- 494 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Swords and Swordsmen

About this book

"A 'must have' book for anyone who has an interest in edged weapons . . . Loades holds the reader's full attention with each sword's story that he tells." —The Lone Star Book Review

This magnificent book tells the story of the evolution of swords, how they were made, how they were used, and the people that used them. It doesn't claim to give comprehensive coverage but instead takes certain surviving examples as landmarks on a fascinating journey through the history of swords. Each is selected because it can be linked to a specific individual, thus telling their story too and giving a human interest. So the journey starts with the sword of Tutankhamun and ends with the swords of J. E. B. Stuart and George Custer. Along the way we take in Henry V, Cromwell and Uesugi Kenshin, and there is the most detailed discussion you'll find anywhere of all of George Washington's swords. The chapters on these specific swords and swordsmen are alternated with more general chapters on the changing technical developments and fashions in swords and their use.

The reader's guide on this historical tour is Mike Loades. Mike has been handling swords most of his life, as a fight arranger, stuntman and historical weapons expert for TV and stage. As much as his profound knowledge of the subject, it is his lifelong passion for swords that comes through on every page. His fascinating text is supported by a lavish wealth of images, many previously unpublished and taken specifically for this book.

"Superb . . . the most breathtaking coverage from the earliest days to modern times. Brilliant." —Books Monthly

This magnificent book tells the story of the evolution of swords, how they were made, how they were used, and the people that used them. It doesn't claim to give comprehensive coverage but instead takes certain surviving examples as landmarks on a fascinating journey through the history of swords. Each is selected because it can be linked to a specific individual, thus telling their story too and giving a human interest. So the journey starts with the sword of Tutankhamun and ends with the swords of J. E. B. Stuart and George Custer. Along the way we take in Henry V, Cromwell and Uesugi Kenshin, and there is the most detailed discussion you'll find anywhere of all of George Washington's swords. The chapters on these specific swords and swordsmen are alternated with more general chapters on the changing technical developments and fashions in swords and their use.

The reader's guide on this historical tour is Mike Loades. Mike has been handling swords most of his life, as a fight arranger, stuntman and historical weapons expert for TV and stage. As much as his profound knowledge of the subject, it is his lifelong passion for swords that comes through on every page. His fascinating text is supported by a lavish wealth of images, many previously unpublished and taken specifically for this book.

"Superb . . . the most breathtaking coverage from the earliest days to modern times. Brilliant." —Books Monthly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Swords and Swordsmen by Mike Loades in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Sword of Tutankhamun, Pharaoh of Egypt

The shade cast by your sword is upon your army and they go forth imbued with your power.

(Refrain to a rallying speech by Ramses III – twelfth century BC)

More than 3,300 years old, the sword of Tutankhamun resides today in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Looking a little neglected at the bottom of a dimly lit display case, it nonetheless retains the essence of its former splendour and remains in astonishingly good condition. The metalwork is sound and I feel sure that, if struck, it would still ring with a pure note. Dark patches mottle its surface and it no longer gleams quite as brightly but there are areas of colour, muted tones of yellow, that hint at its former, dazzling glory. Imagine it new and polished, shining brighter than the sun itself, and you will have some idea of what a fine weapon this was. Its distinctive curves are characteristic of a type of sword called a khepesh. Transliterated from the ancient Egyptian, ‘khepesh’ is a delightfully onomatopoeic word for a sword that would swish and swoosh as it sliced through the air.

Forming part of the boy king’s considerable hoard of weapons, it was among the many splendid artefacts brought to light in Howard Carter’s famous excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb in late 1922 and it was found together with a second khepesh of much smaller proportions. With an overall length of 23.2 inches the larger of the two qualifies comfortably as a sword but, at just 15.8 inches in length, the shorter one may be more accurately described as a dagger or fighting knife. There is no official length at which a dagger becomes a sword but length is certainly a deciding factor and I would say the overall length should exceed around 20 inches for a weapon to be called a true sword. However, based on shape, both these weapons may be thought of as khepeshes.

Both weapons have beautiful ebony grips, the shorter one decorated with bands of gold leaf, and both are made of bronze. Bronze, that lustrous alloy of copper, which polishes to glinting gold, can be hardened by a factor of three when worked under the hammer. You can get an edge on a bronze sword that is sharp enough to shave with. It can be cast, cut, filed and hammered into a myriad of shapes that provide both resilience and splendour. The effectiveness of a bronze sword should not be underestimated. Legions of bronze swords lie at rest in museums. They are generally in a better state of preservation than their Iron Age counterparts, though their colour has transmuted and dulled with time. In fact the soft, dusty, greyish-green appearance of so many of these weapons, caused by a coating of verdigris that forms with exposure to air, can make them appear delicate and modest, but burnish a bronze sword and you will see the fire, the toughness and a glorious, glimmering sheen that proclaims its high status and prestige. Pick one up and you will feel a weapon of weight and purpose.

Lesser khepesh of Tutankhamun, Egyptian Museum, Cairo (© Griffith Insititute, University of Oxford)

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was a soldier pharaoh – fit, strong and adept at a range of martial skills. We call him the boy king because he came to the throne, around 1336 BC, at the tender age of 9 but he did not remain a boy for long. From the age of 15, at least, he would have been in peak physical condition and capable of leading his armies into battle. It is thought that he was at least 18 or 19 years old at the time of his death in 1327 BC – time enough to have had substantial military experience. He may have died tragically young by modern standards but it was a man who died, probably from infected wounds occasioned in a chariot accident, not a boy.

The smooth-skinned features of the fabulous golden death mask can mislead us into thinking of him as a delicate and innocent youth but the wooden mannequin found in the tomb, thought to be for putting his clothes on at night, reveals a man of powerful and athletic physique. This is the Tutankhamun who is shown, in wall paintings, galloping his chariot with the reins tied around his waist and shooting his powerful angular bow. I have done this, in a replica of his chariot and with a replica of his bow. I drove the chariot across the windswept sands at Giza, with the pyramids in the background. It is among the most thrilling experiences I have ever had and it gave me an insight into Tutankhamun’s world –driving a war chariot and shooting a bow is hard, bone-shaking, physical work. Tutankhamun was far from being the milksop boy that his delicate features might suggest.

He was also a passionate hunter. There are many scenes of him hunting, both from his chariot and on foot. Two shields were discovered in his tomb and, on one of them, in bronze appliqué, is an image of the king despatching a lion with a khepesh. Allegorically it shows the pharaoh’s dominion over the natural world but it also implies a brave and fearless hunter. Hunting, at least until the mechanized wars of the twentieth century, has always been considered to be the best training for a warrior, combining the physical rigours of the chase with a need for courage and a familiarity with the letting of blood. As far as we can tell the image of Tutankhamun as a lover of rugged, adventurous and soldierly activities was more than just propaganda – it was based on the reality of his life.

His brief nine-year reign may have been of limited political significance and he would be little more than a footnote in history if it were not for the treasures of his tomb but those treasures speak of a man of great martial spirit. Among the finds was military equipment in abundance: chariots, bows, arrows, spears, shields, axes, maces, daggers, throw-sticks, fighting-sticks and, of course, the two khepeshes.

The khepesh

Archaeologists have for many years referred to the khepesh as the sickle ‘sword’. This is misleading. A lowly status is implied by suggesting that the khepesh is a derivative of the agricultural sickle. In Europe, for instance, we are used to the idea that the agricultural bill became a mainstay of medieval armies and that the threshing flail became the military flail. However, although the flail was part of pharaonic regalia, Egyptian soldiery did not go into battle with flails, sickles or any other sort of agricultural implement. Any resemblance in shape between the khepesh and the sickle is entirely superficial. On a sickle the cutting edge is on the inside of the curve, whereas on a khepesh it is on the outside. Moreover, in most examples, the shape of the curve is entirely different. That on a sickle is a steep arc, whereas on many khepeshes the curve is slight and stretched, similar in fact to the curve on the cutting edge of the epsilon axe.

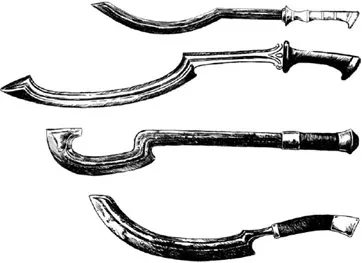

So called because its three-point attachment to the haft resembled the Greek letter E, the epsilon axe was at one stage a common weapon in the Egyptian army. Introduced into Egypt from Mesopotamia at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, epsilon axes occurred in both long and short-hafted versions. Khepeshes also evolved in Mesopotamia at around the same time, circa 2,500 BC, though it is nearly a thousand years before we have evidence of the khepesh entering Egypt. Initially only the axe migrated.

Featuring a long and narrow curving blade, the epsilon axe was not so much an axe as a sword on a stick. Unlike the many other axes in the Egyptian arsenal, wedge-shaped cleavers and hatchets, the epsilon axe cut in the same way as a sword – it sliced. Moreover it had the potential to be wielded in a very similar way to a sword. Take an epsilon axe and apply the longsword teachings of the medieval master Talhoffer to its management, for instance, and you will find that they work very well. Epsilon axes were for use with skilled and sophisticated martial art techniques. Khepesh forms owe more to the epsilon axe than they do to the sickle and the blade profile is in most cases identical.

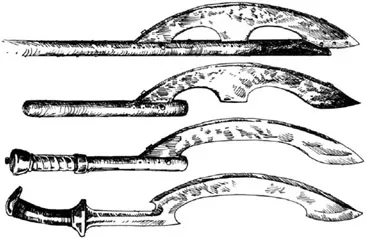

Hypothetical stages of transition from epsilon axe to khepesh

There is also an implication with the term ‘sickle sword’ that this is a weapon for the untutored recruit – the conscripted peasant straight from the land, utilizing whatever may come to hand as a makeshift weapon. Nothing could be further from the truth. I must confess to once subscribing to this prejudice but my eyes were opened the instant I held a replica khepesh in my hand. I was filming a television programme in Jordan, it was mainly about chariot archery but there was to be a small sequence discussing the difference between the khepesh and straight-bladed swords. Two Jordanian stuntmen were provided for me to use in the demonstration. As soon as I picked up the perfectly balanced replica khepesh, I realized that I had a superlative weapon in my hand and that every aspect of its design was there for a reason.

Curved swords give a more efficient cut, imparting a slicing motion as they strike the target. A curve also increases structural strength and enables a longer blade that is both rigid and robust. Because cast bronze can be somewhat brittle, it had been the challenge of the Bronze Age to be able to cast longer and longer swords – a feat that would be accomplished to an impressive degree in the late European Bronze age with straight-bladed swords – but in fourteenth-century BC Egypt it had only been possible to cast relatively short swords.

Egyptian with epsilon axe

In the case of the khepesh the overall length was maximized by having, in addition to the curved section, a sturdy straight section at the hilt end – what in later swords we might call the ‘forte’ but which is perhaps better described on the khepesh as a shank. As well as making the sword longer than it would otherwise have been, this shank provided a dedicated section of the blade for effective defence. I tried it both against an onslaught from thrusting-spears as well as from a straight-bladed sword and it was perfect at either a straight block or at setting aside the incoming blade with a deflective beat. After all, this is the section of the blade used for this purpose on any sword and the khepesh offers all the advantages of a straight blade for these functions.

Both the khepeshes from Tutankhamun’s tomb were cast with a tang – that is a continuation of the blade into the grip – making the whole a strong, single piece. With iron swords the tang became a relatively narrow, flattened rod that passed through the bored centre of a cylindrical grip. Bronze Age tangs were more often as wide as the grip itself, frequently having raised edges to create recesses for the grip plates to sit within. Many early versions of Bronze Age swords, at a time when casting technology limited the overall length of the piece, joined the grip to the blade by means of rivets. In this way the maximum length that could be cast was used entirely for the blade. Although a tanged blade is probably more robust, I think too much has been made of the likely weakness of a riveted hilt. It may be that riveted hilts did not last quite as long in heavy service but I don’t doubt that they were tough enough to deliver equally strong blows and cutting blows at that.

Nineteenth-century archaeologists decided to class bronze swords with riveted hilts as rapiers, on the supposed pretext that they were suitable only for thrusting. It is an extremely misleading practice as well as being a bogus assumption. Bronze swords with riveted hilts come in all shapes and sizes, from the slenderest of stiletto blades to the broadest of cleavers. To call any of these weapons rapiers is nonsense and also misunderstands the true definition of a rapier, which is a civilian’s sword. Fortunately these concerns are not an issue with the tanged blade versions of Tutankhamun’s specimens.

Great khepesh of Tutankhamun, Egyptian Museum, Cairo (courtesy of Robert Partridge, Ancient Egypt Magazine)

On both of Tutankhamun’s khepeshes, a polished grip of the darkest ebony contrasts beautifully with the shining blade and bears all the prestigious elegance that combinations of black and gold have always conveyed. The smaller of the two has the added embellishment of gold bands around the grip. Curling slightly around the back of the hand with a spur, the khepesh grip offers security from a sword slipping from one’s grasp when delivering a powerful cut and, swelling as it meets the blade, it gives a stop to the hand so that the sword may be used effectively with a thrust. An added refinement to the grip of the shorter khepesh is that it indents at the forward end.

From the evidence of art, most khepeshes were held with a regular power grip, whereby all the digits wrap around the hilt, with the thumb closing in the opposite direction to the fingers. This would work well for the thicker grip of Tutankhamun’s larger khepesh. However, the more slender and indented hilt of the shorter khepesh suggests a different grasp. The shape and size of the indent mirrors the shape and size of an extended thumb, indicating that this style of khepesh was held with the thumb laid lengthwise along the grip. Consider this khepesh held with the curve of the blade facing the ground and the thumb uppermost on the hilt. If you thrust forward with your hand in this position, you will notice how the tip of your thumb ends up pointing upward. Project that angle to the upward curve of the khepesh and you will be able to visualise that a thrust delivered thus would be able to enter the soft belly of a foe and yet travel upwards behind the ribs into the vital organs. Its sleek, elegant design possessed a grim functional purpose.

Tutankhamun’s larger khepesh has the point set at an angle so that when the arm is thrust forward, there is a straight line from one’s shoulder to the point of the blade. With its broad, curving blade and a point of balance that gave maximum weight behind the striking point, it was also a superlative cutting weapon. Throughout the history of the sword there has been continuous debate over the relative virtues of cutting and thrusting swords. Here at the outset of that journey is a sword that combines the key elements of both designs. It is a mystery as to why it fell so completely out of use.

As with all swords, the khepesh appears in several different forms and, conveniently, the swords from the tomb represent two of the main types. As a shorthand, I propose calling the smaller one, with its simpler form, the ‘lesser khepesh’ and the other, with its more complex shape, the ‘great khepesh’. An earlier form of khepesh, found widely in the Levant, has an especially long shank and so I call it the ‘long-shanked khepesh’. Another type has only a vestigial shank and a greater curve to the blade. I call this the crescent khepesh’. It occurs in very early representations of the weapon and, much later, as carried by the armies of Ramses III.

Great khepeshes, long-shanked khepeshes and most crescent khepeshes possess an additional feature, not seen on any other type of sword. At the junction between the shank and the curve of the blade is a hook. On the great khepesh and the long-shanked khepesh is another hook, or barb, on the back edge of the point. The primary hook, at the base of the curve, can be used to catch over the top or the side of an opponent’s shield and pull it down. You can attack with a cut, and if it is parried near the edge of the shield, you can lean in a couple more inches, pushing your blade over the shield edge, hook it, draw it back or down, then in a continuous, fluid move thrust at your opponent with the point. I found these moves both natural and intuitive and working with the khepesh opened up a whole repertoire of free-flowing combination moves that transformed my opinion of this wonderful sword.

Khepesh types (top to bottom): Lesser khepesh, Great khepesh, Long-shanked khepesh and Crescent khepesh

Tutoring the local stuntmen, who spoke no English, was at times challenging but it is surprising how much information one can convey with just half a dozen words of Arabic and a repertoire of mime. They were a jolly and charming pair and suitably tough. No complaint or fuss was offered when one suffered a bleeding lip as a result of a poor shield parry. Shields with only a central handgrip must either have the top edge supported, for instance by a shoulder, or the block must be made with the centre of the shield only. However, game though they were, there was no civilized way of testing my theory about a possible function for the barb behind the point. The Egyptians frequently fought foes, Nubians for example, who wore no or little body armour. One may imagine a great khepesh plunged into a bare stomach, and perhaps twisted as it was withdrawn, having an effective eviscerating capability. Whether or not this was so, the khepesh was certainly a weapon of ingenious design.

In spite of it having a clear martial application, there are a number of surviving khepeshes whose edges are conspicuously blunt. One such is the Sapara khepesh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index