- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This historical study examines how the Bolshevik Revolution and Russian Civil War influenced events on the world stage in the Great War and beyond.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 is remembered as the catalyst for a bloody conflict between the Communist Red Army and the anti-Communist White Army. But in reality, the conflict was far more complex and multifaceted, involving forces from outside Russia.

In this probing history, Michael Foley examines the Russian Civil War in terms of its relationship to the larger conflict raging across Europe. It is an epic tale of brutal violence and political upheaval featuring a colorful cast of characters—including Tsar Nicholas II, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 is remembered as the catalyst for a bloody conflict between the Communist Red Army and the anti-Communist White Army. But in reality, the conflict was far more complex and multifaceted, involving forces from outside Russia.

In this probing history, Michael Foley examines the Russian Civil War in terms of its relationship to the larger conflict raging across Europe. It is an epic tale of brutal violence and political upheaval featuring a colorful cast of characters—including Tsar Nicholas II, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. BACKGROUND

Europe in the 18th century was to undergo a number of major upheavals that were to affect the lives of its entire people from the poorest to the richest and most powerful. One of the first major events was the French Revolution that erupted in 1789. Its effects were to resonate throughout Europe, and across the world, for decades to come. It resulted in a widespread continental and intercontinental war that involved almost all of Europe, and North America, and that was to last for almost thirty years, altering the balance of power, both domestically and internationally, forever.

The ruling classes of France were swept away and the fear of the same happening in the rest of Europe led to a series of alliances against Napoleon’s France as royal families and ruling elites came together in a series of alliances and ententes to protect their positions. It was the unification of Europe that eventually put an end to Napoleon and reinstated the monarchy in France. However, the idea of revolution did not die with the return of French royalty, as witnessed by the continent-wide outbreak of uprisings in 1848.

Russia was one of Europe’s major powers at this time. The Russian foreign minister, Rostopchin, is quoted: “Russia much by her position as to her inexhaustible resources is and must be the first power in the world.” Europe was alarmed, fearing that Russia might engulf the whole of Europe, much as France had done under Napoleon. After all, was it not the Russian Bear that had brought the greatest military strategist since Alexander the Great to his knees?

Nicholas II succeeded to the throne in 1894. He eventually replaced the Grand Duke Nicholas as commander of the forces in the First World War but was unable to lead them to victory.

Events in France, though a warning to Europe, did not actually set in motion a chain of events that were to affect the rest of the Continent. Western Europe, though writhing through the growing pains of the industrial revolution, was to take a very different path from that of Eastern Europe, and Russia. Britain led the way in development, with a swing from an agricultural economy to an industrialized power, with a corresponding leap in population growth and migration to the urban centres. The rest of Western Europe was not far behind with France, Belgium, Holland and Germany beginning to catch up as the century progressed. There were great changes in the way people worked and lived. Working hours no longer depended on daylight or the seasons. Factories had their own pattern of work and people had to be on time and stay at their work stations for as many hours as they were employed to work, often twelve or more hours a day, overseen by harsh foremen and their factory owners. However, the increase in population in the cities was not matched by development in housing and living conditions for most workers were dire, their being often worse off than they had been in the countryside. The main feature of the industrial revolution was technology: the use of iron and steel and new energy sources such as coal to power the steam engines that drove the new machines. This led to the factory system which increased the division of labour that could produce goods much faster and in greater numbers than the old system. The development of a large urban-based working class might have occurred in Western Europe but in the east in places such as Russia it didn’t. Here economies were still agrarian with industrialization sluggish.

As well as a growth of the working class in the west, there was also an expanding middle class: these two classes had similar goals in attempting to reduce the autocratic control of the old aristocracy and ruling elites. The working class were becoming more politically aware with the ideas put forward by men such as Karl Marx. By 1848 Europe was once again inflamed with revolts breaking out in all the major continental cities. Thousands died and many were exiled but the Year of the Revolutions was to have a lasting effect.

Revolts against monarchies broke out in Sicily and spread to France, Germany and Italy. Serfdom was ended in both Austria and Hungary. The Hapsburg Empire, ruled from Vienna, was riven with attempts to gain autonomy by the subject races. The absolute monarchy in Denmark ended. In France the constitutional monarchy of Louis Phillipe came to an end. Although revolution in the German states was suppressed, it did have some effect in moving the country toward a unified Germany.

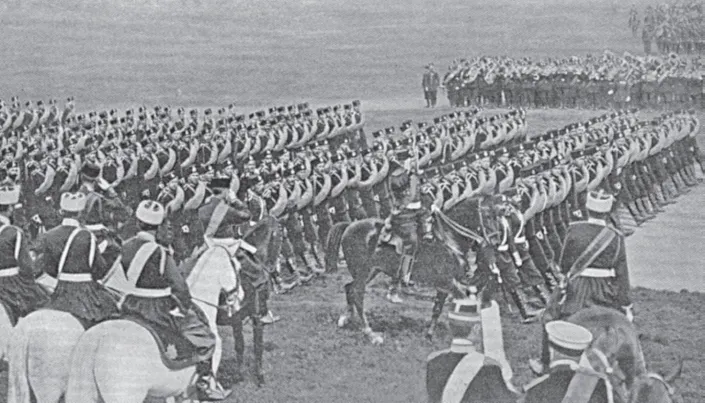

One of the Tsar’s crack regiments. Unfortunately the Russian army did not perform well in the Crimean War, the Russo-Japanese War or the First World War.

Some countries were little affected by the revolutions such as Britain where there was a small-scale Chartist movement and some trouble in Ireland. In Belgium and the Netherlands there were peaceful reforms. Some countries were not affected at all: Spain, the Scandinavian countries and most importantly Russia.

The widespread unrest that had swept across Europe had seen many heads of states swept away and although Russia was barely affected, the warning signs were there for the Tsar to see but he refused to heed them, believing that his rule was based on the power given him by God: the Divine Right of Kings. It was a sign of how the Russian monarchy was to deal with a series of threats throughout the 19th century and into the next.

However, until his death in 1881, there had been some limited reforms under Alexander II including the setting up of two institutions that seemed totally out of place in Russia: the Zemstvos which administered schools, roads and public health in the countryside and the Dumas who did the same but in the cities. They were left in place by the tsars after Alexander but were under the control of autocratic bureaucrats; the people had little influence on what decisions were made by these bodies. There were even policies put in place toward the end of the 19th century that went some way toward reversing the earlier reforms and taking back some of the control that had been given at local district level.

The situation in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century was vastly different from much of the rest of Europe where there had been some movement toward empowering the masses. Tsar Nicholas II had more power than any other person in the world at that time, with over 130 million subjects under his control. He was blind to any other political system except his own feudal autocracy. The power of the Tsar was exercised through an enormous nepotistic bureaucracy of ministers and governors, many of whom were members of the Tsar’s own family. The powers these men held were enforced by a plethora of police forces across the empire: political police, city police, rural, railway and factory police as well as the regular police force. The fact that so many police forces were seen to be needed would seem an obvious sign that there was a problem in the way the country was run.

Despite the ruthless control exercised by the Russian ruling class, there were many seen as likely to be the cause of trouble within the empire, mainly among the many groups of non-Russians that fell within the sphere of Tsarist rule such as in Finland, Poland and the Baltic States, perhaps understandable after the problems with non-Russians which had led to the assassination of Alexander II in 1881. Urban working classes were also seen as hotbeds of unrest.

Although Alexander II had been known as ‘The Liberator’ for his reforms, there was still widespread unrest because of his ruthless political policies. For example, in 1863, he brutally suppressed a rising in Poland when hundreds of Poles were executed and thousands sent to Siberia. At the same time martial law was declared in Lithuania which was to last forty years.

The Russian royal family and their bodyguard taken just before the revolution. The Tsar is in the centre with his son on his left.

Despite his reforms Alexander was assassinated in 1881 when bombs were thrown at his carriage, an armoured carriage that had been a gift from the French. The first grenade did him little harm but as he got out of the carriage another exploded, critically injuring him. He did not die immediately but later that same day. His successor, Alexander III, immediately tried to clamp down on subversive elements with the introduction of further police force.

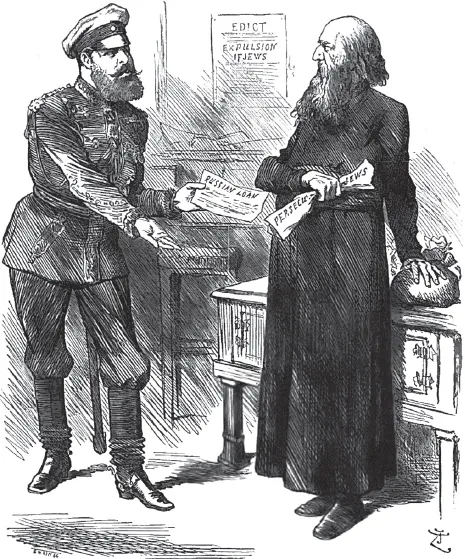

There was also another group within the empire that was problematic, the Jews, long seen as enemies of Christianity and the most likely to foment revolution. Propaganda propounded that Jews exploited the peasants, which was patently untrue but which suited the landed classes. The Jews of Russia consisted of around half the world’s Jewish population and this despite years of persecution and regular pogroms. Most of them lived in Poland, inherited by Russia in 1795 when Poland was dismembered and shared out between Austria, Prussia and Russia,

Russia itself had a large Jewish population that went back centuries. They were restricted to living in certain areas and did not enjoy the rights of other citizens. In 1827, however, they were permitted to serve in the Russian army. This still did not stop the discriminatory treatment and in 1891, for example, the majority of Jews in Moscow were expelled from the city. Government policy toward the non-Russian and the Jewish populations within the empire was assimilation which in many cases promoted the actual anti-Russian feeling they were trying to remove. This in turn led to stricter measures being enforced which simply exacerbated the matter. The Pale of Settlement was a western region of the Russian Empire that existed from 1791 to 1917. This was where Jews were allowed to live. However, they were even excluded from some urban centres within the Pale. A few more affluent or educated Jews were allowed to live outside the Pale.

However, Russia’s main problem at the time was its backwardness in terms of industrialization. More than a 100 million Russians relied on agriculture for their living. After the abolition of serfdom in 1861, much later than in the rest of Europe, peasants were afforded allotment land to farm: however, there was no land ownership by the peasants—and consequently no collateral for farming subsidies and loans—as the land was owned by the local ‘commune’, itself owned by the aristocracy or the government.

The Grand Duke Michael whom the Tsar nominated as his successor but who refused the crown.

The farm allotments were not large enough to feed a family and the peasants had to supplement their income by working for landowners. There appeared no solution to the growing number of peasants without upsetting the existing social order which was strongly resisted by the landowning classes. Reforms were therefore ineffectual. The government did go some way in trying to improve the lot of those people working in industry although numbers were still minute when compared with those on the land—around three million at the turn of the 20th century. Reforms were paltry: restrictions were placed on the hours that children could work and fines that employers could set on their workers were reduced. Strikes became the only way that urban workers could fight back and were to become the main weapon of the masses against the government

A cartoon showing Russian hypocrisy toward the Jews who were relentlessly persecuted but would be asked for loans.

Russian soldiers showing their loyalty to the Tsar by kneeling in his presence. Despite the devotion of his men, he managed to eventually turn them against him.

2. EMBRYONIC YEARS

Revolts and uprisings in Russia were not confined to the 20th century: unrest had been ongoing for centuries. The 17th century boasted a period known as the Time of Troubles when a number of revolts took place. There was also a serious famine between 1601 and 1603 when up to a third of the population died. As with revolts famine was also a common occurrence, and often the trigger for rebellion.

The Time of Troubles occurred between the death of the last Russian Tsar of the Runk Dynasty, Feodor Ivanovich, in 1598 and the establishment of the Romanov Dynasty in 1613. As well as several uprisings the Polish-Muscovite War took place between 1605 and 1616 when a significant portion of Russia was occupied by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

One of the more serious revolts of the Time of Troubles was the Bolotnikov Rebellion of 1606. Bolotnikov raised a small army consisting of escaped serfs, criminals and other unsavoury characters. Bolotnikov had a colourful background, once being a slave on a Turkish galley until freed by a passing German ship. He promised to eliminate the ruling classes of Russia and had some early success. There were a number of other small revolts going on at the same time in a similar fashion to what happened in the Russian civil war, only in 1606 the divergent groups united. The battle of Kromy in August 1606 saw the Russian army defeated. Bolotnikov’s army then besieged Moscow but his allies began to melt away when the siege was lifted. After a final victory at Kaluga, he wa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Timeline

- Introduction

- 1. Background

- 2. Embryonic Years

- 3. Suppression

- 4. War

- 5. Revolution and Civil War

- 6. The Terror Years

- 7. Denouement

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Russian Civil War by Michael Foley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.