- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

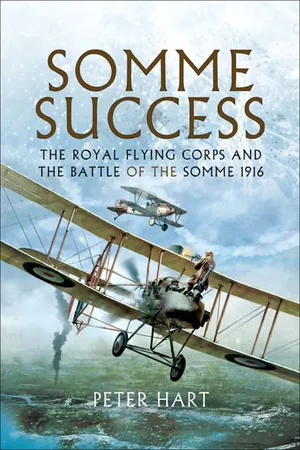

This history of the Royal Flying Corps during the Battle of Somme offers a comprehensive firsthand look at WWI military aviation.

During the summer and fall of 1916, high above the blood-soaked trenches of the Somme, the Royal Flying Corps was engaging in one of the first great aerial battles of history. Even in those pioneering days of aerial warfare, primitive aircraft and the brave men who flew them were proving vital. Before the battle, photographic reconnaissance aircraft from both sides were desperately trying to map the opposition's deployment; artillery spotting aircraft were locating hidden targets; and bombing raids had become standard.

Somme Success provides a detailed description of all facets of air operations of the period using the firsthand accounts of those who were there. It describes how the Royal Flying Corps answered the Fokker scourge in Airco DH.2 single-seater planes and, later, the ubiquitous F.E.2b two-seaters—the plane that shot down German 'Ace' Max Immelmann.

Having conceded air supremacy to the Royal Flying Corps early in the Somme Offensive, the German Air Service launched an aerial counterattack during August and September. The Albatross single-seaters of the elite scout squadron proved superior to any allied aircraft. When German fighter pilot Manfred von Richthofen—the Red Baron—took to the skies, a new period of German supremacy began.

During the summer and fall of 1916, high above the blood-soaked trenches of the Somme, the Royal Flying Corps was engaging in one of the first great aerial battles of history. Even in those pioneering days of aerial warfare, primitive aircraft and the brave men who flew them were proving vital. Before the battle, photographic reconnaissance aircraft from both sides were desperately trying to map the opposition's deployment; artillery spotting aircraft were locating hidden targets; and bombing raids had become standard.

Somme Success provides a detailed description of all facets of air operations of the period using the firsthand accounts of those who were there. It describes how the Royal Flying Corps answered the Fokker scourge in Airco DH.2 single-seater planes and, later, the ubiquitous F.E.2b two-seaters—the plane that shot down German 'Ace' Max Immelmann.

Having conceded air supremacy to the Royal Flying Corps early in the Somme Offensive, the German Air Service launched an aerial counterattack during August and September. The Albatross single-seaters of the elite scout squadron proved superior to any allied aircraft. When German fighter pilot Manfred von Richthofen—the Red Baron—took to the skies, a new period of German supremacy began.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Somme Success by Peter Hart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

In the Beginning...

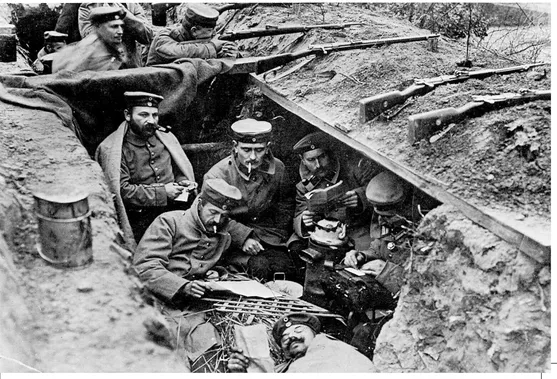

In the beginning there was the ground war. The entrenched armies faced each other across No Man’s Land all along the Western Front; an inviolable line that marked the end of the brief period of open warfare in 1914. As the armies crashed into each other the soldiers scratched themselves impromptu cover when it seemed certain death to stay above ground. They sought sanctuary from the streams of machine gun bullets and crashing detonations of artillery shells that typified modern warfare. Gradually these tentative scrapings were deepened and extended until an unbroken front was created from which they could pour fire into any attack made upon them. So the line froze into immobility. Gradually a second or third line was dug and the whole system interconnected with communication trenches that allowed the troops to come into the line without ever raising their heads above the trench parapets. At first both sides were relatively confident that these trenches were temporary resting places, while they girded their metaphorical loins for the next great attack that would surely rupture the enemy’s line, allowing a resumption of old style open warfare, culminating in an enjoyably satisfying advance to victory in Berlin or Paris depending on perspective. However, for all their initial optimism, it was an intractable problem that faced the generals in 1915 and their pre-war experience was to prove of little or no value.

German troops relaxing in a shallow trench.

There was another new factor. Though before the war the military value of the aeroplane had been clearly recognized, the first powered flight by the Wright brothers had only taken place eleven years earlier in 1903. Aircraft were developing rapidly, but their limitations in 1914 were considerable. Speeds were dangerously low and the margin between safe flying and stalling speed was often extremely narrow. Although some aircraft had flown at over 100mph the bulk of aircraft flew at between 60 and 80mph. Methods of controlling movement in the air were not fully understood and consequently aerial manoeuvres were often carried out on the basis of guesswork; simply repeating actions that had not actually resulted in disaster last time they were tried. The science of aeronautics was literally in its infancy. Underpowered as they were, the amount of weight that each aircraft could lift was severely limited and this hindered any attempt to develop any real military ‘strike’ role by deploying bombs or machine guns. The immediate practical military interest in the aircraft centred on the obvious possibilities of aerial reconnaissance. Aircraft offered the embattled general the opportunity for observers to rise above the confusion of battle and gain access to the minutiae of his opponent’s dispositions and movements. Reams of vital intelligence could be harvested at the risk of just a few daring aviators flying deep into enemy territory, rather than the much more limited results offered by the conventional reconnaissance in force by cavalry. Although the Great Powers invested to some degree in aircraft before the war, rigid airships were seen by many as a far more promising method of pursuing aerial warfare. Not only did airships have a far greater range of operations, but they could also lift significant bomb loads, with which to hopefully destroy their enemies when they found them.

By 1912 the military was showing a keen interest in aviation; here British Army Aeroplane model No.1, designed by Samuel Cody, is being wheeled out for a test flight. The classic aircraft shape had yet to emerge.

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had gone to war under the command of Sir David Henderson with just four squadrons, that in all totalled some 63 serviceable aircraft. The primitive state of aircraft technology can be judged by the fact that it was still considered a remarkable feat that they had managed to cross the English Channel under their own power. After all, the first successful cross-Channel flight by the redoubtable Louis Blériot had only been completed five years previously. Once there, the RFC soon proved its value by helping to expose the workings of the German Schlieffen plan to the initially sceptical British Commander in Chief Sir John French. It was their reconnaissance reports that provided a basis for the Allied reorganization and counter-attack at the Battle of the Marne.

The most crucial advances in aerial warfare were made incredibly early in the war. Aerial photo-reconnaissance began on 15 September with a mission undertaken by Lieutenant G F Pretyman above the emerging German trenches in the Aisne hills which had blocked the Allied advance. Aerial photography greatly expanded the reconnaissance capabilities of aircraft. The plates exposed could be examined when developed safely back on the ground and so the science of photographic interpretation was born as the slightest traces of German activity could be exposed to the camera in the sky. At the same time the first wirelesses were carried into the sky where they provided aerial observation that allowed the British artillery to range onto targets invisible to their ground level forward observation posts. Thus, just a month after the RFC had landed in France their two most important roles in the First World War had been defined and refined. In addition small bombs, had been carried into the air to attack targets of opportunity such as columns of troops. Meanwhile the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), which was the Royal Navy equivalent of the RFC, had begun to experiment in ‘strategic’ bombing raids on Zeppelin sheds, naval bases and even German towns. Small-scale and ineffectual they may have been in the context of later events, but the first steps had been taken that would lead in time to the wholesale devastation of cities from the air.

However, it was equally apparent that their German opposite numbers were performing the same function - the curtain had been lifted for both sides. It was obvious that a great advantage would be gained by blinding the aerial eyes of the opposing forces. Thus, although they were hamstrung by the weakness of their aircraft, right from the start aviators harboured murderous designs against each other. Observers carried rifles or shotguns and they exchanged fire with their counterparts wherever possible. The sheer difficulty of aiming at a relatively fast-moving target with a single shot weapon meant that casualties from enemy action were rare in the opening months of the war. Efforts to carry the light Lewis machine gun into the air floundered because even the extra weight crippled the performance of the aircraft. Seemingly, you could have speed and altitude, or a machine gun, but not both. Nevertheless the first German aircraft were forced down just two days after the Battle of Mons; the first British pilot to be wounded in combat with a German aircraft was Lieutenant G W Mapplebeck on 22 September; while the French scored the first real aerial victory when a Voison shot down a German Aviatik on 5 October.

Although few aviators were killed directly by enemy action, the multifarious dangers of flying caused a constant haemorrhaging of men and machines in accidents. At the front the RFC was withering away, but their importance had been officially recognized. A rapid expansion was ordered by the Minister of War, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, to achieve a target of some 100 squadrons. Unfortunately, this was far easier envisaged than carried out. Britain did not have an aeronautics manufacturing industry that could suddenly turn on the tap to build the hundreds of aircraft that would be required. Pilots, observers and ground mechanics were also in scarce supply and their training would take time. To simplify matters all round, it was decided early on to concentrate on producing just one aircraft as the workhorse for most of these putative squadrons. Because of the time it took to build the aircraft and train the pilots it was to be this decision, taken in 1914, that would decide what machines the pilots in 1915 and 1916 fought in. The choice settled on the BE2 C.

The BE2 C was a variant of the ‘Blériot Experimental’ series of all-purpose tractor aeroplanes (the engine was at the front of the aircraft) designed in sequence from the BE1 at the Royal Aircraft Factory, (RAF) Farnborough. It had many advantages as a photographic reconnaissance and artillery observation aircraft in that it was designed to be inherently stable. In this it was remarkably successful as once aloft it could almost fly itself. The aircraft were powered by the new RAF 1 90hp engine that generated a flying speed of 72mph at 6,500 feet and 69mph at its service ceiling of 10,000 feet, although it took a lamentable 45 minutes to reach that height. Production was bedevilled by frequent design modifications and the difficulties inherent in placing contracts with firms that in some cases had never before built aircraft of any type. Nevertheless, the BE2 C was reaching the front in ever increasing quantities by mid-1915. Here it proved a safe flying machine that would provide yeoman service in its designed role. Unfortunately it had one serious flaw that would become apparent as the air war developed that year - it was not, and never would be an effective aircraft for the rigours of aerial combat.

The BE2 C was the workhorse of the RFC in the first three years of the war. IWM Q 56847

It was recognised that pilots had got to be trained quickly and would not have a great deal of experience and so an aircraft was needed which would be simple to fly and between them they produced the BE2 C. The BE2 C was the first aircraft that was to be really inherently stable. The dihedral on the wings gave it lateral stability; the dihedral at which the tail plane was set in relation to the main planes gave it fore and aft stability. The lateral stability was very strong indeed – it would correct anything by itself. A very stable aircraft. From the flying point of view this had the very great disadvantage that as the machine wanted to stay on a level keel, right way up, it was very difficult to make it do anything else.1 Lieutenant Charles Chabot, 4 Squadron, RFC

The problems of trench warfare that both sides faced were a direct consequence of the application of the industrial might of nation states to the process of war. The mass production of rifles, machine guns and artillery for the use of citizen armies numbering millions took the whole business of war to a new pitch. To launch a successful attack the infantry had to first cross an area covered by long-range enemy artillery. Units could be devastated before they even reached the front line. Once in their ‘jumping off trenches’ they remained vulnerable to shell fire until the whistles blew for Zero Hour. At this point they had to leave all cover and venture across a No Man’s Land swept by bursting shells, the deadly stutter of machine guns and concentrated rifle fire. When they got near their enemies they were baulked by an impenetrable wall of barbed wire. The obvious answer to the conundrum lay in their own artillery. It could destroy, or at least suppress the enemy artillery batteries; smash the machine gun posts; flatten the trenches; kill the front line garrison and blast apart the barbed wire defences. Unfortunately there were problems in this theoretical approach. It pre-supposed the enemy would do nothing, but of course they too concentrated their guns in the disputed area and inevitably every battle became a huge artillery duel. Pinpoint accuracy was essential to destroy reinforced earthwork defences, but the science of gunnery was not well advanced enough to secure precision gunnery. The only alternative lay in deluges of shells to annihilate everything in the target area, but such wasteful practices were effectively debarred by the crippling shortages of modern guns, shells and trained gunners.

The first British attempt to break out of the strait jacket of trench warfare was made by the First Army commanded by General Sir Douglas Haig in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle launched on 10 March 1915. Haig built the pioneering work of the RFC into his overall plan and relied on the artillery using aerial observation to overcome the identified German batteries and German strongpoints. The RFC produced a photographic map of the whole of the German defensive trench system. Some of the technical pr...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Prelude

- Preface

- Chapter One - In the Beginning...

- Chapter Two - An Aerial Offensive

- Chapter Three - A Perfect Summer Day

- Chapter Four - July: Masters of the Air

- Chapter Five - August: The Fight Goes On

- Chapter Six - September: The Tide Turns

- Chapter Seven - October: Clinging on...

- Chapter Eight - November: Full Circle

- Bibliography of Quoted Sources