- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

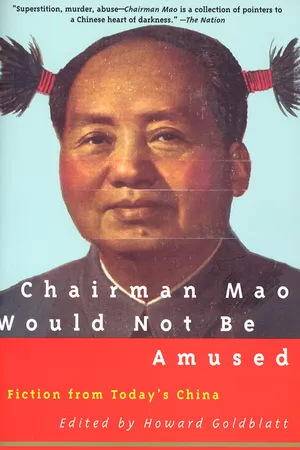

Stories by Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan, Booker Prize winner Su Tong, and more: "Takes readers into worlds the Chinese government has long tried to hide."—

The Washington Post Book World

"In contrast to the utopian official literature of Communist China, the stories in this wide-ranging collection marshal wry humor, entangled sex, urban alienation, nasty village politics and frequent violence…'The Brothers Shu,' by Su Tong ( Raise the Red Lantern), is an urban tale of young lust and sibling rivalry in a sordid neighborhood around the ironically named Fragrant Cedar Street. That story's earthiness is matched by Wang Xiangfu's folksy 'Fritter Hollow Chronicles,' about peasants' vendettas and local politics, and by 'The Cure,' by Mo Yan ( Red Sorghum; The Garlic Ballads), which details the fringe benefits of an execution. Personal alienation and disaffection are as likely to appear in stories with rural settings (Li Rui's 'Sham Marriage') as they are to poison the lives of urban characters (Chen Cun's 'Footsteps on the Roof'). Comedy takes an elegant and elaborate form in 'A String of Choices,' Wang Meng's tale of a toothache cure, and it assumes the burlesque of small-town propaganda fodder in Li Xiao's 'Grass on the Rooftop.'"— Publishers Weekly

"Fiction that reflects the turmoil brought about by Tiananmen and the money-making ethic found in China today."— Library Journal

Includes contributions by Shi Tiesheng, Hong Ying, Su Tong, Wang Meng, Li Rui, Duo Duo, Chen Ran, Li Xiao, Yu Hua, Mo Yan, Ai Bei, Cao Naiqian, Can Xue, Bi Feiyu, Yang Zhengguang, Ge Fei, Chen Cun, Chi Li, Kong Jiesheng, Wang Xiangfu

"In contrast to the utopian official literature of Communist China, the stories in this wide-ranging collection marshal wry humor, entangled sex, urban alienation, nasty village politics and frequent violence…'The Brothers Shu,' by Su Tong ( Raise the Red Lantern), is an urban tale of young lust and sibling rivalry in a sordid neighborhood around the ironically named Fragrant Cedar Street. That story's earthiness is matched by Wang Xiangfu's folksy 'Fritter Hollow Chronicles,' about peasants' vendettas and local politics, and by 'The Cure,' by Mo Yan ( Red Sorghum; The Garlic Ballads), which details the fringe benefits of an execution. Personal alienation and disaffection are as likely to appear in stories with rural settings (Li Rui's 'Sham Marriage') as they are to poison the lives of urban characters (Chen Cun's 'Footsteps on the Roof'). Comedy takes an elegant and elaborate form in 'A String of Choices,' Wang Meng's tale of a toothache cure, and it assumes the burlesque of small-town propaganda fodder in Li Xiao's 'Grass on the Rooftop.'"— Publishers Weekly

"Fiction that reflects the turmoil brought about by Tiananmen and the money-making ethic found in China today."— Library Journal

Includes contributions by Shi Tiesheng, Hong Ying, Su Tong, Wang Meng, Li Rui, Duo Duo, Chen Ran, Li Xiao, Yu Hua, Mo Yan, Ai Bei, Cao Naiqian, Can Xue, Bi Feiyu, Yang Zhengguang, Ge Fei, Chen Cun, Chi Li, Kong Jiesheng, Wang Xiangfu

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chairman Mao Would Not Be Amused by Howard Goldblatt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Brothers Shu

The story of Fragrant Cedar Street is legendary among people in my hometown. In the south of China, there are lots of streets just like it: narrow, dirty, the cobblestones forming a network of potholes. When you look out your window at the street or at the river’s edge, you can see dried meat and drying laundry hanging from eaves, and you can see inside houses, where people are at the dinner table or engaged in a whole range of daily activities. What I am about to give you isn’t so much a story as it is a word picture of life down south, and little more.

The brothers Shu Gong and Shu Nong lived on that particular street.

So did the Lin sisters, Hanli and Hanzhen.

They shared a building: 18 Fragrant Cedar Street, a blackened two-story structure, where the Shu family lived downstairs and the Lins above them. They were neighbors. Black sheet metal covered the flat roof of number 18, and as I stood at the bridgehead, I saw a cat crouching up there. At least that’s how I remember it, fifteen years later.

And I remember the river, which intersected Fragrant Cedar Street a scant three or four feet from number 18. This river will make several appearances in my narration, with dubious distinction, for as I indicated earlier, I can only give impressions.

Shu Gong was the elder son, Shu Nong his younger brother.

Hanli was the elder daughter, Hanzhen her younger sister.

The ages of the Shu brothers and Lin sisters can be likened to the fingers of your hand: if Shu Nong was fourteen, then Hanzhen was fifteen, Shu Gong sixteen, and Hanli seventeen. A hand with four fingers lined up so tightly you can’t pry them apart. Four fingers on the same hand. But where is the thumb?

Shu Nong was a timid, sallow-faced little devil. In the crude and simple classroom of Fragrant Cedar Middle School, he was the boy sitting up front in the middle row, dressed in a gray school uniform, neatly patched at the elbows, over a threadbare hand-me-down shirt with a grimy blue collar. The teachers at Fragrant Cedar Middle School all disliked Shu Nong, mainly because of the way he sprawled across his desk and picked his nose as he stared up at them. Experienced teachers knew he wasn’t listening, and if they smacked him over the head with a pointer, he shrieked like splintered glass and complained, “I wasn’t talking!” So while he wasn’t the naughtiest child in class, his teachers pretty much ignored him, having taken all the gloomy stares from his old-man’s eyes they could bear. To them, he was “a little schemer.” Plus he usually smelled like he had just peed his pants.

Shu Nong was still wetting the bed at fourteen. And that was one of his secrets.

At first, we weren’t aware of this secret. It was Hanzhen who let the cat out of the bag. Devoted to the act of eating, Hanzhen had such a greedy little mouth she even stole from her parents to buy snacks. One day when there was nothing to steal and she was standing outside the sweetshop looking depressed, Shu Nong happened by, dragging his schoolbag behind him. She stopped him: “I need twenty fen.” He tried to walk around her, but she grabbed the strap of his bag and wouldn’t let him pass. “Are you going to lend it to me or not, you little miser?” she demanded.

Shu Nong replied, “All I’ve got on me is two fen.”

Hanzhen frowned and casually slapped him with his own strap. Then, jamming her fists onto her hips, she said, “Don’t you kids play with him. He wets the bed. His sheets are hung out to dry every day!”

I watched her spin around and take off toward school, leaving Shu Nong standing motionless and gloomy, holding his face in his hands as he followed her pudgy figure with his eyes. Then he looked at me—gloom filled his eyes. I can still see that fearful look on his fourteen-year-old face, best described as that of a young criminal genius. “Let’s go,” I said. “I won’t tell anybody.”

He shook his head, jammed his finger up his nose, and dug around a bit. “You go ahead. I’m skipping school today.”

Shu Nong played hooky a lot, so that was no big deal. And I assumed he was already cooking up a way to get even with Hanzhen, which also was no big deal since he had a reputation for settling scores.

On the very next day, Hanzhen came into the office to report Shu Nong for putting five dead rats, some twisted wire, and a dozen or more thumbtacks in her bed. The teachers promised to punish him, but he played hooky that day, too. On the day after that, Hanzhen’s mother, Qiu Yumei, came to school with a bowl of rice and asked the principal to smell it. He asked what was going on. Qiu Yumei accused Shu Nong of peeing in her rice pot. A crowd was gathering outside the office when the gym teacher dragged in Shu Nong, who had sauntered in to school only moments earlier and flung him into the corner.

“Here he is,” the principal said. “Now what do you want me to do?”

“That’s easy,” Qiu Yumei replied. “Make him eat the rice, and he’ll think twice about doing that again.”

After mulling the suggestion over for a few seconds, the principal carried the offending bowl of rice over to Shu Nong. “Eat up,” he said, “and taste the fruit of your labors.”

Shu Nong stood there with his head down, hands jammed into his pockets as he nonchalantly fiddled with a key ring. The sound of keys jangling in the boy’s grimy pocket clearly angered the principal, who in plain view of everyone, forced Shu Nong’s head down over the rice. Shu Nong licked it almost instinctively, then yelped like a puppy, and spat the stuff out. Deathly pale, he ran out of the office, a single kernel of rice stuck to the corner of his mouth. The bystanders roared with laughter.

That evening, I spotted Shu Nong at the limestone quarry, wobbling across the rocky ground, dragging his schoolbag behind him. He picked an old tree limb out of a pile of rubbish and began kicking it ahead of him. He looked as gloomy and dejected as always. I thought I heard him announce, “I’ll screw the shit out of Lin Hanzhen.” His voice was high-pitched and shrill but as flat and emotionless as a girl saying to a clerk in a sweetshop, I’d like a candy figurine, please. “And I’ll screw the shit out of Qiu Yumei!” he added.

A male figure climbed onto the roof of number 18. From a distance, it looked like a repairman. It was Shu Nong’s father. Since the neighbors all called him Old Shu, that’s what we’ll call him here. To members of my family, Old Shu was special. I remember him as a short, stocky man who was either a construction worker or a pipe fitter. Whichever, he was good with his hands. If someone’s plumbing leaked or the electric meter was broken, the lady of the house would say, “Go find Old Shu.” He wasn’t much to look at, but the women on Fragrant Cedar Street liked him. In retrospect, I’d have to say Old Shu was a ladies’ man, of which Fragrant Cedar Street boasted several, one of whom, as I say, was Old Shu. That’s how I see it, anyhow.

Let’s say that some women doing their knitting see Old Shu on the roof of number 18. They start gossiping about his amorous escapades, mostly about how he and Qiu Yumei do this, that, and the other. I recall going into a condiments shop once and overhearing the soy sauce lady tell the woman who sold pickled vegetables, “Old Shu is the father of the two Lin girls! And look how that trashy Qiu Yumei struts around!” The condiments shop was often the source of shocking talk like that. Qiu Yumei was walking past just then but didn’t hear them.

If you believed the women’s brassy gossip, one look at Lin Hanzhen’s father would strengthen your conviction. What did Old Lin do for a living? you ask. Let’s say it’s a summer day at sunset, and a man is playing chess in the doorway of the handkerchief maker’s. That will be Old Lin, who plays there every day. Sometimes Hanzhen or Hanli brings his dinner and lays it next to the chessboard. Old Lin wears thick glasses for his nearsightedness. He has no special talents, but once after losing a chess game, he popped the cannon piece into his mouth and would have swallowed it if Hanli hadn’t pried open his mouth and plucked it out. She knocked over the chessboard, earning herself a slap in the face. “You want to keep playing?” she complained tearfully with a stomp of her foot. “I should have let you swallow that piece!”

Old Lin retorted, “I’ll swallow whatever I want to swallow, and you can just butt out!”

People watching the game laughed. They got a kick out of Old Lin’s temper. They also got a kick out of Hanli, because she was so pretty and had such a good heart. The neighbors were unanimous in their appraisal of the sisters: they liked Hanli and disliked Hanzhen.

Now all the players in our drama have made an appearance, all but Shu Gong and his mother, that is. There isn’t much to be said about the woman in the Shu family. Craven and easily intimidated, she padded like a mouse around the downstairs of number 18, cooking meals and washing clothes, and I have virtually no recollection of her. Shu Gong, on the other hand, is very important, since for a time he was an object of veneration among young people on Fragrant Cedar Street.

Shu Gong had a black mustache, an upside-down V sort of like Stalin’s.

Shu Gong had delicate features and always wore a pair of white Shanghai-made high-top sneakers.

Shu Gong had been in a gang fight at the limestone quarry with some kids from the west side, and he had had a love affair. Guess who he had the affair with.

Hanli.

In retrospect, I can see that the two families at number 18 had a very interesting relationship.

Shu Gong and Shu Nong shared a bed at first and fought night after night. Shu Gong would come roaring out of a sound sleep and kick Shu Nong: “You wet the bed again, you wet the goddamned bed!” Shu Nong would lie there not making a sound, eyes open as he listened for the prowling steps and night screeches of the cat on the roof. He got used to being kicked and slugged by his brother since he knew he had it coming. He always wet the bed, and Shu Gong’s side was always clean as a whistle. Besides, he was no match for Shu Gong in a fight. Knowing how reckless it would be to stand up to his brother, Shu Nong let strategy be his watchword. He recalled the wise comment someone made after being beaten up one day on the stone bridge: a true gentleman gets revenge, even if it takes ten years. Shu Nong understood exactly what that meant. So one night after Shu Gong had kicked and slugged him again, he said very deliberately, “A true gentleman gets revenge, even if it takes ten years.”

“What did you say?” Shu Gong, who thought he was hearing things, crawled over and patted Shu Nong’s face. “Did you say something about revenge?” He smirked. “You little shit, what do you know about revenge?”

His brother’s lips flashed in the darkness like two squirming maggots. He repeated the comment.

Shu Gong clapped his hand over his brother’s mouth. “Shut that stinky mouth of yours, and go to sleep,” he said, then found a dry spot in bed and lay back down.

Shu Nong was still mumbling. He was saying, “Shu Gong, I’m going to kill you.”

Shu Gong had another chuckle over that. “Want me to go get the cleaver?”

“Not now,” Shu Nong replied. “Some other day. Just don’t turn your back.”

Years later, Shu Gong could still see Shu Nong’s pale lips flashing in the dark like a couple of squirming maggots. But back then, he could no longer endure sharing a bed with Shu Nong, so he told his parents, “Buy me a bed of my own, or I’ll stay with a friend and forget about coming home.”

Old Shu was momentarily speechless. “I see you’ve grown up,” he said as he lifted his son’s arm to look at his armpit. “OK, it’s starting to grow. I’ll buy you a real spring bed tomorrow.”

After that, Shu Nong slept alone. He was still fourteen.

At the age of fourteen, Shu Nong began sleeping alone. He vowed on his first night away from his brother never to wet the bed again. Let’s say that it’s an autumn night forgotten by all concerned and that Shu Nong’s dejection is like a floating leaf somewhere down south. He lies wide awake in the darkness, listening to the surpassing stillness outside his window on Fragrant Cedar Street, broken occasionally by a truck rumbling down the street, which makes his bed shake slightly. It’s a boring street, Shu Nong thinks, and growing up on it is even more so. His thoughts fly all over the place until he gets sleepy, but as he curls up for the night, Shu Gong’s bed begins to creak and keeps on creaking for a long time. “What are you doing?”

“None of your business. Go to sleep, so you can wet your bed,” Shu Gong snaps back spitefully.

“I’m not wetting my bed anymore.” Shu Nong sits up straight. “I can’t wet it if I don’t sleep!”

No response from Shu Gong, who is by now snoring loudly. The sound disgusts Shu Nong, who thinks Shu Gong is more boring than anything, an SOB just begging to get his lumps. Shu Nong looks out the window and hears a cat spring from the windowsill up to the roof. He sees the cat’s dark-green eyes, flashing like a pair of tiny lamps. No one pays any attention to the cat, which is free to prance off anywhere in the world it likes. To Shu Nong, being feline seems more interesting than being human.

That is how Shu Nong viewed the world at fourteen: being feline is more interesting than being human.

If the moon is out that night, Shu Nong is likely to see his father climbing up the rainspout. Suddenly, he sees someone climbing expertly up the rainspout next to the window like a gigantic house lizard. Shu Nong experiences a moment of fear before sticking his head out the window and grabbing a leg.

“What do you think you’re doing?” That is exactly how long it takes him to discover it is his father, Old Shu, who thumps his son on the head with the sandal in his hand. “Be a good boy, and shut up. I’m going up to fix the gutter.”

“Is it leaking?”

“Like a sieve. But I’ll take care of it.”

Shu Nong says, “I’ll go with you.”

With a sigh of exasperation, Old Shu shins down to the windowsill, squats in his bare feet, and wraps his hands around Shu Nong’s neck. “Get back to bed, and go to sleep,” Old Shu says. “You saw nothing, unless you want me to throttle you. And don’t think I won’t do it, you understand?”

His father’s hands around his neck feel like knives cutting into his flesh. He closes his eyes, and the hands fall loose. He sees his father grab hold of something, spring off the sill, and climb to the top floor.

After that, Shu Nong goes back and sits on his bed, but he isn’t sleepy. He hears a thud upstairs in Qiu Yumei’s room, then silence. What’s going on? Shu Nong thinks of the cat. If the cat’s on the roof, can it see what Father and Qiu Yumei are up to? Shu Nong thought a lot about things like that when he was fourteen. His thoughts, too, are like leaves floating aimlessly somewhere down south. Just before dawn, a rooster crows somewhere, and Shu Nong realizes he had fallen asleep—and had wet the bed. Mentally he wrings out his dripping-wet underpants, and the rank smell of urine nearly makes him gag. How could I have fallen asleep? How come I wet the bed again? His nighttime discovery floats up like a dream. Who made me go to sleep? Who made me wet the bed? A sense of desolation wraps itself around Shu Nong’s heart. He slips off his wet pants and begins to sob. Shu Nong did a lot of sobbing at the age of fourteen, just like a little girl.

Shu Nong asked me a really weird question once, but then he was always asking weird questions. And if you didn’t supply a satisfying answer, he’d give you a reasoned reply of his own.

“What’s better, being human or being a cat?”

I said human, naturally.

“Wrong. Cats are free, and nobody pays them any attention. Cats can prowl the eaves of a house.”

So I said, “Go be a cat, then.”

“Do you think people can turn into cats?”

“No. Cats have cats, people have people. Don’t tell me you don’t even know that!”

“I know that. What I mean is, Can someone turn himself into a cat?”

“Try it, and see.”

“Maybe I will. But I have lots to do before that. I’m going to make you all sit up and take notice.” Shu Nong began chewing his grubby fingernails, making a light clipping n...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Howard Goldblatt Introduction

- Shi Tiesheng First Person

- Hong Ying The Field

- Su Tong The Brothers Shu

- Wang Meng A String of Choices

- Li Rui Sham Marriage

- Duo Duo The Day I Got to Xi’an

- Chen Ran Sunshine Between the Lips

- Li Xiao Grass on the Rooftop

- YU Hua The Past and the Punishments

- Mo Yan The Cure

- Ai Bei Green Earth Mother

- Cao Naiqian When I Think of You Late at Night, There’s Nothing I Can Do

- Can Xue The Summons

- Bi Feiyu The Ancestor

- Yang Zhengguang Moonlight over the Field of Ghosts

- Ge Fei Remembering Mr. Wu You

- Chen Cun Footsteps on the Roof

- Chi Li Willow Waist

- Kong Jiesheng The Sleeping Lion

- Wang Xiangfu Fritter Hollow Chronicles

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgments

- Footnotes