eBook - ePub

The Screens

About this book

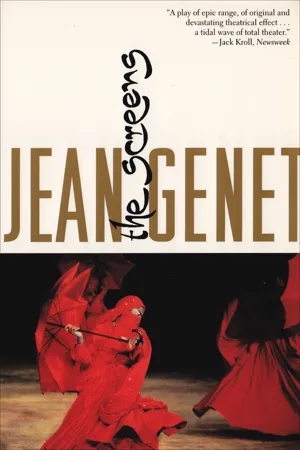

From the acclaimed author of

The Balcony: "A play of epic range, of original and devastating theatrical effect…a tidal wave of total theater" (Jack Kroll,

Newsweek).

Jean Genet was one of the world's greatest contemporary dramatists, and his last play, The Screens, is his crowning achievement. It strikes a powerful, closing chord to the formidable theatrical work that began with Deathwatch and continued, with even bolder variations, in The Maids, The Balcony, and The Blacks.

A philosophical satire of colonization, military power, and morality itself, The Screens is an epic tale of despicable outcasts whose very hatefulness becomes a galvanizing force of rebellion during the Algerian War. The play's cast of over fifty characters moves through seventeen scenes, the world of the living breaching the world of the dead by means of shifting the screens—the only scenery—in a brilliant tour de force of spectacle and drama.

Jean Genet was one of the world's greatest contemporary dramatists, and his last play, The Screens, is his crowning achievement. It strikes a powerful, closing chord to the formidable theatrical work that began with Deathwatch and continued, with even bolder variations, in The Maids, The Balcony, and The Blacks.

A philosophical satire of colonization, military power, and morality itself, The Screens is an epic tale of despicable outcasts whose very hatefulness becomes a galvanizing force of rebellion during the Algerian War. The play's cast of over fifty characters moves through seventeen scenes, the world of the living breaching the world of the dead by means of shifting the screens—the only scenery—in a brilliant tour de force of spectacle and drama.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SCENE ONE

Four-paneled screen. Painted on the screen: a palm tree, an Arab grave.

At the foot of the screen, a rock pile. Left, a milestone on which is written: AÏN/SOFAR, 2 Miles.

Blue light, very harsh.

SAïD’S costume: green trousers, red jacket, tan shoes, white shirt, mauve tie, pink cap.

THE MOTHER’S costume: violet satin dress, patched all over in different shades of violet. Big yellow veil. She is barefooted. Each of her toes is painted a different—and violent—color.

SAïD (twenty years old), tie askew. His jacket is completely buttoned. He enters from behind the screen. As soon as he is visible to the audience, he stops, as if exhausted. He turns toward the wing from which he entered and cries out.

SAïD: Rose! (A pause.) I said rose! The sky’s already pink as a rose. The sun’ll be up in half an hour. . . . (He waits, rests on one foot, and wipes his face.) Don’t you want me to help you? (Silence.) Why? No one can see us. (He wipes his shoes with his handkerchief. He straightens up.) Watch out! (He is about to rush forward, but remains stock-still, watchful.) No, no, it was a grass snake. (He speaks less loudly as the invisible person seems to draw closer. His tone finally becomes normal.) I told you to put your shoes on.

Enter an old Arab woman, all wrinkled. Violet dress, yellow veil. Barefooted. On her head, a cardboard valise. She too has emerged from behind the screen, but from the other side. She is holding her shoes—a red button-boot and a white pump.

THE MOTHER: I want them to be clean when I get there.

SAïD (crossly): You think they’ll have clean shoes? And new shoes besides? And even clean feet?

THE MOTHER (now coming up to SAïD): What do you expect? That they have new feet?

SAïD: Don’t joke. Today I want to stay sad. I’d hurt myself on purpose to be sad. There’s a rock pile. Go take a rest.

He takes the valise, which she is carrying on her head, and puts it down at the foot of the palm tree. THE MOTHER sits down.

THE MOTHER (smiling): Sit down.

SAïD: No. The stones are too soft for my ass. I want everything to make me feel blue.

THE MOTHER (still smiling): You want to stay sad? I find your situation comical. You, my only son, are marrying the ugliest woman in the next town and all the towns around, and your mother has to walk six miles to go celebrate your marriage. (She kicks the valise.) And to bring the family a valise full of presents. (Laughing, she kicks again and the valise falls.)

SAïD (sadly): You’ll break everything if you keep it up.

THE MOTHER (laughing): So what? Wouldn’t you get a kick out of opening, in front of her eyes, a valise full of bits of porcelain, crystal, lace, bits of mirror, salami. . . . Anger may make her beautiful.

SAïD: Her resentment will make her funnier looking.

THE MOTHER (still laughing): If you laugh until you cry, your tears’ll bring her face into focus. But the point is, you wouldn’t have the courage . . .

SAïD: To . . .

THE MOTHER (still laughing): To treat her as an ugly woman. You’re going to her reluctantly. Vomit on her.

SAïD (gravely): Should I really? What’s she done to marry me? Nothing.

THE MOTHER: AS much as you have. She’s left over because she’s ugly. And you, because you’re poor. She needs a husband, you a wife. She and you take what’s left, you take each other. (She laughs. She looks at the sky.) Yes, sir, it’ll be hot. God’s bringing us a day of light.

SAïD (after a silence): Don’t you want me to carry the valise? No one would see you. I’ll give it back to you when we get to town.

THE MOTHER: God and you would see me. With a valise on your head you’d be less of a man.

SAïD (very surprised): Does a valise on your head make you more of a woman?

THE MOTHER: God and you . . .

SAïD: God? With a valise on my head? I’ll carry it in my hand. (She says nothing. After a silence, pointing to the valise): What did you pay for the piece of yellow velvet?

THE MOTHER: I didn’t pay for it. I did laundry at the home of the Jewess.

SAïD (counting in his head): Laundry? What do you get for each job?

THE MOTHER: She doesn’t usually pay me. She lends me her donkey every Friday. And what did the clock cost you? It doesn’t run, true enough, but it’s a clock. . . .

SAïD: It’s not paid for yet. . . . I still have sixty feet of wall to mason. Djellul’s barn. I’ll do it the day after tomorrow. What about the coffee grinder?

THE MOTHER: And the eau de Cologne?

SAïD: Didn’t cost much. But I had to go to Aïn Targ to get it. Eight miles there, eight miles back.

THE MOTHER (smiling): Perfumes for your princess! (Suddenly, she listens.) What’s that?

SAïD (looking into the distance, left): Monsieur Leroy and his wife on the national highway.

THE MOTHER: If we’d stopped at the crossing, they might have given us a lift.

SAïD: US?

THE MOTHER: Normally they wouldn’t have, but you’d have explained that it’s your wedding day . . . that you’re in a hurry to see the bride . . . and I’d have so enjoyed seeing myself arrive in a car.

A silence.

SAïD: Want to eat something? There’s the roast chicken in a corner of the valise.

THE MOTHER (gravely): You’re crazy, it’s for the meal. If a leg were missing, they’d think I raised crippled chickens. We’re poor, she’s ugly, but not enough to deserve one-legged chickens.

A silence.

SAïD: Won’t you put your shoes on? I’ve never seen you in high-heeled shoes.

THE MOTHER: I’ve worn them twice in my life. The first time, the day of your father’s funeral. Suddenly I was up so high I saw myself on a tower looking down at my grief that remained on the ground, where they were burying your father. One of the shoes, the left one, I found in a garbage can. The other, by the wash-house. The second time I wore them was when I had to receive the bailiff who wanted to foreclose on the shanty. (She laughs.) A dry ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Other Works By Jean Genet

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- The Characters

- Some Directions

- Scene One

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Screens by Jean Genet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.