![]()

1

Altered Course

To walk the streets of Smyrna was to exploit all of the senses. The ears were assaulted with the whine of kemence violins, the shouts of children at play, the horns of impatient motorists, the Muezzin calling the faithful to prayer. The pungent odor of roasting lamb filled every breath, while dust from the narrow streets parched the throat. Strings of drying laundry waved from buildings like semaphore signals and colorful rugs brightened even the darkest thresholds. This was Turkey—a paradise of sun, sea, mountains, and lakes; a land of historic treasures and mystery.

On this day, Friday, December 8, 1933, a crisp winter sun reigned high in the sky, with temperatures pleasant in the mid-fifties. The weather reminded twenty-seven-year-old Virginia Hall of an early fall day in her native state of Maryland. And in Turkey, as it would have been in Maryland, it was a perfect day for a hunt. While most of Virginia’s days were consumed with clerking duties at the American Consulate in the coastal city of Smyrna, her spare time allowed her to pursue her passions, which included horseback riding and hunting.

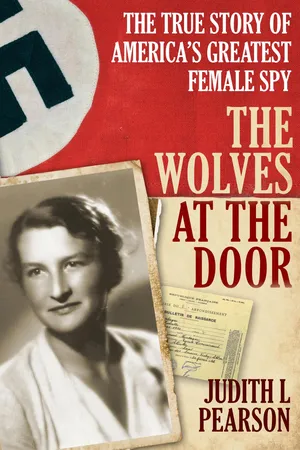

Virginia had learned to handle firearms at an early age from her father and had spent many summer days hunting birds and small animals on the family’s 110-acre Maryland estate, Box Horn Farm. Never one to shy away from the slightest challenge, Virginia grew up a tomboy in every sense of the word. At five foot seven, she was taller than most of the other girls in her class at school. She was slender and pretty, with high cheekbones and a determined chin highlighting her face. Her soft, brown hair fell in natural waves, and her eyes, clear, bright and deep brown, never caused anyone she encountered to think twice about where she stood on an issue.

W. Perry George, the American consul in Smyrna and Virginia’s boss, considered the consulate lucky to have her on staff. In his 1933 annual efficiency report, he described Virginia as “absolutely reliable as to honesty and truthfulness” and having a “good sense of responsibility.” And while he said her typing was not always accurate and she was somewhat absentminded, he reported that she was “very conscientious and helpful with a charming personality.” For her part, Virginia considered her position at the consulate in Smyrna one step closer to her dream, that of becoming a Foreign Service officer.

The city of Smyrna rendered many of the facets that had always been important in Virginia’s life. She was an avid reader. Smyrna was the birthplace of Homer, the father of dramatic literature. She greatly appreciated nature, and the city’s mild climate made flora and fauna plentiful. The constant, refreshing sea breezes tempered the summer sun’s heat and kept the winters mild. Virginia loved any kind of outdoor activities, and she was in her element in Smyrna. The city was situated at the head of a long, narrow gulf dotted with ships and yachts. Fishing and hunting were readily available to anyone willing to devote a few hours of leisure time.

Virginia had arrived in Turkey in April 1933. Her job at the consulate gave her the opportunity to brush shoulders with Turkish diplomats and statesmen. Although the post had no great importance other than for goodwill purposes in view of the political and business calm of the time, Americans had heavily invested in business and education in Turkey. If anything was to disrupt this element of calm, the consulate would be extremely active helping to protect those interests.

Smyrna was in remarkable contrast to the atmosphere Virginia had left in the United States. The Great Depression was raging and had been the topic of the newly elected president’s inaugural address the month before her departure. Virginia had listened on the radio, along with some sixty million other Americans, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt spoke to the rain-soaked crowd at the Capitol.

So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory.

They had been grim days. One of every four American workers was unemployed, thirteen million in all, and almost every bank was closed. And since the United States had never before faced such a disaster, there were no federal programs to address the needs of the populace.

Roosevelt intrigued Virginia. He had been raised in a world of privilege and wealth, with the patina and optimism of his class. It was a world not unlike the one Edwin Hall had provided for his family. Yet Roosevelt was able to sympathize with the downtrodden and meant to put the full force of his executive powers into smashing their economic despair. He gave Virginia the impression that he would be a man of action, something his predecessor, Herbert Hoover, had not been.

Nor was Roosevelt a stranger to suffering, though of a different kind from what now gripped the United States. And it was this fact that most fascinated Virginia about the man. In the summer of 1921, at the age of thirty-nine, Franklin Roosevelt had been stricken with poliomyelitis. Polio had left him partially paralyzed, able to stand only with the aid of heavy metal braces locked around his legs. Virginia found his indomitable courage remarkable; he refused to be held back by his disability. Rather, he was intent upon carrying on his life and achieving his goals.

But the American economy was a world away in Virginia’s thoughts on this particular day in December. She and the four other members of her hunting party were going after snipe in a bog about fifteen miles from the city. The group consisted of two fellow consulate workers, Maria and Todd; Todd’s wife, Elaine; and Murat, a Turkish man from Virginia’s neighborhood. The five met at Todd and Elaine’s house around noon, each bringing a contribution for their picnic lunch. The day had been carefully planned. Snipe are more prevalent during the late afternoon hours, so the party had decided to begin their excursion with lunch and then hike through the wet meadow in the afternoon in search of their prey. In truth, their camaraderie was far more important than whether they actually shot any birds.

Their mood was lighthearted all the way into the country. They had their picnic and packed the remains in the trunk of Todd’s car, then donned their hunting clothes and took their firearms out of cases. Virginia was using her favorite gun, a twelve-gauge shotgun that had once been part of her father’s collection. Todd complimented her on it.

At this point, Maria begged Virginia to tell the others about her family. The Halls, Maria exaggerated, were practically the most fascinating clan on America’s entire eastern seaboard. Virginia didn’t think her family history was that spellbinding, but the group pleaded and Virginia obliged with tales of her legendary grandfather, Captain John Wesley Hall. At the age of nine, Hall had stowed away on one of his father’s clipper ships. After a multi-year adventure at sea, he had saved enough money to buy his own ship and ultimately became very successful in the shipping industry and as an importer of Chinese goods.

Her father, taking a lesson from his own father, had built a successful business in real estate and movie houses. Virginia and her friends went to any movie they wanted to, absolutely free. She told her friends that although he had died very suddenly two years earlier and she missed him very much, she and her brother and mother still laughed about all the good times they’d had.

Virginia paused in her storytelling when they came to a wire fence, obviously constructed years before, as its condition now would neither keep anything in or out. One by one, Todd, Elaine, and Maria made their way over the fence until only Virginia and Murat were left. Virginia tucked her shotgun under her arm, leaving her hands free to negotiate the relatively slack top wire of the fence.

She would relive the next ten seconds many times in the coming months. As she lifted her right leg to climb over the fence, her left foot skidded slightly in the damp earth. The gun slipped from under her arm, its trigger catching on a fold of her hunting coat. The sound of her shotgun discharging started flocks of birds from the nearby trees. But no one in the hunting party noticed the feathered flurry. They were fixed in horror on Virginia’s mangled left foot, her blood staining the tawny field grass beneath where she lay.

The ensuing ten minutes seemed to Virginia as though she were not part of the drama, but rather watching the scene unfold before her. She was quite certain she was conscious—and was later able to describe her friends’ actions, though their voices sounded to her as if someone had turned down the volume control on a radio. She wasn’t really in pain at that point, rather her body felt wooden.

Maria, Todd, Elaine, and Murat had not had any formal first-aid training, but their quick actions most probably saved Virginia’s life. They determined that a tourniquet was needed to halt the bleeding, so they tore off articles of their clothing to make one. They made a pillow for her head out of someone’s hunting vest and covered her with a coat when she had begun to tremble from shock. A discussion ensued among them on the best way to get her to the car. In the end, they fashioned a stretcher with the remaining hunting coats and their now unloaded guns to carry her. Virginia was aware of arriving at the car before everything faded to black.

Amputation of limbs was a form of surgery that had been performed routinely on the battlefields of World War I. With no means for reconstruction and only sulfa drugs available as an antibiotic (penicillin was not put into general use until 1941), amputation was frequently a doctor’s only choice to save his patient. Military medical books at the time state that although immediate amputation is not indicated in traumas caused by bullets, it is certainly necessary in cases of confirmed gangrene. It is also necessary when a limb is completely smashed or torn off by a large projectile or fragment. Virginia’s injuries included both of these dim scenarios.

Because of the gun’s proximity to her body, the shotgun pellets destroyed Virginia’s foot. It caused extensive soft-tissue and bone damage. In addition, the wound had been badly contaminated by environmental material— fragments from her boot, the grass she fell on, the clothing her friends had used to cover her. By the time the very shaken group arrived at the hospital in Smyrna, more than an hour had passed since the accident, and infection had already begun to set in.

Although the utmost was done to treat Virginia’s wound, there was no way to adequately manage the infection. Evidence of gangrene appeared and Dr. Lorrin Shepard, head of the Istanbul American Hospital, was rushed to Smyrna. He determined that a BK amputation, the removal of her leg below the knee, was the only course of action possible to save Virginia’s life. As she was unconscious, Dr. Shepard was unable to discuss the situation with her. Nor was he willing to risk waiting for her to come to.

Even before word of the accident had reached her mother in Baltimore, Virginia Hall was being taken into the hospital’s surgical ward, where her life would be changed forever. The surgeons waiting there would have been astounded had they known the patient lying before them would soon play an integral part in the greatest war the world has ever known.

![]()

2

First Steps

Virginia floated in and out of consciousness following her surgery. During her conscious moments, which early on were accompanied by nausea from the ether she’d been given during the amputation, she attempted to recreate the events that had brought her to the hospital. She remembered the hunting expedition and the fact that she’d been injured, but nearly everything after leaving the field was a blur. During a brief segment of consciousness she had asked about her leg and was told that it had been amputated as a result of the injury.

However, thinking about the drastic life changes that would now occur was not what consumed the hours. It was her torturous pain, a red-hot burning that spread from her left hip to the tips of her now absent left toes. A different position in the bed might have alleviated the torment, but her body was so weakened from the surgery she was unable to gather the strength to move. Dr. Shepard was attempting to manage Virginia’s pain with a steady dose of morphine and this brought another complication: the vivid dreams and delusions common to those on the powerful drug. The combination of excruciating agony and morphine-induced hallucinations even led Virginia to absurd thoughts of freedom from the misery through death.

From behind her mental haze, Virginia was completely unaware of the outstanding care she was receiving. Dr. Shepard and two American nurses watched her closely the first twenty-four hours to be sure that there was no more evidence of gangrene. Additional infection would mean further surgery and an above-the-knee amputation, which would leave a far less desirable result. The shorter leg stump would be more difficult to fit with a workable prosthesis.

On the second night after surgery, a most unusual event unfolded in Virginia’s hospital room. She lay alone in a semiconscious state, when she had the sense that someone had approached the side of her bed. Standing there was her father, Edwin Hall. Virginia was flabbergasted. Her father had died in Baltimore two years earlier. She had watched the coffin containing his body being lowered into the ground. Yet there he was, smiling down at her, wearing a dapper gray business suit just as he had done almost every day of his life.

The next thing Virginia was aware of was her father lifting her out of the hospital bed. She floated in his arms to a nearby chair where they sat down together, with her on his lap as if she were a small child.

“I know you’re in a great deal of pain, Dindy,” Edwin Hall said. The nickname brought a faint smile to Virginia’s lips. When she was born, her brother, John, two years older, had been unable to say Virginia. The closest he could come was “Dindy” and the name had stuck.

“And I know that it seems as though your pain is endless,” her father continued, rocking her gently as he spoke. “Can you be strong, Dindy? Your mother needs you very much. She’s terribly upset by the news of your accident. If you don’t survive, dear little Dindy, she’ll be heartbroken.

“But if, Dindy, it’s more than you can bear, I’ll return for you tomorrow night to take you away from the pain.”

Virginia felt herself floating in her father’s arms again back to her bed. She remembered nothing else from that night, neither seeing nor hearing anything more until the next morning when the nurses rustling around her room woke her. Through parched lips, she asked them about her visitor the previous night.

“Why, my dear,” the older of the two nurses told her, “there was no one here. No visitors are allowed after hours.”

But the memory of her father’s visit was powerfully vivid. The man had looked like Edwin Hall and had sounded like him. He had even smelled like the elder Hall, a mixture of pipe smoke and bay rum. Virginia would swear the rest of her life that he had been with her that night.

For the moment she let the subject drop. But from that point on, Virginia’s recovery would proceed at an amazing velocity. Her father had asked her to fight and that was exactly what she intended to do. Marshaling the same kind of resolute spirit he and her grandfather had been known for, she became determined to survive and to live as normal a life as anyone else. After all, President Roosevelt had overcome his handicap; there was no reason why she couldn’t do the same. And her dream of a Foreign Service career would merely be delayed.

As the days passed and Virginia’s strength grew, she had time to reflect on her life thus far. Her fascination with the world had begun at an early age. She made her first trip to Europe in 1909 at the age of three. It was a time when it was not unusual for wealthy families, like the Halls, to take an extended holiday to see the world’s sights. They traveled by ship in elegant staterooms, ate fine foods, and celebrated the good life at sea. Once in Europe, the same privileged lifestyle prev...