- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For a hundred years, British and Chinese territorial claims in the Himalayas conflicted, with Indian historians claiming that the region was the fountainhead of Hindu civilization. In the halcyon days of the Raj, London saw Afghanistan and Tibet as buffers against Russian and Chinese imperialism. In 1913, an ephemeral agreement between Britain, Tibet and China was signed, recognizing the McMahon Line as the border of the disputed territory. China, however, failed to ratify the agreement, while India protested against a loss of historical land.After the Second World War, India became independent of Britain and Chinese Communists proclaimed a peoples republic. Despite cordial overtures from Indian Prime Minister Nehru, in late 1950 the Chinese Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) invaded Tibet. In the ensuing twelve years, Indian diplomacy and Chinese cartographic aggression were punctuated by border incidents, particularly in 1953 when armed clashes precipitated a significant increase in the disposition of troops by both sides. In the spring of 1962, Indian forces flooded into the Ladakh region of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, to check the Chinese.In a spiralling game of brinkmanship, in September, ground forces were strategically deployed and redeployed. On 10 October, thirty-three Chinese died in a firefight near Dhola.Embittered by Moscows support of India against a sister communist state, and in a bid to clip Nehrus belligerent wings, on 20 October, the PLA launched a two-pronged attack against Indian positions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sino-Indian War by Gerry van Tonder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. DEFENCE OF THE REALM

The Sino-Indian border dispute, unlike most others, owes much to its past. Fundamental factors underlying the dispute can be traced back to post-Second World War independent India and Communist China. Prior to this, nearly a hundred years of competition between imperial Britain and China, and previous centuries that saw military expeditions across the Himalayan mountains as early as 647 AD, contributed to the tensions. Doyens of Indian history date their country’s cultural claim to the Himalaya as far back as 1500 BC, the fountainhead of Hindu civilization. The Chinese would have no trouble delving even further back into their dynastical annals for similar supporting evidence.

Historically, the ancient kingdom of Tibet has always been the theatre of Sino-Indian confrontation. As Victorian Britain consolidated its tenure over the Indian subcontinent during the latter half of the nineteenth century, it increasingly began to look at the sprawling and heavily populated nation’s northern frontiers. The integrity of the British Raj was dependent on Whitehall instruments of security policies that, over time, had evolved into the absolute importance of Tibet to the northeast and Afghanistan to the northwest as buffers against any threat from Manchurian China and Czarist Russia.

China’s rulers had always claimed dominion over Tibet to a lesser or greater extent, depending on the level to which China’s regional power waxed and waned. As the power of the Manchu dynasty began to disintegrate toward the end of the nineteenth century, China’s role of overlord in Tibet became nominally titular. London was quick to exploit the vacuum, seizing the opportunity to actively pursue a ‘forward policy’ which ultimately extended India’s sphere of influence as far as the religious and administrative Tibetan capital, Lhasa. With the demise of the Manchu regime and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, Peking was unable to reassert its control over Tibet.

Britain’s determination to secure the Tibetan frontier peaked the following year when London sponsored a tripartite conference at Simla (now Shimla), a mountain resort and the largest city in the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. It is bordered by Jammu and Kashmir to the north, Punjab and Chandigarh on the west, and Tibet to the east. Plenipotentiaries from Britain, China and Tibet met to negotiate an agreement that would define Tibet’s political status in relation to China and India. The British hoped to conclude an agreement that would be the culmination of a series of treaties it had already signed with the Himalayan border states such as Sikkim and Burma and, in so doing, establish Britain as the dominant power in the region.

Today, the Simla conference is chiefly remembered for the establishment of the McMahon Line, the boundary drawn on the conference map to delineate the frontier between India and Tibet from Bhutan eastward, to Burma. Named after the British plenipotentiary to Simla, Sir Henry McMahon, who introduced the initiative, the line would follow the crest ridge of the Great Himalayan range as the natural Indo-Tibetan boundary. However, and through either indifference or ignorance, the line was drawn on a small-scale map, giving only a rough and ill-defined indication of the actual border. The Himalayan crest along this northeast sector is broken in a number of places by river gorges and bisecting ranges, and was, as yet, largely terra incognita.

However, the proposed division of Tibet into two distinct regions, to be known as Inner and Outer Tibet, proved contentious and divisive. Under such a political delineation, Peking’s authority would be limited to those areas of Tibet bordering on China’s southwestern provinces, while ‘Outer’ Tibet, which would include Lhasa and all of western Tibet, would be granted full autonomy status.

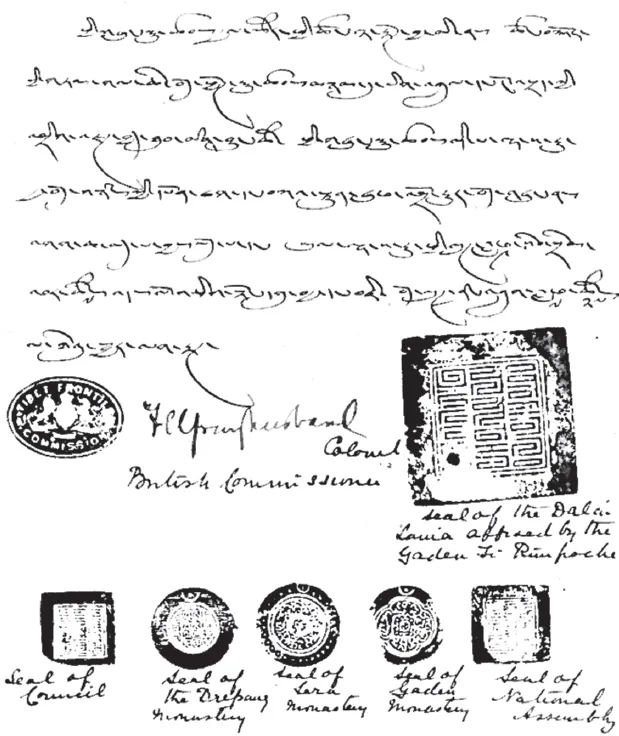

Although its plenipotentiary had initialled the draft convention at Simla, signifying acceptance, the Chinese government refused to sign or be party to the treaty. Peking’s objections referred to the proposed boundary between Inner and Outer Tibet only. It was apparent at the time that the McMahon Line dividing India and Tibet was not challenged by China.

In July 1914, the British and Tibetan delegates, in the absence of the Chinese member, unilaterally signed the Simla Convention. At Delhi in March that year, Britain and Tibet had already endorsed notes and a map delineating the McMahon Line in greater detail.

With the outbreak of the First World War, the spotlight on the Tibetan issue waned sharply as Britain and her allies were forced to divert their attentions to far more pressing issues, particularly in Europe. Ignoring the absence of a Chinese signature to the Simla Convention, London let it officially be known that it considered the Simla accords to be equally binding on the three governments concerned.

Convention between Great Britain and China over Tibet, 1906.

During the interwar years, the Tibetan issue remained largely dormant. Lhasa enjoyed its state of de facto autonomy, while border security gave New Delhi little cause for concern. With the arrival of the invading Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria in September 1931, the Nationalist Chinese government tried to reassert Chinese influence in Tibet in 1933 and 1938, but these advances from Peking were spurned by the Tibetan authorities.

From late 1948, the newly independent India displayed cordial feelings toward the Chinese Communists as they also entered a new phase of national sovereignty. However, this state of good neighbourliness was rudely shattered when 40,000 troops of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army crossed the Tibetan border at Chamdo in October 1950. Surrounding the outnumbered Tibetan forces and capturing the town, the PLA ceased hostilities. A message was conveyed to Lhasa inviting representatives of the Dalai Lama to Beijing to negotiate a new Chinese-controlled status for the mountain kingdom.

On 23 May 1951, the seventeen-point ‘Agreement of the Central People’s Government and the Local Government of Tibet on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet’ was signed in Beijing, facilitating the Tibetan people to “return to the family of the Motherland the People’s Republic of China (PRC)”. That October, the Dalai Lama formally acquiesced to Chinese suzerainty in a telegram to Beijing:

The Tibet Local Government as well as the ecclesiastic and secular people unanimously support this agreement, and under the leadership of Chairman Mao and the Central People’s Government, will actively support the People’s Liberation Army in Tibet to consolidate national defence, drive out imperialist influences from Tibet and safeguard the unification of the territory and the sovereignty of the Motherland.

Seemingly overnight, the territorial integrity of India’s Himalayan frontier had again become a major problem, but this time it would no longer be a British colonial issue, but one for fledgling Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru would come to regard the Chinese ‘liberation’ of Tibet in 1950/51 as the catalyst of his dispute with Beijing. Against a backdrop of an alarmed legislature, for the first time Nehru invoked the controversial McMahon Line and the Himalayan crest range as “India’s magnificent frontier” as the irrefutable, and therefore inalienable, Sino-Indian border.

New Delhi began gradually taking constrained steps in strengthening its armed forces in the frontier regions, Nehru preferring to focus his attention on diplomatic solutions. During 1950/51, he sought guarantees from Beijing that Tibet’s autonomy would be respected. By 1952, India had signed new accords with the buffer states of Bhutan, Sikkim and Nepal, aimed primarily at securing these strategic states within its sphere of influence. Further pursuing his desire for a peaceful, diplomatic resolution to the frontier issues with Beijing, Nehru also pressured Beijing for an agreement that would regularize his country’s commercial and cultural ties with Tibet.

The much-vaunted Sino-Indian ‘Panch Shila’ (from Sanskrit panch: five, sheel: virtues), signed on 29 April 1954, was the desired outcome, in which India recognized China’s sovereignty over “the Tibet region of China”. Incorporating the so-called Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, entreating non-interference in others’ internal affairs and respect for each other’s territorial unity integrity and sovereignty. In hindsight, perhaps it was naïve of Nehru at the Asian Prime Ministers Conference in Colombo, Ceylon—only days after the signing—to state: “If these principles were recognized in the mutual relations of all countries, then indeed there would hardly be any conflict and certainly no war.”

In 1953, Beijing subtly embarked on psychological ‘cartographic aggression’. New Chinese maps were periodically produced in the communist state, clearly showing the disputed border areas as territorially falling within China. New Delhi lodged formal protests, but the Chinese defended their actions by saying that they were merely reproducing Nationalist Chinese maps so that any future changes would be based on informed decisions derived from surveys and collaboration with its neighbours.

New Delhi, guided by the fifth of the Panch Shila principles, advocating ‘peaceful co-existence’, tried to downplay the ominous significance of these territorial differences, albeit that within certain influential Indian political circles there was growing disquiet that a potentially major border dispute was looming.

In late 1957, these concerns grew considerably when New Delhi discovered, to its chagrin, that the Chinese had constructed a road bisecting the northeastern corner of the Indian-claimed region of Ladakh, the Aksai Chin, an inhospitable, barren plateau never included in New Delhi’s administration. A clandestine military team deployed in the spring of 1958 to reconnoitre the disputed area was captured by a Chinese patrol in what would be the first major frontier incident. For more than a year, both China and India kept the whole incident under wraps until the autumn of 1959 when armed clashes on the northeast frontier, as well as in Ladakh, dramatically pushed the border dispute into the public domain.

The 1959 clashes, a consequence of Beijing’s quashing of the Tibetan revolt during the spring of that year, resulted in a significant escalation in official and public rhetoric and antagonism between China and India. With the Dalai Lama fleeing Lhasa into exile in India in March, the Chinese bolstered their troop strengths in Tibet, occupying the Himalayan border passes in an effort to stem the flow of Tibetan refugees, while guarding against an ingression of war matériel and Tibetan resistance fighters.

“WE WILL DEFEND OUR FRONTIERS”—Mr. Nehru

Parliament Told of Chinese Attacks

Mr. Nehru, the Prime Minister, told Parliament in New Delhi yesterday that India had put the army in control of the entire sprawling 35,000 square-mile North-East Frontier Agency, where the Chinese had committed aggression from Tibet. There had been firing “for a considerable time,” he said. An outpost had been almost encircled in the Subansiri area and had run short of ammunition. Subsequently the Indians withdrew from the outpost.

In the tumultuous atmosphere of the House, Mr. Nehru was at first understood to have said that fighting was still continuing, but the official text of his statement available later made it clear that this was not so.

Authoritative sources in New Delhi also said later that 38 members of the Assam Rifles had been forced to abandon Longju outpost in the Subansiri area and were making their way to the next outpost, Limeking, 20 miles to the South. These sources said Chinese troops were in occupation of the Longju outpost and added: “We will take all necessary steps to re-establish our frontier.”

Warning to Peking

Mr. Nehru said India had protested to China and warned her that any aggression against the Himalayan States of Bhutan or Sikkim would be aggression against India. He said the Chinese had accused Indian troops of collusion with the Tibetan rebels, but India had replied that there was no truth in this.

“Any country which has to face such a situation has to stand up to it,” Mr. Nehru said. “There is no alternative policy but to defend our borders and integrity.

Birmingham Daily Post, Saturday, 29 August 1959

New Delhi, unnerved by the sudden increase of PLA troops on its frontier, immediately deployed increased numbers of its own security forces in the border zones. Sporadic contacts between units from each side of the ill-defined border were inevitable.

After s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Timeline

- Introduction

- 1. Defence of the Realm

- 2. Himalayan Theatre

- 3. Russian Roulette

- 4. This is Our Mountain

- 5. Walong to Bomdi La

- 6. Line of Actual Control

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Plate section