eBook - ePub

Road to Manzikert

Byzantine and Islamic Warfare, 527–1071

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Road to Manzikert

Byzantine and Islamic Warfare, 527–1071

About this book

"

Take[s] us through 500 years of conflict from Justinian through the rise of Islam to the coming of the Turks . . . good chapters on Islamic warfare."—

Balkan Military History

In August 1071, the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV Diogenese led out a powerful army in an attempt to roll back Seljuk Turkish incursions into the Anatolian heartland of the Empire.

Outmaneuvered by the Turkish sultan, Alp Arslan, Romanus was forced to give battle with only half his troops near Manzikert. By the end of that fateful day much of the Byzantine army was dead, the rest scattered in flight and the Emperor himself a captive. As a result, the Anatolian heart was torn out of the empire and it was critically weakened, while Turkish power expanded rapidly, eventually leading to Byzantine appeals for help from Western Europe, prompting the First Crusade.

This book sets the battle in the context of the military history of the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic World (Arab and Seljuk Turkish) up to the pivotal engagement at Manzikert in 1071, with special emphasis on the origins, course and outcome of this battle.

The composition, weapons and tactics of the very different opposing armies are analyzed. The final chapter is dedicated to assessing the impact of Manzikert on the Byzantine Empire's strategic position in Anatolia and to the battle's role as a causus belli for the Crusades. Dozens of maps and battle diagrams support the clear text, making this an invaluable study of a crucial period of military history.

"A gripping story of desertion, defection and betrayal amongst the Byzantine troops and of the fleet and ferocious Seljuk steppe warriors."—Today's Zaman

In August 1071, the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV Diogenese led out a powerful army in an attempt to roll back Seljuk Turkish incursions into the Anatolian heartland of the Empire.

Outmaneuvered by the Turkish sultan, Alp Arslan, Romanus was forced to give battle with only half his troops near Manzikert. By the end of that fateful day much of the Byzantine army was dead, the rest scattered in flight and the Emperor himself a captive. As a result, the Anatolian heart was torn out of the empire and it was critically weakened, while Turkish power expanded rapidly, eventually leading to Byzantine appeals for help from Western Europe, prompting the First Crusade.

This book sets the battle in the context of the military history of the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic World (Arab and Seljuk Turkish) up to the pivotal engagement at Manzikert in 1071, with special emphasis on the origins, course and outcome of this battle.

The composition, weapons and tactics of the very different opposing armies are analyzed. The final chapter is dedicated to assessing the impact of Manzikert on the Byzantine Empire's strategic position in Anatolia and to the battle's role as a causus belli for the Crusades. Dozens of maps and battle diagrams support the clear text, making this an invaluable study of a crucial period of military history.

"A gripping story of desertion, defection and betrayal amongst the Byzantine troops and of the fleet and ferocious Seljuk steppe warriors."—Today's Zaman

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Road to Manzikert by Brian Todd Carey,Joshua B. Allfree,John Cairns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Byzantine Warfare from Justinian to Herakleios

Justinian’s Wars and the Early Byzantine Army

The high point of Byzantine power and territorial expansion took place in the sixth century during the reign of Emperor Justinian (r.527–565). Nicknamed ‘the emperor who never sleeps’, Justinian was a vigorous, intelligent and ambitious ruler who was determined to re-establish the Roman Empire throughout the Mediterranean basin, ordering Byzantine armies to fend off Sassanian Persian attacks on the eastern frontiers of Anatolia and the Levant, while also regaining parts of Italy from the Ostrogoths and North Africa from the Vandals.

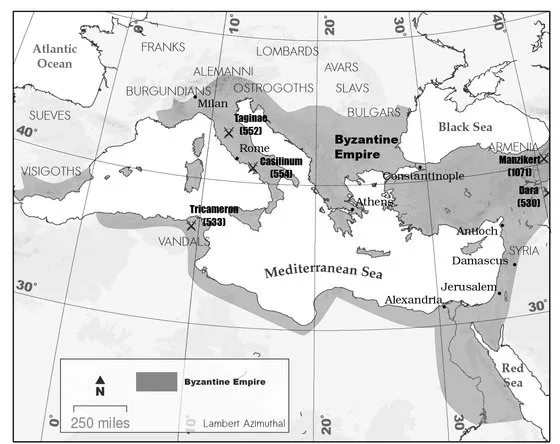

In 527, Justinian inherited an empire policed by five mobile field armies and a large number of smaller regional armies (limitanai) located along and behind the frontiers.1 These five field armies (comitatenses) were the Army of the East (a large region that included Egypt and the Levantine, Armenian, and Mesopotamian frontiers), the Army of Thrace, the Army of Illyricum, and two local imperial guard armies located in Thrace and north-western Anatolia to protect Constantinople. Each field army was commanded by a ‘Master of the Soldiers’ (magister militum).2 Justinian added two new field armies during his reign to police his new acquisitions (the Armies of Africa and Italy) and split a third off from the Army of the East to create the Army of Armenia, reflecting the increased strategic importance of this region to Byzantium, an importance that intensified from this period to the battle of Manzikert in 1071. By the end of his reign in 565 there were over twenty-five regional commands serving as both military and police forces throughout the empire.3

The constitution of Justinian’s Byzantine armies differed from those of their Roman predecessors in that cavalry, rather than infantry, was the dominant tactical arm. This switch in emphasis took place due to prolonged martial contacts with horse cultures from the Eurasian Steppes or the influence of these cultures on Near Eastern empires. The most formidable threat came from the Sassanian Persians who fought like their Parthian forerunners using predominately light cavalry archers and heavy cavalry lancers who sometimes carried bows.4 Introduced into the Roman art of war by the Emperor Hadrian (r.117–138) and widely used in the East in the last years of the Roman Empire, Roman cataphractii and clibanarii (terms often used interchangeably by classical authors) mimicked their Parthian and later Sassanian heavy cavalry foes in both equipment and tactics, functioning as heavily armoured lancers or as mounted archers.5 By the fifth century, the proportional relationship between cavalry and infantry units was 1:3 (meaning one out of three units in the Byzantine army were cavalry units, although the total number of horsemen in the army continued to be dwarfed by infantry due to the larger size of infantry units) and 15 per cent of all cavalry units consisted of heavy cavalry cataphractii, now called kataphraktoi by Byzantine authors.6 The overall percentage of cavalry in a Byzantine army continued to rise during the reign of Justinian and into the seventh century and would be a decisive tactical arm in his wars against the Sassanians. Byzantine heavy cavalry kataphraktoi supplemented standard cavalry formations, deployed to reinforce the Byzantine battle line while acting as a counterbalance to similar units deployed by the Persians.7

Byzantine military doctrine during the age of Justinian emphasized combined-arms warfare using cavalry and infantry. Much of our knowledge of Byzantine military organization and tactics comes from an anonymous Byzantine author writing sometime in the sixth century. This author, who was probably a military engineer, stated that Byzantine infantry were drawn up in square or oblong formations, with the first four ranks in the front and flanks armed with thrusting spears, while those in rear ranks were armed with javelins. Long straight swords were a common side arm. The anonymous author goes on to write that front rank infantry were equipped with large round shields one and a half yards in diameter ‘so that when they joined together they form a solid, defensive protection behind which the army can hide without anyone being injured by enemy missiles.’8 He continues, remarking that these shields ‘should have an iron circlet embossed in the centre of the shield in which a spike at least four fingers long should be fixed, both to unnerve the enemy when they see it from a distance and to inflict serious injury when used at close range.’9 Byzantine soldiers were also protected by helmets, chainmail or lamellar armour.10 Light infantry wore very little body armour and carried a composite bow with a quiver of forty arrows, a small shield and an axe for close combat, while those not equipped with bows used javelins.11

By the early sixth century, a Byzantine army’s regimental organization varied widely, made up generally of three kinds of troops: numeri, foederati and bucellarii. The numeri were regular imperial soldiers conscripted from Byzantine territory, while the foederati developed from regiments of foreign allied soldiers who settled in the Roman Empire in the late fourth century and retained their own military organization and command. By the sixth century, foederati units could be made up of soldiers from ethnically diverse regions, much like a modern foreign legion, or of a homogenous ethnic group with special tactical capabilities.12 Huns, Armenians, Persians, Arabs and Slavs served in these units, as did Germanic troops, depending on the theatre of operations.13 Each ‘Master of the Soldiers’ also had a private guard known as bucellarii, paid for out of his own purse. These units could be quite large (General Belisarios’ bucellarii guard regularly numbered over 1,000 men). By the late sixth century, these units were assimilated into the imperial army as special divisions of elite soldiers.14 In battle, Byzantine military doctrine followed a classical model, usually placing light infantry in the front to screen the army while the heavy infantry generally formed up in the centre either in front of the cavalry, or as a second line behind the cavalry, relying on the Byzantine horse to break up the enemy formation before following up. Cavalry could also be placed on the wings, usually across from enemy cavalry formations with the intention of driving off the enemy horse and attacking the vulnerable flanks of the centre infantry formations. Most Byzantine generals used their personal bucellarii guard as a tactical reserve.15

Justinian’s Empire at his death, 565.

Although trained as an officer, Justinian never took command in the field once he assumed the throne in Constantinople, instead relying on the battlefield genius of his two principal commanders, Belisarios and Narses, to expand his imperial possessions. Born in Thrace and of Greek or Thracian ancestry, Belisarios (c.505–565) joined the Byzantine army as a youth and rose quickly through the ranks of Emperor Justin I’s (r.518–527) royal bodyguard, becoming a capable and charismatic officer.16 Belisarios would cut his teeth in the eastern campaigns against Sassanian Persians, rising quickly through the ranks to become a commander. A major flashpoint on the Byzantine-Sassanian frontier was the strongly fortified border city of Dara (located near the modern village of Oguz in eastern Turkey). Dara was rebuilt into a fortress city by Justin’s predecessor, the Emperor Anastasius (r.491–518) and was the lynchpin of the Mesopotamian defences because it covered a major trading nexus south into northern Syria and north-westwards into Anatolia.17

Tug-of-war in the East and the Battle of Dara

The war between the Byzantines and the Sassanians began in 527, the last year of Justin’s reign, when the Christian king of the Caucasian kingdom of Iberia rebelled against the Sassanian Persian king Kavad (r.488–531), allegedly because the Persian king was trying to convert the region to Zoroastrianism. Worried for his life, the Iberian king then fled to Byzantine territory, where he was offered sanctuary. Kavad tried to ease tensions with Justin, even offering his own son and prince regent Chosroes (later king Chosroes I, r.531–579, sometimes Khusraw I), to the Byzantine emperor as an adoptive son. Justin refused and ordered an offensive against Persian-controlled Armenia, located just south of Iberia, led by the young commanders Sittas and Belisarios. After the death of Justin in August 527, Justinian tried to negotiate with Kavad, but to no avail. Sittas and Belisarios were defeated and Byzantine efforts in the region stalled in 529.18 In 530, Justinian appointed Belisarios ‘Master of the Soldiers’ of the Army of the East and ordered him into the region again, leading an army of 25,000 men to Dara to keep it from being taken by the Persians.19

When Belisarios arrived at Dara, he arranged his army behind a series of defensive ditches dug across the main road from Dara to nearby Nisibis just outside of the walls of the city. The ditches were probably laid out with a short central section recessed behind two longer flanking sections, connected together by two transverse sections. The defensive ditches were bridged in numerous places, allowing the Byzantine forces to cross into battle. The Byzantine centre, made up of infantry, was commanded by his chief lieutenant Hermogenes. On the far-left of the Byzantine line was stationed a detachment of Heruli cavalry, fierce Germanic horsemen originally from Scandinavia who became subjects first of the Ostrogoths and then the Huns, before becoming foederati in service of Constantinople. To their right was another larger contingent of cavalry under the Byzantine commander Bouzes, while on their right were stationed 600 Hunnic cavalry on the left of the Byzantine centre. Another 600 Hunnic cavalry drew up right of the centre, followed by a large formation of cavalry commanded by John the Armenian, a man of considerable talent whose resolve would be instrumental in many of Belisarios’ victories.20

Unwilling to negotiate with the Byzantines, King Kavad sent Firuz, his mirran (Persian Eire-An Spahbad or supreme commander), to Dara at the head of a Persian army of perhaps 40,000 men.21 The attacking Sassanian host was a combined-arms force in the tradition of great classical Mesopotamian armies of the past, complete with a reincarnation of the ‘Immortals’ (Zhayedan), an elite band of Persian soldiers who served the king as a bodyguard. Like their Byzantine counterparts, Sassanian commanders used cavalry as their primary combat arm, supported by infantry and at times, war elephants.22 Below, the fourth century Greek historian Ammianus Marcellinus, who served as a Roman staff officer under the emperors Julian the Apostate and Jovian, describes the elite Persian clibanarii of King Shapur II (r.309–379) and their support troops:

The Persians opposed us with squadrons of [clibanarii] drawn up in such serried ranks that their movements in their close-fitting coats of flexible mail dazzled our eyes, while all their horses were protected by housings of leather. They were supported by detachments of infantry who moved in compact formation carrying long, curved shields of wicker covered with raw hide. Behind them came elephants looking like moving hills. Their huge bodies threatened the destruction of all who approached, and past experience had taught us to dread them.23

Ammianus continues with a description of how well protected the clibanarii were by their armour and how some of the horsemen were lancers:

All the companies were clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff-joints conformed with those of their limbs; and the forms of human faces were so skilfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire body was covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tip of their nose they were able to get a little breath. Of these some who were armed with pikes, stood so motionless that you would have thought them held fast by clamps of bronze.24

There is evidence that by the sixth century the Sassanian art of war had transitioned away from using...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Chronology of Byzantine and Islamic History from Justinian to the First Crusade

- Introduction: Byzantium, Islam and Catholic Europe–The Battle of Manzikert as Historical Nexus

- Chapter 1 - Byzantine Warfare from Justinian to Herakleios

- Chapter 2 - Islamic Warfare from Muhammad to the Rashidun Caliphate

- Chapter 3 - Byzantine Warfare in an Age of Crisis and Recovery

- Chapter 4 - Islamic Warfare from the Umayyads to the Coming of the Seljuk Turks

- Chapter 5 - Byzantine and Seljuk Campaigns in Anatolia and the Battle of Manzikert

- Conclusion - In Manzikert’s Wake–The Seljuk Invasion of Anatolia and the Origins of the Levantine Crusades

- Notes

- Glossary of Important Personalities

- Glossary of Military Terms

- Select Bibliography

- Index