- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

On 19 February 1927, the city of Shanghai fell silent as a general strike gripped the factories of the industrial district. A magnet for foreign traders and businessmen (British, French, American, then later Japanese), by the 1920s the pursuit of profit had produced one of the most cosmopolitan cities that the world has ever seen. Known as the Whore of the Orient, Shanghai was a melting pot where every imaginable experience or luxury from East or West could be enjoyed. But in 1927, the citys wealth was under threat: advancing from Guangzhou in the south of China was a Guomindang army, backed by the Soviet Union and in alliance with the Chinese Communist Party, which seemed to be a clear danger to the businessmen of Shanghai.However, the armys commander, Chiang Kai-shek, a conservative, was tiring of his allies. Plotting with Shanghais most influential gangster, Chiang planned to rid himself of the Communists once and for all. The stage was set for a bloodletting in the streets of the city of Shanghai.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Shanghai Massacre by Phil Carradice in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia del XX secolo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. THE WHITE TERROR BEGINS

It is four o’clock in the morning of 12 April 1927 and the Chinese city of Shanghai is still largely asleep. In those dim but expectant moments on the rim of a new day everything pauses, everything sits still and waiting.

The last seconds of cloaking darkness cast a silence that lies thickly over people and places. It is the same in all countries, in all nations and in all parts of the world. However, here, in China, in cities like Shanghai, it is the contrast that is most obvious—the contrast between that sudden silence and the incessant murmuring of the night. It is as if the lives of the people, lives normally lived on the edge, have suddenly come to a halt.

On the riverfront the sampans, ferries and skiffs lie solidly and silently against their wharfs. The Yangtze Delta still pushes wavelets against the vessels and the jetties but somehow they make no noise. The boats that normally rock in the swell now sit defiantly still in the water. The usual slap of wood on wall, a sound found in any port or boatyard on the river, seems to have disappeared even though the boats are open to the elements and the tide.

Shanghai, bustling port and commercial centre.

A Kuomintang parade in Gannan.

Below the decks of the larger vessels the crews are draped, motionless across the decks. Even their snores are muted and the normally incessant patter of rodents’ feet across the scuppers and in the bilges is finally still and silent.

Across the port and out into the sprawling city streets tired rickshaw drivers lie curled like giant ammonites in the backs of their vehicles. The lucky ones, the richer ones who can afford such luxuries, are covered by blankets that have, all day, doubled as padding for the customer’s seats.

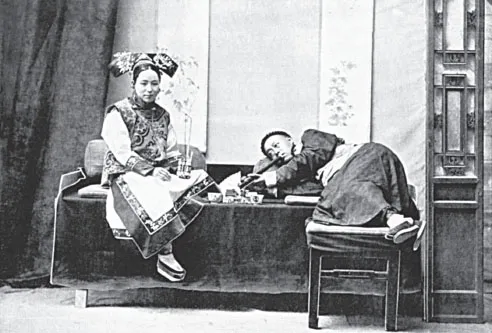

In the opium dens nothing moves. The lights are out and late smokers, drugged into heavenly oblivion, lie comatose and unthinking. Only the sickly sweet smell of the dope betrays the function of the shops. Dogs and cats that have prowled restlessly throughout the nighttime hours have now, at last, taken to their beds, their places of sanctuary where they will rest and fall instantly asleep; children turn on their futons and dream of pirate junks and sampans that will one day carry them across the bounding East China Sea; men and women snore and slumber on, dreaming of wealth that will probably never come. For a few brief moments there is peace in the city.

And then a sudden bugle call splits the predawn air, cutting like a razor through the darkness. It is strident, startling the birds that are still roosting in the spidering bushes of Shanghai’s parks. It shakes the stunted branches of the camphor trees along the city’s streets and alleyways. The bugle call alarms the birds, causing them to rise like giant mosquito clouds into the air. They squawk and cry and whirl away to safer, less noisy locations.

Opium-smoking, 1906. (Sanshichiro Yamamoto)

With the last notes of the bugle finally echoing into nothingness, the dogs that have so recently settled to sleep begin to shift once more. Slowly, stretching their lean bodies into wakefulness, they begin to turn and rise to their feet. These last bugle notes are on that deep-rooted wavelength that only dogs can ever know and soon, fur rising like icicles along their spines, the howl of the wakened animals is echoing from the back streets and gardens. In unison they bounce off the thin wooden walls of the city’s shacks and houses.

The noise of the blaring bugle and the shrieking of the wakened animals disturb people in many different parts of the city. From the International Settlement and the French Concession to the dwellings of the rich Chinese merchants and bankers they set off a thin but compelling frisson of fear. Principally, however, it is in the poorer quarters where the workers live and try their best to survive, that the bugle call is noted most.

For those who have an acute or more than normal awareness of the tensions that have recently fallen across the city it is a call to arms. These few individuals have some understanding of the lurking dangers of the time, an understanding of the potential for disaster that this bugle call holds. It is a warning to be heeded—and heeded quickly.

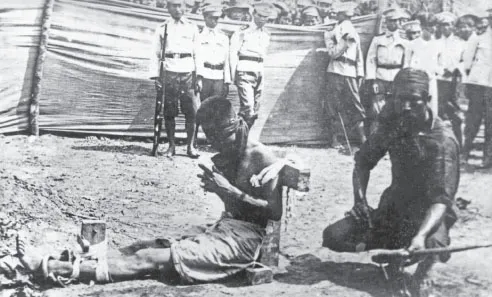

An execution takes place in the street.

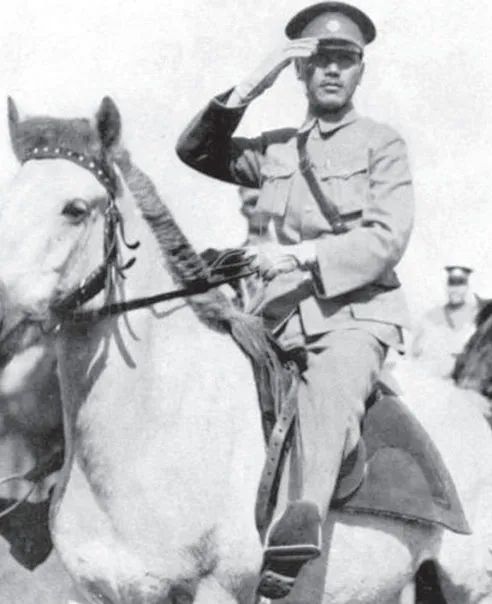

With a sudden lurch of their bellies the more astute listeners are instantly awake, tracing the bugle call to the headquarters of General Chiang Kai-shek, commander of the National Revolutionary Army and the most powerful man in the region. Most of them have never seen Chiang; some have caught a brief glimpse as he drives past in his car. They all know of him, however, and Chiang gives every single one of them a good reason to be afraid.

For others, less aware or perhaps wrapped more deeply in the cocoon of sleep, the noise is no more than a distant growling at the corner of their dreams. For them the last few moments of innocence will continue to be blissful.

The choice is simple: turn over and go back to sleep or dress quickly and flee. Hundreds choose the former option. It is a fateful decision, in some cases a fatal one. It is a decision that condemns far too many of the half-wake workers to an unforgiving end. Within minutes of the warning bugle, bands of thugs, operating under the auspices of the China Mutual Advancement Society, descend on the houses of the sleeping victims. They are looking for union men, for Communists and for any left-wing supporters they can find. They are looking, in fact, for opponents of General Chiang Kai-shek.

Whirling through the streets like the typhoons and whirlwinds that the area knows only too well, the thugs smash open the flimsy doors or crash through windows that are locked but provide little security. Some of the more evil-natured simply stand waiting, menacing and perhaps more terrifying for that, in the darkness. In a drumming tattoo of anger and fury some of them slam their swords and staves against the ground or fence posts demanding that the men inside the houses come out to meet their fate.

General Chiang Kai-shek in martial pose.

Most of the attackers from this first wave of assaults are members of the criminal triads that proliferate in Shanghai. In particular they come from the Green Gang, one of the most vicious and effective of all the city’s underworld groups. They are deeply embroiled in crime: it is commonly said that there is almost no criminal activity in the city that does not admit to the hands of the Green Gang somewhere in the mess.

Big-Eared Du, gangster leader.

Chiang has patronized the Green Gang and cleverly enrolled them on his side. He has bribed their leader Du Yue-sheng and other headmen, people like the policeman-cum-robber-cum-jewel thief Huang Jinrong, with promises of money and power. He has judged them well, these bastions of criminal society; the bandit leaders fall in happily at his side.

For the ordinary members of the gangs the prospect of violence is more than enough. For them the wielding of power starts and ends with the brutality of the riot and the mêlée. The taking of life—or the losing of it—warrants little more than a wry, inscrutable smile or shrug. At the most basic level, they like violence. Nevertheless, the gang members have a pragmatic view of life. None of the Green Gang will, today, pass up on the chance of robbery or looting from the houses of their victims, particularly if they gain access to any of the foreign legations.

For their task this morning Green Gang members have dressed in the traditional blue dungarees worn by workers all over the country. They also sport white armbands—that bear the words ‘Kung’ or Workers—startlingly bright against the blue denim of the dungarees. All are armed, usually with knives and clubs, but some carry swords and pistols.

For those union men and Communists who are caught in their houses or as they emerge yawning and disorientated from their doorways, there are beatings and, even at this early stage, many are killed before they know what is happening. Those who manage to escape the initial onslaught are pursued in a terrifying frenzy as they flee or try to make a stand.

As dawn breaks above Shanghai dozens of the victims are corralled into groups and then executed on the city streets. Beheading is the preferred method of execution although at this early stage of the massacre many are shot or simply clubbed to death.

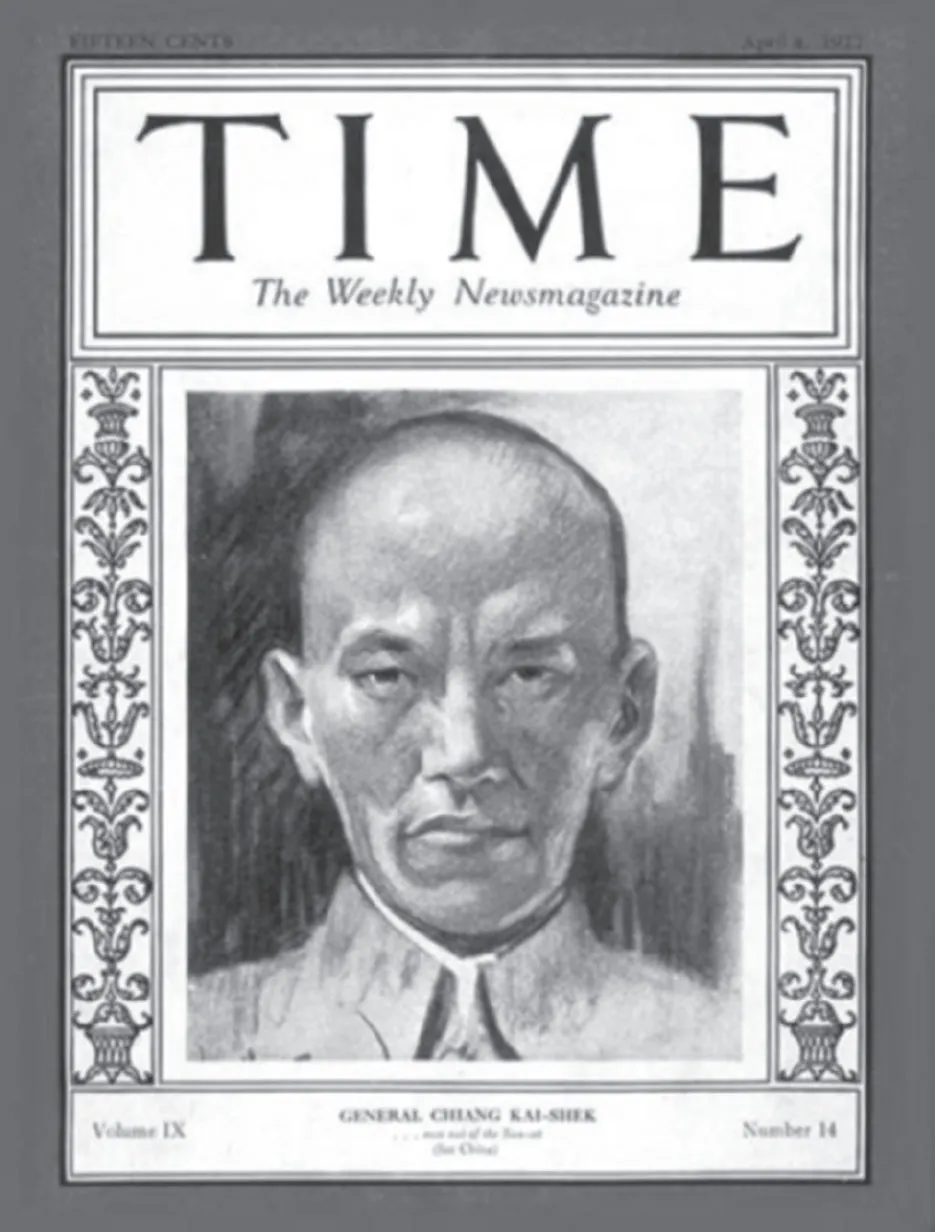

Chiang Kai-shek on the cover of Time magazine’s April 1927 edition.

In that strange, disconcerting acceptance that seems to signify the Chinese character, once they are lined up and made to kneel before their executioners, many of the Communists bow their heads to the executioners. Bowing to the inevitable as scholars would have it. But that would be too simple a description, too simple by far—and yet still they kneel there in the streets and wait. It is, perhaps, an acceptance that this is their fate, that this is how it has always been intended to finish.

District offices of the trade unions are also targeted. Here members of the Green Gang have little chance of dishing out beatings, arrests and executions, at least not at this time of the morning. Party officials and staff will not be here until eight or nine o’clock but there is still the prospect of looting and the thought of wanton destruction is always a welcome possibility. The triads go happily about their work. In some instances the Communists try to fight back but such opposition is rare. They are outnumbered and, as far as violence is concerned, totally outclassed by the gangs.

Inevitably, looting—mostly but not totally the preserve of the Green Gang— continues for some time. Accusations made later that Chiang’s men have confiscated money and possessions from their victims are met with blank denials. So too is the belief that ‘donations’ have been extorted from wealthy Shanghai businessmen. Maybe, maybe not, but either way it is hard to believe that the executioners are altruistic enough not to have helped themselves to a little something on the side.

It is not long before Chiang sends in his soldiers to assist the triad gangs. Death and destruction need to be more organized, more controlled, he feels. The gangs have done their work—the initial assault was both brutal and terrifying—but now it needs more than a simple blunt-headed machine like the triads. Now it needs a more formal approach to death.

More arrests and more beheadings quickly follow in the wake of the soldiers as blood, quite literally, flows down the city streets. Not for nothing does Time magazine later bestow the epithet of ‘Hewer of Communist Heads’ on Chiang’s accomplice and supporter General Bai Chongxi. Bai is the man with direct responsibility for the massacre and for the killings that will follow over the next few weeks. The White Terror has now truly begun.

Shanghai, the Old City, as seen today, little changed in ninety years. (w:User:PHG)

It is not all mute acceptance and bowing to the inevitable from the Communists and trade unionists, however. In Nantao and Chapei, two industrial sections of Shanghai, there is heavy fighting as workers’ pickets, militia units formed in readiness for just such an event as this, put up stern resistance. The battles last until ten in the morning when the final pickets are either shot or disarmed by soldiers of the NRA and by units of the China Mutual Advancement Society. According to Chiang’s compatriot and fellow army commander Pai Ch’ung-hsi over 300 Communists are arrested and more than two thousand rifles seized.

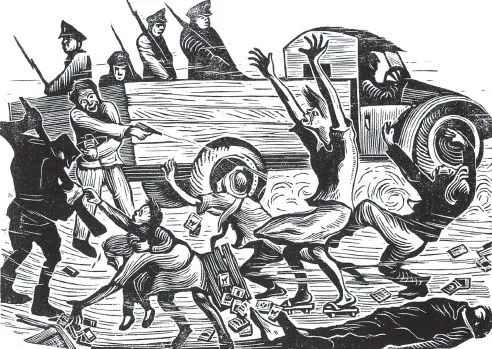

A contemporary cartoon showing the massacre taking place.

The intervention of the soldiers destroys, for once and for all, any illusion that Chiang Kai-shek is neutral or not involved in the killings. It is not a matter that concerns the hunted Communists: they are simply trying to survive. But for the foreigners in the legations it is an important message and consideration.

While death was left in the hands of the Green Gang there was always the option of shielding behind anonymity but not now. These are Chiang’s soldiers on the streets and they are operating on his orders. Not that he has ever wanted to hide the fact. It is just that now the director and the direction of the assaults are clear to everyone, Chinese and foreign ‘ba...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1. The White Terror Begins

- 2. Looking Back

- 3. Sun Yat-sen

- 4. The Northern Expedition

- 5. What to do and Why to do it

- 6. After Effects

- 7. Finishing Touches

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix: Contemporary Liangyou Covers

- Acknowledgements