- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Up to Mametz and Beyond

About this book

Llewelyn Wyn Griffiths Up to Mametz, published in 1931, is now firmly established as one of the finest accounts of soldiering on the Western Front. It tells the story of the creation of a famous Welsh wartime battalion (The Royal Welch Fusiliers), its training, its apprenticeship in the trenches, through to its ordeal of Mametz Wood on the Somme as part of 38 Division. But there it stopped.General Jonathon Riley has discovered Wyn Griffiths unpublished diaries and letters which pick up where Up to Mametz left off through to the end of the War. With careful editing and annotation, the events of these missing years are now available alongside the original work. They tell of an officers life on the derided staff and provide fascinating glimpses of senior officers, some who attract high praise and others who the author obviously despised. The result is an enthralling complete read and a major addition to the bibliography of the period.Llewelyn Wyn Griffiths was born into a Welsh speaking family in Llandrillo yn Rhos, North Wales. He joined the Civil Service as a Tax Surveyor. Aged 24 on the outbreak of War, he was accepted for a commission in the 15th (1st London Welsh) Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers and served in the Battalion or on the staff for the rest of the War. Returning to the Inland Revenue he was responsible for the pay-As-You-Earn tax system, retiring in 1952. He filled many distinguished appointments, such as the Arts Council, and was a regular broadcaster. Awarded an Honorary DLitt by the University of Wales, he was holder of the CBE, OBE, Croix de Guerre and an MID. He died in 1977.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Up to Mametz and Beyond by Llewelyn Wyn Griffith, Jonathon Riley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Women in History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Up To Mametz

Chapter 1

Prentice Days

Cap Badge of the Royal Welch Fusiliers

The evening had declined into night without any perceptible change in quality. A heavy fall of rain had covered the streets with a thin grey film, reflecting the lights in the shop windows and silencing the tread of all who walked the pavements of Winchester in their last hours of freedom. There was so little that remained to be done, so much to say. Minutes of silence dragged their way through the dark places of the heart: speech sought a neutral path in a vague reassurance, avoiding the unreality of optimism and the sharp outline of despair. Some talk of leave and of the joy of meeting again, promises of letters, all in a coward’s effort to avoid the challenge of the morrow and to escape from the unescapable. To the very end of the last hour, and through the ritual of parting, strength and safety lay in this determination never to give shape in words to the spectre of loneliness.

Throughout the night the rain fell heavily, turning the clay into a heavy mud. We struggled down the slopes of the downs, loaded with burdens that weighed on mind and matter, and in the early hours of the morning, marched for the last time through the streets of Winchester and along the road to Southampton.

1 December 1915

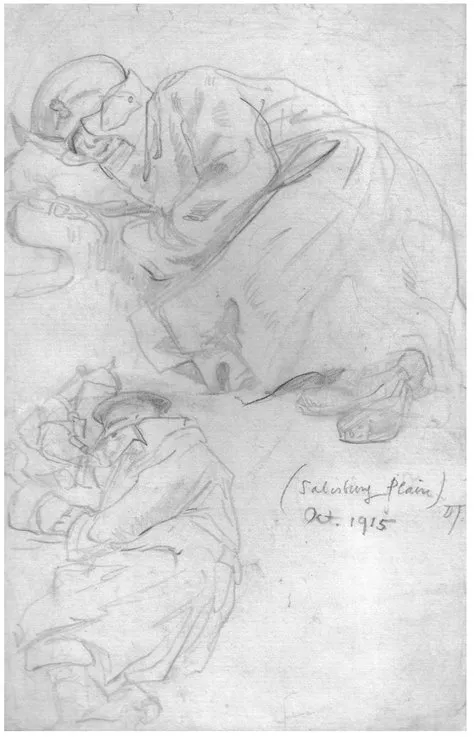

‘Salisbury Plain 1915’ by David Jones, 15 RWF. [Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum]

The day passed without change of mood, in an even drive of wind and rain, into a late afternoon that found us on a wet quayside, staring at a grey ship on a grey sea. Rain in England, rain in the Channel and rain in France; mud on the Hampshire Downs and mud in the unfinished horse-standings in Havre where we sheltered from the rain during the hours of waiting for a train. Rain beating against the trucks as we doddered through an unknown land to an unknown destination, and, late at night, as we stood in the mud of a station yard near St. Omer,1 the rain was waiting for us, to drive us along twelve miles of muddy lanes to a sodden hamlet near Aire.2

5 December 1945

Four days out of England, days and nights of fatigue and stiff-limbed weariness, nights of little sleep and days of little rest: a hundred hours of rain. Little wonder5 December 1915 that, for me, England had resolved itself into a vision of a white face looking out of a window in Winchester on a wet December morning, while France lay unrevealed behind this curtain of rain.

Next morning the world changed suddenly. We found ourselves in a flat country of pollarded willows and long poplars, red brick cottages with dark thatches, green meadows and roadside ditches, with a mild winter sun as the chief author of the change. The Army produced its unfailing remedy for all self-indulgence, its antidote against the fever of memory, in the shape of an immediate task.

At the back of our farmhouse was a stone floored outhouse with a fireplace. A careful search in the cottages of the hamlet, and in the outlying farms, disclosed eight wooden washtubs, and after some negotiation, these were borrowed and carried into the outhouse. Three men of the company were told that so long as there was a continuous supply of hot water, they would be excused all parades. In an hour’s time the enterprise was firmly established, and all day there was a steady changing of dirty men into clean men in clean clothes.

Next morning there came an urgent order from the Brigade3 that all ranks must have a bath and a change of underclothing. Worried Company Commanders4 were walking about the scattered hamlet in search of tubs, the Colonel was reputed to be cursing freely at the delay, but all in vain. ‘C’ Company had made a corner in washtubs. In the afternoon the Brigadier5 visited us, and his surprise at discovering that his orders had been forestalled by a Company officer was undisguised. Words of blame flow so easily down the slopes of rank, calling for no rehearsal, but giving shape to praise without implying excessive merit is a harder task. The stumble of phrases about the virtue of taking a personal interest in the comfort of ‘the men’ sounded somewhat unreal to a temporary officer who had but recently ceased to be a ‘man’. I record the incident in a spirit of vanity mingled with amusement, for sixteen months of soldiering had been as barren of praise as they were rich in condemnation, and the ‘bubble reputation’ had come to me from soapsuds.

The days passed in uneventful succession, and the smaller matters of life grew into vivid importance as we adjusted ourselves to the routine of a new existence. Suddenly it became the fashion to crop one’s hair. All the officers sat down in turn under the regimental barber’s clippers. We had little claim to good looks before this drastic shearing, but all the villainy latent in our faces stood out naked after a prison crop. In our simple and childish eagerness we felt that by so doing we had made ourselves better fitted for the life before us, with its unknown hardships; we saw in this act some shadow of an initiation into the great mystery of the trench world, and we were somehow proud of it. How innocent it seems at this interval of time! It was to be followed soon after by a vigorous reaction, by a desperate striving to maintain every detail of personal pride in one’s appearance. Had all the Army maintained this Spartan simplicity, the makers of brilliantine in France would not have enriched themselves so greatly at our expense.

One morning the battalion transport brought to our farmhouse a strange load from a source known vaguely as ‘Ordnance’. Bundles of sheepskin jackets, white, grey and black, were thrown down at the side of the road. We wore them under our equipment, with the fur outside. They were designed to keep us warm in the trenches, but they grew so heavy when caked with mud that they gradually sank back along the road from the front, from the infantry to the mounted men, from them to the labour battalions, until they faded away into the pit that engulfs the fashions of years gone by. They gave us the excitement of choosing the colour that pleased the most, and a slightly self conscious strutting about the hamlet: we were matriculating.

17 December 1915

Shortly afterwards we were hurled violently along our course. A solemn conference at battalion headquarters sent us back to our billets with a feeling that our quiet farmhouses were no more than a stone’s throw from the front line. Gone was that sense of comfort and security, and darkness fell quickly upon that December day. Early next morning buses would arrive to take us to the front, in itself a simple event, but bringing in its train a multitude of small domestic cares and worries about billets, equipment, rations, orders and counter orders that all but dwarfed into unreality the great transformation to be thrust upon us by the morrow. There was much to do before going to bed that night.

At eight o’clock on the morning of the 18th December, 1915, the company stood on parade in full marching order, pouches filled with ammunition, sheepskin jackets under the equipment, greatcoats rolled, and a cotton satchel containing a flannel gas-helmet slung over each man’s shoulder. Half an hour later a fleet of London buses, painted grey, shook themselves clumsily along the muddy road. We mounted them with difficulty, fattened by our gear into unwieldy bundles, projecting rifles, entrenching-tool handles and mess-tins at unexpected corners of our bodies.

The morning passed quickly. We saw for the first time ammunition dumps, field hospitals, ordnance workshops and supply parks, every village bringing to our eager and excited minds some new embodiment of war. Outside Estaires we halted, on the La Bassée road. Here was a name we knew, part of the currency of war, and the very word, painted on a wooden signboard stuck on a house, seemed to throw us into contemporary history. In the moments that followed the impact of this new discovery, war suddenly came nearer to us, and thought would have travelled far but for the persistent intrusion of the task of the hour and place, the army’s ancient cure for such indulgence. We dismounted and scattered ourselves along the roadside to eat our dinners of tinned stew – the unforgettable Maconochie.6

The day was fine, and the sky clear of clouds. An aeroplane buzzed high up above us, with little white flecks appearing from nowhere and disappearing again. This was our first seeing of war and of the intent of one man to kill another. It was difficult to translate this decorating of a blue background with white puff-balls into terms of killing. Had we ever truly believed that our military training was a perfecting of our power to kill, that we were of no value to the world unless we were skilled to hurt? I do not think so. However soldierly our muscles might be, however willingly the body accepted war, the mind was still a neutral. Through all the routine of training we were treading a path planned by others, looking to the right and to the left, sometimes looking backwards with longing, but never staring honestly into the face of the future. This is the damnable device of soldiering: confronted with an unending series of new tasks, trivial in themselves and harmless, full of the interest associated with any fresh test of skill and endurance, tempting even in their novel difficulties, the young soldier is so concerned to triumph over each passing obstacle that he does not see the goal at the end of the race. No one persuades him that drill is an exercise; that marksmanship is but a weapon; to him they are not means, but an end. If he perceived from the start that skill in the fulfilling of these daily tasks was destined only to help him to kill his fellow man, there would be fewer soldiers. The antiquity of arms is nowhere shown more clearly than in this evidence of its long practice in the art of war and its close understanding of youth.

Here, on the La Bassée road, the battalion broke up into companies, and the companies into platoons. We were to be ‘attached’ to a brigade of Guards,7 to be taught by them the art and craft of trench life, and under the shelter of their greater responsibility we were to hold the line. The four platoons of my company were apprenticed to the four companies of a battalion of Coldstream Guards, so I marched off with a subaltern at the head of his platoon, guided by a Guardsman sent to meet us. Our masters were in reserve, scattered about in some ruined farmhouses a mile to the east of the La Bassée road. Falling dusk, flashes in the sky and the noise of guns, the stammer of machine guns, shell holes in the road, and a strange emptiness over the country, as if man had deserted it, all fused together into a gloom in the mind.

Some of the men turned off to a barn, and a little later we stopped at a group of battered cottages where my subaltern and I walked into a kitchen. This was the headquarters of the Guards company. The three officers greeted us in a manner benevolently neutral, showing neither cordiality nor resentment at the sudden burden of two thrown upon the company mess. Dinner followed, and a glass of port. What had we done to our hair? Why did we wear men’s equipment and sheepskin coats? They smiled quietly, but not unkindly, at our answers, while we tried to learn as much about our task as question and answer could teach us. We were facing war, but they were turning away from it, tired in mind and body, as it seemed.

We slept upon some straw in an outhouse. I hesitated before asking whether I might take off my boots, but I was gravely assured that I might do so, as we were two miles behind the line. I was obsessed by the noise of our guns; they seemed to be firing over the cottage, shaking the floor and the walls. Through the broken corner of the roof I could see a star passing in and out through a dark cloud, and a distant rumble of transport brought a feeling that day and night were but arbitrary divisions of unending time; my period of rest was to another soldier the high noon of his activity. Thought swung uneasily from the known, with its clearly defined and pressing burden of practical worries, to the highly dramatized vision of the change that the morrow must bring into our lives. Less than twenty-four hours stood between us and the trenches; there were two kinds of men in the world – those who had been in the trenches, and the rest. We were to graduate from the one class to the other, to be reborn into the old age and experience of the front line, by the traversing of two miles over the fields in Flanders. Did one experience a sudden change of heart – would the fear of death overwhelm all else – could that fear be disguised, or must we suffer the humiliation of showing to others that for us, time was standing still? These thoughts were but clammy companions on a dark night in a strange place: reason could not drive them away, but fatigue triumphed over all in the end and brought sleep.

The day passed in inactivity: we were not to walk about more than was necessary lest we provoke a shelling of this quiet byway. In the evening we paraded on the road, carrying on our backs sufficient tackle to provide for all emergencies in a march from Flanders to the Rhine. The Guards were not so cumbered, and their greatest anxiety was to run no risk of a lack of firewood. We dared not imitate them, for our orders were stringent, and their officers would encourage no departure from the letter of our law, however unwise they deemed it in the light of their greater experience. There was little talking: we were anxious, and they were bored. The roll was called, and we set off east in separated sections – artillery formation, as it was called. Our destination was Fort Erith, a name that suggested a bastion fortified against all attack, to be held at every cost, wonderfully strong and secure, a key position, growing with every thought into an overwhelming importance as the pivot of England’s struggle against Germany. So ran the mind as we marched along a narrow road with a low hedge on one side and a long-grassed moor on the other. The moon came out, and in its light we saw that the moor was only a derelict meadow. Lights were flashing in the eastern sky, strangely high up in this flat country; that was Aubers Ridge, said my companion. We broke into single file. A singing note drooped through the air – what was that? A stray bullet. Another followed, and another, and the sound grew ominous to me. Were we not conspicuously outlined against a white road in this moonlight – could not the enemy see us? No, not at this distance: it was very rarely that anyone was hit on this road. A sudden buzz of talking ahead, and the closer shuffling of our file showed that something had caught the attention of those who marched before us, bringing that slight slackening of pace that travels down the line like a concussion in a train of shunting trucks. Three men and a stretcher lying on the roadside in the shadow ...

Table of contents

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Photographs

- Foreword by Martin Wyn Griffith

- Editor’s Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Part One - Up To Mametz

- Part Two - Beyond Mametz

- Bibliography

- Index