- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

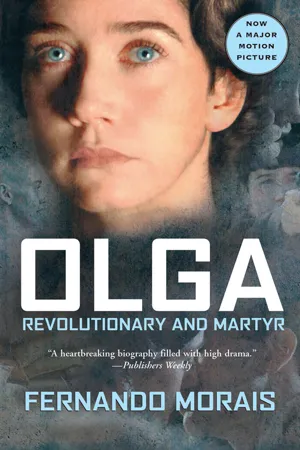

This "heartbreaking biography" of the Communist revolutionary "is filled with high drama," daring escapes, and eventual imprisonment in Nazi Germany (

Publishers Weekly).

A German-born Jew, Olga Benario was one of the most remarkable Communist activists of the twentieth century. With a genius for organization and an unwavering devotion, she crisscrossed the globe educating and activating legions to combat the worldwide plagues of Nazism and fascism. At the age of nineteen, she masterminded a daring prison raid to free her lover, the Communist intellectual Otto Braun. Together they escaped to Moscow, where they quickly rose in the ranks of the international Communist movement.

At twenty-six, Benario was chosen to serve as bodyguard to the legendary Brazilian guerrilla leader Luis Carlos Prestes, who had been brought to Moscow for training and would soon become her new lover. Traveling under assumed names, they crossed Europe and North America to reach Brazil, where Prestes would launch a revolution against the fascist regime. But tragically, within months, they were seized by police.

From Brazil, Olga, then seven months pregnant, was deported to Nazi Germany. She was subsequently sent to Ravensbruck concentration camp, and in February 1942 she was sent to her death in the gas chambers at Bernburg.

A German-born Jew, Olga Benario was one of the most remarkable Communist activists of the twentieth century. With a genius for organization and an unwavering devotion, she crisscrossed the globe educating and activating legions to combat the worldwide plagues of Nazism and fascism. At the age of nineteen, she masterminded a daring prison raid to free her lover, the Communist intellectual Otto Braun. Together they escaped to Moscow, where they quickly rose in the ranks of the international Communist movement.

At twenty-six, Benario was chosen to serve as bodyguard to the legendary Brazilian guerrilla leader Luis Carlos Prestes, who had been brought to Moscow for training and would soon become her new lover. Traveling under assumed names, they crossed Europe and North America to reach Brazil, where Prestes would launch a revolution against the fascist regime. But tragically, within months, they were seized by police.

From Brazil, Olga, then seven months pregnant, was deported to Nazi Germany. She was subsequently sent to Ravensbruck concentration camp, and in February 1942 she was sent to her death in the gas chambers at Bernburg.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Olga by Fernando Morais, Ellen Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Inside the Red Fort

OLGA AND OTTO arrived at the Hotel Desna in Moscow, exhausted after seventy-two hours on the train. In contrast to the Hotel Lux, designed for illustrious foreigners, the Desna wasn’t the least bit ostentatious, though it was, on the other hand, clean and discreet. As she registered, Olga noticed the curious coincidence that five years ago to the day she had first joined a Communist organization.

That had been in the summer of 1923, in her native city of Munich, just a few months before her fifteenth birthday. Banned by the police, the Communist Youth had gone underground. Its most militant members—eighteen years old and under—had created the Schwabing Group, which met once a week in an old sawmill in the suburbs of the Bavarian capital. One afternoon the meeting was interrupted by suspicious noises outside. Those in charge of security investigated, fearing the arrival of the police. Instead they found a tall, lanky girl with dark braids who demanded to become a member. Once inside the sawmill, Olga was closely questioned by the group’s leader. When asked her address and her parents’ names, she responded, “My father is Leo Benario, a lawyer. But that’s not my fault.”

For the majority of German Communists, the Right was not the only enemy. Social Democrats were placed in the same category and treated with the same disdain—and Benario was a Social Democrat. So, for the Schwabing Group, Olga’s was an unexpected presence. Never until then had a young person from the conservative Bavarian bourgeoisie knocked at the door.

Their prejudice was unjustified. Though one of the most respected jurists in the state and an influential personality in the local Social Democrat Party, Jewish lawyer Leo Benario was a liberal with progressive ideas. Olga herself would one day say that her own conversion to communism had not been the result of reading Marxist theory but of thumbing through the cases of those working-class clients her father represented. “In those files, I saw close up the poverty and injustice that I was only superficially acquainted with from books,” she would say.

In contrast to the considerable respect she had for her father, Olga’s infrequent comments about her mother were marked by coolness and brevity. The product of a well-to-do Jewish family, Eugenie Gutmann Benario was an elegant high-society lady who regarded with horror the prospect of her daughter becoming a Communist. Olga’s maternal grandmother was an even less important presence in her life. All Olga remembered of her was the bantam hen her grandmother presented her with during the depression that accompanied the Great War—a prosaic but useful gift in a time when eggs were rationed—and the question that was the old woman’s response to any news of the world brought to her by her granddaughter, as if a prediction of the tragedy to befall Germany: “Just tell me—is it good or bad for Jews?”

Olga never concealed the affection she felt for her father. He was a middle-class Social Democrat—but with an important difference. Workers who wanted to make judicial claims against their employers but couldn’t afford the services of a lawyer invariably came to Benario for help. He accepted whatever they could pay him and worked free for those who could pay him nothing. “Even more diligently than for the paying customers,” Olga recalled. Observing the clientele that frequented the family’s elegant home on Karlplatz, Olga grew more and more interested in their plight. The stream of people who passed through her father’s office every day— often discussing their problems in front of the young girl—ran the gamut from the wealthiest to the most poverty-stricken inhabitants of Munich. “The class struggle visited me daily,” she joked.

There certainly was no lack of clients, many of whom were badly affected by the dramatic economic situation that had been eating away at Germany since the end of World War I. The brutal inflationary spiral had reached such an extreme that the dollar, which in mid-1922 was worth a thousand marks, cost 350 million marks just one year later. Diligent working-class Germans were on the brink of destitution and the middle class was rapidly becoming the proletariat. The apparent lack of a solution to the crisis had led labor unions, the majority of which were controlled by Communists and Social Democrats, to lose power along with the working-class population. Olga believed that she had found the answer, at least her own personal answer: she dedicated herself more and more fully to the Communist cause. In the first job assigned to her during that summer of 1923, she demonstrated to the young people of Schwabing that their newest member was no bored bourgeois teenager. As part of a clandestine crew putting up posters, Olga proved to be the most efficient of the team, which included older and stronger members. Efficient and daring: for the first time, not only the suburbs of Munich but the center as well woke to find their streets blanketed with posters. Olga had covered even the busiest areas, where the police presence frightened off the most experienced of militants. “Fear and caution are simply not in her vocabulary,” said her new friends the following day.

Before long Olga was an integral part of Schwabing. Along with courage and determination, she brought from her upbringing something the sons and daughters of the working class lacked—an excellent education. She had actually read many of the Marxist classics that the majority of them had only heard about in lectures. They soon noticed another vivid characteristic—one that those most resistant to her presence in Schwabing attributed to the “radicalism peculiar to products of the bourgeoisie”: intolerance of anyone who wasn’t a militant Communist. She was warned innumerable times by older members to avoid behavior that was little more than childish provocation, such as walking down the street brazenly sporting a red brooch bearing the hammer and sickle.

Olga first heard of Professor Otto Braun toward the end of 1923, when she was working as an assistant in Georg Müller’s bookshop. She began fantasizing about him just from his description— especially as reported by women—weaving a myth about young, handsome, intelligent Otto, who, it was whispered, worked secretly as a Soviet agent. When, finally, a mutual friend arranged for the two to meet, Olga was surprised. Her picture of Otto had been a caricature of a revolutionary: a ragged beard, fatigues, and long, disheveled hair. The Otto that sat across from her in the café smoking a pipe was actually quite polished: tie meticulously straight, hair neatly parted and fixed in place with hair tonic, crisply creased trousers, and brushed suede boots.

Though only twenty-two, seven years older than she, Otto was an experienced militant, even in the area that most fascinated Olga: armed action. During the frustrated popular revolution of 1919 (an attempt to repeat the Russian phenomenon of two years earlier), the Party had sent him on a secret mission to intercept a convoy of troops dispatched by the central government to retake Munich, then capital of the “Republic of Bavaria.” The mission itself was a success and Munich resisted for more than a month longer, with Otto at the head of a group of combatants. The government, however, sent wave after wave of reinforcements to battle with the insurgents and finally retook the city. In spite of the outcome, Otto prided himself on having wiped out so many “right-wing Social Democrats.” The battle of Munich ended with Otto in prison—his first and shortest incarceration.

Otto and Olga began seeing each other, their mutual fascination growing by the day. She imagined she had found the perfect man, someone who managed to combine a solid theoretical background with military experience. Not to mention the fact that he was very handsome. And Otto was clearly charmed by the half-girl, half-woman who thirsted for both theory and action like no one he’d ever met. Half an hour before her duties at the bookshop were over, he would appear with his pipe and elegant scarf, ready for conversation that stretched into the small hours of the morning.

Otto began to direct Olga’s reading and to suggest, in addition to the theoretical works indispensable to her understanding of communism, various magazines and journals published by Marxist groups in Berlin. He was amazed by her insistent requests for manuals on military strategy, written statements by great generals, and reports of famous battles. The militant behind those soft blue eyes would emerge at Schwabing meetings, frequently criticizing the group’s lack of interest in military techniques and the absence of regular training for all militants. Olga’s quarrels with the young men in the group only became really serious, though, when she realized that on the basis of gender she was being assigned secondary duties. At the end of one such disagreement, she grumbled for all to hear: “I want you to know that at times like this it’s a pain to be a woman.”

The more she pored over the Marxist classics and the more she militated at Schwabing, the firmer became Olga’s conviction that she should leave Munich for Berlin. The refined and perfumed clientele at Müller’s bookshop, the arguments with her parents, her very home itself were becoming unbearable. News of political turmoil reported in Berlin newspapers inflamed her imagination. Olga’s fantasy of life in the capital had a name: Neukölln, the working-class district in Berlin known by the German Left as “the Red Fort.” After months of insistently badgering Otto, she finally got her way. It was late one afternoon, as they walked hand in hand in a park outside Munich. He himself seemed unsure of the arrangements.

“I’ve consulted the Party and it looks feasible for us to move to Berlin. But what about your family? How will you persuade your father to accept the idea?”

The question made her furious.

“I’m on my way the minute the Party gives us the go-ahead!”

In fact, it was not just politics that were pushing Olga toward Berlin. She was in love with Otto. Weekends spent together in snow-covered cabins had revealed the sweet, tender, patient man behind the sober professor of Marxism. The idea of spending her days among the young Communist workers of Neukölln and her nights with Otto was everything that Olga Gutmann Benario desired at that time.

Only after she had the second-class train ticket in her hand and her small suitcase packed and ready did she inform her parents that she was leaving that very evening. Dinner was silent. Her mother chose to stay upstairs. Olga valiantly tried to avoid a fight with her father. After three hours of discussion, she got up to leave. Leo’s good-bye kiss at the door told her that deep inside, he knew that in her place he might be doing the same thing.

Twenty-four hours later, from the window of her room in the attic of a small two-story house, Olga gazed down at Weser Street: so, she was really here, in the heart of Neukölln. To someone who had spent her childhood and adolescence in the comfortable Benario home on Karlplatz, this tiny room hardly deserved to be called an apartment. Three strides of her long legs were enough to send her crashing into the opposite wall. There were two beds, a small corner table, a chair, and a chest of drawers. Planks of wood supported by cement blocks swayed under the weight of books and papers. This would be home to Olga and Otto for some time.

Noticing his lover’s surprise at the modesty of the accommodations, Otto quipped, “This place is a real bargain—to begin with, we’ll save what we would have had to spend on an alarm clock.”

The trolley car began its route at 6:00 A.M., passing right below their window and making a noise loud enough to wake the dead. That first morning in Berlin, Olga learned that she had changed more than her address. At breakfast—a bottle of milk and a few crackers—Otto explained that his clandestine work for the Party demanded certain precautions that would involve both of them. He opened a leather briefcase and removed several sets of identity papers.

“From now on, you will have two identities, just as I do. My official documents are in the name Arthur Behrendt, traveling salesman born in Augsburg, September 28, 1898. And, as of yesterday, you are my wife, Frieda Wolf Behrendt, born September 27, 1903, in Erfurt. Here are your identity papers and a document certifying that we live at 11 Erhardtstrasse, in Leipzig. Be very careful and the best of luck, Mrs. Behrendt.”

There was more: Otto’s illegal work would probably keep him away for weeks, sometimes months, at a time. “Which means that although we’ll be living together, it will be a while before I’ll be able to marry you,” he said tenderly.

Olga’s reaction was brusque. “Well, I think you should know that I have no intention of getting married.”

It didn’t take long for Olga to leave behind the adolescent from Munich and to become a woman. She made rapid progress within the Communist Youth of Neukölln, and a few months after arriving in Berlin she became secretary for agitation and propaganda in the most important workers’ base of the German CP—Neukölln. By day, there were meetings, protests, and street activities. At night, interminable assemblies in the depths of the old building on Zieten Street that housed the Müller family beer hall. The same large room that hosted a stream of local workers for their quick sausage-potato-and-beer midday meal became, in the early evening, headquarters for the district’s Communist Youth. No password was required for entry. Since the majority of the group was still under the drinking age, Müller reacted mechanically whenever some new young face appeared at the battered marble bar. His eyes narrowing between an enormous mustache and a rapidly receding hairline, he would simply say, “The Youth? Down that hallway, as far as you can go.”

Before coming to Berlin, Olga had heard many stories about the beer hall and its owners—Wilhelm Müller, his wife, and daughter. She knew the very corner in which Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht—two outstanding leaders of the German CP assassinated in 1919—had hatched their political schemes. Whenever the Müller family finances took a turn for the worse, the news would spread through Neukölln and beyond; the other beer houses in the area would stand empty as business increased dramatically at the Müllers’ for several weeks, until the family was back on its feet again. And twice a week, from 8:30 to 11.30 P. M., the back room that usually hosted political assemblies and clandestine meetings was transformed into a classroom. Every other Tuesday, Olga taught the rudiments of Marxist theory to a group of her comrades. Somehow they managed to juggle four or five different activities in the room simultaneously. There were times when Olga had to be gruff and request that someone come back another time to run off pamphlets on the mimeograph machine set up in one corner.

Work was relentless: pamphleting the Görlitzer railway station, demonstrations of support for strikes at neighborhood factories, protests against the imposition of extra working hours. And all of it had to fit in around the eight-to-six job that brought in the few marks she and Otto needed to live on. The Party had arranged for Olga to work as a typist for the Soviet Trade Bureau, and though the work was tedious compared with her activities with the Youth, she was proud of working “side by side with the revolutionaries.” While she knew it was probably just a fantasy, Olga saw “a Bolshevik of steel” in every one of those placid bureaucrats in jacket and tie.

Time for all these feverish activities had to be stolen from somewhere, and occasionally the couple’s love life seemed to suffer. The few hours a week they managed to be together—usually late at night—were usually spent working. After much insistence, Olga had finally convinced Otto that she should be his secretary, not only so that she would have more time with him, but also for the political apprenticeship it offered. It was she, then, who typed the voluminous theoretical texts he either dictated or left on the bed in handwritten form. And it was through this work that she began to understand more completely the approaching struggle in Germany, revolutionary developments in other countries, and of course the internal structure of the German Communist Party.

The mutual love and admiration of Olga and Otto did not diminish; on the contrary, it was growing stronger. At the same time, the political activity and the passion for militancy they also shared reduced to minutes the time they could spend as lovers. When they argued, it was not over political differences but over something that irritated Olga more and more: the jealousy Otto felt toward the young men in the Communist Youth. Justifiable jealousy, any one of her sixty comrades in Agitation and Propaganda might say, for Olga was becoming more attractive. Even her gangly walk gave her a certain special charm. And the one characteristic that really kindled their interest was her independence. Olga was her own boss and did only what she believed to be important, both in politics and in her personal life.

Fortunately, this independence didn’t prevent her from learning a great deal from Otto, and he taught her more than the theories of Marx, Lenin, Engels, and Karl Liebknecht. Advice that, coming from a woman friend, would have met with profanity, sounded different from Otto’s mouth. It wasn’t just the experienced Communist in him speaking. In patient, homeopathic doses, Otto convinced her that a militant need not be unkempt and poorly dressed—the few bottles of cologne and perfume on the couple’s small, improvised dressing table beside the sink belonged to him. As a result of their long, late-night talks in bed, Olga grew more tolerant of non-Communists and, more important, began little by little to give up her moral prejudices against comrades who smoked, drank, or spent their scant free time dancing on Saturday nights. As time went on, she herself began to feel attracted to the group’s various entertainments.

There was one notion, however, that even Otto was unable to shake loose, and that was her horror of formal, legally sanctioned marriage. Olga associated the idea of marriage with what she considered the worst of bourgeois deformities—the economic dependence of women, obligatory love, forced intimacy. When people asked why she and Otto—apparently very happy living together— didn’t get married, Olga had a ready answer. “That’s exactly why we won’t marry—because we’re happy, because we love each other. I will never allow myself to become another person’s property.”

But this way of looking at male-female relations didn’t presuppose other sorts of liberal ideas; Olga was very upset whenever she heard a girlfriend boast about how many men she’d gone to bed with. At such moments, an intolerant, almost puritanical Olga emerged. “You should know that giving in to your instincts is tantamount to contributing to the bourgeois brothel. And that’s not just me talking; it’s Lenin.”

Who could argue with Lenin? If a member of the group was guilty of behavior Olga considered “immoral,” she didn’t hesitate to bring up the problem for discussion with the leadership—and all this in the progressive Berlin of the twenties.

This rigid side of Olga didn’t discourage the young men of Neukölln from falling in love with her. A girl named Ruth, for example, insisted that her boyfriend, Martin Weiser, a young apprentice jeweler, should quit the Marxist study group taught by Olga in a Berlin suburb.

Kurt Seibt, another boy from the same group, who worked as a typesetter and had managed to join the printers’ union, also fell under her spell. Olga had inspired him to join the Communist Youth, and he became a sort of teaching assistant to her. Kurt believed, along with Olga, that the natural step following theoretical course work and the recruitment of young people in working class neighborhoods was the clandestine militarization of the group. Under Olgas guidance, he took on the task of organizing young militia in each city block of Kreuzberg, a neighborhood near Neu-kolln. Despite its importance, this new post had the distinct disadvantage of separating him from his attractive mentor.

The first time he saw Olga after assuming h...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Dedication1

- Berlin

- Buenos Aires

- 1. Inside the Red Fort

- 2. In Jail

- 3. Enter the Knight of Hope

- 4. Honeymoon in New York

- 5. Destination Rio

- 6. The Conspiracy Begins

- 7. Revolution in the Streets

- 8. A Spy Among the Communists

- 9. Mr Xanthaky Appears

- 10. “Miranda” and Ghioldi Talk

- 11. In Pursuit of Olga

- 12. The Police “Suicide” Barron

- 13. The Brazilian Ambassador and the Gestapo

- 14. A “ Noxious” Foreigner

- 15. Rebellion in “Red Square”

- 16. In the Cellars of the Gestapo

- 17. Dona Leocádia Takes On the Gestapo

- 18. With Sabo in the Nazi Fortress

- 19. Slavery at Ravensbrück

- 20. The Final Journey

- São Paulo, July 1945

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Sources

- Index

- Foot Notes