- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

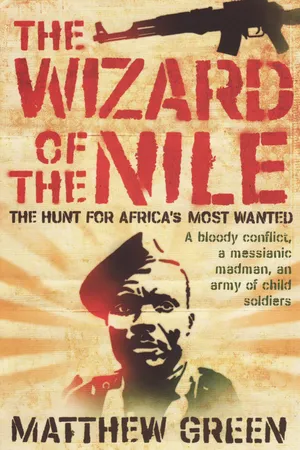

About this book

A foreign correspondent's chronicle of the Ugandan warlord and his Lord's Resistance Army of abducted child soldiers: "a readable and compelling account" (

Independent, UK).

Somewhere in the jungles of Uganda, there hides a fugitive rebel leader: he is said to take his orders directly from the spirit world and, together with his ragged army of brutalized child soldiers, he has left a bloody trail of devastation across his country. Joseph Kony is now an internationally wanted criminal, and yet nobody really knows who he is or what he is fighting for.

To get the truth behind the rumors and myths, Matthew Green ventures into the war zone, meeting the victims, the peacemakers and the regional powerbrokers as he tracks down the man himself. The Wizard of the Nile is the first book to peel back the layers of mysticism and murky politics surrounding Kony, to shine a searching light onto this forgotten conflict, and to tell the gripping human story behind an inhumane war and a humanitarian crisis.

Winner of the Jerwood Award

Long-listed for the Orwell Prize

Somewhere in the jungles of Uganda, there hides a fugitive rebel leader: he is said to take his orders directly from the spirit world and, together with his ragged army of brutalized child soldiers, he has left a bloody trail of devastation across his country. Joseph Kony is now an internationally wanted criminal, and yet nobody really knows who he is or what he is fighting for.

To get the truth behind the rumors and myths, Matthew Green ventures into the war zone, meeting the victims, the peacemakers and the regional powerbrokers as he tracks down the man himself. The Wizard of the Nile is the first book to peel back the layers of mysticism and murky politics surrounding Kony, to shine a searching light onto this forgotten conflict, and to tell the gripping human story behind an inhumane war and a humanitarian crisis.

Winner of the Jerwood Award

Long-listed for the Orwell Prize

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wizard of the Nile by Matthew Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

A PROPHET FROM GOD

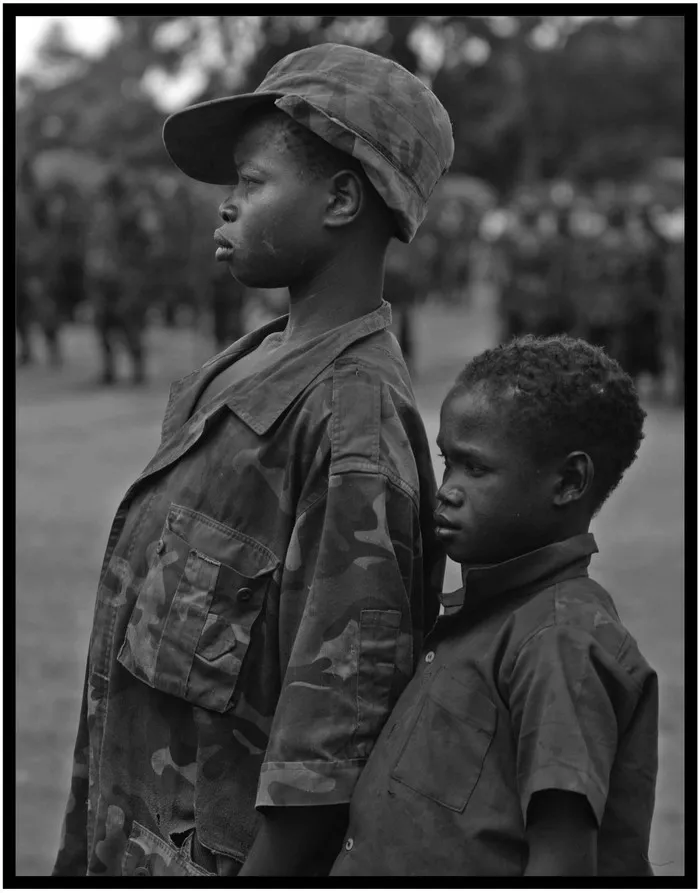

Former LRA child soldiers on parade

The bus hurtled north, glittering bush rushing past on either side of the road. ‘Sexual Healing’ by Marvin Gaye blasted from the tinny speakers, alternating with gospel tracks. Passengers dozed or read the back page of the New Vision for the football reports. Nobody talked much. Soon the bus would reach the White Nile, and in a few more minutes we would cross into northern Uganda, the home of Joseph Kony.

The newspapers seemed to hold only a handful of pictures of him. One showed a man in his early thirties scowling from beneath a mop of dreadlocks. In another he sported a T-shirt with the slogan ‘Born to be Wild’, a gormless expression stamped on his face. The constant repetition of these same images had a curious effect – it was as if he never aged.

The news reports summed up Kony in crisp paragraphs: ‘A self-proclaimed prophet who claims to take orders from a Holy Spirit, Kony wants to rule Uganda according to the Biblical Ten Commandments. His Lord’s Resistance Army rebels have abducted thousands of children for use as soldiers, porters and sex slaves. They are reviled for cutting off their victims’ ears and padlocking their lips.’

I knew the paragraphs by heart, having spent the past few years writing them. I had been working as a journalist for Reuters news agency, based across the border in the Kenyan capital Nairobi. We handled stories from volcanic eruptions in Congo to coup attempts in Burundi and starvation in Sudan. Kony’s war stood out for the simple reason that it seemed to make no sense at all.

From our crow’s nest in Nairobi, the conflict looked like a classic tale of pointless savagery. The rebels had massacred villagers, mutilated hundreds of people and abducted thousands of children – all for the sake of one man’s ambition to rule according to his warped reading of the Bible. It was hard to credit, but the rebellion had turned into one of Africa’s longest civil wars. After twenty years, the sheer lunacy of the Kony story was so much a part of the wallpaper that I did not think to question it.

Then one day a magazine called The Referendum found its way into the newsroom. It was published irregularly by a group of journalists from southern Sudan, a region that lies across the border from northern Uganda. Kony had sheltered there for years. Spelling errors sometimes crept into the layout – in one issue, ‘messengers’ of the truth became ‘massagers’. But the latest edition claimed to have won a remarkable scoop – the first ever interview with Kony. The anonymous author said the rebel leader wanted to talk to Uganda’s president through the spirits, fearing telephones would be used to kill him.

Many people dismissed the article as a hoax, but I couldn’t stop thinking about it. If somebody had interviewed Kony, then it might just be possible to repeat the feat. Assuming he was not completely unhinged, he should be able to shed some light on the madness in his homeland. I asked my editors at Reuters for some time off work and made a plan.

I would begin my journey in a town called Gulu. I had the phone number of a Spanish missionary there named Father Carlos Rodríguez, who was one of the few foreigners to have met the rebels. From Gulu I would travel through Kony’s stamping grounds in northern Uganda and southern Sudan, loosely following the course of the White Nile. Along the way I would find out as much as possible about Kony and his war. My question was simple: how could one maniac leading an army of abducted children hold half a country hostage for twenty years?

In the comfort of Nairobi, putting the question to Kony himself had seemed like a fantastic idea. As the coach rushed towards the river, I was not so sure. Things had changed since The Referendum published its story. Rumour had it that the rebels had circulated a handwritten note in Gulu in which they threatened to kill any foreigners they found. A British man who had gone to help rafters in trouble on the White Nile had been murdered in the Murchison Falls National Park a couple of months before, and two de-miners had been shot dead in an ambush across the border in southern Sudan.

Some thought Kony wanted revenge. The new International Criminal Court in The Hague had recently issued its first arrest warrants. They named Kony and four of his commanders, accusing them of war crimes from massacring civilians to sexual enslavement. Kony himself faced thirty-three counts. He might be rumoured to dress as a woman, but just then he was one of the world’s most wanted men.

His followers seemed to regard him as something close to a messiah. I had saved a recording of his deputy commander, a man named Vincent Otti, on my iPod. Just before my visit he had called into a radio show in Kampala from a secret location.

‘What type of man is Mr Joseph Kony?’ the presenter asked.

Otti’s gravely voice sounded as though it was coming from far away.

‘Joseph Kony is a prophet.’

‘Sent by God?’ asked the presenter.

‘He’s really a prophet, I’m telling you. He is and you will even come to agree that he’s a prophet.’

The recording caught the sound of the studio guests sniggering.

A Canadian journalist on the panel asked if Otti would put Kony himself on the line. For a few tantalizing seconds it seemed as though he might even speak, but then Otti said his boss would talk ‘next time’. The recording ended.

Kampala had been a great place to spend a few weeks preparing for my trip. Nightclubs like Ange Noir and Club Silk stayed open until dawn, and there were plenty of cafés offering wireless internet to hang around in during the day. When the time came for me to leave, I had boarded our coach, misnamed the Luxury Explorer, and then waited for an hour while it filled up with passengers.

The bus nudged through chaotic streets in the older part of town, before breaking out into fields of matooke trees bearing cascades of spidery fruit. Farms soon gave way to wilderness as we sped further north, the endless green vista strangely sleep-inducing. Kony’s fighters had once lined up the bodies of their victims along this road as a warning, but now all I could see were columns of smoke as farmers burned distant fields.

The bus slowed and a smell of roasted meat drifted through the windows. Men and women rushed forward from a line of roadside shacks, thrusting skewers of diced beef at the passengers, dangling flapping chickens by their claws.

A pair of soldiers sat in the shade, manning a roadblock made out of a tree trunk. One of them climbed aboard the bus, shooting glances at the passengers before getting out and hauling the log aside. We rolled towards the bridge.

The land seemed to crack in half, a surge of white water foaming over rocks at the bottom of a gorge. A clean smell filled the coach, and the air was suddenly cool. From the speakers a woman sounding very much like Dolly Parton sang a love song, her voice struggling against the roar of the rapids. We passed another soldier who stared down at the torrent with a rifle slung across his back. A moment later the bus rounded a bend and the river vanished. We had crossed the Karuma Falls, the frontier between the peaceful south of Uganda, and the land of the Lord’s Resistance Army. A yellow sign by the roadside said ‘Safe journey’.

The sun was sinking by the time the bus reached Gulu, and I was keen to find a place to stay. A friend in Kampala had recommended the Franklin Guest House. It lay just around the corner from the coach park and only charged the equivalent of a few dollars a night. I set off.

Bicycles whirred through the streets, some with women sitting side-saddle on cushions on the back, heels rushing over the tarmac. A white four-by-four cruised past with the letters UN emblazoned on the side, its radio mast quivering. On the corner, a couple of women clattered out letters on typewriters, marking carriage returns with a satisfying ‘ping’. I found my way to the Franklin and took a small room facing onto a courtyard at the back.

As the light faded and the bicycle traffic thinned, Gulu looked much like any other farming town in East Africa. It had hardly changed since my first visit a few years before. I had stayed less than a week, filing a slew of stories for Reuters, but the images were hard to shake.

I remembered sitting at a table outside the Pearl Afrique Hotel, drinking tea, when a man approached me with a photograph. The snap was a little over-exposed, but I could clearly make out a clay pot propped up on stones over a fire. What appeared to be a human leg poked out from the top. Bodies lay strewn on the ground, missing limbs. The man scurried away before I could find out what had happened.

Later I met a boy called Geoffrey. The rebels had chopped off his ears, lips and fingers, and put a letter in his pocket warning the same would happen to anyone who thought about joining the government army. He was left with just enough purchase to clutch a bottle of Fanta between his stumps. He put it down and shook my hand with his leathery paws. Geoffrey said he had forgiven the people who had done this to him – hate would not bring back his fingers. But it was his last sentence that stuck in my mind. ‘I need shoes,’ he told me. He had hurt his toe playing football in bare feet.

It was almost obligatory for journalists to visit one of the centres set up to receive children who had escaped after being kidnapped by the rebels. I met a boy called Anthony who had managed to slip away during an attack by the army. Staring straight ahead, he recalled how he had been forced to participate in clubbing five people to death during his eleven days in captivity, a technique used by Kony’s men to create a perverse sense of loyalty by bloodying the hands of their new ‘recruits’. He wore a Star Wars T-shirt with an image from the film Phantom Menace.

Reports issued periodically by human rights organizations provided endless stories of atrocities committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army – usually referred to by their initials ‘LRA’. I flicked open a Human Rights Watch report I had found kicking around the newsroom, selecting a random example. On 24 February 2005, a year before my visit, the rebels had abducted a group of women who were on their way to fetch water. According to witnesses, one of the women had a baby who was crying. The five rebels told her they would kill it.

‘After some minutes the woman threw the baby down and ran. The rebels grabbed the woman and beat her to death with a gun. When the woman was killed one rebel got a stick and pierced through the child’s head. The child was two weeks old.’

From reading the reports, and making brief visits to Gulu, it seemed impossible to grasp what was happening. Even after all these years, nobody I spoke to seemed to know why Kony was fighting. They would shrug and say things like ‘That man is complicated.’ It was like stepping into a horror film in which everything seemed normal on the surface, but where people were living under the shadow of an unseen monster they preferred not to discuss.

With my visits lasting only a few days, the people I met became little more than caricatures acting out a story I thought I knew was true. Rebels in an obscure corner of Africa were doing awful things to innocent civilians; victims needed more help from well-meaning outsiders; children were suffering the most. This time, I wanted to go deeper.

Before this trip, I had scoured the library at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London for anything I could find on northern Uganda’s Acholi – a group of about 1.2 million people. Though communities in the neighbouring Lango, Teso and Adjumani areas also suffered, it was the Acholi who seemed to hold the key. Kony was an Acholi and so were most of his rebels, and indeed most of the people caught up in the war.

I read tales of witches luring snakes into huts with dishes of beer to extract their poison, of rainmakers summoning storms and warriors stitching the severed heads of their enemies into royal drums. And I stumbled upon a book chronicling an expedition that seemed remarkably close to my own journey.

A British reverend named Albert B. Lloyd, author of a book on Congo called In Dwarf Land and Cannibal Country, had penned a later work with a less intriguing title that nevertheless grabbed me immediately. First published in 1906, exactly a century before my visit, the book was called Uganda to Khartoum – Life and Adventure on the Upper Nile.

The black and white photos were surprisingly sharp, showing a pair of young men in warpaint with the caption ‘Acholi Swells’, and a party of hunters standing knee-deep in a river looking at four hippos that Lloyd had kindly shot for them. The back flap still contained an advertisement informing readers that ‘Wright’s Coal Tar Soap’ was to be known as ‘Soldier’s Soap’. It included an extract from a letter dated 8 April 1916, from a soldier serving in the trenches in France to a worried parent: ‘Don’t send any vermin powder thanks; I use Wright’s coal tar soap, that’s as effective and much more pleasant.’

Lloyd encountered a chief named Awich who smoked a pipe and wore scraps of soldiers’ uniform, women who leapt off roofs with grief at funerals, and a leader with fifty wives and sixty children, though I doubt he would have recognized the land I visited a century later.

Almost two million people had been forced off their land into squalid ‘protected camps’ as part of the government’s counterinsurgency strategy. At Reuters, we faithfully described northern Uganda as one of the world’s ‘worst humanitarian crises’, largely forgotten by the outside world. Like Kony, it was just too obscure.

Gulu came to life early. Children in pink shirts walked past clutching exercise books, while a barefoot boy wandered up to the Franklin offering twists of peanuts. Somewhere I could hear a brass band tuning up. I was due to meet Father Carlos at the St Monica’s tailoring school for young women who had escaped Kony’s ranks, but I still had time to buy a newspaper.

The New Vision was full of stories about the elections which were due to take place in a couple of weeks. President Museveni had already been in power for twenty years. He had declared at the time of the last elections in 2001 that he...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Maps

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- Table of Contents

- Epigraph

- PROLOGUE: A FUNERAL

- Chapter One : A PROPHET FROM GOD

- Chapter Two : WE ARE THE ANGELS

- Chapter Three : DAUGHTER OF THE MOON

- Chapter Four : FEEDING THE PRISONERS

- Chapter Five : A THUG WITH A CROSS

- Chapter Six : ‘GOD IS A KILLER’

- Chapter Seven : ‘SHOCK THE WORLD’

- Chapter Eight : THE MOST DESOLATE SPOT ON EARTH

- Chapter Nine : MR DUSTY

- Chapter Ten : THE SECOND COMING

- Chapter Eleven : ‘WE WANT TO SEE YOUR CHAIRMAN’

- Chapter Twelve : A GIRL CALLED PEACE

- Chapter Thirteen : A STRANGE KIND OF WIZARD

- Chapter Fourteen : ‘I AM REFORMED’

- EPILOGUE

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- A NOTE TO THE READER

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Advertisement

- About the Author

- Copyright