- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

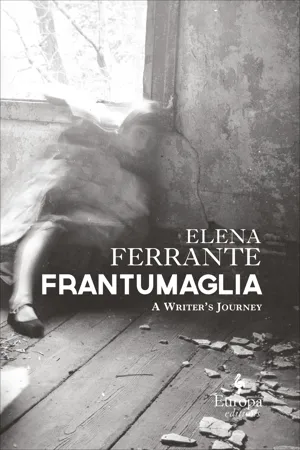

One of

The Guardian's Best Books of the Year: Personal writings by the anonymous author who became a literary phenomenon with

My Brilliant Friend.

The writer known as Elena Ferrante has taken pains to hide her identity in the hope that readers would focus on her body of work. But in this volume, she invites us into Elena Ferrante's workshop and offers a glimpse into the drawers of her writing desk—those drawers from which emerged her three early standalone novels and the four installments of the Neapolitan Novels, the New York Times–bestselling "enduring masterpiece" ( The Atlantic).

Consisting of over twenty years of letters, essays, reflections, and interviews, it is a unique depiction of an author who embodies a consummate passion for writing. In these pages, Ferrante answers many of her readers' questions. She addresses her choice to stand aside and let her books live autonomous lives. She discusses her thoughts and concerns as her novels are being adapted into films. She talks about the challenge of finding concise answers to interview questions. She explains the joys and the struggles of writing, the anguish of composing a story only to discover that that story isn't good enough. She contemplates her relationship with psychoanalysis, with the cities she has lived in, with motherhood, with feminism, and with her childhood as a storehouse for memories, impressions, and fantasies. The result is a vibrant and intimate self-portrait of a writer at work.

"Everyone should read anything with Ferrante's name on it." — The Boston Globe

The writer known as Elena Ferrante has taken pains to hide her identity in the hope that readers would focus on her body of work. But in this volume, she invites us into Elena Ferrante's workshop and offers a glimpse into the drawers of her writing desk—those drawers from which emerged her three early standalone novels and the four installments of the Neapolitan Novels, the New York Times–bestselling "enduring masterpiece" ( The Atlantic).

Consisting of over twenty years of letters, essays, reflections, and interviews, it is a unique depiction of an author who embodies a consummate passion for writing. In these pages, Ferrante answers many of her readers' questions. She addresses her choice to stand aside and let her books live autonomous lives. She discusses her thoughts and concerns as her novels are being adapted into films. She talks about the challenge of finding concise answers to interview questions. She explains the joys and the struggles of writing, the anguish of composing a story only to discover that that story isn't good enough. She contemplates her relationship with psychoanalysis, with the cities she has lived in, with motherhood, with feminism, and with her childhood as a storehouse for memories, impressions, and fantasies. The result is a vibrant and intimate self-portrait of a writer at work.

"Everyone should read anything with Ferrante's name on it." — The Boston Globe

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Frantumaglia by Elena Ferrante, Ann Goldstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

LETTERS: 2011-2016

A COMPANION BOOK

Dear Sandra,

Maybe we ought to tell readers why we’ve decided to collect some of these interviews. It’s something I’ve felt we should do since September 23, 2015, when your cryptic email arrived, with a file of interviews attached and, as the only text, the subject line, which said: “Interviews. Will you let me know if you can open them and understand anything?” When did it begin to seem to you and Elena that it made sense to collect them?

Maybe we ought to tell readers why we’ve decided to collect some of these interviews. It’s something I’ve felt we should do since September 23, 2015, when your cryptic email arrived, with a file of interviews attached and, as the only text, the subject line, which said: “Interviews. Will you let me know if you can open them and understand anything?” When did it begin to seem to you and Elena that it made sense to collect them?

In the interviews Elena speaks of the importance that the point of view of others, the written dialogue with journalists from so many countries, has had in nurturing her own reflections on writing, and that much is clear to me. But when did you two look each other in the eye and think: it would be nice to collect them, so that readers, too, can find them all in one place? You didn’t at first have the idea of a whole section, right, and wanted to publish just a few? Or maybe you didn’t look each other in the eye?

Ciao, Simona

Dear Simona,

I’m going to answer—Elena wanted to but says she would drag it out and bore you.

So, as to your little question, we didn’t look each other in the eye because we were on the telephone. I told the author that we were going to reprint Frantumaglia in Italy and suggested that it might be a good idea to publish the text in English as well, because in English we had brought out only a few excerpts, and they had appeared only in digital form.

As you know, I am extremely fond of this book, which to me reads almost like a story, with its variety of themes and characters. So I thought it could be enhanced with a collection of the interviews that Elena has done since the publication of the four installments of My Brilliant Friend, or the Neapolitan Quartet, as it’s called in English.

The little problem was that, having promised the first publishers to whom we sold the rights that Elena would do an interview for each of those countries, the author suddenly found herself having to respond to some forty interviews, from all over the world. Certainly too many for an appendix. We thought it would be helpful to bring you into the discussion as we tried to figure out what to do and how to organize the section.

Anyway, looking through the interviews we realized that the material is consistent with the structure of Frantumaglia, which over all contains the now twenty-five-year history of an attempt to show that the function of an author is all in the writing: “It originates in it, is invented in it, and ends in it,” as Elena says. And I think that readers would be interested in the growing number of questions in recent years about the literary and cultural tradition that the novels draw on, about the role of female thought in the construction of figures like Lena and Lila, about the reasons that the two girls have broken through into contexts and cultures far from Naples and from Italy.

Michael’s observations also seemed important to the author, helping to clarify the point of this last part of the book. Michael says that with this section we’ll give readers a sort of internal history of Elena’s motivations, of the struggle to give them shape, and of how they changed over time. Which is true. In her answers one feels the effort involved in finding the words, in explaining herself; I like this, and I know she does, too. After all, the Frantumaglia project has always been to give her readers, from Troubling Love up to now, work that, without too many veils, and by making use of various fragments, notes, explanations, even contradictions, accompanies the works of fiction like a companion book.

Ciao, Sandra

NOTE

In this e-mail exchange, the editors referred to are Simona Olivito, of Edizioni E/O, and Michael Reynolds, of Europa Editions.

1.

THE BRILLIANT SUBORDINATE

Answers to questions from Paolo di Stefano

Di Stefano: Elena Ferrante, how did you make the transition from one type of psychological-family novel (Troubling Love and The Days of Abandonment) to a novel that, like this, promises to be the first of a trilogy or a tetralogy, and which is in plot and in style so centrifugal and, at the same time, so centripetal?

Ferrante: I don’t feel that this novel is so different from the preceding ones. Many years ago I had the idea of telling the story of an old person who intends to disappear—which doesn’t mean die—without leaving any trace of her existence. I was fascinated by the idea of a story that demonstrated how difficult it is to erase yourself, literally, from the face of the earth. Then the story became complicated. I introduced a childhood friend who served as an inflexible witness of every event, small or large, in the life of the other. Finally, I realized that what interested me was to dig into two female lives that had many affinities and yet were divergent. That’s what I did. Of course, it’s a complex project, as the story covers some sixty years. But Lila and Elena are made of the same material that fed the other novels.

Di Stefano: The two friends whose childhood story is told, Elena Greco, the first-person narrator, and her friend-enemy Lila Cerullo, are similar yet different. They continuously overlap just when they seem to be growing apart. Is it a novel about friendship and how an encounter can determine a life? But also about how attraction to the bad example helps develop an identity?

Ferrante: Generally, someone who asserts his personality, in doing so, makes the other opaque. The stronger, richer personality obscures the weaker, in life and perhaps even more in novels. But, in the relationship between Elena and Lila, Elena, the subordinate, gets from her subordination a sort of brilliance that disorients, that dazzles Lila. It’s a movement that’s hard to describe, but for that reason it interested me. Let me put it like this: the many events in the lives of Lila and Elena will show how one draws strength from the other. But beware: not only in the sense that they help each other but also in the sense that they ransack each other, stealing feeling and intelligence, depriving each other of energy.

Di Stefano: How did memory and the passage of time, distance (temporal and perhaps spatial), influence the development of the book?

Ferrante: I think that “putting distance” between experience and story is something of a cliché. The problem, for the writer, is often the opposite: to bridge the distance, to feel physically the impact of the material to be narrated, to approach the past of people we’ve loved, lives as we’ve observed them, as they’ve been told to us. A story, to take shape, needs to pass through many filters. Often we begin to write too soon and the pages are cold. Only when we feel the story in each of its moments, in every nook and cranny (and sometimes it takes years), can it be written well.

Di Stefano: My Brilliant Friend is also a novel about violence in the family and in society. Does the novel describe how a person manages (or managed) to grow up in violence and/or in spite of violence?

Ferrante: In general, one grows up warding off blows, returning them, even agreeing to receive them with stoic generosity. In the case of My Brilliant Friend, the world in which the girls grow up has some obviously violent features and others that are covertly violent. It’s the latter that interest me most, even though there are plenty of the first.

Di Stefano: On page 130 there’s a wonderful sentence, about Lila: “She took the facts and in a natural way charged them with tension; she intensified reality as she reduced it to words.” And then on page 227: “The voice set in the writing overwhelmed me . . . It was completely cleansed of the dross of speech.” Is that a statement of style?

Ferrante: Let’s say that, among the many methods we employ to give a narrative order to the world, I prefer one in which the writing is clear and honest, and in which when you read about the events—the events of everyday life—they are extraordinarily compelling.

Di Stefano: There is a more sociological thread: Italy in the years of the boom, the dream of prosperity that reckons with ancient hostilities.

Ferrante: Yes, and that thread runs through to the present. But I reduced the historical background to a minimum. I prefer everything to be inscribed in the actions of the characters, both external and internal. Lila, for example, already at the age of seven or eight, wants to become rich, and drags Elena along, convinces her that wealth is an urgent goal. How this intention works inside the two friends; how it’s modified, how it guides or confuses them, interests me more than standard sociology.

Di Stefano: You seldom yield to dialectal color: you use a few words, but usually you prefer the formula “he/she said in dialect.” Were you never tempted by a more expressionistic coloring?

Ferrante: As a child, as an adolescent, the dialect of my city frightened me. I prefer to let it echo for a moment in the Italian, as if threatening it.

Di Stefano: Are the next installments finished?

Ferrante: Yes, in a very provisional state.

Di Stefano: An obvious but necessary question: how autobiographical is the story of Elena? And how much of your literary passions are in Elena’s readings?

Ferrante: If by autobiography you mean drawing on one’s own experience to feed an invented story, almost entirely. If instead you’re asking whether I’m telling my own personal story, not at all. As for the books, yes, I always cite texts I love, characters who molded me. For example, Dido, the Queen of Carthage, was a crucial female figure of my adolescence.

Di Stefano: Is the game of alliteration “Elena Ferrante—Elsa Morante” (a passion of yours) suggestive? Is any relationship of Ferrante to Ferri (your publishers) only imaginary?

Ferrante: Yes, absolutely.

Di Stefano: Have you never regretted choosing anonymity? Reviews tend to linger more on the mystery of Ferrante than on the qualities of the books. In other words, have the results been the opposite of what you were hoping for, in emphasizing your hypothetical personality?

Ferrante: No, I have no regrets. As I see it, extracting the personality of the writer from the story he offers, from the characters he puts onstage, from the landscapes, from the objects, from interviews like this—in short, from the tonality of his writing entirely—is simply a good way of reading. What you call emphasizing, if it’s based on the works, on the energy of the words, is an honest emphasis. What’s very different is the media’s emphasis, the predominance of the author’s image over his work. In that...

Table of contents

- PRAISE

- ALSO BY ELENA FERRANTE

- CONTENTS

- I. PAPERS: 1991-2003

- II. TESSERAE: 2003-2007

- III. LETTERS: 2011-2016

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- NOTES