- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Faced with the total onslaught by its enemies, in 1979, Apartheid South Africa established Vlakplaas lit. shallow farm, a 100-hectare farm nestling in the hills outside Pretoria on the Hennops River as a secret operation under the arm of C1, a counter-terrorism division of the South African Police headed by Brigadier Schoon.The first phase of Vlakplaas operations, up until 1989, was aimed at fighting the enemy: the armed wings of the liberation movements, the African National Congresss Umkhonto we Sizwe (or MK), the Pan Africanist Congresss Azanian Peoples Liberation Army (or APLA) and the South African Communist Party. The second phase was fighting organized crime in which Vlakplaas itself seamlessly adopted the mantle of organized crime in the notorious downtown area of Johannesburgs Hillbrow. The final phase, the most destructive, was as the murky Third Force that destabilized the country in an orgy of violence in the run-up to its first democratic elections, in 1994.Operating within South Africa as well as beyond the countrys borders, it will never been known how many victims can be attributed to the Vlakplaas agenda with much of the execution taking place on the farm itself but a conservative figure of 1,000 murders and assassinations has been mooted.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vlakplaas by Robin Binckes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. APARTHEID, WIND OF CHANGE AND ROOI GEVAAR

After the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, in 1913 the first Land Act allocated a total of 7.2 percent of the surface area of South Africa to 90 percent of the population. The whites received 92.8 percent. The news of this impending act led to the formation of the South African Native National Congress, the first political organization for black people in South Africa. For the first time a group of black men—Saul Msane, Josiah Gumede, John Dube, Sol Plaatjie and Pixlie Ka Isaka Seme—banded together to provide black people with a voice to protest against the passing into law of the iniquitous act.

The 7.2 percent of land allocated to black people was extended in 1923 to 13.5 percent. That year the name of the organization was changed to the African National Congress which, together with other liberation movements, finally achieved their goal of universal suffrage in 1994. In 1948 the right-wing National Party was voted into power in a country where only 10 percent of the population, the whites, was allowed to vote. The ‘Nats’ immediately began to introduce a total of 148 laws under the umbrella of apartheid (separateness). Each of these laws was designed to entrench white supremacy. Discrimination had existed in southern Africa since the 1600s with the advent of the first Europeans. Some of the laws introduced by the Dutch in the 1700s were perpetuated by the British in the 1800s and then again by the white governments in the twentieth century. After 1948 everyone in South Africa was classified by colour. White people were referred to as ‘Europeans’ (with all the privileges). Black, coloured (mixed race) and Indian people were referred to as ‘Non- Europeans’ (with very few rights). They were not allowed to own land or to vote. One of the more visible manifestations of apartheid was the Separate Amenities Act, where every aspect of life was segregated. Signs on park benches loudly proclaimed EUROPEANS ONLY; there weren’t any for non-whites as they were not allowed into parks.

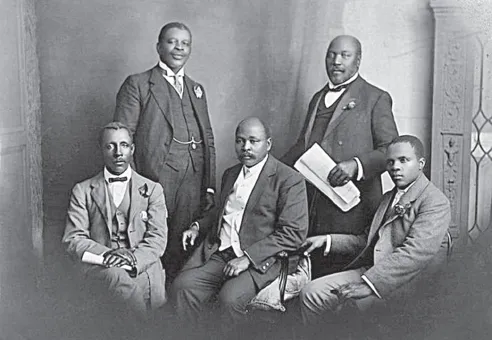

Founders of South African Native National Congress, 1912. From left: Thomas Mapike, Rev Walter Rubusana, Rev John Dube, Saul Msane and Sol Plaatjie.

This extended through to entrances to public places, counters in shops and post offices, railway carriages, buses, toilets, telephone booths and drycleaners. The Sports Act ensured that black, coloured and Indian people could not play sport against whites. Black, coloured and Indian people were not allowed to be included in any national team and blacks were not allowed into the stadiums to watch whites play sport. Further examples were the Mixed Marriages Act where whites and non-whites were not allowed to marry, the Immorality Act where sex between people of different races was illegal and punishable by five years’ imprisonment, the Bantu Education Act where black people were assured of an inferior education and the dreaded pass laws that forced every black male over the age of sixteen to carry an identification document known as a pass. Caught without it or out of the area stipulated in the pass without the written permission of the police or the local magistrate or his employer was a criminal offence. The Group Areas Act forced non-Europeans to live in areas designated for them. Only blacks with jobs were allowed to be in a ‘white’ area.

Nationalists D. F. Malan and J. B. M. Herzog, architects of apartheid and later prime ministers, seen here in 1919.

J. G. Strijdom, D. F. Malan and P. O. Sauer celebrate the National Party’s victory at the polls in 1948. (D. F. Malan Collection)

One of the major factors in the story of South Africa was the almost pathological fear of communism, the Rooi Gevaar, the red danger. On 17 July 1950, the two-year-old nationalist government of the Union of South Africa introduced the Suppression of Communism Act. At the same time the U.S. entered the McCarthy era where thousands of innocent people were accused of supporting communism, mostly without any shred of evidence. In June 1950 the Korean War broke out and UN troops, primarily American, but also including, among others, British, Australian and South African, were sent to assist South Korea in the war against the Communist North. In 1961 the world teetered on the brink of global conflagration with the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba led by the CIA, followed in 1962 by the Cuban missile crisis, followed by the Vietnam War. All these events fuelled Western paranoia.

In South Africa, the bogeyman of communism in the West was like manna from heaven for the apartheid government. Those who demanded equal rights were now labelled communist. Communism was illegal and anyone caught and prosecuted as a communist was considered by most whites to be the most evil villain imaginable. The lines between communism and democracy became extremely blurred. Because the South African government was seen by the West to be anti-communist, the iniquitous apartheid laws initially barely aroused wrist-slapping indignation, principally from the United Kingdom and the U.S.

In the 1950s Britain began to grant independence to its African colonies. In 1957 the Gold Coast became independent Ghana. In 1960 the Belgians granted independence to the Congo and Britain to Nigeria. To the apartheid South African government Africa must have appeared to be a collapsing house of cards.

On a visit to South Africa in 1960, in a speech to the South African parliament, in which he referred to the wind of change blowing across the continent, British prime minister Harold Macmillan made it clear that the time had come for independence to be granted to British colonies to the north of South Africa. He also made it clear that there were many South African policies that were unacceptable to the British government. The listening MPs met the speech with a stony silence.

Following Macmillan’s ‘wind of change’ speech, in short order nineteen African countries were granted independence by their colonial masters, Britain, France and Belgium. The wind of change had become a hurricane, sometimes with deadly effect. On 21 March 1960 South African Police opened fire on a group of protestors at Sharpeville, a township some fifty kilometres south of Johannesburg. A peaceful demonstration against the pass laws ended with sixty-nine people shot dead and 183 wounded. Mandela, on hearing the news said, “We have knocked on the door for so long. It hasn’t opened. It is time to blow it down.” The government banned both the ANC and the PAC on 8 April 1960. The ANC, which up to that time had been following Gandhi’s teachings of peaceful resistance, changed direction. The formation of the Pan Africanist Congress, a rival militant group, on 6 April 1959 under Robert Sobukwe was attracting frustrated members of the ANC and, coupled with the Sharpeville shooting, persuaded the ANC to take up arms. It formed a coalition with the Communist Party of South Africa which was predominantly white and together they launched the joint military wing known as Mkhonto WeSizwe (Spear of the Nation) or ‘MK’ with Nelson Mandela as its commander in chief. The military goal was the overthrow of the apartheid government, known as Operation Mayibuywa (to come home).

MK carried out its first military attack against the government on 16 December 1961. The 16th of December is a day revered by the Afrikaners and remembered every year with church services and a public holiday, as on that day in 1838, 464 Boers (Afrikaners) defeated a Zulu army of 20,000 at Blood River, killing between 3,000 and 10,000 Zulu warriors without losing a single man. This contributed significantly to the belief that God was on the side of the Afrikaner and thus the day became known as ‘The Day of the Vow’, subsequently changed to the ‘Day of the Covenant’. It was no accident that this date was chosen by MK to launch the armed struggle.

In 1961 MK purchased the 28-acre farm Liliesleaf on the northern outskirts of Johannesburg as a secret hideout where the communists and the ANC could meet and plan the military overthrow of the country. The money to purchase the farm was provided by Moscow. Acting on a tip-off from a CIA operative, Donald Rickart, in 1962 the police arrested Nelson Mandela near Howick in Natal. He was charged with leaving the country illegally and inciting a labour strike. He was found guilty and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment on Robben Island.

Despite Mandela’s imprisonment, the meetings plotting the overthrow of the government continued at Liliesleaf. On 11 July 1963 most of the other conspirators were arrested at Liliesleaf Farm when they were caught red-handed planning Operation Mayibuya: the police found them with plans for making forty-nine tons of ammonium nitrate, eighteen tons of black powder for manufacturing gunpowder, timing devices, landmines and hand grenades. They also found a sixty-two-page document entitled ‘How to be a Good Communist. Written by Nelson Mandela’. Mandela was brought out of prison and charged with sabotage. He became ‘Accused number one’ in the subsequent trial, known as the Rivonia Trial. He and seven others were found guilty of sabotage and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Farther afield, of what was later termed the frontline states, Kenya became the first of these countries to benefit from the wind of change, becoming independent from Great Britain in 1963. Tanganyika and Zanzibar became Tanzania in 1964, Northern Rhodesia became Zambia in the same year, followed in 1965 by the protectorate of Bechuanaland bordering South Africa becoming Botswana. Mozambique, South Africa’s immediate neighbour to the east, was already feeling the first cramps of a guerrilla campaign that would ultimately topple the Portuguese in 1974.

South Africa’s neighbour to the north, Rhodesia, had hit a stumbling block that turned out to be a wall on its path to independence. Prime Minister Ian Smith, a former RAF fighter pilot shot down in the Second World War was told by the Labour prime minister Harold Wilson that Rhodesia would only be granted independence when democratic elections—i.e. ‘one man one vote’—were held. To hasten the process, Ndabaningi Sithole and his deputy Robert Mugabe of the Zimbabwean African National Union (ZANU) joined forces with Joshua Nkomo and his Zimbabwean African People’s Union (ZAPU) to launch a war of liberation against Smith and his white government, commencing in July 1964 and continuing for fifteen years. After futile and fiery negotiations, in an attempt to hold onto minority white rule, Ian Smith and his government unilaterally declared independence (UDI) from Britain on 11 November 1965 (another date specifically and unsubtly chosen). The war began in earnest on 28 April 1966 when three groups of Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA, ZANU’s military wing) insurgents entered Rhodesia from Zambia with the aim of attacking power lines and white farmsteads. The following year MK and PAC insurgents teamed up with the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA, ZAPU’s military wing) near the Victoria Falls and clashed with Rhodesian security forces in the Zambezi valley. This was the excuse the South African government needed to get involved.

South African Police helicopters (aka SAAF helicopters) and personnel, including helicopter pilots, saw action in the Zambezi valley of Rhodesia under the guise of combating South African guerrillas.

As the war escalated and the world turned its back on Rhodesia, South Africa got sucked into the political and military quagmire by providing Ian Smith, and what had become an illegal regime, tacit and overt support. Given the excuse that her borders were under threat and conscious of the eyes of the rest of the world on Rhodesia, South Africa was well aware that she too could become the butt of sanctions that had been placed by the international community on Rhodesia. South Africa could not send in her army to assist Smith so they did the next best thing and, in 1967, members of the South African Police were sent into Rhodesia to fight shoulder to shoulder with the Rhodesian army, along with South African Air Force (SAAF) helicopters and pilots rebranded as SAP.1

After the sentencing and imprisonment of Nelson Mandela and other leaders of the resistance movement, unrest and terrorist attacks diminished. For the next decade the apartheid regime ruled with an iron fist.

In April 1975 the last American troops left Saigon, signalling an end to the Vietnam War. The following year the nationalist government of South Africa decided that black high-school children were to be taught four subjects in Afrikaans: mathematics, biology, history and physical science. After a period of stayaways and class boycotts by Soweto students, events came to a head on the morning of 16 June 1976 when nineteen-year-old Tsiietsie Mashinini led a protest march from the Morris Isaacson High School. The plan was to march to the Orlando soccer stadium where other schools would join them in a protest meeting. They never arrived at the stadium. A few hundred children left Morris Isaacson High School at 0815. By the time they had marched five and a half kilometres, there were more than ten thousand singing, chanting students. A police roadblock ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Introduction

- 1. Apartheid, Wind of Change and Rooi Gevaar

- 2. Enter BOSS

- 3. Vlakplaas and ‘Prime Evil’

- 4. Civil Cooperation Bureau

- 5. Security Police ‘Superspy’

- 6. Assassinating Two Heads of State

- 7. On the President’s Orders

- 8. Apartheid Crumbles

- 9. Fanning the Flames

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Acknowledgements