- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

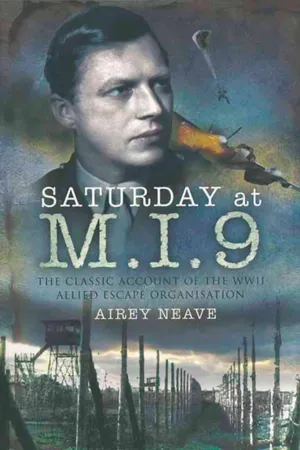

The author of

Flames of Calais details life in the top-secret department of Britain's War Office during World War II in this military memoir.

Airey Neave, who in the last two years of the war was the chief organizer at M.I.9, gives his inside story of the underground escape lines in occupied North-West Europe, which returned over 4,000 Allied servicemen to Britain during the Second World War. He describes how the escape lines began in the first dark days of German occupation and how, until the end of the war, thousands of ordinary men and women made their own contribution to the Allied victory by hiding and feeding men and guiding them to safety.

Neave was the first British POW to make a "home run" from Colditz Castle. On his return, he joined M.I.9 adopting the code name "Saturday." He also served with the Nuremburg War Crimes Tribunal. Tragically Airey Neave's life was cut short by the IRA who assassinated him in 1979 when he was one of Margaret Thatcher's closest political allies.

Praise for Saturday at M.I.9

"There isn't a page in the book which isn't exciting in incident, wise in judgment, and absorbing through its human involvement." — The Times Literary Supplement (UK)

Airey Neave, who in the last two years of the war was the chief organizer at M.I.9, gives his inside story of the underground escape lines in occupied North-West Europe, which returned over 4,000 Allied servicemen to Britain during the Second World War. He describes how the escape lines began in the first dark days of German occupation and how, until the end of the war, thousands of ordinary men and women made their own contribution to the Allied victory by hiding and feeding men and guiding them to safety.

Neave was the first British POW to make a "home run" from Colditz Castle. On his return, he joined M.I.9 adopting the code name "Saturday." He also served with the Nuremburg War Crimes Tribunal. Tragically Airey Neave's life was cut short by the IRA who assassinated him in 1979 when he was one of Margaret Thatcher's closest political allies.

Praise for Saturday at M.I.9

"There isn't a page in the book which isn't exciting in incident, wise in judgment, and absorbing through its human involvement." — The Times Literary Supplement (UK)

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Saturday at M.I.9 by Airey Neave in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

| PART I | AFTER COLDITZ | ||

| 1. | Background to the Escape Lines | ||

| 2. | Prisoner of War | ||

| 3. | Switzerland 1942 | ||

| 4. | Louis Nouveau’s flat | ||

| 5. | The Great Central Hotel | ||

| 6. | Saturday at M.I.9 | ||

| PART II | THE O’LEARY LINE | ||

| 7. | The Pioneers | ||

| 8. | The Return of Whitney Straight | ||

| 9. | Sea Operations | ||

| 10. | The Price | ||

| PART III | THE COMET LINE | ||

| 11. | Dédée | ||

| 12. | The Maréchal Affair | ||

| 13. | A Winter of Disaster | ||

| 14. | Gibraltar Meeting | ||

| PART IV | WOMEN AGENTS | ||

| 15. | Mary Lindell | ||

| 16. | The Commandos | ||

| 17. | Trix | ||

| PART V | BRITTANY | ||

| 18. | Val Williams | ||

| 19. | ‘Shelburne’ | ||

| PART VI | ‘MARATHON’ | ||

| 20. | Before the Bombardment | ||

| 21. | The ‘Sherwood’ Plan | ||

| 22. | The Race to the Forest | ||

| PART VII | OCCUPIED HOLLAND | ||

| 23. | After Arnhem | ||

| 24. | Pegasus I and II | ||

| PART VIII | AFTERMATH | ||

| 25. | The Traitors | ||

| 26. | In Retrospect | ||

AFTER COLDITZ

CHAPTER 1

Background to the Escape Lines

FIFTEEN years ago, I described how, disguised as a German officer, I escaped from Colditz castle near Leipzig, and reached neutral Switzerland in January 1942.1 I wrote of my own reaction to this experience and the vivid contrast of the former prisoner-of-war set in authority over Goering and other Nazi leaders at Nuremburg three years later. Of what happened to me during those three years I said little. I devoted only two cryptic pages to my part in the organisation of secret escape routes by M.I.9 in Europe during the Second World War.

There were two reasons for this gap in my story. In war, the very young are often exposed to violent tensions and only in middle age do these subside. I could not banish from my thoughts the intense emotion of my successful escape from Colditz to England. With the years, this personal adventure became less important to me, and it was easier to write objectively of operations to save others from German prison camps.

The second reason for my veiled references to the escape lines, was the belief, when They Have Their Exits was published, that their structure and techniques might be used again. I wrote the book during a period of extreme hostility between the Soviet Union and the Western world. In the early nineteen-fifties war in Europe seemed possible over the same ground where the Allies had fought Hitler. It was assumed that men and women in countries occupied by the Nazis, who had served us so well, would volunteer a second time and, though stories of individual heroism had appeared in print, that true details of the organisations should remain unpublished.2

Official reticence may be exasperating to those who assert that the secrets of the last war need no longer be kept. But in 1953, it was obvious that the nature of the system in London by which the escape lines were operated should not be disclosed. Even today, all documents and many particulars of M.I.9, the War Office branch concerned with Allied prisoners-of-war, remain subject to the Official Secrets Acts. But with the passage of time I am able, as one of those who took part, to give my personal account of its work in organising the return of Allied Servicemen.

My three years with M.I.9 were concerned with secret escape operations in France, Belgium and Holland and they are the subject of this book. I played no part in similar activities in Italy and the Middle and Far East. I seek to record how these lines were assisted from London and the courage and sacrifice of ordinary people who volunteered to help fighting men return to action against the enemy. Those who took part in this perilous work were of every age, from the very young who acted as guides, to the old and poor who hid men on the run in defiance of the Gestapo.

By the end of the war this form of clandestine service had become a popular movement in which large numbers of men and women of different backgrounds and political beliefs made their contribution to victory. Harbouring men shot down in air combat or cut off from their regiments, appealed to their humanity. They did not regard themselves as spies, nor were the escape organisations, except rarely, concerned with military intelligence or sabotage. Until the end of the war, there were few trained agents of M.I.9 in the field. The organisation depended on several thousand volunteers to contact the men and hide them till they could be brought to safety. The function of M.I.9 was to supply money, radio communications, the dropping of supplies, ‘pickups’ by aircraft and naval evacuations from the coasts of France.

The escape lines had few of the political complications which beset other secret services. Communists and priests could combine in what they believed to be a great human cause. It inspired doctors and nurses, artists and poets, to risk their lives. The characters in this story were their leaders but the majority came from lowly cafés, farms and working-class homes in all corners of occupied North-West Europe. At the end of the war M.I.9 estimated that there were over 12,000 survivors of this movement, but few realise the value and significance of their work today. Those who never experienced Nazi occupation may find it difficult to understand their enthusiasm, their mistakes and their extraordinary persistence in the face of treachery and the Gestapo. The survivors of that terror seek neither publicity nor to point a moral to a younger generation. They hated Nazi tyranny and acted in the name of charity and freedom. They wished, too, to play their part, however humble, in the Allied struggle.

The post-Dunkirk period in North-West Europe set the scene for future underground escape operations. By the Armistice of June 1940, France was divided by a demarcation line. All the country north and west of the line was occupied by German Troops.1 South of it was the Free or Unoccupied Zone administered by the Government of eighty-five-year-old Marshal Petain from Vichy. It was known, and is referred to here, as the Vichy Government. Though hostile to Britain and her allies, it lacked the authority to prevent the establishment of large-scale escape activities after Dunkirk until the Occupation by the Germans of the whole of France in November 1942.

In Occupied France, the rule of the Gestapo and other German counter-espionage services, made the running of escape routes a dangerous operation from the start, and there were early casualties. In the Unoccupied Zone, the security forces consisted of the gendarmes of French civilian police who frequently co-operated with escape workers and the hated Milice, a group of thugs recruited by the Vichy Government who often betrayed and arrested their own countrymen. They have been described as sadists drawn from the scum of the jails and a constant threat to the French Resistance Movement.2

The first escape organisations were formed by small groups of patriots in 1940, without money or outside aid, to enable survivors of the British Army and Air Force to avoid being taken prisoner by the Germans after Dunkirk. Several hundred drifted through France in groups or as individuals. Those who were not rounded up by the Germans crossed the demarcation line to the Unoccupied Zone and waited at Marseille for someone to take charge of them. Many of those who helped were nurses who spirited them out of hospital in northern France, hid them with friends and sent them on their way to Paris. For a few weeks after the armistice, many got through to the relative security of the south coast without papers or speaking a word of French, and sometimes in uniform. Soon such journeys became almost impossible without guides. French and Belgians determined to resist Hitler, began to organise themselves into teams to hide and shelter them, but it was not until 1941 that regular escape lines from Brussels, Paris and Marseille to neutral Spain were fully established. By then, the Gestapo had gained full control in occupied France and infiltrated their agents in civilian clothes south of the demarcation line.

June and July 1940 were romantic months in the history of escape. Soldiers who had lost touch with their units but were still free, settled down with French families in the north of France and were reluctant to leave. A few married, and remained there till the war was over. Others, accompanied by French and Belgian girls, walked or bicycled in the fine weather, from village to village, till they reached the Unoccupied Zone. The Germans, busy with the problems of occupation and the projected assault on England, caught few of them. Several weeks after the fall of France, bewildered figures in khaki battle dress could still be seen in the streets of Paris. On the French Riviera a committee of British residents, with the Duke of Westminster as Chairman, was formed to raise funds for those who were assembling on the coast with few ideas of how to rejoin their lines. The more determined, led by their officers, crossed the Spanish frontier, and, after experiencing the squalor of Spanish prisons, were released to the British Embassy in Madrid. A private soldier, on arrival in diplomatic hands, anxiously explained:

“I’ve lost me bloody rifle, sir!”

Throughout 1940 and 1941, organised escape routes took shape under leaders whose names were to become famous in the history of underground war. They have been portrayed in a number of books published in the last twenty years. The story of Captain Ian Garrow and Pat O’Leary at Marseille has been told by Vincent Brome in The Way Back.1 ‘Rémy’ the great French Resistance leader, has compiled three volumes of interviews with the survivors of the Comet line founded by Andrée De Jongh (Dédée) and her father in 1941.1 I have written an account of her and the Comet escape line in Little Cyclone.2 To this period also belongs the story of Mary Lindell in No Drums No Trumpets by Barry Wynne.3 These books reveal the atmosphere in which early escapes from the Germans were organised, and they are stories of splendid personal exploits, suffering and triumph. They convey only a shadowy impression of the organisation in London which kept in contact with their leaders. This was the top-secret secti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright Page

- Contents