinels as we passed their several posts, and enlivened by the sound of the bells attached to the bridle of my companion’s horse; the wild song in which he occasionally indulged, the distant noise, the mirth of travelling muleteers, and the rush of waters falling over their rocky channels in the ravines and closely wooded valleys through which the road is conducted.

The only pace the Spanish horse ever attempts is either a walk or a gallop, and as the postillion invariably precedes the traveller, the transition from the rapid to the slow pace is attended with a species of shock not agreeable to the person unprepared for this mode of proceeding. Notwithstanding this, riding post in Spain is, upon the great routes where the horses are good, a pleasant and tolerably expeditious mode of performing a journey.

In view of Andrew’s report General Leith decided that, at least for the time being, disturbance in the province of Las Montañas was unlikely to occur. Therefore, together with Andrew, he re-embarked to sail for Gijon and march down to Oviedo. The Bay of Gijon, one of the most exposed on the north coast of Spain, receives the full force of the swell rolling in from the Bay of Biscay. Fortunately, in late August, it was calm. Andrew and the General were lodged in the château of a nobleman, which, although outwardly magnificent, was, like many such buildings, sadly dilapidated, The huge rooms lacked furniture, weeds grew high in the courtyard and the well was long disused. They stayed there, however, only for one night.

The day after our arrival at Gijon General Miranda and a deputation from the Junta of Asturias came for the purpose of escorting the General to Oviedo, and on the following morning we proceeded to that city. Oviedo, the ancient Ovetum and the capital of Asturias, is situated in a romantic and beautiful valley, surrounded by rich and variegated scenery. The lofty spire of the cathedral forms a conspicuous object, and the background of distant mountain gives importance to the scene.

Their reception was extremely friendly. Amazingly, the Spanish seemed to have forgotten that only three years previously, when still allied to the French, their fleet had been largely destroyed at the Battle of Trafalgar. The members of the provincial Junta, who were assembled to receive General Leith, were headed by General-in-Chief Acevedo, an old man, lethargic and extremely short-sighted. Placed in command of the Asturian contingent. he was just about to set off for the town of Llanes, on the coast, where the new levies were expected to number 10,000 men.

Meanwhile, in Portugal, some fifty miles north of Lisbon, Sir Arthur Wellesley, firstly at Rolica on 17 August 1808 and then at Vimiero on the 21st, had soundly defeated the French army commanded by General Delaborde.

The French, were astounded, deeming it virtually impossible that the troops of their beloved Emperor should be thus overcome. The result was that General Kellerman, on the orders of Marshal Junot, was sent to arrange the armistice which resulted in the Convention of Cintra, signed on the last day of the month.

The terms included the liberation of Portugal, together with the reinforcement of the Spanish army of Estremadura with the four to five thousand Spanish soldiers currently held prisoner on board the vessels in the Tagus. The boundaries were to be be recognized and, most importantly, the French troops, together with their guns and horses, were to be conveyed back to their homeland in British warships, complete with all their possessions including accumulated plunder. The safety of all French residents and their Portuguese adherents was assured and the port of Lisbon declared a haven of neutrality for the Russian fleet.2

Sir Arthur Wellesley, much to his fury, was now superseded in command by the Governor of Gibraltar, General Sir Hew Dalrymple, and Sir Harry Burrard, both of them elderly men. Neither was to serve for long, however, for the terms of the Convention of Cintra so enraged the British that a public enquiry ensued. Subsequently, while Wellesley was cleared of all charges, Sir Hew Dalrymple was dismissed and Burrard forced to retire.

On 4 October 1808 the command of the thirty thousand men in Portugal fell upon Sir John Moore. Now aged forty-seven, Moore, the son of a doctor, had been born in Glasgow in 1761, As a young lieutenant, aged only nineteen, he had first won distinction in the American War of Independence. Then, having served in Corsica, the West Indies, Holland and Egypt, and been wounded no less than three times, he had been placed in command of the south-east of England, where, as Napoleon threatened invasion, he had been behind the building of the Martello towers. Also dur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Maps

- Introduction

- PART 1

- PART 2

- PART 3

- PART 4

- Epilogue

- Source Notes

- Bibliography

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wellington's Spies by Mary McGrigor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.