- 484 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This "absorbing history of the Ordnance Survey"—the first complete map of the British Isles—"charts the many hurdles map-makers have had to overcome" (

The Guardian, UK).

Map of a Nation tells the story of the creation of the Ordnance Survey map, the first complete, accurate, affordable map of the British Isles. The Ordnance Survey is a much beloved British institution, and this is—amazingly—the first popular history to tell the story of the map and the men who dreamt and delivered it.

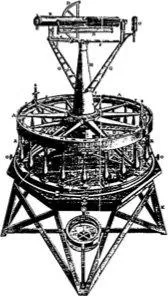

The Ordnance Survey's history is one of political revolutions, rebellions and regional unions that altered the shape and identity of the United Kingdom over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It's also a deliciously readable account of one of the great untold British adventure stories, featuring intrepid individuals lugging brass theodolites up mountains to make the country visible to itself for the first time.

Map of a Nation tells the story of the creation of the Ordnance Survey map, the first complete, accurate, affordable map of the British Isles. The Ordnance Survey is a much beloved British institution, and this is—amazingly—the first popular history to tell the story of the map and the men who dreamt and delivered it.

The Ordnance Survey's history is one of political revolutions, rebellions and regional unions that altered the shape and identity of the United Kingdom over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It's also a deliciously readable account of one of the great untold British adventure stories, featuring intrepid individuals lugging brass theodolites up mountains to make the country visible to itself for the first time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Map of a Nation by Rachel Hewitt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

‘A Magnificent Military Sketch’

I

ON 29 JUNE 1704, in a north-western suburb of Edinburgh, Mary Baird, the well-to-do wife of a successful merchant called Robert Watson, gave birth to her eleventh child: a son they called David. David Watson’s earliest years were spent in Muirhouse, which is now a sprawling housing estate to the north of Scotland’s capital, but was then a prosperous area populated by traders, where his father had recently purchased an enviable house with surrounding land. David was the baby of a large family, whose siblings ranged in age from two to fourteen, and around whom a host of affluent aunts and uncles clustered. But at the age of eight the young boy’s life underwent a dramatic upheaval: David’s father suddenly died. And in that same year his eldest sister Elizabeth, whose portrait shows her to have had kind but nervous eyes, a hesitant smile and luxuriant auburn hair, married into one of Scotland’s most influential families.

Elizabeth Watson’s suitor was a 27-year-old lawyer called Robert Dundas, heir to a dynasty whose command of the Scottish legal system in the eighteenth century has led it to be termed the ‘Dundas despotism’. His family played such significant roles in public life that their Victorian biographer concluded that ‘to describe, in full detail, the various transactions in which they took the leading part would be to write the history of Scotland during the greater part of the eighteenth century’. Robert Dundas himself was a star in the legal firmament. He had been made Solicitor General of Scotland at a precociously young age, and rapidly attained the positions of Lord Advocate, Dean of the Faculty of Advocates and Lord President of the Court of Session. His reputation was immense: he was described as ‘one of the ablest lawyers this country ever produced’.

Gruff, with a tendency to irritability, Dundas was hardly the smooth and urbane lawyer one might expect. Physically he was not prepossessing. A friend described him as ‘ill-looking, with a large nose and small ferret eyes, round shoulders’ and ‘a harsh croaking voice’ with a robust Lowland Scottish accent. He was a man of unpredictable extremes, whose temper was said to be characterised by ‘heat’ and ‘impetuosity’ but matched with ‘abundance of tact’. He drank prodigiously – a bill for wine at his mansion over a nine-month period came to the equivalent of £11,000 – but he was still able to conduct his work with clarity and precision, even after ‘honouring Bacchus for so many hours’, as the novelist Walter Scott put it. And despite this erratic character, Dundas was highly respected. It was said that within three sentences his listener was invariably swayed by such ‘a torrent of good sense and clear reasoning, that made one totally forget the first impression’. Taking into account his inheritance of the stunning and capacious estate of Arniston on the fertile banks of the river Esk in Midlothian, Robert Dundas was an entirely desirable prospect for Elizabeth Watson.

At the time of her marriage, Elizabeth had just lost her father, and it is possible that her mother was also deceased by this point, as she and her new husband became something of surrogate parents to her eight-year-old brother David. His contact with the Dundas family would change the course of David Watson’s life. It was an exciting time: the atmosphere of Lowland Scotland was alive with optimism in the early eighteenth century. In 1707, an Act of Union had officially united Scotland and England into ‘Great Britain’ and, in the emerging ‘Age of Enlightenment’, the intellectual climate of this young nation was buzzing with a new intensity. The Dundases had played central roles in the Union and they considered themselves to be standard-bearers of the Scottish Enlightenment. His intimacy with this influential family would open up an array of opportunities to the young David Watson.

THE ONSET OF an Age of Enlightenment in Britain was enormously helped by two events that had occurred in 1687 and 1688. The publication of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), and the ‘abdication’ of King James II of England, followed by the arrival of his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband William as joint monarchs, were events that were both widely considered to demonstrate the potential of human powers of reason. Newton’s Principia Mathematica revealed that, despite its semblance of arbitrariness and confusion, the cosmos was really a unified system. And the ‘Glorious Revolution’ that was marked by James II’s departure set a new precedent for the relationship between the government and the Crown, founded on the rational principles that Britons deserved ‘the right to choose our own governors, to cashier them for misconduct, and to frame a government for ourselves’. Following these momentous occurrences, the philosophers of the British Enlightenment emphasised that science, politics, geography, art and literature should be guided by reason above all else. They were confident that powers of rationality could uncover the truth about the world. One of the key aspirations of Enlightenment thinkers was the creation of a vibrant ‘public sphere’ in which every member of the populace would feel free to ‘Sapere aude!’ – to dare to think for themselves.

The Enlightenment had important consequences for maps and map-making in Britain. A new ideal was dangled before surveyors: that cartography could be a language of reason, capable of creating an accurate image of the natural world. Enlightenment thinkers invested maps with the hope that the repeated observation and measurement of the landscape would build up an archive of knowledge that approached to perfect truth. The French philosophes Diderot and d’Alembert saw maps as images of the ordered, rational mind, and they compared their own Encyclopédie to ‘a kind of world map’ whose articles functioned like ‘individual, highly detailed maps’. The natural philosopher Bernard de Fontenelle described the zeitgeist of the Age of Enlightenment as an ‘esprit géométrique’. The twentieth-century Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges has encapsulated the desire of thinkers in this period for ultimate ‘Exactitude in Science’ by likening it to the ultimately doomed objective to make ‘a Map of the Empire’ on the scale of one-to-one, whose ‘size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.’

Accuracy, or rather ‘the quantifying spirit’, thus became a new priority for map-makers in the eighteenth century, inspiring such dramatic advances in instruments and methods that, by the second half of the century, Britain was home to some of the most precise map-making and astronomical instruments in the world and the most diligent, rational surveyors. The emergence of relatively trustworthy maps had profound effects on the way they were used by the general populace. As we shall see later, the new maps assisted the process by which Britain’s component regions were integrated into a unified nation. Progress in cartography occurred in parallel with the improvement of the nation’s road networks, the innovations in coach design that made travel cheaper and less uncomfortable, and historical and cultural events that heralded a new dawn in the British tourist industry. Maps became hallmarks of an ‘enlightened’ mind and nation. And in 1720 a surveyor called George Mark issued a call to arms to the principal players of the Scottish Enlightenment, begging them to further the state of cartography: ‘’Tis truely strange why our Scotish [sic] Nobility and Gentry, who are so universally esteemed for their Learning, Curiosity and Affection for their Country, should suffer an Omission of this Nature … in what so much concerns the Honours of the Nation!’

DAVID WATSON GREW up in the early decades of the Scottish Enlightenment among a family who were enthusiastic sponsors of its values. In spite of a certain degree of anti-intellectual bluster on Robert Dundas’s part, and his reputation for never having been ‘known to read a book’, Arniston’s library was impressively stocked with travel-narratives, topographical writings, atlases, maps and expensive globes. A theoretical knowledge of surveying was considered integral to the education of an enlightened gentleman, who was expected to be able to commission and judge maps of his own estate. Arniston House accordingly boasted an inspiring collection of surveying instruments and a series of cartographic depictions of the large and varied surrounding estate. We can imagine that David Watson, and Elizabeth and Robert Dundas’s own children, looked on in fascination as well-known estate surveyors, and famous architects such as William Adam, laid measuring chains along the lengths of the youngsters’ favourite avenues of trees, translating the familiar Midlothian landscape into numbers, angles and lines on a map.

The Dundases’ enthusiasm for geography was such that they even attended the prestigious lectures on surveying that were delivered by the Edinburgh mathematician Colin Maclaurin. A child prodigy who was elected Professor of Mathematics at Aberdeen University at the age of nineteen, Maclaurin had so impressed Isaac Newton with his work that Newton had even offered to pay his salary. At Edinburgh, Maclaurin devised a rigorous course of mathematical education that emphasised the discipline’s practical applications, especially to map-making. The Scots Magazine described how, in his lectures, Maclaurin ‘begins with demonstrating the grounds of vulgar and decimal arithmetic; then proceeds to Euclid; and after … insists on surveying, fortification and other practical parts’. Maclaurin’s lecture-theatre was an intellectual hothouse that produced a brood of illustrious surveyors, architects and mathematical instrument-makers such as Alexander Bryce, Murdoch Mackenzie, Robert Adam and James Short. Sitting in Maclaurin’s audience, the Dundases, and perhaps Watson too, were among inspiring cartographical company.

As David Watson approached his mid teens, his sister and her husband applied themselves to furthering his career. Characteristically of younger relatives of the gentry, Watson expressed an interest in joining the Army. Robert Dundas used his influence to obtain a commission for his younger brother-in-law, and Watson duly spent much of his twenties and thirties on the Continent. He endured a ‘long banishment at Gib[raltar]’, where the British were building fortifications, and he enjoyed a martial ‘Scuffle’ during the War of the Polish Succession. But while Watson was fighting abroad, tragedy struck at Arniston. In November 1733 Elizabeth and Robert’s young son came home from the local school in Dalkeith with signs of sickness. The symptoms rapidly worsened and revealed themselves as smallpox, and the boy was dead within a week. The couple’s three other little children were infected and one by one between November 1733 and January 1734 they all died. By early December 1733 Elizabeth herself was ‘confind to her Chamber and pretty much to her bed’. When her two small daughters died at the beginning of the new year, their mother was too weak to be told. By 6 February 1734 this poor woman had finally succumbed.

Robert Dundas retreated to London to mourn ‘the best of mothers’ and ‘an incomparable wife’. But as one door closed for him, another was about to open. A couple of weeks before the arrival of the smallpox at Arniston, Dundas had paid a visit to a client in the Upper Ward of Lanarkshire, a region stretching south from the town of Carluke, about nineteen miles south-east of Glasgow. Sir William Gordon was the owner of two conjoined estates, Hallcraig and Milton, which extended west from Carluke along the dank northern edge of a small brook called Jock’s Gill, then reached up onto wide fertile plains, before dropping down into the lush crook of the river Clyde, where the road stopped for want of a bridge. Sir William was a canny operator, one of the very few to have made money from the South Sea Bubble – the stockmarket crash that had devastated Britain’s economy in 1720 – and he had been seeking legal advice from Dundas for over a decade. No doubt one of the chief attractions of Gordon’s case for his lawyer was his young daughter Ann: a spirited, flirtatious and enormously beautiful woman. Her portrait, painted by the famous Joseph Highmore and now hanging on a staircase in Arniston House, shows large dark eyes slanted in readiness to laugh, fashionably alabaster skin and teak-coloured hair from whose arrangements a few unruly curls escaped. Elizabeth Dundas, to whom writing did not come naturally, had not been able to accompany her husband to Lanarkshire on this occasion and she laboured over a formal apology to Ann, hoping to ‘have the happness [sic] to see’ the eighteen-year-old woman in Edinburgh soon.

Robert Dundas’s visit to Milton in October 1733 lasted only a few days. His carriage overturned on the bad roads that led out of Carluke on his way home, and he suffered what Elizabeth termed ‘a truble in his bake’ for many weeks. Upon returning to Arniston, Dundas too wrote to Ann. ‘I won’t omitt ane opportunity of writing to you however litle I may have to say,’ he assured her. He was positive that, ‘when I speak of affection[,] good oppinion and every good wish I am capable of, these will be no news to you’. Dundas designated Ann his ‘rival wife’, and he reflected ponderously that ‘this is quite new for a man and two wifes to be all one’. He signed off by exhorting her to ‘believe me Dear Anne’ that he was ‘with the greatest esteem and pleasure, as much yours as I can be … my Dear Girl’.

In the wake of Elizabeth’s death only a few months later, Ann Gordon wrote back to Robert Dundas. She sympathised with ‘the Loss You have … Made’ but she firmly reminded him that ‘You once gave me Reason to Pretend some Tittle to Your Heart’. With a mixture of sincerity and flirtatiousness, Ann openly informed this man, who was almost thirty years her senior, that ‘I Intend to Pursue You with so Much Friendship & Contempt[,] Love and Indifference as Must Convince You’. He was easily convinced and the ‘rival wife’ soon became his lawful spouse. Ann and Robert’s wedding took place four months after Elizabeth’s death. There were few guests. In the circumstances of the recent devastation of Dundas’s first family, a discreet wedding seemed appropriate. Dundas d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- PROLOGUE : Lost and Found

- CHAPTER ONE : ‘A Magnificent Military Sketch’

- CHAPTER TWO : ‘The Propriety of Making a General Military Map of England’

- CHAPTER THREE : The French Connection

- CHAPTER FOUR : The Aristocrat and the Revolution

- CHAPTER FIVE : Theodolites and Triangles

- CHAPTER SIX : The First Map

- CHAPTER SEVEN : ‘A Wild and Most Arduous Service’

- CHAPTER EIGHT : Mapping the Imagination

- CHAPTER NINE : The French Disconnection

- CHAPTER TEN : ‘Ensign of Empire’

- CHAPTER ELEVEN : ‘All the Rhymes and Rags of History’

- CHAPTER TWELVE : ‘A Great National Survey’

- EPILOGUE : Maps of Freedom

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Acknowledgements

- Illustration Credits

- Index

- A, B, C

- D, E, F

- G, H, I

- J, K, L

- M, N, O

- P, Q, R

- S, T, U

- V, W, X

- Y, Z

- Plates

- Copyright