- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

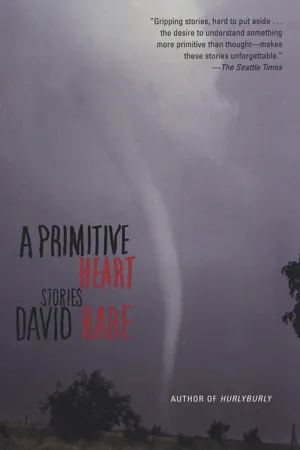

Tales from the Tony Award–winning playwright: "Not only an exhibition of David Rabe's acclaimed dramatic powers but also proof of his narrative magic" (Billy Collins, former US Poet Laureate).

David Rabe, playwright of Hurlyburly and In the Boom Boom Room, brings his intense vision to the world of fiction with a short story collection of astonishing range and versatility. Whether he is writing about a marriage shadowed by the unacknowledged discord of a risky pregnancy, a group of men whose attempt to settle an account launches them toward unexpected violence, or a young journalist who believes he's escaped his Catholic roots only to be forced again to confront them by a priest who once mentored his writing, Rabe's strong, true voice tenders an inimitable portrait of America and offers benediction to her lost souls. A Primitive Heart confirms the mastery of a writer and establishes David Rabe as an exciting voice in fiction.

"Rabe has a way of implicating the reader—of creating a near-claustrophobic bond with his restless characters, writing so convincingly that the subtext becomes almost palpable, accruing darkly, like a storm. Okay: I'm eating my heart out." —Ann Beattie, PEN/Malamud Award–winner

"These are gripping stories, hard to put aside, that cut so close to primitive emotional truths that they can be painful to read . . . That vivid confusion—the desire to understand something more primitive than thought—makes these stories unforgettable." — The Seattle Times

"David Rabe demonstrates in this new collection of short stories that his talent for dialogue is just as dazzling inside a prose narrative as it is on stage." — The Baltimore Sun

David Rabe, playwright of Hurlyburly and In the Boom Boom Room, brings his intense vision to the world of fiction with a short story collection of astonishing range and versatility. Whether he is writing about a marriage shadowed by the unacknowledged discord of a risky pregnancy, a group of men whose attempt to settle an account launches them toward unexpected violence, or a young journalist who believes he's escaped his Catholic roots only to be forced again to confront them by a priest who once mentored his writing, Rabe's strong, true voice tenders an inimitable portrait of America and offers benediction to her lost souls. A Primitive Heart confirms the mastery of a writer and establishes David Rabe as an exciting voice in fiction.

"Rabe has a way of implicating the reader—of creating a near-claustrophobic bond with his restless characters, writing so convincingly that the subtext becomes almost palpable, accruing darkly, like a storm. Okay: I'm eating my heart out." —Ann Beattie, PEN/Malamud Award–winner

"These are gripping stories, hard to put aside, that cut so close to primitive emotional truths that they can be painful to read . . . That vivid confusion—the desire to understand something more primitive than thought—makes these stories unforgettable." — The Seattle Times

"David Rabe demonstrates in this new collection of short stories that his talent for dialogue is just as dazzling inside a prose narrative as it is on stage." — The Baltimore Sun

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

HOLY MEN

THE GRAVEYARD SPILLED its markers over the ascending terrain in a glowing stream that made the moon emphatic. I had to look. The car, my father’s Ford, was dipping from a mild upgrade into a graceful bend where the absence of traffic allowed distraction. The moon was low and huge as I caught it through the barren crush of tree limbs that topped the nearest rise in the receding landscape. The rounded crest lay under piles of inky shadows from which the tombstones appeared to flow. Already, death was not far from my mind, because I was, after all, a former Catholic on my way to visit a priest. Certain associations are relentless. Still, it was not with the faintest grasp of anything unusual that I let my eyes absorb the display of mortality in its neatly tended monopoly of the vista. Boulders burst through the soil all over this part of Iowa due to the Mississippi forging its path long ago. Surrounding farms arranged the dirt in orderly rows of soy and corn amid gullies and bluffs, so it was ordinary for man-made patterns to mix with half-buried rocks. In memory those hillside markers hover like a schoolboy’s model of the Milky Way in the moon’s hard light, but that night I was past them quickly. I had driven that road hundreds of times, mostly as a teenager. My high school girlfriend had lived at the top of this same hill, and I had climbed to her often over these same curves I was now riding to visit Father Edward Lillius, a former teacher and mentor from whom I had been estranged for more than a dozen years.

What it was that urged me on this particular trip to break my silence and contact him I had no idea, nor have I any now. During this period of my life I traveled to my hometown with the furtiveness of a spy crossing the borders of a totalitarian state within whose confines I could be detained if my presence were detected. In spite of years away, a time in the army, and some success in the world, I remained wary of powers inherent in the place where I’d been a Catholic child. And yet several days earlier I had snatched up the phone in my parents’ living room. I remember a sensation of ill-considered risk as I dialed his number, even though I’d been struggling with the impulse, increasingly, as the days of my visit ticked past in their limited supply. His greeting had a reserved quality. And the pause into which I offered my name—“It’s me, Father. Mathew Nachtman”—vibrated with suspense. But then the formal reserve of his “Hello” melted when he said my name, “Mathew.” We spoke briefly, making arrangements to have dinner in his room a few evenings later, the night before I was to leave to fly back to New Haven, Connecticut, where I worked as a reporter. He didn’t like going out very much, he said, and hoped his room would not be too “abstentious, or sober.” The last word twinkled. Recognizing the pun, I vowed not to drink too much, hoping to forestall a threatening potential that lacked all specificity.

Leaving my car and strolling across the paved parking lot, I noted how the redbrick walls of Saint Martha’s Hall, a retirement home for nuns where Father Lillius was chaplain, rose only three stories, achieving the size necessary for its dormitory function by running lengthily along the hilltop. The front door opened on a narrow institutional void. I was immediately under the scrutiny of one of the nuns, an old woman seated at a table in an alcove off the main hallway. She was much like a desk clerk in a hotel except for her garb, the dark flowing habit crowned by the jowly oval of her face wrapped in a white cardboardlike frame that sustained the veil falling over the back of her head. Though the enclosing material was thinner and the veil softer than those I remembered from my school days, I still felt an old and familiar pang of alarm at the sight of her studying me. She was an earless smudge of glinting glasses, shoving aside the local newspaper. I gave my name, and she said, “Father’s been expecting you.” The look she left me with was a kind of tolerant reprimand, as if she knew secrets about me, most of which did not meet her approval. Rattling with rosaries large and small, she fled, only to return moments later to direct me to his room. I should go through the double doors straight ahead and then turn left. His was the first door on the right.

He appeared when I knocked, his rascal’s black eyes beaming and searching me for clues to the degree my present identity still harbored those traits he had thought prominent in my past. His glance was fierce as he foraged for something upon which to balance his claim of still knowing me well. In his priestly garb, he was a black wand of a man with curving black eyebrows and inky slicked-back hair combed flat in the manner of a silent movie screen idol. When he stepped back, our handshake prolonged, I saw a brief uncertainty undercut the brawn of his first emotion. It was a worry so fleeting I thought it best to ignore it as I turned away, thinking I would appear eager to examine his quarters. Whatever he might be feeling, I was stepping around it. Perhaps it was simply a wistful taste for the years that had skipped off without: us. Certainly, nostalgia could claim a place in these seconds. More for him than for me, but I could feel it, and it was not altogether welcome.

When he spoke, he had settled on a superficial point, though it touched the theme of difference between us. “You’ve gotten big,” he said, and he distorted the word, like a comic stripping away ordinary meaning so he could convey what he wanted. He was referring to my physical size. Thin through my college years, I was an emaciated wisp when I showed up in this room shortly after my discharge from the army. I assumed he was remembering that visit, which marked in my mind the end of my first attempt to separate from my past. During a five-year-long struggle following college, I traveled to the East Coast for graduate school, then quit and took random jobs, until I was drafted into the army, my communications with him growing sparse and artificial. The army took me to Vietnam for a year, and I returned under a spell of inwardness, my resources summoned to a crisis whose nature I can only suggest through some metaphoric exaggeration, such as a nail being driven through my brain.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, Father Lillius had been through his own tribulations during those same years, and to some extent they had been my fault. When I first met him, I was a nineteen-year-old sophomore, freshly introduced to the liberation I imagined available in creativity. Joining his creative writing class, I was a whirl of discovery and concomitant ambition, and by the end of that year he, as faculty moderator of our college literary magazine, named me editor.

I took over in the fall, and held the position as both a junior and a senior. Gradually, I pushed against the regulations that hemmed us in. Implicit upon most occasions, but blatant when necessary, they dictated what we could and could not write. We published twice a year, and my first response was to maneuver to expand the physical size of the magazine. Once this was under way, I sought to encourage material that might shove against the prohibitions insulating us, I felt, from ourselves. Given Father Lillius’s priestly vow of obedience, his intimacy with the official moral order, the administration considered him the only bulwark necessary to keep our minds and narratives properly sanitized, and so it was against him that I had to push. Not that he was content with things as they were, and not that the work we eventually produced could be judged daring by any standards other than those active in that precise time and place, the early 1960s at Creeger College.

I remember sitting with him one afternoon on stone steps near an empty athletic field with a book of e. e. cummings and a collection that included Dylan Thomas and Robert Lowell. Could they be published in our magazine? And if the answer was no, which it had to be, how could we expect to think of ourselves, or even aspire to think of ourselves, as artists? And Salinger! In a million years Salinger would not be allowed. Father Lillius shook his head and told me we couldn’t compare our efforts with those of such mature artists. But how we could even begin to try in our current circumstances I wanted to know. He reminded me that his duty was to help us develop first our moral principles and then our creativity. But wasn’t art our goal? I demanded. Catholic art, yes, but look at Graham Greene. His work was bold. Quoting cummings, I told him, “Nobody, not even the rain has such small hands,” and then I added Thomas: “After the first death there is no other.” Leafing pages, I threw in Lowell. “When the Lord God formed man from the sea’s slime.” Perhaps because I knew my points were less than infallible, I was energetic. Eventually, when he wavered, it was to allow that we would broaden what we explored in his class, but the established codes would still determine what we published.

Over the next semesters, however, since my desire to transform the magazine was in fact a desire to transform myself, I persisted, as did his class. It may have been that our work in this new atmosphere beguiled him. Previously forbidden feelings from our daily lives, our secrets, our dreams, even some representative darkness appeared as we sat with him around our table and read aloud what we had written. Boys and girls touched and were tempted by sinful pleasure and felt bereft without it. Adults were not always saintly. Dark figures prowled the horizon with hints of alluring powers.

Regularly, he carried our stories and poems back to his room where he corrected our sentences, marking mistakes, offering his seer criticism with his very blue pencil. I believe it was this prolonged intimacy with our developing themes, our chance encounter with moments of truth that led him to modify his perspective. Did he feel left out? Maybe. I remember a Salingeresque tale full of innuendo and governed by enigmatic exchanges between two girls that intrigued him and found its way into the magazine. Then came another whose overripe prose could not bring to light its issues, though the weight of the sentences led one by one to the suggestion that the unmarried girl at the center was pregnant. And while it must be said that little we produced fully escaped being quaintly adolescent and naive, still we tasted authenticity for we were operating at a point in our psyches nearer our actual selves than we had ever gone before.

Gradually, he shifted toward us, until the desire to join what we were doing took hold of him. When willingness followed, Father Lillius, intended to be our censor, became our cohort. By the start of my senior year he relished our subversive project, urging us on with impish delight, until finally he took the boldest step and became a participant. Using a pseudonym, he began to publish in our pages. As “Edward Demmer Demwolf,” his poetry ventured up to the proprietary margins and then beyond until, in his gossamer and made-up persona, he was afloat outside the comportment expected of his priestly reality.

Now we knew that while he was our watchman, there were others watching him. But our faith in our cleverness was exceeded only by our belief that we were right. And so it happened that in the spring of my senior year, the enterprise we deemed our freedom crossed into a realm where our mutinous aims were expressed too blatantly. It was in my last issue as editor that we playfully overstepped by identifying Edward Demmer Demwolf as a “poet/philosopher.” After inventing a lengthy biography, we named him author of a poem by Father Lillius hazy with spring references to fecundity, along with an essay written by a student espousing beatnik anarchy. Like small boys poking a snake with a stick we cavalierly taunted our superiors, only to rouse the wrath of an adversary we had not taken into account for we had not known he was there chaffing at our transgressions all along. He was in the Philosophy Department, a professor nicknamed the Loon, and for this shrewd, volatile man our use of the title “philosopher” regarding our fictional comrade was a sacrilege. He erupted, declaring Edward Demmer Demwolf no philosopher and condemning both his poem and his essay as degenerate screeds. Stirred by his cries, others looked where he was pointing, his accusations shining all the light they needed to shove aside our stealth.

Father Lillius probably knew that such a moment must arrive. Even as he let himself be drawn into our venture, he probably understood the risk. Still, I doubt that even his most pessimistic conjectures suggested anything that remotely resembled the bitter retribution that came. Certainly nothing depicted in our shyly disillusioned prose or lyrical sonnets or existential blank verse approached the dark reality we unleashed. Largely our miscalculation sprang from the fact that while I had cheered him past his reservations, I was unreliable. Ignorance guided me more than real courage. Seeking to eliminate my own repressive traits, I mistook my desires for those of everyone around me including the hierarchy against which I strained. Hidden within my icono-clasm was the belief that my rebellion was supported, if only secretly, by those who stood above me in the role of oppressor, because the liberation I anticipated would be theirs also.

I graduated that spring amid some confusion, the mounting uproar suspended. By the time it returned full-blown, I was gone. But Father Lillius wasn’t. Quickly, the magazine was disbanded, its diminutive replacement managed by a doctrinaire moderator who published only what the president of the college read and approved. Father Lillius was brought before his superiors. It was suggested that his character and capabilities were flawed. Squalid innuendo thickened into accusations of dereliction and then even moral impropriety. He was hounded and threatened. The more reasonable his defense, the more audacious grew his accusers. Soon they began to gossip on the likelihood that he had not merely tolerated but had inspired our corruption. In the end, he had a nervous breakdown.

I was far away by then, making of distance and silence a fortification behind which I could try to change. I wanted out of everything, the church most of all, but my impractical and trusting sensibility was also to be remodeled or annihilated. As a result, I was not around when Father Lillius attempted suicide, and was institutionalized, and after a period of treatment returned to the corridors of the college with his doctor, a psychiatrist, at his side, vouching for his recovery and petitioning for his right to return to the classroom. The college president, Father Prunty, informed the doctor that under no circumstances would Father Lillius ever be allowed to teach again. When the doctor argued, producing data and documentation, Father Prunty declared that his decision was divinely guided. Father Lillius could not be trusted with the vulnerable students it was the college’s mission to shepherd. He would be banished to Saint Martha’s Hall, this building on the hill where he would serve as chaplain to aging nuns.

When I first heard of his suicide attempt, it was years in the past, from which I was once again disaffected. With the army behind me, I was sequestered in the East. My best estimate placed his despairing gesture in the period when I was in Vietnam. Still, I believed my defection had contributed to the momentum that bore him to that cold juncture, then dropped him off. Guilt brought on a threatening regression whose only counteraction was to escalate the severity and terms of my quarantine. Fearing that my absence, and more explicitly my silence, had loomed to prod him on, I withdrew further, as if like the others in the jeering mob I had come to hate him.

Now I stood before him, registering his first words: “You’ve gotten big.” He was right that heft had accumulated on me, a thickening armament behind which I awaited the final sutures in the surgery of my uncertain transformation. Still, I was slightly miffed. I had opposed this change, dieting intermittently and exercising often, and I thought any fair-minded assessment would find that I had largely succeeded.

“No, no,” he said to soothe me. “I mean, thick.”

I laughed both to ridicule my vanity and to eliminate the apology it seemed he was feeling, as I followed the sweep of his arm into the room.

“Hardly luxurious—still I find it more than sufficient,” he smiled.

Looking around, I said, “It seems fine.”

“That Hemingway word.” His grin split his face in a bursting curve that went almost literally from ear to ear. His eyes flashed. “What are you drinking these days?”

“I have to travel first thing in the morning,” I said, intending to let him know that I wasn’t going to drink a lot. “I think I better be home by eleven.”

“Don’t start talking about leaving. You just got here. Holy Mary pray for us. I’m having scotch. Speak up or scotch is what you will get too.”

“Scotch will be okay.”

“Good. How will I ever plumb your secrets unless I first ply you with liquor?”

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” I smiled, watching him lift a half-full fifth of Black Label from a built-in cabinet below some bookshelves. I felt awkward, standing in the middle of that room, wondering why I’d made the call that had brought me there when I could have simply, smartly fled. Occupying bookshelves and tabletops and dangling from walls, many and varied objects stilled from the vortex of his life had been arranged in a willful conception. On a windowsill three lilies, each in its own trumpeting vase, stood before the backdrop of the gray pane holding against the night. Numerous photos, mostly of former students, were on display, along with several Japanese prints. Near the entrance hung a portrait of the Sacred Heart, the Christ with a surgically sprung flap to reveal a burning, gleaming orb. On one of the panels between the windows...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- A Primitive Heart

- Early Madonna

- Some Loose Change

- Veranda

- Holy Men

- Leveling Out

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Primitive Heart by David Rabe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Literatura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.