eBook - ePub

Groovy Science

Knowledge, Innovation, and American Counterculture

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Groovy Science

Knowledge, Innovation, and American Counterculture

About this book

In his 1969 book The Making of a Counterculture, Theodore Roszak described the youth of the late 1960s as fleeing science "as if from a place inhabited by plague," and even seeking "subversion of the scientific worldview" itself. Roszak's view has come to be our own: when we think of the youth movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, we think of a movement that was explicitly anti-scientific in its embrace of alternative spiritualities and communal living.

Such a view is far too simple, ignoring the diverse ways in which the era's countercultures expressed enthusiasm for and involved themselves in science—of a certain type. Rejecting hulking, militarized technical projects like Cold War missiles and mainframes, Boomers and hippies sought a science that was both small-scale and big-picture, as exemplified by the annual workshops on quantum physics at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, or Timothy Leary's championing of space exploration as the ultimate "high." Groovy Science explores the experimentation and eclecticism that marked countercultural science and technology during one of the most colorful periods of American history.

Such a view is far too simple, ignoring the diverse ways in which the era's countercultures expressed enthusiasm for and involved themselves in science—of a certain type. Rejecting hulking, militarized technical projects like Cold War missiles and mainframes, Boomers and hippies sought a science that was both small-scale and big-picture, as exemplified by the annual workshops on quantum physics at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, or Timothy Leary's championing of space exploration as the ultimate "high." Groovy Science explores the experimentation and eclecticism that marked countercultural science and technology during one of the most colorful periods of American history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Groovy Science by David Kaiser, W. Patrick McCray, David Kaiser,W. Patrick McCray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226372914, 9780226372884eBook ISBN

9780226373072Part One: Conversion

1

Adult Swim: How John C. Lilly Got Groovy (and Took the Dolphin with Him), 1958–1968

D. Graham Burnett

What did it mean to be “groovy” circa 1970? It meant knowing how to hang, how to float, how to be at one with others, with animals, with the universe itself. I believe we can treat the following text as paradigmatic of the project as a whole:

I suspect that whales and dolphins quite naturally go in the directions we call spiritual, in that they get into meditative states quite simply and easily. If you go into the sea yourself, with a snorkel and face mask and warm water, you can find that dimension in yourself quite easily. Free floating is entrancing. . . . Now if you combine snorkeling and scuba with a spiritual trip with the right people, you could make the transition to understanding the dolphins and whales very rapidly.1

Spiritual cetaceans? Trippy, collective, free-floating ethology of the odontocetes? Where are we?

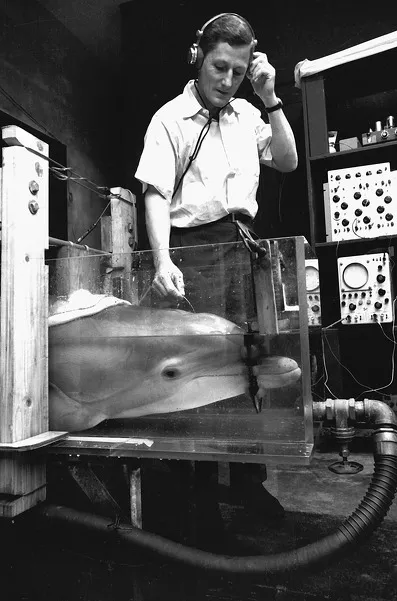

The short answer is that we are located firmly in the head—the very heady head—of one of the most important, and one of the strangest, scientists of the 1960s: John C. Lilly, the man whose work with brains and behaviors of dolphins had lasting implications for cultural understanding of human beings’ nearest aquatic kin (fig. 1.1). A pioneering neurophysiologist, a troubled military psychologist, an apostate cetologist and animal fantasist, ultimately a Pied Piper of whale hugging and cosmonaut of heightened consciousness—John C. Lilly traced a fascinating trajectory across the postwar period. Retracing a parabolic portion of his path (he rose and he fell) will allow us, I think, to catch several striking views of what we may indeed want to call “groovy science.”

Figure 1.1 John C. Lilly at work in the lab. Reprinted by permission of the Flip Schulke Archives. © Flip Schulke.

Lilly and the Cetacean Brain

Born in 1915, Lilly, from a well-to-do family in Saint Paul, Minnesota, took a bachelor of science degree from the California Institute of Technology in 1938 and studied at Dartmouth Medical School for two years before moving to the University of Pennsylvania, where he completed his MD in 1942 and remained on the faculty. There, under the influence of Britton Chance and Detlev Bronk, Lilly pursued research in biophysics, including applied investigations into real-time physiological monitoring—work linked to wartime service in military aviation, where techniques for assaying the respiration of airmen were needed.2 Lilly had contact through his family with the neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield in the later 1940s and developed an interest in neuroanatomy and the electrophysiology of the brain. By 1953 he had been appointed to the neurophysiology laboratory of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), where he worked under Wade Marshall as part of a joint research program with the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness.

By the mid-1950s Lilly’s lab in Bethesda, Maryland, was performing in vivo electrical stimulation of the brains of macaques—work aimed at cortical mapping by means of correlating point applications of currents at varying thresholds with specific behaviors and reactions in subject animals.3 Reporting on some of these investigations at a conference on the reticular formation of the brain, held in Detroit in 1957, Lilly would explain,

The neurophysiologist has been given a powerful investigative tool: the whole animal can be trained to give behavioral signs of what goes on inside. . . . We are in the position of being able to guess with less margin of error what a man might feel and experience if he were stimulated in these regions.4

This was, in many ways, unpleasant business, Lilly acknowledged, pointing out that he had “spent a very large fraction of my working time for the last eight years with unanaesthetized monkeys with implanted electrodes.” In addressing the nebulous region where neurology, psychology, and animal behavior overlapped, Lilly permitted himself some observations on the affective universe of his scientific subjects:

When an intact monkey grimaces, shrieks, and obviously tries to escape, one knows it is fearful or in pain or both. When one lives day in and day out with one of these monkeys, hurting it and feeding it and caring for it, its experience of pain or fear is so obvious that it is hardly worth mentioning.5

It would not be the last time that Lilly would reflect on the inner lives of his experimental animals with considerable confidence. But his experimental animal was about to change. Like a number of American psychology researchers in the mid-1950s—including the echolocation researcher Winthrop Kellogg—Lilly was in the process of leaving monkeys behind for the bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus.

His first brush with the study of cetaceans came in 1949 when, during a visit to a neurosurgeon friend on Cape Cod, Lilly learned that a recent storm had beached a whale on the coast of southern Maine. A plan took shape for an impromptu expedition north, with a view toward collecting a novel brain.6 As it happened, Lilly was acquainted from his days at the University of Pennsylvania with the Swedish-Norwegian physiologist and oceanographer Per F. “Pete” Scholander, who had also worked with Detlev Bronk in aviation physiology during World War II and had then moved to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.7 Scholander—something of a daredevil, and fascinated by the physiology of extreme environments—had published research on dive physiology and decompression, and while still living in Scandinavia he had conducted a number of pioneering studies on the deep-diving capabilities of marine mammals, particularly whales.8 Lilly looked up Scholander and recruited him for the trip, and the three men suited up for a drive to Maine. Shortly after reaching the carcass (a large pilot whale), exposing the skull, and beginning to chip away toward the brain, they were joined by two other researchers who had independently made the drive up from Woods Hole: William Schevill and his wife and collaborator, Barbara Lawrence. They were, reportedly, somewhat miffed to discover that they had been beaten to the punch and were particularly concerned that the hacksaw dissection might have damaged the airways of the upper head, which they had come to examine. In the end, however, the cadaver would be theirs, since Lilly and his partners found that the brain had largely been dissolved through autolysis; the smell alone overpowered them.

Though he headed home with little to show for the trip, Lilly had brushed the shores of cetology, and his curiosity did not dissipate. At a meeting of the International Physiological Congress four years later, in 1953, Lilly and Scholander again crossed paths, and Scholander suggested that Lilly get in touch with a leading expert on captive dolphins, Forrest G. Wood, who at that time handled the animals at Marine Studios. Lilly did, and as a result, he was one of eight investigators to participate in what came to be known informally as the “Johns Hopkins expedition” in the autumn of 1955. Like prewar projects, the expedition featured a mixed crew of physiologists and medical men gearing up to vivisect some bottlenose dolphins, only this time it would be in the carnival environs of a Florida ocean theme park rather than a remote fishing village on a barrier island.9

In preparation for this 1955 trip, Lilly spent the summer in correspondence not only with Wood (securing access to a set of dolphins for experimental work) but also with Schevill at Woods Hole (concerning the anatomy of the airways of the common dolphin)10 and with Scholander (concerning restraint techniques and the respiratory characteristics of the odontocetes).11 Using this information, Lilly worked up a dolphin respirator that would, it was hoped, permit the surgeons and neuroscientists of the party to expose the brain of an anesthetized animal in order to begin the work of cortical mapping by neurophysiological techniques. It appears that no one in Europe or the United States up to this point had attempted a “surgical” intervention on a dolphin or porpoise.

The Johns Hopkins expedition of 1955 was at best a qualified success. Lilly and the other investigators were unsuccessful with their anesthetics and their respirator, and in the end they euthanized, without dexterity, five dolphins, apparently alienating a number of the Marine Studios personnel in the process.12 But if the 1955 investigations were not a triumph, they did deepen Lilly’s continuing interest in the cetacean brain.13 Having heard a set of Wood’s recordings of bottlenose dolphins at Marine Studios, Lilly was much struck—as were a considerable number of others at this time—by the range and apparent complexity of dolphin phonation. In October 1957 and again in 1958—after a visit with Schevill and Lawrence in Massachusetts, where they were conducting work on the auditory range and echolocatory capabilities of a bottlenose dolphin in a facility near Woods Hole—Lilly returned to Marine Studios. This time he was equipped to undertake investigations of the dolphin brain and behavior using techniques like those he had deployed and refined with macaques at NIMH: namely, percutaneous electrodes, driven by stereotaxis, that could probe the brain tissue of an unanesthetized, living animal.14 Over the two visits, three more animals were sacrificed, and Lilly experienced a kind of scientific epiphany that would shape his scientific life, even as its reverberations eventually unmade his scientific reputation.15

Compressing a complicated encounter that took place over several days—and which continued to draw Lilly’s reflections and reconstructions for years—is not easy, but we can summarize Lilly’s sense of his findings this way: First, Lilly persuaded himself that, in comparison to his experience with monkeys, the dolphins appeared to learn very rapidly how to press a switch to stimulate a “positive” region in their brains (and to turn off stimulation to a region causing pain).16 Second, he claimed to have been much struck by the sense that an injured experimental subject, when returned to the tank with other dolphins, “called” to them and received their ministrations, suggesting an intraspecies “language.”17 Third, on reviewing the tapes made of these investigations, Lilly grew increasingly certain that his experimental subjects had been parroting his speech and other human sounds in the laboratory. These three elements—intelligence, an intraspecies language, and (perhaps most significantly) what he took to be fleeting glimpses of an attempt at interspecies communication—left Lilly with a feeling that he was on the cusp of something vast. Reflecting on the work of 1955, 1957, and 1958 in his Lasker Lecture in April 1962, Lilly tried to explain:

We began to have feelings which I believe are best described by the word “weirdness.” The feeling was that we were up against the edge of a vast uncharted region in which we were about to embark with a good deal of mistrust concerning the appropriateness of our own equipment. The feeling of weirdness came on us as the sounds of this small whale seemed more and more to be forming words in our own language.18

After hammering his way into hundreds of mammalian brains, Lilly suddenly heard a voice.

Odd as this breakthrough may seem, Lilly was not alone in his sense of the magnitude of what had happened in the Marine Studios laboratory in the late 1950s. One of Lilly’s medical friends who had been in attendance in October 1957, during work on dolphin number six, later mused to him in a letter, “I keep thinking of that first moment when the first, clearly purposeful switch-pressing response occurred. This is one of the extraordinary moments in science.”19 Loren Eiseley, the anthropologist who had become the provo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Conversion

- Part Two: Seeking

- Part Three: Personae

- Part Four: Legacies

- Contributors

- Index